Construction Productivity: Structural Steel

This week we’re continuing our investigation of productivity trends in US construction. We previously looked at single family home construction, and noted that the number of hours required to construct 100 square feet of single family home has slightly increased over the past 50 years.

While I think this is a useful metric of construction productivity, it has some drawbacks. The primary one is that the content of a single family home has changed over time. A modern single family home has more insulation, a nicer kitchen, more bathrooms, etc., than a single family home built in the 1960s. So part of the lack of apparent productivity increase is due to an increase in quality. If people are spending slightly more hours to build a much better product, has productivity really stagnated? [0] One way to overcome this problem would be to look at a productivity metric that doesn’t have the issue of quality increase obfuscating the data.

One good task for this is structural steel erection. In steel buildings, the steel acts as the structural skeleton supporting the weight of the building. Unlike other aspects of construction, the output of this task (a structural steel frame) doesn’t change substantially over time. A modern structural steel frame is doing the same job, and will be designed for similar loading, as a building built 100 years ago. The Empire State Building has had many renovations over the years that replaced older building systems with more modern, better performing ones, but it still has its original structural steel frame.

(This is somewhat less true of design requirements for lateral forces, which have often increased as we gain a better understanding of wind and earthquakes, but it's still broadly true.)

Ideally, we would have a broad sample of the labor requirements for steel erection, but (as far as I know) such a dataset doesn’t exist. But we can look at individual buildings built at different times, for which we have enough information to make some productivity calculations. We’ll look at 3 different buildings - the Empire State Building (completed in 1931), the World Trade Center (completed in the early 1970s), and a 4-story steel building AISC uses as a university case study (completed in 2003).

These aren’t necessarily perfect comparisons. Though both the Empire State and the World Trade Center were once the tallest buildings in the world, and both were designed to maximize construction speeds, they have very different structural systems. And the AISC case study building is much shorter (4 stories vs 80-110 stories) and smaller (80,000 square feet vs millions of square feet), making a direct comparison difficult. The reduced size makes some erection tasks easier: more work takes place closer to the ground, reducing safety requirements, and piece pick times will be lower. But it makes other tasks (comparatively) harder: the large number of repetitive floors of skyscraper construction allow much greater learning curve effects than the smaller building. We’ll do our best to adjust for these factors.

The Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is famous for how quickly it was built. It opened roughly a year after construction started (demolition of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel that was previously on the site took an additional several months prior to the start of construction). This was fast, even for the time, but not uniquely fast: the builders of the Empire State Building had previously built another skyscraper, the 70-story Bank of Manhattan building, in 11 months.

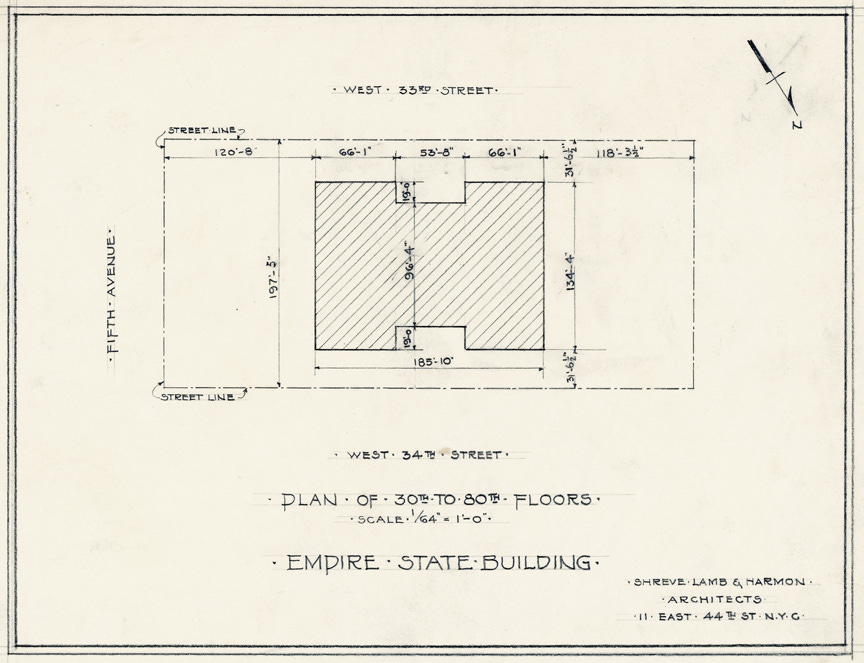

The Empire State Building had a structural steel frame that weighed 57,480 tons, and was erected over a period of 25 weeks - roughly 10,000 tons a month, or about 460 tons per working day (construction took place during a 5 day workweek.) The actual pace of setting varied somewhat. Much of the time spent during steel erection is on making the connections, which at the time were riveted joints. Larger, heavier members on the lower floors required less connection labor per ton of steel than lighter members on the upper floors. But 400-500 tons per working day was the average in the middle part of the building. At peak setting rates, the erectors were building a floor a day, almost 50% faster than the then-standard rate of 3.5 floors a week.

During August of 1930, at which point the erectors were near the 50th floor, the steel erector had 273 workers on site, operating 5 “guy derricks” to lift the steel into place. The floors from the 30th to the 80th have a floor area of about 23,000 square feet. At 460 tons a day, this gives an erection rate of 1.68 tons per worker per day, and 84.25 square feet per worker per day:

World Trade Center

The World Trade Center, unlike the Empire State Building, took an enormous amount of time to build. This was partly due to development delays, partly because of the size of the project (over three times the square footage as the Empire State Building), and partly because of outside factors (union strikes, EPA rulings requiring work to be redone, etc). But, like the Empire State Building, emphasis was placed on building the building as quickly as possible. Novel construction technologies like panelized construction, electroslag welding machines, and custom-built Kangaroo cranes were all used on the project with the aim of constructing it as quickly as possible.

According to the erector, the upper floors of the steel structure on the Trade Center weighed roughly 400 tons per floor. The World Trade Center used a specially designed lightweight structure about 40% lighter than a more conventional steel framing, making this the equivalent of 667 tons per floor if it was built in a “standard” way. According to the erector, it had “over 300” workers per building during the construction of the main portion of each building, with each building using four cranes. When their cranes weren’t breaking down and the work wasn’t stopped by strikes, the erectors could erect three floors every two weeks. Corrected for floor plate size, this is still slower than the Empire State Building (it’s roughly five Empire-State equivalent floors every two weeks, or about half as fast as the Empire State Building.) This is despite the fact that the builders used custom-designed, faster cranes, because they didn’t believe that guy derricks (the type of crane used on the Empire State Building, still in use in the 1960s) would let them build as fast as they needed.

On every productivity metric - tons per crane, tons per worker, square feet per crane, square feet per worker - the World Trade Center was significantly worse than the Empire State. And this is using the favorable “best case” numbers. Overall erection rates were even lower. The North Tower took 28 months to set the steel, roughly 3500 tons a month, just over a third of the overall speed of the Empire State Building.

AISC case study building

The AISC case study building is a far cry from a supertall skyscraper, but it’s still worth looking at it as another datapoint.

The example building is a 4-story, 80,000 square foot commercial office building, consisting of just under 1000 pieces of steel weighing 400 tons (or roughly 1 floor of either the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center.) It was erected by 7 workers over 38 working days, using a single crawler crane. This gives a tons per worker per day rate of about 1.5, much better than the World Trade Center, but slightly worse than the Empire State Building.

However, tons per day isn’t an ideal metric for comparing a low-rise building to a skyscraper. The case study building, being shorter, had a much lighter steel structure, averaging 10 pounds of steel per square foot of building compared to over 40 for the Empire State Building. The lighter the structure, the more connection work required per ton of steel, resulting in a comparatively high amount of labor per ton. From conversations with steel erectors, it seems 50 tons per day is closer to a typical setting rate for a larger, heavier structure.

If we look instead at square feet per worker per day, however, we get over 300 square feet per worker per day - almost four times as productive as the Empire State Building, and almost eight times as productive as the World Trade Center. However, now our productivity estimate is biased in the other direction. The heavier steel structure on a supertall skyscraper will require much more work per square foot of building than the lighter low-rise structure.

(If any steel erectors have any data on high-rise construction rates for structural steel, I would love to have it.)

So our low-end estimate has modern steel erection about as productive as the Empire State Building on a per-worker basis. Our high end estimate has it 4 times higher than the Empire State building. Assuming that “true” productivity is somewhere in the middle, it looks like modern steel erection is more productive on a per-worker basis than historic erection, though it’s hard to say by how much.

This is somewhat confirmed by RS Means cost data. Between 1998 (the earliest I have data) and 2023, the cost per square foot of erecting a structural steel beam and girder floor system rose from $4.50 per square foot to $8.16 per square foot. This is well below the level of overall inflation, and lower than the rate of construction wage increase. So steel erection, at least, seems to be getting slightly more productive over time.

[0] - I think in general people are too quick to use this to explain away construction productivity problems. A modern car is much higher quality than a car from 50 years ago, but the labor required to build a car has still steadily fallen over time. Most other goods (consumer products, electronics, etc.) have had both increases in features and falling prices.

I enjoy reading your blog. I grew up working construction side jobs alongside my dad who worked a full time, low paid, housing construction job. By the time I was older he had moved on to working for large maintenance contractors.

It seems to me that his original employers (in the 1980s) had little regard for the burnout of their employees and they were able to get away with low pay for very hard work. He was fortunate to move on to the larger companies who provided better pay and benefits while allowing for a safer and less intense work environment.

Many construction jobs still require roughly the same amount of physical work by laborers, but I think the expectations of the employees and requirements on employers have changed dramatically in the last hundred years (even just the last 40). Back when the Empire State building was constructed, laborers were expected to work harder with less safety restrictions.

One thing that I think is probably helping the employers at smaller construction firms is the supply of illegal immigrant labor. These laborers can be in a situation where the employers can hold them to lower standards of safety and pay that would be expected by the legal workforce. I also wonder about how accurately, if at all, this labor is recorded in statistics.

I'm sure you have already considered this at some point. Maybe you could send me a link to that article.

Thanks again for the interesting content,

Ask Morris Chang for a guest post! TSMC is right in the firing line, with unique experience abroad.