We’ve previously looked at how construction costs compare across different locations, and different building types. But an overall cost number only tells you so much. It’s useful to dive a little further and see how that money gets spent. How much is going to the framer? How much is for the foundations? How much is for plumbing? Let’s take a look.

For data, we’ll use a few different sources. The National Association of HomeBuilders helpfully provides a breakdown of the costs for “average” new construction. This is based on survey questionnaires sent to builders, asking for their home construction costs. We’ll supplement this with data from construction estimating guides, also generated from survey data [0]. (I use the Craftsman National Construction Estimator, a sort of Great Value RSMeans).

Cost Breakdown for a New Single Family Home

The above breakdown (click to embiggen) is for the direct costs of construction. It doesn’t include things like the land cost [1], financing cost, sales and marketing, or the builder’s profit. The above is for an “average” new home, which according to NAHB is 2954 square feet, and costs $114.36 per square foot to build.

The graph is color coded - green represents overall framing cost, dark grey represents overall foundation cost, dark blue is exterior finishes, orange is building systems (HVAC, plumbing), yellow is interior finishes, light blue is “outside costs” (driveway, porches, etc.) and light grey is miscellaneous fees and expenses.

A few things jump out at us. First, there’s mostly no single large line item - nothing above 15% of the total. Construction costs are made up of many different sub-assemblies and trades, each with a modest portion of the cost.

The largest line item is framing. This is the lumber, plywood, nails, and everything else needed to build the actual structure of the house. For a single family home, this comes to just under 14% of the total construction cost.

Because it’s such a large fraction of total expense, a lot of effort has gone into developing alternative, more efficient ones. Systems like panelized light frame wood, SIPs, AAC block, and Elementhus are all attempts at a more efficient framing system. This mostly hasn’t worked - even basic panelization tends to be more costly than site-built construction (though I’ve heard costs are trending downwards), and the least expensive framing option remains the balloon frame and it’s descendents.

After framing, the next largest expense is the foundation, at just under 12% of the total cost. It’s easy to see why the foundation is a significant expense - building a foundation requires heavy equipment to excavate the site and move the soil into its final position, and pouring a large volume of concrete. Moving heavy things is expensive to do.

This is a difficult cost to reduce, as the foundation serves several different purposes. It acts as a water barrier, a level surface for constructing your building on, a system for transferring the building load into the ground. Attempts at more efficient systems have a tendency to simply shift where the costs occur. For instance, you can reduce the excavation and concrete cost by using a crawlspace foundation on piers, but this requires extra framing to act as the floor, as well as heavy transfer framing. Or you can try to use prefabricated concrete foundations, but then you need to figure out some way of getting a uniform bearing surface (often this involves site-poured grout or concrete, eliminating much of the benefit). I’m aware of very few attempts to design a more efficient or prefabricated foundation system.

After the foundation, there’s a long tail of things that make up 4-6% of cost. Plumbing, HVAC, Electrical are each ~5%. Exterior wall finish is just over 6%; builders will often try to cut down on this cost by putting expensive materials such as brick on just the front of the house. Exterior windows and doors are 4%, cabinets and countertops are 5%, flooring is 4%, drywall and interior trim is 4% each.

Many of these costs are for the basic functionality of the house, or are for particular features. But a significant fraction, 20% or so, is dedicated to things that are mostly aesthetic. These are things like interior and exterior finishes, cabinets, fixtures, etc. Because their function is aesthetic, and they engage the senses, people have very strong opinions about how they should look and feel. It’s not like the electrical system which can comfortably exist invisibly within the walls.

The charitable interpretation is that these things define how a space feels, and so in fact are a critical feature of the home. The uncharitable interpretation is that they’re a vehicle for conspicuous consumption and status signaling, a way of showing off to your neighbors and folks on the ‘gram, and that the expense is the point.

Regardless of the motivation at work, it makes it difficult to reduce costs. Despite the development of new, less expensive materials, people still prefer finishes made from hardwood, tile, brick, and stone. People are resistant to less expensive substitutes that have a different “feel”, even if the substitutes perform better:

Luxury Vinyl Plank is basically indestructible and maintenance free, but people still prefer hardwood floors.

A one-piece shower stall will be less likely to leak than a tiled shower, but people still prefer tile.

Lower cost finishes is a major reason that manufactured homes are able to achieve lower costs per square foot, and are also a reason that they’re perceived as “cheap”.

The costs above are for single family home construction. Other types of construction will vary depending on the requirements of the building:

Multifamily buildings will have a similar cost structure, but tend to have a smaller fraction dedicated towards foundation costs, as you’ll have more stories sitting on a similarly-sized foundation.

Buildings that use structural systems other than wood will see an increase in the proportion dedicated to framing. For residential construction this occurs past floor 4-5, so you’ll see a lot of apartment buildings built this height or lower.

Industrial buildings, warehouses, etc. will spend a smaller fraction on finishes, and a larger fraction on building systems such as electrical or mechanical.

Restaurants will spend a greater proportion on mechanical systems. (allegedly this is the reason that Subway, with it’s low kitchen requirements, is such a popular franchise).

Labor vs Material

Now that we’ve looked how much each different trade costs, let’s dive a little bit deeper. What’s driving the above costs? How much is parts and materials, how much is labor?

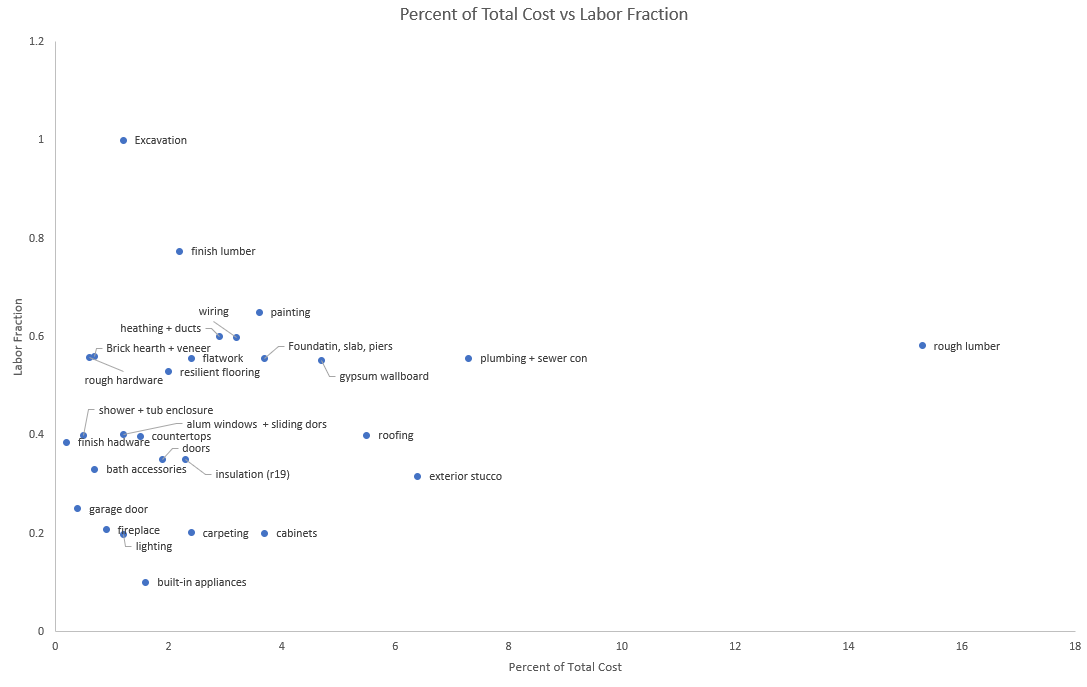

Helpfully, the national construction estimator summarizes the typical trades for a new home, and breaks them down by their parts and labor costs. Their breakdown is slightly different than NAHBs, but mostly matches up (one exception here is the foundation, where NABH estimates a much higher cost. It’s not 100% clear to me what’s driving the difference here.)

First off, we see the overall fraction of labor in construction is astonishingly high - around 50% of the direct cost. For reference, the labor fraction for car manufacturers is in the 10% range (or less). Restaurants operate at closer to 30%. A 50% labor as a fraction of the cost means construction’s cost structure is much closer to a service industry than a manufacturing industry.

However, looking at the above breakdown, we see quite a range - the items with a high degree of prefabrication have very low labor fractions. Things like appliances, cabinets, or lighting are factory-assembled items that the on-site worker just needs to install. These have a labor fraction in the 10-20% range. But things like painting, framing, or concrete work have much higher labor fractions, 60-70% or more. These are the sorts of items that are essentially built on-site out of raw materials.

Interestingly, we don’t see any relationship between percentage of overall cost and labor fraction. And we don’t see any real change if we chunk the data into high cost items and low cost items, we still see a similar labor fraction. So it’s not the case that costs are increasingly dominated by the high-labor fractions of construction (which is what I expected to see).

Another thing that jumps out is the total lack of equipment costs. For tasks that require heavy equipment (excavation, concrete pouring, etc.), the equipment rental is usually broken out separately. Equipment rental costs make up less than 3% of new home construction - the vast majority of the work will be done manually by workers with power tools. For larger construction, this percentage will go up - going higher requires cranes, more expensive pump trucks, temporary elevators, more lifts, etc.

This seems like a small fraction, but it’s not obvious to me that it is. This study reports that for car manufacturers, the costs per unit of amortization and depreciation are just 10% of the manufacturing costs, 5.5% of the total sales price. The costs of this new car factory (2.3B for a factory capable of producing 300k cars a year) suggests something similar, that a factory and it’s equipment is a surprisingly small proportion of the cost of a car. So perhaps these equipment costs for construction are reasonable.

How the Breakdown Has Changed Over Time

An article in the June 1947 issue of “Fortune” published an article about Dave Bohanon, one of the WWII industrialized builders. It includes Bohanon’s entire cost breakdown. It’s interesting to compare the cost breakdown for a house built in 2021 to one nearly 75 years ago:

The results are...depressing. First, inflation adjusted cost has increased about 50% since 1945. Second, while it’s difficult to make a direct comparison, but it also appears that labor as a fraction of overall cost was similar in 1945 as well - just around 50%. Third, not only do we see almost identical systems and features in place. But their cost fractions are almost identical as well. Flooring, roofing, foundations, framing, painting, electrical - they all make up the same proportional cost of a home today as they did in 1947.

We do see a few small advancements. Expensive and labor intensive plaster has been replaced by cheaper drywall. (though drywall existed at the time). Finish hardware (door locks, hinges, etc.) is much cheaper (what we’d expect for highly manufactured items). But is this really it? What’s going on here?

It’s not as if there has been no innovation or progress. Within categories, there has been some innovation. Modern appliances are nicer and perform better. Modern electrical systems are safer, modern HVAC and insulation is far more performant.

Nevertheless, the picture here isn’t of an industry on the cutting edge of technology, or constantly reinventing itself. This is the exact reason why construction appears stagnant - in what other industry would this comparison be possible?

Partial Industrialization

I actually find the lack of change in the labor fraction of various trades somewhat surprising, given how much power tools have advanced over the last 80 years. Things like nailguns and saws seem like they should make a modern worker far more capable than a 1940s worker - the late 40’s was just at the cusp of portable electric power tools. But the above breakdown suggests that these haven’t driven down costs at all.

Perhaps the advance of power tools have simply compensated for increasing labor costs, by allowing the same amount of work to be done by a smaller amount of labor. This would explain why the fraction of labor in ENR’s cost-index basket has skyrocketed, but the fraction of labor in construction seems to have remained the same.

This is something that Richard Bender suggested in his post mortem of Operation Breakthrough - that things like power tools and window pre-assembly have effectively partially industrialized construction already, by reducing the amount of labor required. Perhaps this “partial industrialization” has prevented housing from getting more expensive, but hasn’t reached the point where it can reduce its costs.

[0] - Better data would be the actual receipts from actually built projects. This can be hard to come by, though I’ve compared it where I can to the above numbers and they mostly seem to align.

[1] - The largest fraction of expense might actually be the land cost, depending on where the home is. NAHB lists an “average” cost of just under $90,000 for the lot, but in low cost of living areas, the land cost will drop precipitously. It’s not uncommon to see brand new homes in sleeper suburbs priced very close to the cost of construction.

Feel free to contact me!

email: briancpotter@gmail.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/brian-potter-6a082150/

When it comes to construction costs, I agree that having a detailed breakdown is way better than just having an overall cost estimate. Having a detailed project breakdown can be beneficial for construction companies as this allows them to spot discrepancies for each factor that affect construction costs enabling them to address it accordingly. Trackunit also published an article https://trackunit.com/articles/construction-project-breakdown/ wherein they gave a detailed construction project cost breakdown along with other useful tips that can help provide construction businesses with more accurate construction cost estimates.

Appreciate it... Very concise showing estimates from past and those current...