Does Construction Ever Get Cheaper?

I've mentioned a few times that I generally prefer looking at construction progress through the lens of cost indexes rather than productivity indexes. Whereas productivity indexes try to track changes in the amount of construction we get for a given amount of labor (for labor productivity) or labor + capital (for TFP), cost indexes try to track changes in how much construction we get per dollar. Cost indexes don’t measure the absolute cost of construction (in, say, dollars per square foot), but relative changes from a particular reference year.

I like cost indexes because a) they more closely track what I actually care about, the cost of construction, and b) I think they're more likely to be accurate than productivity indexes. In that vein, let's take a look at some US construction cost indexes, to get a better sense of how construction costs have changed over time.

There are many, many different construction cost indexes we could look at (see this Ed Zarenski page for a list of some of them), so we'll limit ourselves to a subset. We can roughly group cost indexes into three different categories. By comparing these cost indexes to other economic data like consumer cost inflation and GDP inflation, we can robustly track construction cost increases.

The first category of indexes is building cost indexes. These indexes track changes in the cost of actual finished buildings or other structures. I've picked some widely used ones that go back quite far:

The Turner Construction nonresidential index - this is a cost index produced by Turner Construction (the largest contractor in the US), which tracks changes in the cost of nonresidential buildings over time (since 1915). According to Turner, this index "is determined by several factors considered on a nationwide basis, including labor rates and productivity, material prices and the competitive condition of the marketplace.”[0]

The Census single family home constant quality index - This is an index produced by the US Census Bureau tracking the price changes of single-family homes. I believe it adjusts for "constant quality," to ensure it doesn't simply describe changes in home characteristics over time.[1] This index goes back to 1964.

The FHWA Highway cost index - An index produced by the Federal Highway Administration measuring the cost of highway construction since 1915. This index is based on a basket of several indicator items, which has changed over time - it used to be based on the costs of excavation, concrete pavement, asphalt pavement, reinforcing steel, structural steel, and structural concrete, but now includes many more items. Costs for each item are based on winning bids received for highway work.

The Handy-Whitman building index - An index produced by Whitman Requardt and Associates meant to track the price of reinforced concrete and brick utility buildings. Handy-Whitmanis also based on a basket of inputs, including material and labor costs, which gets checked closely against the costs and proportions of actual utility buildings. I’m not sure if this index gets produced anymore, but I was able to find data from 1915 to 2002.

Turner construction and Census SF are both “output” indexes, meant to include contractor overheads and profits. FHWA and Handy-Whitman are (I believe) “input” indexes (in that they track some basket of inputs), but I’ve lumped them in here because they’re meant to track a particular type of construction.

The second category is what we'll call combined input indexes. These are “input” indexes that track a generic basket of construction inputs, such as building materials and trade labor. I've once again chosen widely used ones that go back the farthest.

RS Means historical cost index - An index produced by RS Means, a widely used service for construction cost estimating. This index is a basket of many different construction materials and labor trades. I’m not sure how far back this goes, but I was able to find data back to 1953.

ENR Construction Cost index - An index produced by Engineering News Record which tracks a basket of several different goods - unskilled labor, steel, lumber, and cement. ENR changes the weights of these factors over time, and this index is now almost entirely dominated by the costs of labor. (ENR also has a "building cost index,” which is basically the same except it uses skilled rather than unskilled labor). [2]

There are also some combined input indexes that go back to the 1800s. The Riggleman index, constructed by John Riggleman for a doctoral dissertation in 1934, goes back to 1868(!) It combines several other indexes (such as the ENR index, and another combined input index from the American Appraisal Company) and other sources. The Blank residential index goes back to 1889 and tracks the cost of residential construction based on a basket of different building materials and trade labor.

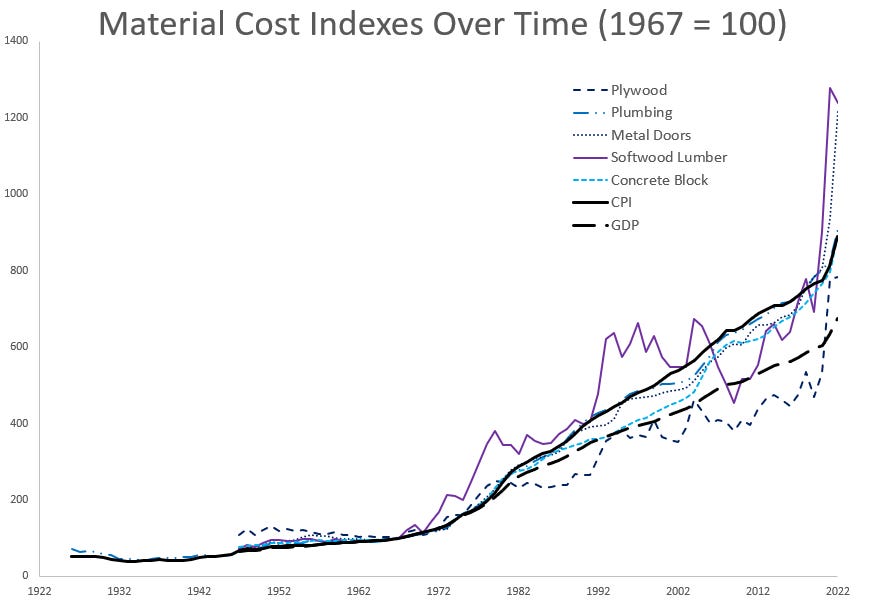

And finally, we'll also look at some building material indexes, created by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for a variety of different material classes. I've pulled out plumbing fixtures and fittings, metal doors, plywood, softwood lumber, and concrete block, as these give a reasonably broad swath of building materials and go back quite far (the plumbing index goes back to 1926, and the rest go back to 1947).

We’ll compare all three sets of construction indexes against two broader measures of price inflation. The first is the consumer price index (CPI), a measure of the price of a basket of consumer goods over time. CPI only goes back to 1913, so for dates before that we'll use a measure of inflation as produced by Robert Sahr. (I will refer to this entire measure as CPI for short.) The second is the GDP price deflator, a measure of price inflation in the overall economy produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This goes back to 1947.

Building cost indexes

We'll start with the building cost indexes (click to embiggen).

And to get a clearer view of pre-1970s changes, here’s a graph showing just through 1970:

We can see that building cost indexes have, in general, risen faster than CPI and GDP inflation. However, this view of the data makes it hard to spot trends in growth rates. So let’s instead look at the average yearly increase of each index, broken into 10-year chunks (ie: the average yearly increase between 1920 and 1930, between 1930 and 1940, etc.)

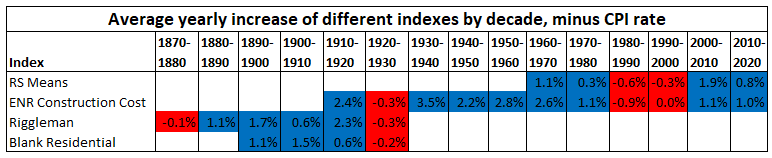

With this view of the data, we can see a few different trends. We see high rates of cost inflation across the board in 1915-1920 and 1940-1950 (WWI and WWII), as well as 1970 to 1980. Likewise, we see cost declines across the board between 1920 and 1930. Most of the time, the building cost indexes are growing faster than CPI and GDP inflation. We can get an even clearer view of this by looking at the same table with the CPI growth rate subtracted.

Blue cells are positive, meaning a growth rate higher than CPI. Red cells are negative, meaning a growth rate lower than CPI. Outside 1920-1930, and 1980-1990 (and somewhat in 1990-2000), each index is almost always growing faster than CPI inflation, in some cases substantially faster. What’s more, this isn’t a recent phenomenon, but goes back as far as we have data. The major exception to this is highway costs, which grew roughly in line with CPI inflation roughly until 1965 or so, and decreased enough in the 1980s that they didn't start breaking away from CPI until the early 2000s.

So going back to 1915, the cost of constructing buildings, as measured by various cost indexes, has almost always risen faster than inflation. For highways, construction costs rose roughly in line with CPI inflation until the early 2000s, after which they started rising faster.

This is frankly depressing data. Discussions of construction costs and productivity sometimes point to construction’s failure to innovate or adopt new technology as the culprit. However, the first half of the 20th century was a time of immense change in the technology used to construct buildings: increased use of structural steel and reinforced concrete (and methods for forming it), the development of power tools, etc. Yet this change doesn’t seem to show up at all in the construction cost indexes. It is of course possible there are measurement problems here, and the indexes aren’t capturing some changes. Nevertheless, I find it somewhat surprising that historical construction cost growth seems roughly similar to the cost growth we see today.

Combined input indexes

Let's turn now to combined input indexes. Here’s an overall view:

And here’s just up until 1970:

We see roughly the same pattern as we do with the building cost indexes. Between 1920 and 1930, and 1980-2000, construction costs rose more slowly than CPI inflation. In almost every other time period they rose faster.

We can once again see this more clearly if we look at the rate of change minus the CPI rate.

So, combined input indexes, which look at a basket of construction inputs such as materials and labor, roughly match the rate of increase as building cost indexes. This is true as far back as the late 1800s.

Building material indexes

If we look at building material indexes, however, we see a slightly different trend. Up until 2020 (when supply chain issues brought on by Covid resulted in a huge spike in material prices), all the material indexes tracked increase roughly in line with, or slightly below, CPI inflation (though in some cases, such as with softwood lumber, the rate is fairly uneven, and we see sudden spikes/drops).

If we look at the decade-by-decade view, the pattern doesn’t match the building and combined input indexes:

Much more red, much less blue. Outside of 1970-1980 and 2010-2020, almost every material index tracked consistently rose more slowly than overall inflation. Building materials, unlike construction, do seem to get cheaper over time.

Labor costs

If building cost indexes and combined input indexes (which include materials and labor) are both rising faster than overall inflation, but materials themselves aren’t, that obviously suggests labor costs are potentially driving the increase. So let’s take a look at construction labor costs. The below graph shows average construction wages as recorded by the BLS against the Turner Construction Index, the Census SF index, RS Means, and CPI, normalized to be equal at 1947 (the farthest back we have construction wage data). The Census SF and RS Means indexes have been normalized to be equal to the Turner index the year they start (1964 and 1953, respectively).

We see that the Turner, RS Means, and Census SF Index are roughly in the middle between CPI and wage increase. If the cost of building materials mostly track CPI, and the cost of construction is, roughly, half materials and half labor, this is more or less what we’d expect to see. This is also consistent with labor productivity in construction failing to improve.

If we look at the decade-by-decade view, we can get an even better sense of the changes:

Most of the time, the rate of construction cost increase has been slightly less than the rate of construction wage increase, but in the past 20 years that has changed somewhat. The Turner Cost index rose less than construction wages roughly until 1980, after which it rose more than construction wages. The Census SF index, except for 1970-1980, rose less than construction wages until 2010, after which it rose faster. RS Means index is somewhere in the middle, increasing more than construction wages in 2000 to 2010, but less in 2010 to 2020.

Conclusion

So to sum up, construction costs, as measured by various cost indexes, generally rise faster than overall inflation, as measured by either CPI or GDP inflation. This is true as far back as we have data, into the late 1800s. The major exceptions to this are 1920-1930, a period of price deflation (post WWI and the onset of the Depression) where construction costs fell more than CPI, and between 1980 and 1990/2000 (depending on which index you look at).

Building material cost indexes mostly seem to rise at or below the level of overall inflation, suggesting the problem isn’t that physical materials are getting more expensive. Increases in labor costs could plausibly account for it in most periods, consistent with construction labor productivity failing to improve.

Troublingly, over the past several decades years or so, cost trends seem to be headed in an even worse direction. Construction costs now seem to be rising well above the rate of wage inflation, and building material costs are rising faster than inflation (and this is especially true of the last 2 years.)

[0] - Turner has operations all over the US (and worldwide) today, but historically they were based on the eastern seaboard, so the older index values will be more reflective of eastern US construction than overall US construction.

[1] - The Census actually produces two indexes, a constant quality (Laspeyres) index, and a price deflator (Fisher) meant to compensate for substitutions in housing. More information about these indexes here. However, these indexes are virtually identical:

[2] - Weighting of the Construction Cost and Building Cost Index:

And here’s the change in the building cost index over time:

Could this be an example of Baumol Cost Disease in action? If another sector, such as automotive, was experiencing productivity improvements, then the value of one hour of work in the automotive sector is higher, and so automotive wages could rise. Many job-seekers who would have gone into construction can earn more in the automotive sector. So in order to attract new workers the wages in the construction sector would have to rise as well, even if there had not yet been enough compensating productivity improvement in the construction sector.

This is baffling. I think about the cost savings measures deployed in each of these trades. Those are not showing themselves anywhere.

For example, cordless nail guns and saws should result in much faster carpentry. And my experience with low-rise would lead me to conclude that this is the case. This should surely be reflected in the delivery costs. But it's not.