Every Building in America - an Analysis of the US Building Stock

Plus: Plenum Panels, a Design Build School, and Carbon Fiber Reinforced Wood

Welcome to Construction Physics, a newsletter about the forces shaping the construction industry.

Analysis of the US Building Stock

What does the US building stock look like, in aggregate? How many buildings are there in the country? How much space do they take up? What are they used for? Let’s take a look at the data and see what we find.

To do this, we’ll pull data from a few different sources. For residential buildings we’ll use the American Housing Survey (AHS), a HUD survey performed by the Census every two years, which we’ve used previously. It surveys a sample of over 100,000 housing units around the country, and provides data on a variety characteristics of the residential building stock.

For non-residential buildings, we’ll use the Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). This is a survey performed intermittently (generally every 6-9 years) by the US Energy Information Administration. It’s mostly geared towards information about energy usage, but it collects data on a variety of general building characteristics as well.

“Commercial Building” is a broad term, and the CBECS covers nearly every sort of non-residential building, both private and government owned, except a few:

Industrial or Manufacturing Buildings

Restricted access buildings (such as military bases)

Agricultural buildings

Non-building or non-enclosed structures (radio towers, signs, freestanding walls, etc.)

Parking garages

For information on Industrial Buildings, we can use the Manufacturing Energy Consumption Survey (MECS), a similar survey to the CBECS except for industrial buildings. The MECS doesn’t give quite as much building information as CBECS does, but it should work for our purposes.

For military buildings, we can use the Department of Defense Base Structure Report, which gives information on the real property owned by the DoD, including buildings.

This leaves agricultural buildings and parking garages. I wasn’t able to locate any publicly available information for either of these building types, so we’ll have to omit them. Unfortunate, as there are on the order of 2 million farms in the US[1].

I’m using the most recent version of each source available - the 2019 AHS, the 2012 CBECS, the 2014 MECS, and the 2017 Base Structure Report. As we’ll see, the building stock changes very slowly, so this shouldn’t distort our data too much. And as we’ve seen previously, data from these surveys is extremely noisy, so can’t be used for precise comparisons regardless. But it can give us a sense of what the large-scale patterns and trends in the building stock are.

(Summary at the bottom if you don’t want to look at 20+ graphs of building statistics).

Overview

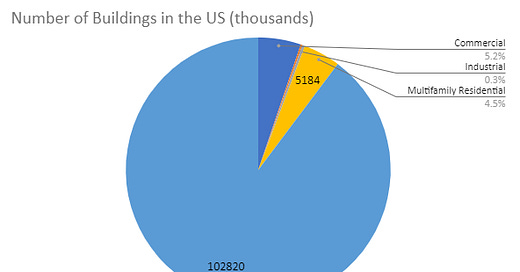

Using the sources above, we get the following. The US has, roughly:

100 million single family homes (SFH).

5.2 million multifamily residential buildings (everything from duplexes to large high rises), containing 40 million housing units.

5.5 million commercial buildings.

350,000 industrial buildings.

240,000 military buildings.

For around 111 million buildings total:

90% of the buildings in the US are single family homes, which I can’t decide if it’s surprising or not. But number of buildings doesn’t tell us how big they are, so let’s look at sector square footage[2] :

Residential construction still dominates, with over 200 billion square feet of single family home and another 36 billion square feet of multifamily. The US builds a truly enormous number of single family homes - most buildings are single family homes, and most building square footage consists of single family homes.

Of the remaining square footage, 25% is commercial (~60% of non-SFH construction), 10% is multifamily (~25% of non-SFH), and 3.4% is industrial (~8.5% of non-SFH).

Add it all up, and the US has around 340 billion square feet of building stock[3]. This is about 12,200 square miles, or 0.00032% of US land area - an area about the size of the state of Maryland.

Residential Buildings

Looking just at residential construction, we see that over 2/3rds of housing units in the US are single family homes (closer to 75% if you include manufactured homes). Most of the rest are in smaller buildings of fewer than 20 units, and less than 10% of US housing is in buildings with 20 or more units. Even if we consider only multifamily, only about 1/3rd of units in multifamily buildings are in buildings with more than 20 units. The types of construction done in major urban areas, such as tall residential high rises, or large multifamily apartment buildings, seems very representative of ‘typical’ construction. But it actually provides a very small portion of US housing.

We see similar results if we break it down by the number of floors in the structure. One and two story buildings make up almost 70% of housing units. Only 8% of housing units are in buildings more than 3 stories tall, and only 2.5% are in buildings more than 6 stories tall:

If we exclude single family homes and look just at multifamily buildings, we see an exponentially decrease in the number of buildings as building size increases. Small multifamily buildings with just a few units occur much more frequently than large buildings with lots of apartments or condos:

If we compare the above graph with the total number of housing units in each category, we see an interesting trend: despite exponentially decreasing numbers of buildings, the number of housing units in each size category is about equal (once you exclude single family homes). So there are roughly equal numbers of apartments in 10 unit buildings as there are in 5 unit buildings, as there are in 20 unit buildings, with the increasing size roughly balancing the decreasing frequency.

In other words, multifamily building size is roughly inversely proportional to frequency - buildings twice as large occur half as often.

If we look at the average size of housing units, we see that the average single family home size (excluding manufactured homes) is about twice as large as the average multifamily unit size:

Looking at the distribution of housing unit size, we see a right-skewed distribution of single family homes - very few single family homes are smaller than 1000 square feet, and there’s a long tail of 4000+ square foot homes. With multifamily housing units, we see the reverse skew - very few housing units in multifamily buildings exceed 1500 square feet. It’s effectively two separate classes of housing, with little overlap between them. This isn’t exactly surprising , but it’s interesting to see such a clear separation.

Overall, most residential buildings in the US are single family homes, and the housing that isn’t is mostly in small apartment buildings of 1-3 stories with 10 units or less. Large, sprawling apartment buildings or urban high rises are a small fraction of total US housing.

Commercial Buildings

Turning to commercial buildings, let’s first look at a breakdown by usage:

No major surprises here - the categories we’d expect to have large numbers (office, retail, warehouse, education, food service) are all represented at about the levels we might expect..

Breaking it down by square footage doesn’t change much (though it’s interesting that hospital square footage exceeds outpatient square footage).

Though offices might seem like a large category based on how much urban construction consists of large office buildings, office space is a relatively small overall proportion of commercial buildings. It makes up just 18% of total commercial building square footage, slightly more than warehouse space. There’s roughly 12 times as much single family home square footage as there is commercial office space, and roughly 2.5x as much multifamily square footage.

Looking at commercial building size, we see a similar pattern that we saw in multifamily residential: larger buildings are exponentially less likely to occur than smaller ones:

And we see a similar equal distribution of square footage across size categories. The rule “building frequency is (roughly) inversely proportional to size: doubling the size of a building halves its frequency of occurrence” seems to hold for commercial buildings as well. Buildings over 500,000 square feet (skyscrapers and massive distribution centers) occupy nearly as much total square footage as buildings less than 5000 square feet, despite occurring at about 1/350th as frequently.

The CBECS gives us a bit more data than the housing survey regarding distribution by number of stories. We see a similar pattern to residential construction, with most buildings being only one or two stories tall:

The data also includes buildings 10+ stories tall, but they’re such a tiny fraction of buildings that they don’t show up on the chart - just 0.23% of commercial buildings are taller than 10 stories. 90% of commercial buildings are less than 3 stories tall.

Breaking it down by square footage changes the picture slightly:

4-9 and 10+ story buildings are now healthily represented (4-9 story buildings are more common than 3 story ones, interestingly enough[4]). Nevertheless, tall buildings remain in the minority - only 6% of commercial building square footage is in buildings 10 or more stories tall, and 80% of commercial building square footage is in buildings 3 stories tall or less.

Commercial buildings overall show similar patterns to multifamily residential buildings: a large number of smaller buildings, a small number of larger buildings, with very buildings built more than 3 stories high.

Industrial Buildings

The MECS unfortunately doesn’t give us an in depth look at industrial building properties, focusing mostly on energy consumption. We have a rough number of buildings devoted to different activities:

And the same functions broken down by square footage:

No real surprises jump out at me. One interesting bit not represented here, is regarding transportation manufacturing:

One, car factories are truly enormous, averaging 2 million square feet. Two, auto manufacturing occupies only about a third of the building square footage as aircraft and aerospace manufacturing do. I’d never have guessed that.

How the Building Stock Changes

Let’s try to get a sense of how the building stock changes over time. This will be a challenge for a few reasons. As we’ve mentioned, these surveys have substantial error bars on them, making year to year comparisons quite difficult. Construction activity also varies quite drastically from year to year, depending on overall economic factors.

To combat this, we’ll compare survey results 30 or so years apart, and work out an average rate of change over time, but this will necessarily be a rough estimate.

Using data from the 1979 CBECS (which also includes industrial buildings) and the 1989 AHS (the first year median home size is available), gets us the following changes:

We see that the growth rate in the number of buildings is a little over 1% a year. This roughly matches the growth rate in the US population over the same time period[5]. But square footage of building stock grows at a rate significantly higher than the rate of population growth - the commercial building stock grows at 1.4% a year, the industrial stock 1.2% a year, and single family homes over 1.8% a year[6]. Based on these growth rates, we should expect residential to take up an ever increasing share of the building stock. If anything these trends should become more lopsided, with increased ecommerce and work-from-home shifting construction even further towards residential buildings.

Interestingly, these growth rates significantly lag GDP growth, which hovers around 2.5-3% per year. Most GDP growth evidently occurs without needing significantly new building stock.

Summary

Overall the US building stock shows the following trends:

Enormous numbers of single family homes - 90% of buildings, and 60% of building square footage consists of single family homes.

Most multifamily buildings (apartments, condos, etc) are small - only around a third of multifamily housing is in buildings with more than 20 units.

Large buildings are exponentially less likely to occur than small buildings - the US has a large number of very small buildings, and a small number of very large buildings.

Outside of single family homes, building size is roughly inversely proportional to frequency - every doubling in size roughly halves how often buildings that large occur.

Construction over 3 stories tall is very uncommon, even for large buildings. 90% of housing units and 80% of commercial building square footage exists in buildings 3 stories tall or less.

The total number of buildings grows roughly in line with the total population.

Building square footage grows faster than total population, but significantly slower than GDP. Residential square footage grows the fastest of all, indicating it will make up an ever larger share of the building stock over time.

[1] - 2 million farms, if each has on the order of 1000-10000 square foot of building.(barn, shop, equipment storage etc), that’s on the order of another 2-20 billion square feet of building, or around 5% of the total.

[2] - This probably slightly underestimates multifamily square footage, as it doesn’t include any public area square footage (such as corridors, amenity spaces or leasing offices).

[3] - Including additional multifamily space and agricultural buildings would push this to perhaps 375 billion.

[4] - I suspect some of this distortion is due to 2 stories being the cutoff beyond which an elevator is required, so many potential 3 story buildings are value engineered down to 2.

[5] - Not great news for the construction industry, as he population growth rate is trending downward in the US (as well as in most developed countries).

[6] - If we used these values to adjust commercial building square footage to the current year, we’d get about a 10% increase in commercial building square footage.

Elsewhere

Yestermorrow Design Build School - School (college?) in Vermont that teaches hands-on courses in house design, but also construction, timber framing, cabinetmaking - everything you need to design and build a house, basically (with a somewhat sustainability bent to it). I suspect one of the reasons for the slow pace of construction advancement is the huge disconnect in the industry between building design and building construction, so I’m interested in seeing attempts at tightening that feedback loop.

Plenum Panels - Billed as an alternative to CLT, these are stressed skin floor and ceiling panels made out of dimensional lumber and top and bottom OSB flanges. The big difference with CLT is that where CLT is a solid mass of timber, these have void space between the flanges. Interesting as a potential thin flooring option (the spans seem to beat what you’d get for shallow wood trusses), but I don’t see it competing with CLT. If you’re speccing CLT you want the look of large timber elements, not OSB sheathing.

Apartment for sale in detroit - Some really amazing masonry work on this building, hopefully someone shells out the $35,000 (plus whatever would be required for restoration). No matter how much you design a building to last, it’s survival will ultimately be mostly a function of regional economic circumstances.

Fiber Reinforced Wood - The wood equivalent of reinforced concrete - an engineered lumber with carbon fiber layers at the outside edges. This actually seems like a really interesting material, that doesn’t require any radical rethinking of how a building goes together. There doesn’t seem to be any available information on it other than press releases from the company that makes it though.

Thanks for this study! Its really nice to see the numbers broken down like this.

Thank you for compiling this data. One additional thing I was trying to research is commercial building permits annually and, of those, their segmentation by company size. Did your research for this article point to data sources for this? Glad my Googling brought me to Construction Physics!