Debunking the "Housing variety as a barrier to mass production" Hypothesis

An idea I frequently encounter from urbanist folks is that a barrier to the efficient mass production of housing is the amount of variety people demand in their housing. People want unique homes, aren’t interested in living in a neighborhood of identical houses where their house is the same as their neighbors, and this variety is difficult to accommodate with any sort of mass production method. Thus, high construction costs are partly a function of needing to offer a wide variety of housing options to accommodate buyers’ tastes.

I think there’s little evidence to support this idea. Empirically, it seems like homebuyers are perfectly happy to buy houses in neighborhoods made up of many similar houses, and many (likely most) new housing developments in the US consist of a small number of floor plans copied over and over again.

For instance, here's a development by DR Horton (the largest homebuilder in the US), that's about 50-60 homes, with just seven different floorplans repeated over and over again.

Here's another DR Horton development that's several hundred homes, and is also just seven different floorplans repeated over and over.

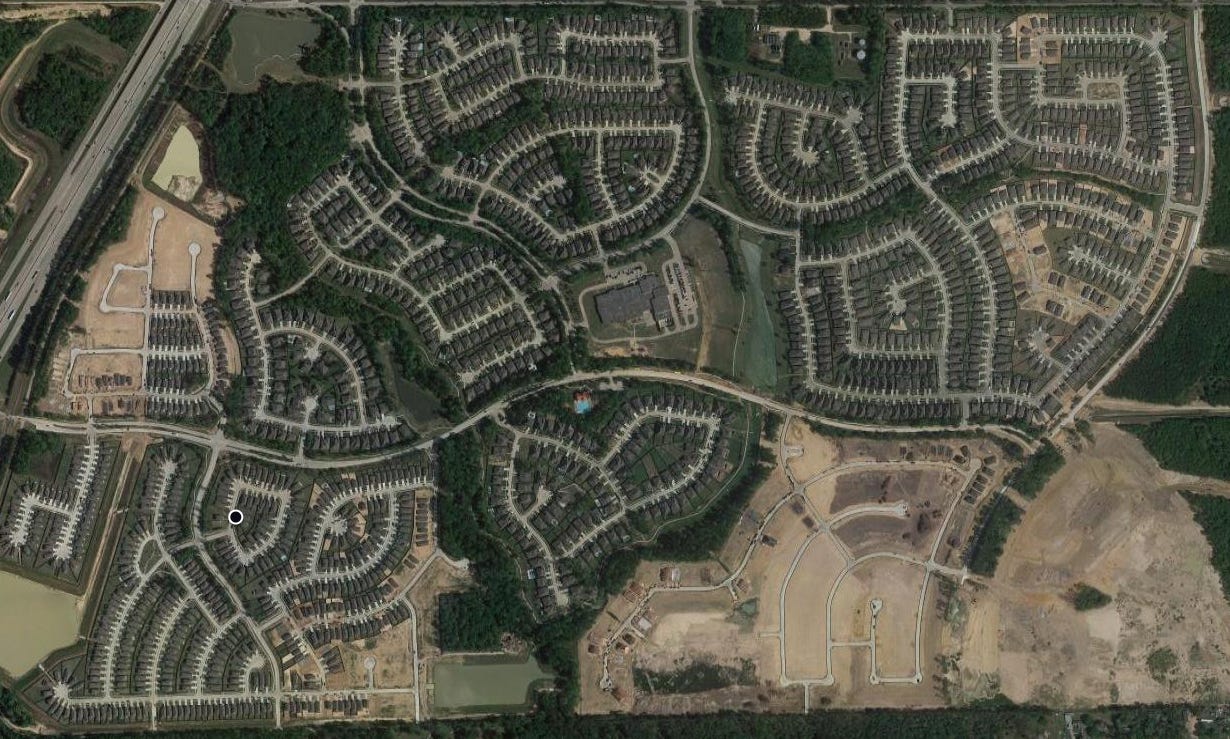

And here’s a huge development by Lennar (another large homebuilder) that consists of several smaller, subdevelopments of a few hundred houses each, each repeating the same 6-7 floorplans over and over again (though each subdevelopment has different floorplans):

I bought a newly built home last year, and it's this exact same development pattern - about 50-60 houses, with a small number of floorplans (my house is in a row of about 8 houses that all have the same floorplan). The same developer is building another development about 5 minutes away that's similar - a small number of floorplans repeated over and over again. My in-laws, who bought a recently built house a few years ago in a different state, live in a similar development of several hundred houses with a small number of repeated floorplans.

These are all single family homes. If you look at townhouses, you see even more repetition. These two developments in Atlanta by Pulte, for instance, each share the same two floorplans repeated over and over again (though they offer quite a few configuration options for them, letting you change some of the room layouts or adding an extra floor for the Briarcliff).

And if you look to the north of the second Pulte development on a map, you see two other townhome developments by other builders which also appear to be 2-3 designs repeated over and over again.

If you look instead at apartment buildings, you see the same thing - buildings or developments typically have a small number of units that just get repeated over and over again in different configurations. Here, for instance, is an apartment building in Atlanta with 285 units, and 12 different floorplans. Here's a development in Florida that's 300 units that has 9 different floorplans.

In fact, some multifamily developers go farther than this, and have standard buildings (where each building consists of a standard unit arrangement) that they just use over and over again on different developments.

So it doesn't seem like this hypothesis is true. To the extent that it seems true - in the sense that we do see a lot of variety in housing options - I think this is a function of a few different things.

For one, it's relatively easy to squeeze a lot of aesthetic variety out of few basic designs. By changing exterior colors and finishes, mirroring the floor plans, and making relatively minor tweaks (such as adding an entryway overhang, or changing a hip roof to a gable roof) your 7 different floorplans can quickly become a much larger number of configurations that don't necessarily look identical at first glance. If you look at floorplans for Lakewood, for instance, (a huge suburb built in California in the 1950s) you see each one typically had several aesthetic variations - different exterior trim, different types of roofs, etc.

Homebuilders will also often offer a lot of different finish options (different flooring, fixtures, countertops, appliances, etc.) that can easily be changed without fundamentally changing the design of the house. This sort of variation isn’t incompatible with mass production methods - car models, for instance, also have different trim levels, paint colors, interior materials and other configuration options that can be extensive.

Another factor is that the US homebuilding sector is extremely fragmented:

The top 4 homebuilders (DR Horton, Lennar, Pulte, and NVR) accounted for 20% of the single-family home market in 2021, compared to over 54% of the US market for the top 4 car manufacturers, and 75% of the market for the top 4 industrial robot manufacturers. As of 2017 there were an estimated 66,000 homebuilding firms in the US.

If we look at real estate developers, we see even more fragmentation. The largest US multifamily developers, for instance, build fewer than 10,000 units a year, or just over 2% of the 370,000+ multifamily units built in a year in the US.

These developers will all use their own floor plans and home designs. So a lot of housing variation is just a reflection of the fact that the US has a lot of homebuilders.

Housing also lasts a long time, and it tends to accumulate variation as it ages. Sometimes this is due to parts or components wearing out and being replaced by different ones - when my parents needed to reroof their house, they replaced their tile roof with cheaper asphalt shingles. Sometimes this is due to occupants adapting the house to better suit their preferences - the homes on my street, for instance, are less than two years old but are already starting to accumulate variation - people are adding outdoor terraces, or three season porches, or fences so they can let their dog out. Even a group of houses that start out identical won't be identical for long.

Similarly, housing trends change over time - different materials and styles come in and out of fashion, and changing demographics, wealth, family structure, or technology end up reflected in different housing styles. US homes got larger over time as the country got wealthier, the arrangement of the kitchen changed as it went from a utility room to family gathering and coordination room, people started to prefer more bathrooms. Materials become cheaper, or more expensive - 4 sided brick homes gave way to homes with brick on just the front facade, or just as an accent. So homes built in one time period will look distinct from homes built in previous time periods.

And housing variety is often imposed/demanded by other sources than the buyer. Sometimes different sites will demand different housing designs because of their layout, orientation, or other relevant features - if a site slopes on one side, for instance, that might require some houses to be split level, or have walk out basements, that the houses on flat ground don’t have. Sometimes floor plans might need to be massaged to squeeze enough rentable square footage onto a site to get the required return on investment. Sometimes zoning approval might be contingent on changing the amount of glazing or masonry used.

So overall, I don’t think buyers demanding large amounts of variation is a binding constraint on developing more efficient methods of building.

Interesting overview, and here’s a historical tidbit to further bolster your point: the old Sears Roebuck home kits came in a limited number of styles/layouts but were quite popular in the early years of the last century. My tiny Midwestern hometown had several. Apparently they were delivered by rail. (Not sure how inclined you’d be to dig deeper into the history there, but they clearly filled a niche.) Decades later those I saw seemed to be generally holding up well and had been modified extensively.

I think the idea is true to a very limited degree: yes, people prefer unique and distinctive houses but aren't willing to pay for them a significant premium. If cookie cutter mass production would bring a large productivity boost, that style would be dominant across all market segments except luxury/high end - because it would trickle down as cheap housing.

The fact that we don't see this dominance and that cookie cutters don't sell at a lower price than a comparable one off house suggests that the productivity gains of repetition are very limited. Or, in other words, that current production methods cannot exploit repetitive patterns to lower costs, unlike say the electronics or auto industries.