A Brief History of Construction Startups

Note: This post is an excerpt from a larger report being created by Kabri Construction Research. Thanks to ADL Ventures for contributing some of their construction startup data.

Over the last 20 years, software and technology startups have become increasingly important and influential (of the 10 most profitable companies on the Fortune 500, 3 are internet startups, with 5 others from earlier tech startup eras.) But it’s unclear to what extent this trend is occurring in construction. On the one hand, stories of construction startups securing huge rounds of venture capital seem to be more and more common. On the other hand, we still hear about how little the construction industry has adopted technology compared to other industries. So let’s take a look at how the construction startup landscape has evolved over the past 20 years.

We’ll do this using a database we compiled of over 300 construction startups, going back to the year 2000 (and in some cases even earlier), containing a variety of information including founding date, dates and sizes of funding rounds, investors, and type of startup.

By “construction startups”, we mean any startup primarily relating to the construction and operation of buildings and infrastructure. It does NOT include real estate startups (such as Zillow or Opendoor), and it does NOT include most smart home startups, or things that would generally be considered an appliance. The rubric used was “if you would consider taking it with you when you move, it’s not included” - so smart thermostat companies (such as Nest) were not included, but smart electric panel companies (such as Span.io) were.

The dataset has a few limitations. For one, it’s limited by information that’s publically available (via press releases, news articles or other sources), and will thus miss certain data relating to funding and investors - as an example, the money to develop Construction Robotic’s bricklaying robot was sourced privately and thus isn’t included (though Construction Robotics is in the database.) Another example is that Katerra’s publicly announced fundraising (~$1.6B) is less than what it actually raised (over $2B) [0]. This will also miss most grant funding, and most very early stage companies (though it does include all of YCombinator’s construction related startups.) So it will somewhat under-estimate both the number of construction startups and the amount of money they’ve collectively raised [1]. It’s also mostly limited to information available in English, so it encompasses most US and European startups, as well as large foreign ones funded by US VCs (such as Tul and Infra.Market), but misses most Southeast Asian ones.

In some cases, a judgment wall was required if a startup was “a construction startup” or not. Many startups have products that are used by construction companies, which doesn’t necessarily make them a construction startup. In some cases this was an easy determination - companies like Expensify (which make expense report software) are often used in construction, but are obviously not construction startups. In other cases this was more difficult - many drone startups or workforce training startups, for instance, focus on a few different industries, one of which is construction, requiring a judgment call whether they should “count” or not.

Those caveats out of the way, this dataset likely covers the vast majority of startups that have raised significant funding (more than $5 million) outside of China, and thus provides an accurate picture of the construction startup landscape from a fundraising perspective. So let's take a look and see what we find.

High level view

We’ll start with a high level view. Here’s funding raised by construction startups by year:

Construction startups do seem to be taking off in popularity, having raised over $5 billion in 2021, up from under $0.1 billion in 2011. And the industry is on track to raise close to $9 billion in 2022 (based on how much construction startups have raised so far this year.)

We also see this if we look at fraction of total venture capital raised - construction startup funding is a larger and larger fraction of total venture capital invested:

But total amount of money can be misleading - this may indicate just a small number of startups receiving increasingly huge raises, with little traction outside of those. So let’s narrow our view to just looking at series A raises:

Increasing number, and increasing size of raises over time. Interestingly, the financial crisis’s impact on the construction industry is very visible here, with almost no series As between 2008 and 2012.

And we see something similar if we look at founding dates - more and more construction startups are being started every year:

One thing to consider is whether this is an artifact of information being increasingly digitized and online, rather than a change in actual proportion and investment - if press releases about fundraising are easier to find now, that might show up as increased investment whether or not any more money was being raised. One way to check this is with the YCombinator company database. YCombinator is a startup accelerator founded in 2005, that funds a large number of companies (currently over 3600), and provides a detailed database with information on every company they’ve backed, letting us avoid issues of selection bias in funding announcements.

YCombinator funds companies in batches, with a winter and summer batch each year. Here’s number of YC construction startups in each batch (grouped into buckets of 2 years containing 4 batches each):

And here’s construction startups as a fraction of overall YC startups each year:

Still generally trending upward, though it’s less direct, and actually peaks in 2017.

So overall, the trend is one of construction startups becoming increasingly popular, both from startup founders and to investors. However, construction startups are still a comparatively small fraction of the VC landscape. As a comparison, since 2000 construction startups have raised just under $16 billion, which is perhaps closer to $20 billion once unreported fundraising is taken into account. But crypto and blockchain startups raised $33B in 2021 alone.

Where is construction startup funding going?

But broad measures are only so revealing. Can we get a better sense of where specifically this funding is being funneled to?

One way to do this is to group similar startups into categories, and then look at what’s going on in each category individually. When we do this for construction, we get about 12 primary categories (along with an ‘other’ category for everything else that doesn’t fit nicely):

Builders/Developers - Startups that are tackling the entire process of constructing a building, either as a builder or as a builder+developer. Many of these startups (Veev, Katerra, Blokable) use prefabricated or modular construction to try to improve the process. Others (such as Homebound), are focusing on improving the building experience with software. These startups are almost uniformly devoted towards residential construction.

Building Materials - Startups that are trying to develop new types of building materials. This includes things like low-carbon concrete, drywall alternatives, and smart glass. This category also includes what we might call ‘low level components’ - things that we might consider ‘simple parts’ rather than raw materials, such as BAMCore.

Examples: View, Carbicrete, Electrasteel

ADUs/Office Pods - A cousin of builder startups, these are companies trying to sell small backyard homes or office units.

Energy Use and Management - Startups aimed at improving building energy use. This includes companies like Redaptive and BlocPower (which finance and install energy efficiency upgrades), as well as companies like BrainBox AI (which makes software to try to optimize HVAC use.) It also includes startups like Intellihot, which make more efficient water heaters.

Examples: Redaptive, Dandelion Energy, Domatic

Marketplaces - “Uber for Construction” - Startups trying to connect the large number of buyers, sellers, and transaction parties that exist in the hugely fragmented construction industry. These range from workforce sourcing companies like Workrise, to construction equipment marketplaces like EquipmentShare, to companies that help homeowners find renovation contractors like Sweeten.

Examples: Equipmentshare, Amast, BuildZoom

Distribution and Logistics - “Amazon for Construction” - startups trying to tackle the problem of getting building materials to the jobsite.

Examples: RenoRun, Tul, Infra.Market

Construction Management Software - “JIRA for construction” - startups that make software for jobsite coordination, progress tracking, task and document management, and other similar tasks.

Robotics - “Roomba for Construction” - startups trying to find ways to introduce robots onto the jobsite, or in other parts of the construction value chain.

3D Printing - “Prusa for Construction” - a cousin of robotics startups, these are companies trying to use scaled-up 3D printing technology to fabricate entire buildings or building components.

Examples: Icon, Mighty Buildings, Branch Technology

Fintech - “Stripe for Construction” - companies trying to improve the financial plumbing that the construction process uses.

Examples: Built Technologies, Rigor.build, Levelset

Datacapture and Digital Twins - Companies using some combination of drones, 360 degree cameras, hardhat mounted cameras, and other sensors to record and analyze jobsite data and track construction progress. Often utilize computer vision and machine learning techniques to process this data.

Examples: OpenSpace.AI, Doxel.AI, Versatile

Renovation/Repair/Maintenance - Companies trying to improve the process of maintaining a building. These range from software companies who offer maintenance subscriptions, to products that can monitor and report water usage and leaks, to companies that make bathroom renovation easier.

Examples: Humming Homes, Block Renovation, Made Renovation

Other - Everything else that doesn’t fit into one of the above categories. This includes AR/VR startups, companies that make AEC design tools, companies that make software to streamline one particular workflow (what we might call “excel replacements”), construction insurance companies, and anything else that doesn’t fit into one of the above.

This isn’t a perfect categorization - in a few cases (like repair/maintenance, and energy management) it lumps together companies which are actually fairly different. And there are plenty of companies which are difficult to categorize, or could fall into multiple categories (is Icon a 3D printing company or a builder/developer? Is Infra.Market a distribution company or a marketplace?) But overall I feel it does a fairly good job of carving things at the joints.

Let’s first look at the relative sizes of these categories. Here’s these categories broken down by total amount invested in each:

We see builders/developers is the largest category, with close to $3.5 billion invested. I’m not sure if this should be surprising or not - residential construction is a huge, highly fragmented, and inefficient industry, which seems like an extremely ripe target for startup disruption. But scaling these efforts is brutally difficult (especially if you do your building in-house, and especially if you’re trying to see venture-level returns), and this category has seen quite a few company implosions large and small.

The next largest is marketplace startups, at $2.7 billion invested. This seems like an obvious place where construction startups can be successful. The local nature of construction means that there’s lots of stakeholders; the project nature of it means there’s lots of transactions; the high cost and risk means there’s lots of value in establishing trust; the variability means that there’s lots of valuable assets that are often sitting idle. All of this makes it ripe for various marketplace startups to streamline.

After this is building materials, at $2.6 billion invested. The majority of this ($2 billion) has gone into smart glass/smart window startups, with almost all the money ($1.7 billion) going to a single company, View, which doesn’t seem to be doing well (current market cap is just $523 million.) Other than smart windows, most of the investment here is going towards various “green” building materials - low carbon concretes and steels, etc.

Those 3 categories make up more than 50% of construction startup investment, with the rest sharing smaller slices of just a few percent each. The relative sizes of some of these segments was surprising to me. I was more or less completely unaware that the smart window segment had attracted so much investment (I’ll have to walk back some of my previous comments about the lack of innovation in smart glass, since it seems like folks are trying.) On the other hand, based on the volume of the YIMBY discourse, the ever-present enthusiasm for tiny homes, and the number of startups I was aware of, I expected the ADU segment to be a lot larger [2]. And AR/VR, which seems like an obviously high potential technology for construction, has seen much less VC investment than I expected (perhaps everyone is still gunshy about the previous AR bubble, with products like Magic Leap and Google Glass that failed to pan out.)

I was also surprised at how much investment hardware companies received - total investment is roughly 50/50 between hardware and software companies (though software companies outnumber hardware companies about 2 to 1.) I expected more money to have flowed into software companies, which have better economics, are more straightforward to scale, and a lot of “startup infrastructure” already exists for them (or so I thought, at least.)

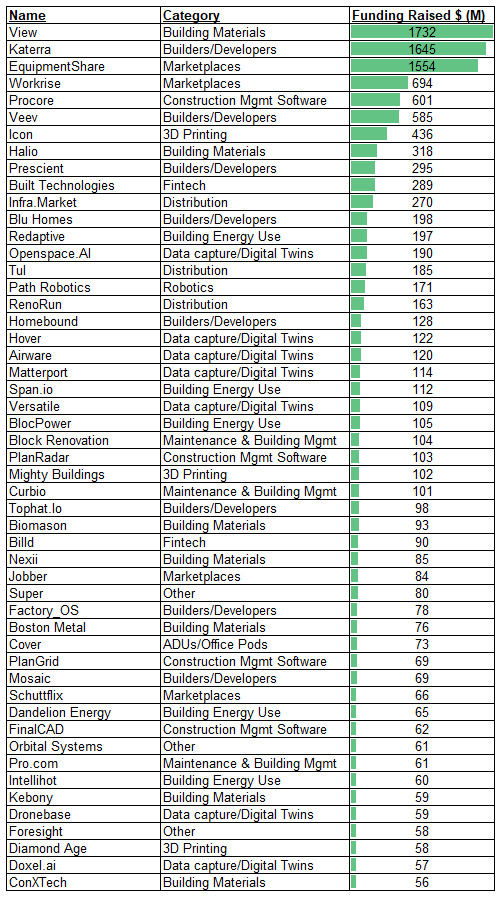

Like with the categories themselves, this investment gets distributed in an extremely asymmetric way. Here’s the top 50 construction startups by total funding received:

The top 5 companies (View, Katerra, EquipmentShare, Workrise, and Procore) have received nearly 40% of the total funding in the entire sector, and the top 20 companies have received more than 60% of the total funding. Startup returns are asymmetric, and it seems like this applies to funding as well - the most promising-appearing startups get disproportionately large shares of investment.

This is, frankly, a somewhat brutal chart. A substantial number of these top companies are either high-profile failures (Katerra, Blu, Airware) or are in fairly rough shape (View, Tophat). The biggest success here so far is probably Procore, which is nonetheless pretty far from seeing the sorts of returns that the biggest tech startups in other sectors have seen. Most VC returns come from a small number of huge successes that end up being worth 10s or 100s of billions (for instance, 65% of the value of YCombinator startups comes from just 5 companies), but construction has yet to see any $10 billion+ startups. Part of this is possibly due to a sort of natural throttling (caused by, among other things, rational risk aversion) that limits how fast even a software company with strong network effects can grow in construction. For instance, at its IPO, Procore estimated that it had captured just 2% of its potential market despite being around for over 15 years and having a category-defining product.

Categories over time

We can get an even better look if we look at category funding over time The below graphs show the funding each category of startup has received each year. The black squares indicate funding received by the largest company (as measured by total funding received) in that category (click to embiggen):

(note: all graphs use the same scales)

This really gives a clear view of the spikiness of startup funding. The top 3 categories (Marketplaces, Builders/Developers, and Building Materials) account for more than 50% of construction startup funding. Within each category, a single company (Equipmentshare, Katerra, and View respectively) account for ~50-60% of the total funding raised.

The same is true for other categories. Funding for 3D Printing has almost entirely been allocated to Icon (~70% of the total), funding for Fintech has largely gone to Built Technologies (~43% of the total), funding for Construction Management Software has mostly gone to Procore (~47% of the total.) Trends in construction startup funding volume are closely tied to the fortunes of just one or two companies.

Two categories where this isn’t the case are Energy Management and Datacapture startups, where the largest companies have received just 25% and 17% of the total category funding (Redaptive and OpenSpace.AI, respectively). For the former, this is perhaps because this is a bit of a “grab bag” category that’s lumping different businesses in different markets together [3]. For the latter, it suggests to me a combination of the technology/market being in early stages, and a category leader not having yet emerged.

With these graphs, we can paint a stylized picture of how the construction startup space has developed. Though there’s a few outliers (Procore, View, and a few builder startups like Project Frog), the sector really starts going around 2012 - the construction market was finally on an upswing following the financial crisis, smartphones and tablets had reached significant market penetration allowing new jobsite capabilities, and VC funding was on the rise. Procore, View, and Katerra start to steadily receive investment, along with the first fintech, marketplace, and datacapture startups (the latter category helped along by steadily improving drone technology.) Investment in construction management software, having been anemic for years, starts to pick up, a trend which continues today.

As time goes on, a few other trends start to kick off. The passage of California’s SB-1069 in 2016 which allows for backyard ADUs starts a trickle of ADU startups (of the 14 ADU startups in this dataset, 11 were founded in 2016 or later, and 11 were founded in California), though this space remains comparatively small. Advances in computer vision and machine learning (what I’ve heard referred to as “the peace dividend of the self-driving car wars”) shows up as a trickle of investment in robotics startups, as well as increasing investment in datacapture startups. Robotics remains fairly niche, however - the biggest spike here is from Path Robotics, a company which only barely made the cut to count as a construction startup (they make robotic welding equipment, and mostly seem to be focused on manufacturing, though they apparently have plans for construction.)

This is also when Softbank’s massive investments start to distort the landscape, culminating in investing over a billion dollars in Katerra and View in 2018 (this is also around the time they were pouring money into WeWork.) Coincidently, this is about when you start to see news articles about construction startups poised to disrupt the construction industry.

Both Katerra and View would ultimately be high-profile flameouts. But it doesn’t seem to have had much of a chilling effect on the construction startup space. Both of their categories continue to receive significant investment (in the former, companies like Veev and Prescient have received several hundred million in funding; in the latter, we’re starting to see increased enthusiasm for low carbon building materials such as concrete and steel.) And companies in other categories are starting to receive large valuations - Openspace (datacapture), RenoRun and Infra.Market (distribution), Built Technologies (fintech), and EquipmentShare (marketplaces) have all received $100 million+ investment rounds, with EquipmentShare also securing a $1.2 billion line of credit (suggesting fairly reliable cashflow.)

One thing this data makes clear is that a lot of efforts at construction innovation aren’t taking place in the startup ecosystem. Many, perhaps most, innovative building products don’t seem to come out of startups - they’re either small-scale developments by businesses that don’t obtain VC (such as EasyFrame, Facit Homes, or 3-in-1 Roof Tiles, products from large, established construction suppliers (such as LP’s Smart Siding), or from academica (such as much of the work that has gone into attempts at construction robotics.)

Who is funding these startups?

Where is this startup funding coming from? Though we don’t have access to sizes of investments, we can look at other measures. Here’s the top 50 VC funds by number of construction startups they’ve backed:

(note: this list excludes YCombinator)

Brick & Mortar Ventures is a huge outlier, having funded more than twice as many construction startups as the next highest number. After this, we see plenty of other building or proptech focused VCs (MetaProp, Builders VC, Cemex Ventures, Blackhorn), as well as some other fairly prominent names (a16z, Google Ventures, Founders Fund, Khosla, Tiger Global.) But the overall pattern here is a large number of investors VCs backing just a small number of construction startups - overall we tracked more than 800 sources of funding for construction startups (more than twice as many sources of funding as there are startups), the majority of which (700+) backed just one company.

Conclusion

Like the rest of the startup world, the construction startup space is driven by a small number of outliers - just a few companies have taken the majority of the investment in the sector, an asymmetry that gets even sharper if you look at individual categories.

Overall it appears that we’re still in the early stages of construction startups. The sector doesn’t really start to see traction until 2012, and a large amount of investment previously went to physical product companies that failed to pan out. But we’re now starting to see large investments in the sorts of startups that are applying a successful startup playbook to the construction industry, in the form of large marketplaces, computer vision, Amazon-esque distribution networks, and financial infrastructure.

However, it’s likely that the nature of the construction industry means these companies may have a harder time scaling than similar companies have elsewhere. Procore is an illustrative example - it’s had many years (18) to gain traction, and has received a huge amount of investment (over $600M, by far the most in the construction management software space.) It’s used this time and funding to become the category leader in its space. It solves a pressing problem via software (avoiding the large marginal costs of hardware), and has an extremely powerful flywheel available to it (the way the product works means that any customer might invite hundreds of other potential customers), as well as an elegant mechanism (an app store) for adding more functionality, decreasing churn, and upselling customers over time. In short, Procore has a huge number of advantages, and in some ways is a ‘best case scenario’ for a construction startup.

But Procore hasn’t seen the same sort of success that startups in other spaces have - it’s market cap is less than $10B (it’s currently trading below its IPO price), it’s spending more than 70% of its revenue on customer acquisition, and it’s not expected to be profitable in the immediate future. Even companies with every possible advantage have a tough time in the construction industry.

These posts will always remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work and also gain access to a members-only slack channel.

Construction Physics is produced in partnership with the Institute for Progress, a Washington, DC-based think tank. You can learn more about their work by visiting their website.

You can also contact me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or by email: briancpotter@gmail.com

[0] - This can be confirmed from their bankruptcy documents.

[1] - Another limitation is that in the interests of simplicity, funding information was in some cases compressed. Multiple rounds in a single year might be counted as a single round, for instance. And though it tracks investors, it does not track which round they invested in. It also does not distinguish between debt and equity fundraising.

[2] - One caveat to this is that I suspect the dataset is missing some large funding sources. For instance, I wasn’t able to find public funding information for Boxabl, but anecdotally I’ve heard they’ve raised in the neighborhood of $75 million, which would increase the size of this category by quite a bit.

[3] - Though arguably they’re not THAT different - in a sense, they’re all selling the same product (lower building energy use).

Super interesting. Interesting to me that there wasn't any startup funding in the early 2000's boom, prior to the recession. This actually gives me some hope that the new funding is a real shift in potential.

But compared to crypto, it is still frustratingly low. I agree the ADU numbers seem small. (FYI I have seen Boxabl founders tweet that they raised $60 mil. And they just started accepting non-accredited investors.)

This was interesting, and I can appreciate the challenge associated with defining some of these categories. Reading through some of the service descriptions I'm getting memories of the late 90's dot-com craze. My sense is that there isn't much room for disruption on the bricks & mortar front because industry incumbents operate on tight margins already. Software firms probably have the most opportunity because of low overhead and the possibility of getting subscription revenue from construction and A/E firms for a long time---provided their products are effective.