Construction Costs Around the World: How Does the US Compare?

Welcome to Construction Physics, a newsletter about the forces shaping the construction industry.

With a few exceptions, this newsletter has focused mostly on building construction in the US. It’s what I’m most familiar with, and what I’m most confident in my ability to accurately contextualize. And if construction were a globalized marketplace, we might expect conclusions drawn about the US market to generalize around the world. But of course construction is NOT a globalized marketplace, it’s a hyper-local one. So different regions will have different construction traditions, use different materials, make different capital/labor tradeoffs, and so on. Once in place, building technology tends to be difficult to dislodge, and extremely efficient methods might not diffuse through the market. So it’s useful to take a look at construction costs around the world, and see if there’s any obvious improvements the US could adopt.

For cost data, we can use the Turner and Townsend International Construction Market Survey. This is a survey of 64 different construction markets around the world, that asks respondents for cost information about different project types, materials, and labor. As always, construction costs have a high variance, so these values should be assumed to have some wide confidence intervals on them.

Single Family Homes

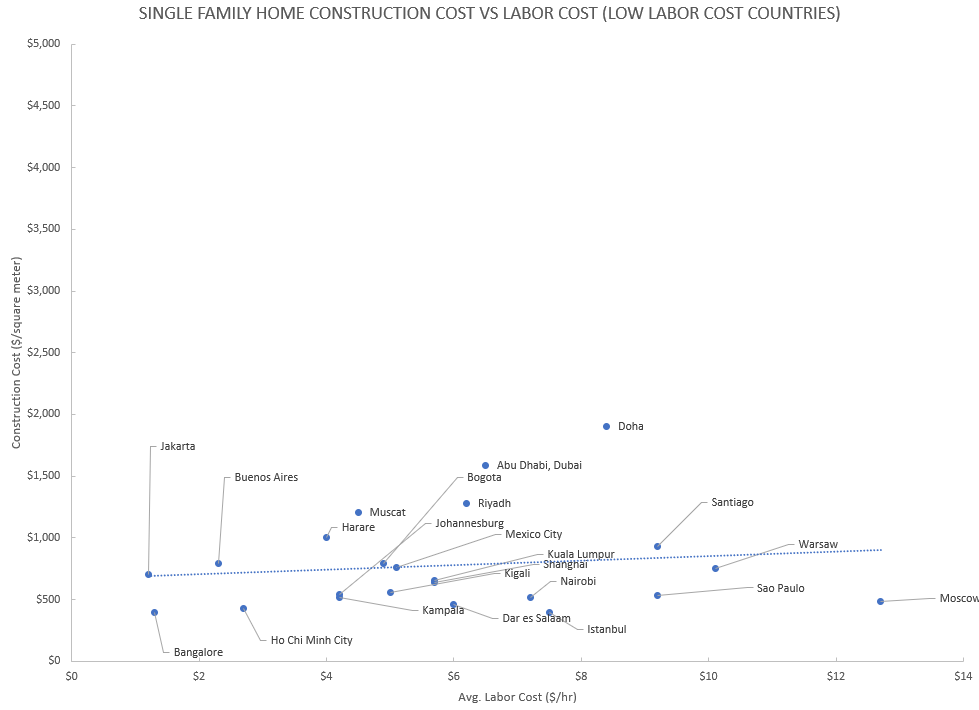

To start, let’s look at single family home (SFH) construction, the largest category by number of buildings in the US. The graph below shows average construction cost per square meter vs average labor cost [1] for a “medium quality” home (click to embiggen):

The first thing that jumps out here is how insensitive construction is to labor costs. Large increases in labor cost translate to very small increases in construction cost. Zurich has SFH construction costs just 3x those of Jakarta despite labor that’s 100x as expensive [2]!

And if we look closer, even the modest relationship between labor and construction cost starts to break down. We can roughly see two clusters of countries on the graph. One cluster consists of Africa, South America, the Mideast, parts of Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. These are the countries in the bottom left of the graph, which have very low labor costs and (mostly!) low construction costs. The other cluster is spread across the rest of the graph, and consists of high labor cost ‘western’ countries.

Within each of these groups, we see NO relationship between labor and construction cost:

This is surprising to me. We’re constantly told how construction remains a craft-based, labor intensive business, and yet we see almost no influence of labor on construction costs between comparable countries. It only seems to matter with respect to whether you’re in a rich western country or not.

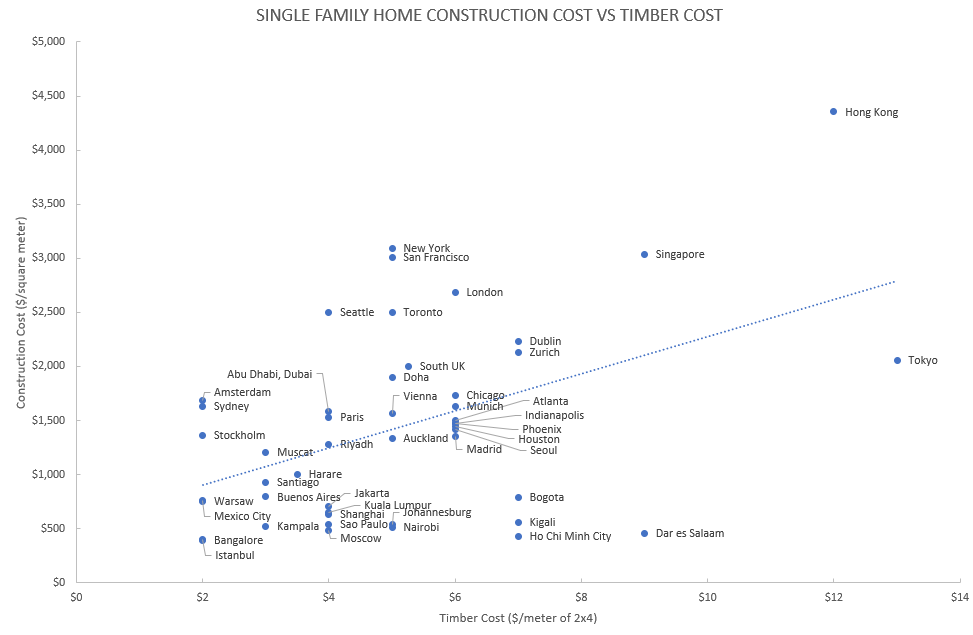

If we look at material costs, we see something similar:

We don’t see much of a relationship between timber cost and SFH construction cost - we don’t even see country clusters here. And most of what’s there is driven by non-representative outliers like Hong Kong and Singapore. Plenty of places with identical timber costs vary in construction cost by a factor of 6 or more.

So SFH construction doesn’t correlate much with labor costs or material costs. But there’s a large amount of variation to be explained, both between similar countries and within the same country. In the US, places like San Francisco and New York have some of the highest SFH construction costs in the world, whereas places like Atlanta, Phoenix, and Houston have some of the lowest among western countries (and compare favorably to the low labor cost countries) [3].

There’s a few possible mechanisms at work. One is that there’s actually a large amount of variation in quality between homes built in different countries that the survey doesn’t capture. Maybe “medium quality” homes in the US are built shoddier or unsafely compared to European ones, or are very energy inefficient, or are missing lots of features.

This probably explains some of the worldwide variation. But I don’t think it’s at work in low-cost US markets. As we’ve seen previously, homes built in the US are extremely long-lasting [4]. And despite an abundance of unsprinklered wood construction, the US also does relatively well on fire safety. And a comparison between US, Canadian, and European Energy codes found that US homes are roughly as energy efficient as European ones. As for features, this is purely anecdotal, but I’ve never seen anything in home renovation shows or YouTube home tours that would indicate that.

Another possible mechanism is that labor costs are a reflection of worker efficiency. Perhaps their higher cost reflects their higher skill - in engineering, a senior engineer might cost 2x what a graduate engineer does, but they’ll get things done 5x as fast.

Or if cost is independent of skill (through something like cost disease), higher labor causes management to use that labor more effectively, through better training, better tools, etc. If your labor costs go up, you find ways to use that labor more efficiently, so your overall costs don’t change much. I think these are both probably at least part of the explanation, but it raises the question why extremely expensive markets aren’t able to capitalize on this.

A third mechanism is differences in administrative costs. These can vary wildly by jurisdiction - Both New York and San Francisco have famously obtuse construction approval processes which require mountains of time and expense to navigate, and make them cost outliers in the US. This is possibly at work in Hong Kong as well. Under this model, construction cost would consist of a constant “cost to actually build the building” factor, and a variable administrative burden. I think this is part of the answer as well.

And of course, it’s always possible that the numbers are just wrong. They could be biased in one direction or the other, or reflect optimistic project cost predictions that won’t pan out, or fail to capture the use of undocumented labor in their labor costs. Survey data is not as good a source of information as measuring actual project costs would be. Or perhaps there are selection effects at work, and we’re comparing the least expensive US cities to the most expensive cities in other countries.

I think it’s highly likely the numbers are incorrect to some degree. But they do roughly match up with my own experience, and seem mostly in accordance with other sources.

Regardless of the mechanism at work, there’s not much evidence that the US is failing to adopt efficient SFH construction methods that are used elsewhere in the world.

Multifamily Construction

If we look instead at low-rise multifamily construction, the overall picture doesn’t change all that much:

We see the same country clusters, and mostly the same relative location of the different construction markets. One interesting thing is that while most markets have a higher cost of construction for low-rise apartments than they do for single family homes, the US markets all have a LOWER cost.

This, I believe, is almost entirely driven by construction type. For single family homes, it’s common to build them out of wood all over the world. But for larger buildings such as multifamily apartments, concrete or steel is largely used instead. Except in the US - here, we still build large multifamily apartments with wood, more or less the same way we build our single family homes. This lets us build multifamily apartments substantially cheaper than other western countries.

Once again, we see little relationship between material cost and construction cost:

Multifamily doesn’t change the picture much - if anything, it makes the US construction look even MORE efficient.

Other Project Types

But things start to change a bit once we start looking at larger, more involved project types:

The above graph shows the costs for several different project types, in several different cities both in the US (colored lines) and around the world (grey lines). On the left, we see that for low rise office projects, the trend is similar to what we saw with apartments or homes - the cheapest US markets are as inexpensive as other western markets. But as we move to the right, costs in even inexpensive US markets like Phoenix or Atlanta start to exceed those of European and Asian cities. For airports, US construction costs in ANY market are higher than anywhere else in the world (outside of Switzerland and Hong Kong).

The projects are arranged partially in order of project size and complexity, but this isn’t the whole story. The US still looks good on residential high rise construction, which are large and complex projects, and even a low-rise apartment complex can be huge in terms of building area.

A better interpretation is that they’re arranged in order of increasing administrative and government overhead. Universities, hospitals, and airports all have extremely involved project management processes, and huge amounts of government requirements and oversight. As administrative costs rise - the more involved the government is in projects - the worse the US does compared to other countries.

This tracks with US performance on infrastructure projects, where US performance is similarly government-involved and similarly poor.

This seems to confirm at least in part the administrative overhead theory, and suggests a model: Other western countries have a great deal of government involvement in all aspects of building. This makes much of their construction more expensive on average. But for projects which require a great deal of government involvement (such as hospitals or airports), this changes from a drawback to a benefit, as the higher quality of their civil service leads to lower project costs.

Construction Costs and Property Values

It’s also useful to see how these construction costs translate to real estate prices. For this data, we can turn to this study by Bricongne, Turrini and Pontuch. They used government and census data to find the total residential floor area, and total residential building value, for a variety of different countries (supplementing it with real estate data where needed). The result is the average price per square meter of residential real estate:

This mostly matches our previous conclusion - the US compares very favorably to other western, high income countries. And when you combined it with income data, you see what an outlier the US is:

The US (the country on the far, far left) has a housing / income ratio nearly half that of the next best country, and almost a third of the European average [5]. On a unit-area metric, the US builds some of the most affordable homes in the world.

Putting it All Together

So, to summarize:

We see almost no relationship between labor OR material costs, and construction costs for residential construction, outside of whether you’re in a western country or not.

The US does particularly well at building homes, apartments, and other projects that have low administrative overhead or government involvement.

The US does particularly poorly at projects with a high degree of administrative burden, government oversight, or where the government is a major stakeholder. European countries do far better by comparison.

There’s little evidence that US homes are built to worse standards than in comparable countries.

For residential construction, there’s little evidence that other countries have substantially more efficient construction methods that the US should adopt.

In the US, low construction costs translate to low property prices, making the US an outlier in housing affordability on a unit-area metric.

[1] Labor cost is the cost to the employer, and includes things like transportation, taxes, etc.

[2] GDP per capita is 82,000 USD in Switzerland, vs 3893 in Indonesia, a 20x difference.

[3] There’s a modest, but not perfect, correlation between low construction costs and metro area population growth in the US.

[4] Far longer than they will somewhere like Japan, which has a housing replacement rate 2x most other comparable countries.

[5] This is damped somewhat by the fact (and also helps to explain the fact) that the average US home size is much larger than the average European home size.

12/31 Update - PPP Adjustment

The Turner and Townsend Cost data uses exchange-rate adjusted costs to USD. However, it’s probably more accurate to compare using purchasing power parity (PPP) rather than exchange rate. Factoring by OECD and Worldbank PPP data yields the following for single family and low-rise multi family construction:

The overall picture doesn’t change much - we still see a weak relationship between labor and construction cost, and we still see the US performing better than most other western countries. The main difference is that the cluster of low-cost, low wage countries is more spread out, and less distinct.

Links

Fruit Walls - An urban farming technique from the 1600s. Fruit walls were fruit trees or vines grown next to a heavy wall with high thermal mass that would allow fruit to grow in climates that otherwise wouldn’t support it.

Tall, slender buildings often need some kind of damper to prevent the top from swaying back and forth. Often this is a tuned mass damper, a large mass on springs or oil. Rainer Square in Seattle uses two sloshing dampers, large tanks filled with water.

Site Selection Magazine is a publication about corporate real estate and building industrial facilities. Like most publications on hyper-specific subject matters, it’s a lot more interesting than you might expect.

Thank you for this piece! I think when people discuss construction in the USA they only focus on big infrastructure projects like highways, subways, airports, etc. These make the headlines with cost overruns, decades of time, etc. People wonder why we can't build like other countries, why it takes us 20 years to do one subway vs another country can do an entire system.

But your research shows the side that people don't consider and that is housing. America has relatively abundant and cheap housing compared to other countries and spacious as well. I do think this is a cultural difference also because other countries have people who are ok with smaller places in more urbanized areas vs America has the suburban sprawl effect. So there are unaccounted societal costs as well.

Overall great piece!

This would be a good paper to discuss!

Miller, T., (ed.), (1995), Multifamily housing in the USA & Sweden – A Comparative Study,

Trelleborg, The Swedish Federation for Rental Property Owners.