Bricks and the Industrial Revolution

Brick has a long history of use as a building material - in one form or another, it’s been in use for thousands of years. And though today brick is mostly used as a high end architectural finish (thanks to those thousands of years of history, people have grown attached to the aesthetics of it), up until the mid-20th century it was the standard material for constructing a building. Industrialized countries made billions of bricks every year to build everything from houses, to factories, to office buildings.

Britain especially became a huge consumer of brick. Though it had been in use since the Romans, after the Great Fire in 1666, brick became the default building material in Britain, helped along by new London building laws that only allowed brick or stone construction. Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, bricks (like so much else during the industrial revolution) gradually changed from hand-made, crafted items to mass-produced, factory-made objects. Because its use as a building material spans from a pre-industrial era through to the present day, brick production in Britain is an interesting case study in building material innovation, and industrialized construction.

Brick production in early 1800s Britain

At the beginning of the 1800s, though brick was a popular building material, brick production was a small scale, craft based process. Bricks were heavy and transporting them was difficult, so most bricks were produced locally within a few miles of where they would ultimately be used. Clay surface deposits were abundant, and a brickfield could be established with relatively little investment or equipment. The result was that brickmaking was done at hundreds of small brickfields around the country, each one employing a small number of workers (perhaps 5 or 6 on average).

Traditional brick making was highly seasonal work. Clay would be dug out of the ground in the winter months, then left to break down and become more easily worked. When ready for production, the clay would often be mixed in a pug mill, a 1700s invention that allowed the mixing of clay with other elements and allowed the use of what might otherwise be inferior clay. After the risk of frost had passed, the clay would have water added to it and then placed in brick molds, after which it was taken out and left to dry in the open air for several weeks (this prevented the wet bricks from cracking during the firing process). Once dry, the bricks would be fired in a kiln, or in open air kilns called clamps. This process was slow and laborious, and because all the work took place outside, the bricks were at constant risk of being damaged by the elements.

Typically, the actual production of bricks was subcontracted work. The owner of the brickfield would hire a molder, and pay a certain rate per thousand bricks (a method of pricing still used today). The molder would then hire the rest of the crew depending on how many bricks needed to be produced. The seasonal nature of the work meant that brickmaking was often part-time work done by workers in other trades, and brickmasters might bring their wives and children on as temporary staff if the work required it. With traditional methods, a brick field might produce 20,000 to 40,000 bricks a week. The difficulty of transporting them (moving bricks even a few miles might add 50% to their cost) meant that brick production was highly dependent on local needs, and demand was highly variable. Because they required such little investment, it was common for brickfields to be started specifically for local building projects, and then closed when no longer needed.

Early mechanization in brickmaking

Britain in the 1800s saw an explosion of invention across all fields, and brickmaking was no exception. A population explosion (the population of England and Wales doubled between 1800 and 1851), along with increased construction of railroads, canals, and other civil infrastructure greatly increased the demand for bricks, and substantial effort was expended on developing machines to increase brick production.

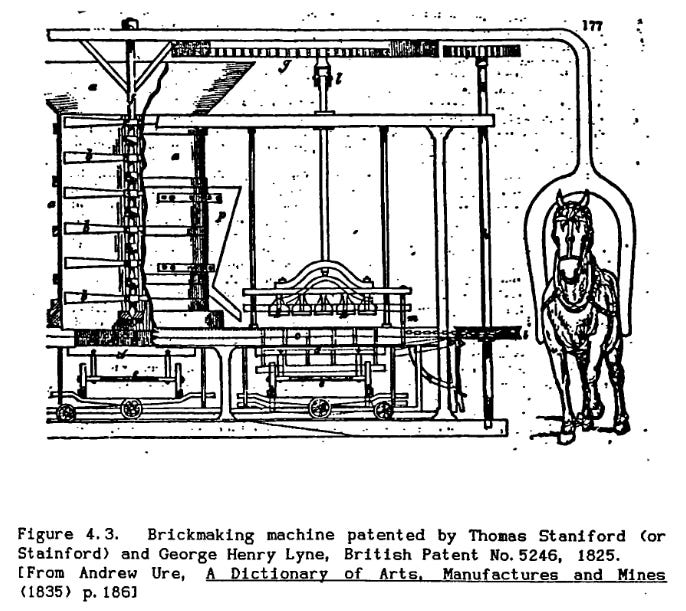

Most early brick-making machinery development was focused on the process of molding the bricks, the task considered to be the most difficult and require the most skill. Inventors came up with a variety of mechanical arrangements for placing wet clay into the molds, from horizontal or vertically mounted wheels, to chain-driven molds that oscillated back and forth, to mechanical screws, pistons, and rollers. These machines were generally unsuccessful - they had great difficulty placing the clay into molds hard enough to expel all the air and make a properly formed brick, but lightly enough that the clay wouldn’t stick to the machine (similar problems would plague the mechanical brick-laying machines that would be developed over a century later). And the actions of the machine would often distort the wet bricks when they were extracted from the machine or being moved (by contrast, hand molders learned to make bricks in a slightly misshapen fashion so they would settle into the proper shape). By the 1850s, molding machines could sometimes be found at brickfields, but many technical issues hadn’t been solved, and they were of limited success.

In addition to molding machines, there were also efforts to mechanize the production of exterior-facing pressed brick. These bricks required smooth, blemish-free surfaces, and were traditionally made by beating a partially dried brick with an iron wedge, or by polishing it on an iron plate. In the early 1800s pressing machines were developed that could apply a large amount of force to a partially dried brick, resulting in hard, smooth faces. Unlike molding machines, which were complex, expensive, and required substantial changes to the brickmaking process, pressing machines were much simpler, and were easily adopted by existing brickfields. They also had the advantage of operating on partially dried brick, instead of the more difficult to handle wet clay. By the 1850s, pressing machines were common, though the process of making pressed bricks remained labor intensive.

Britain’s brick tax

One factor that hampered the progress of brick-making innovations in the early 1800s was the tax on brick production. To pay off Revolutionary War debt, the crown instituted an excise tax on bricks in 1784. All brick makers had to register with the excise officer, and leave drying bricks outside in a manner that could easily be counted (the tax was levied per 1000 bricks). To account for breakage and damage after counting, the tax was based on 90% of the number of bricks counted.

The brick tax restricted innovation in brick making machinery in several ways. For one, it raised the cost of using bricks. For another, the assumed rate of damage (10%) disincentivized experimenting with new methods or machines for brick production. If an experimental brick machine produced large numbers of unusable bricks beyond what the tax assumed (likely with new and experimental technology), the brickmaker would still be taxed on them. One unlucky brickmaker with an experimental machine in 1839 was forced to pay taxes on 270,000 unusable bricks during its first two years of operations, out of a total of 1.4 million produced.

The requirement for allowing the tax collector to inspect the bricks during drying also implicitly assumed the manufacturing process required drying, and thus accidently disallowed any other type of production. Alternative methods that didn’t require a drying period, such as the dry-clay process which used clay without added water, thus had difficulty gaining traction.

The repeal of the brick tax in 1850 made experimenting with brick manufacturing much more feasible, and is part of the reason for an uptick in brick machine patents during the second half of the 19th century.

Extrusion machines and other developments

By the 1850s, brick making machines had had some limited success, but hadn’t yet been widely adopted in Britain. True mechanized brick production would have to wait for the development of extrusion machines.

Extrusion-based machines were first patented in the 1810s. Unlike molding machines, extrusion machines forced a column of clay through a specially shaped tube, which was then cut with a moving wire. Like the molding machines, extrusion machines initially had difficulty with manipulating soft, wet clay, and they saw limited adoption. Getting them to the point of usability would require a detour through a neighboring industry.

While some inventors were trying to solve the problem of getting a machine to make bricks, others were working on a slightly different problem in clay manufacturing - how to make hollow tubes and tiles. The impetus for this was the need for agricultural drainage - undrained clay soils were poor for growing crops, and in the early 1800s many clay-soil farms across Britain lay abandoned. To incentivize draining the land and reclaiming it for agricultural use, the crown passed several acts providing funds for permanent drainage improvements of farmland. Incentive was also provided by the Royal Agricultural Society of England, which (along with other, local societies) held frequent contests and awarded prizes to the makers of useful agricultural machinery.

Of the different methods for draining farmland, it was found that a shallow trench with clay pipes or tiles running along the bottom performed especially well. Traditionally, tiles and pipes for drainage had been made using the same molding process as bricks, often in the same brickyards. The process was expensive, and the tiles were out of reach for most farmers.

Initially, attempted mechanization of tile-making was done by adapting the molding machines used for bricks. Spurred on by the various incentives (especially the agricultural society’s contests and prizes), inventors gradually refined and iterated on the most successful designs, which proved to be the machines that used an extrusion-based process. Over the course of the 1830s and 1840s, extrusion-based machines for making tiles would be greatly refined - by the end of the 1840s, tile-making machines were capable of making up to 20,000 tiles a day.

These developments coincided with the repeal of the brick tax in 1850, spurred a great deal of innovation in brick making machines. The successful extrusion-based tile machines were adapted to make bricks, and gradually improved. Today, bricks are still made using a wire-cut extrusion process.

Along with extrusion-based machines, a series of other developments over the 19th century gradually improved the brickmaking process:

The dry-process, which involved pressing a special clay mix that did not require adding water, was eventually perfected. This would most famously be used with Fletton bricks, which were made with a special clay that not only didn’t require water, but naturally contained fuel oil (making them cheaper to fire).

Hoffman Kilns, invented in 1858 and brought to Britain in 1862, allowed bricks to be fired more efficiently.

Gradually improving transportation technology - first railroads and canals, then roads and trucks - made it increasingly feasible to transport bricks far from the production site.

The age of mass production

By the turn of the 20th century, brick-making machines could reliably make large volumes of brick, and machine-made brick was firmly established in Britain. But like any piece of construction technology, adoption remained slow, and brick production was still often done manually well into the 20th century. This video from 1923 shows a large scale but nonetheless manual brick making operation.

Part of this slow adoption was due to the highly distributed nature of brickmaking. In the 1850s there were over 1400 brickworks throughout England, which grew to over 1700 in the 1870s. And though this number would gradually shrink as small operations consolidated into larger ones, this process took time, and largely occurred in the 2nd half of the 20th century. By 1950 there were still over 1000 brickworks in England, though by 2010 this had been reduced to just 50 - a result of industry consolidation and falling demand for brick, which peaked in production in the 1960s.

But part of the slow adoption of brick making machines was that brickmaking was stubbornly resistant to increased efficiency from mechanized production.

By the late 1800s, mechanically made brick was common, but the machines hadn’t had any impact on brick prices. In 1861 one British architect commented “The high price of bricks at the present moment was an extraordinary fact...the duty had been taken off and now good stocks were much more expensive than when the duty was on.” As late as 1885, the price of machine-made bricks were reported to cost just over 17 shillings per thousand, while hand-made bricks were just over 19 shillings - not significantly different, and not much less than when the brick taxes were in effect.

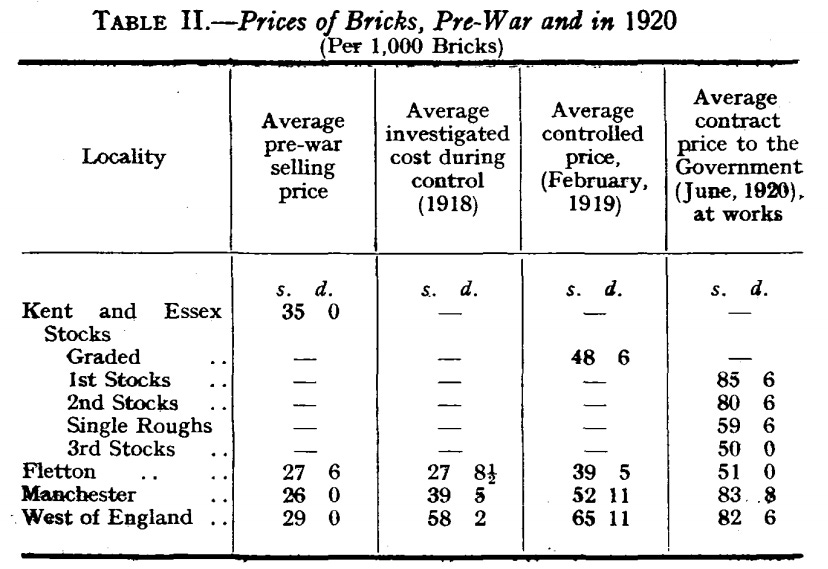

As time went on, brick making mechanization continued, but costs failed to drop. By the 1910s (just prior to WWI), brick prices ranged from 26 to 35 shillings per 1000 bricks:

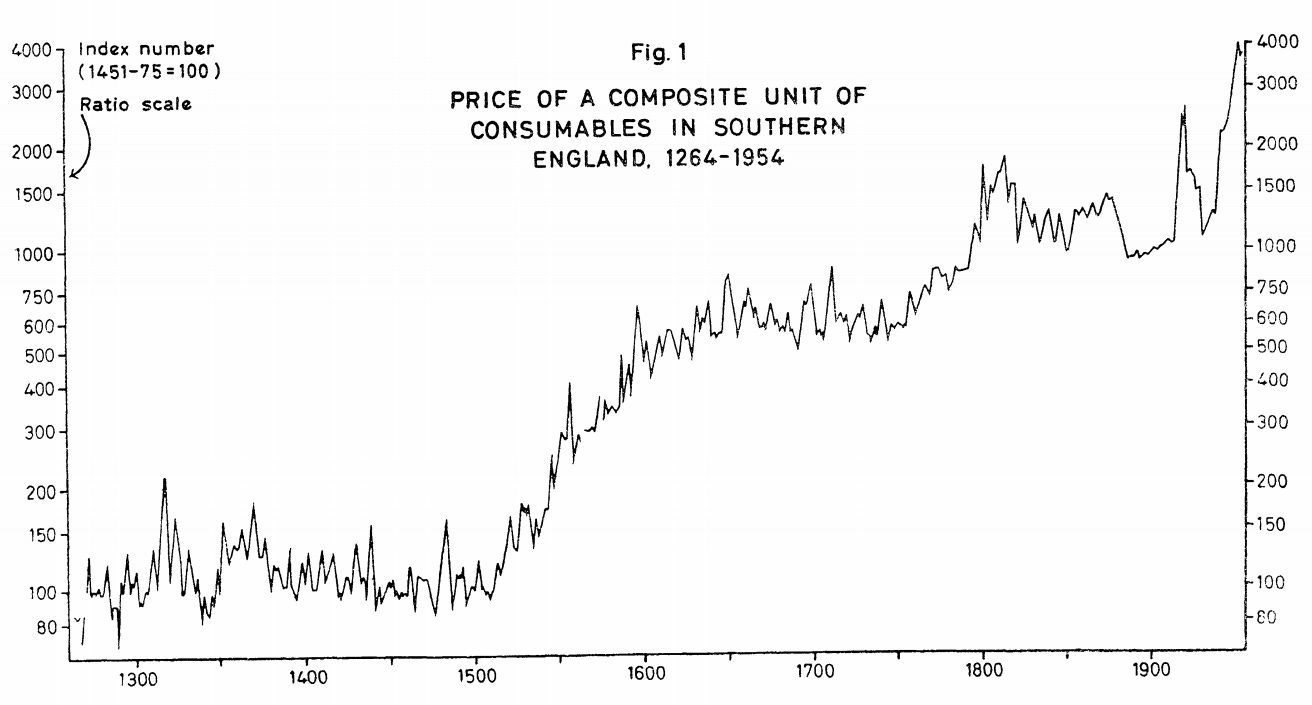

This doesn’t appear to be due to inflation - until the onset of the war we see a relatively flat price index in England over the preceding century:

And it doesn’t seem to be due to brickmakers pocketing excess profits - the industry in the early 20th century was cutthroat:

Overproduction caused the market prices to be out of balance with the cost, and many brick manufacturers were forced to go out of business, while others continued under receiverships after failure. What little prosperity there was in the trade moved in cycles, but almost invariably the losses made counterbalanced the profits made in more prosperous years. Witnesses have stated that their firms experienced very bad times between the years 1900 and 1914, and bricks were sold at almost any price to get them out of the way.

And it doesn’t seem to be unique to Britain. Turning briefly to the 20th century US, we see similar data - rather than getting cheaper, brick price has consistently outpaced inflation.

Today, brick production has been almost completely mechanized in large factories, and the industry remains low-margin and cutthroat, but brick is somehow more expensive than ever. In the US brick costs somewhere in the neighborhood of $350 to $600 per 1000, roughly 2 to 4 times as expensive as it was in 1930.

We generally expect industrialization and mass production to make things cheaper. We see this all the time, from nails to cars to fabric. However, it never managed to make bricks cheaper. Rather than bringing down costs, industrialization in brickmaking seems more like a red queen’s race - requiring more and more investment and innovation simply to stay in place, or to slow the rate of increase. Despite having factories that can make 500,000 bricks a day or more, the cost of using it means we’re forced to carefully husband it, putting it only on the sides of buildings most likely to be seen.

The puzzle of mechanization

So if it didn’t make bricks less expensive, why did brick production mechanize at all?

Part of the answer is likely that increased demand couldn’t be met by craft production alone, and without mechanization we’d see the price shoot up as various users bid up the relatively limited supply of bricks that craft production could produce.

I suspect that cost disease is part of the answer as well - manufacturing was gradually driving wages up, making craft production more and more expensive. But a spread of manufacturing capability and expertise would also lower the cost of mechanizing brickmaking (easier to build a brick factory if there’s lots of machinery suppliers around, and lots of people who know how to operate and maintain the machines you buy). And the places with a lot of manufacturing activity were also likely the places building the most, and most in need of bricks. We can imagine the process playing out piecemeal across the country, where brick production near high-wage, rapidly growing urban areas mechanizes, but production in more rural areas remains manual for longer.

Manual production could have also held on due to transportation improvements that made shipping brick farther more feasible, especially places connected by rail lines or canals. Larger shipping radii would have allowed for larger factories and a more assemblyline style process, even if it remained manual (the 1923 video of a brick factory above seems like it resembles this), though the modern geographic spread of brick factories suggests there’s limits as to how much the process can be centralized.

The logic of brick production is reminiscent of some of the issues with building prefabrication - the low product-value density of large building components makes them difficult to cost-effectively ship long distances, requiring lots of distributed production locations. The same constraint seems to apply to brick - even an island the size of England can support over 40 brick production facilities.

The dream of prefabrication was that these difficulties could be overcome once you had sufficient scale, and your factory was churning out homes by the tens of thousands. The lesson from brick production seems to indicate that industrialization and mass production isn’t enough - that moving a large amount of bulky, heavy materials around is a fundamentally expensive operation that you can’t mass produce your way out of.

Conclusion

Over the course of 150 years, brick production in Britain gradually changed from a manual, hand-made process to a mechanized, industrial process. However, unlike the industrialization of other things such as nails or fabric, industrialization doesn’t seem to have ever made bricks cheaper. This implies that industrialization alone won’t be sufficient to reduce construction costs, and that moving large volumes of heavy, bulky material has fundamental cost barriers that are difficult to overcome.

These posts will always remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work and also gain access to a members-only slack channel.

Construction Physics is produced in partnership with the Institute for Progress, a Washington, DC-based think tank. You can learn more about their work by visiting their website.

You can also contact me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or by email: briancpotter@gmail.com

I want to adress the factor of brick quality. Extruded bricks are of way higher quality and dimension in general. Back in the day regular field-burn bricks went into the walls not to be seen and a higher grade was placed on the outside. When I open a wall of mine they are all uniform (Reichsformat) but most of them look like a toddler could do them better. Today they are still graded (mostly depending on their position in the kiln) but even the lowest ones are nicer than the best field-burn bricks where. As why field-burn bricks are cheaper, a quick google search will show you.

Also a huge factor: Despite being energy intensive, bricks are often still made locally. They have imense shipment costs. Therefore the rising labor and energy cost in the last third of 20th century should also go into the equation.

I was involved in an interesting experience in cost of masonry/transport in Brazil. We were building a relatively large industrial plant in a remote location, for a multinational client. The drawings showed a block wall made from a standard module size block. All of the local block fabrication was artisanal, lacking any industrial fabrication facility. The contractor laid up a completely non-uniform wall with local block, and then parged the entire surface, and struck off faux mortar joints in an exact module dimension.to perfectly match the drawings. Apparently this was a common local practice, and the additional labor of the parging/striking was less than the cost to bring in uniform sized block...