Factory Built Homes? It’s More Likely Than You Think.

Plus: Bone Structure, Minimum BIM, and ICC Lawsuits

Welcome to Construction Physics, a newsletter about the forces shaping the construction industry.

The Manufactured Home

In the late 1960s, the Department of Housing and Urban Development launched “Operation Breakthrough”, a $72 million[1] program aimed at increasing the supply of low-cost housing by funding developments in industrialized, factory built housing. The hope was to kickstart development of factory built building technologies by funding housing projects that would specifically utilize them.

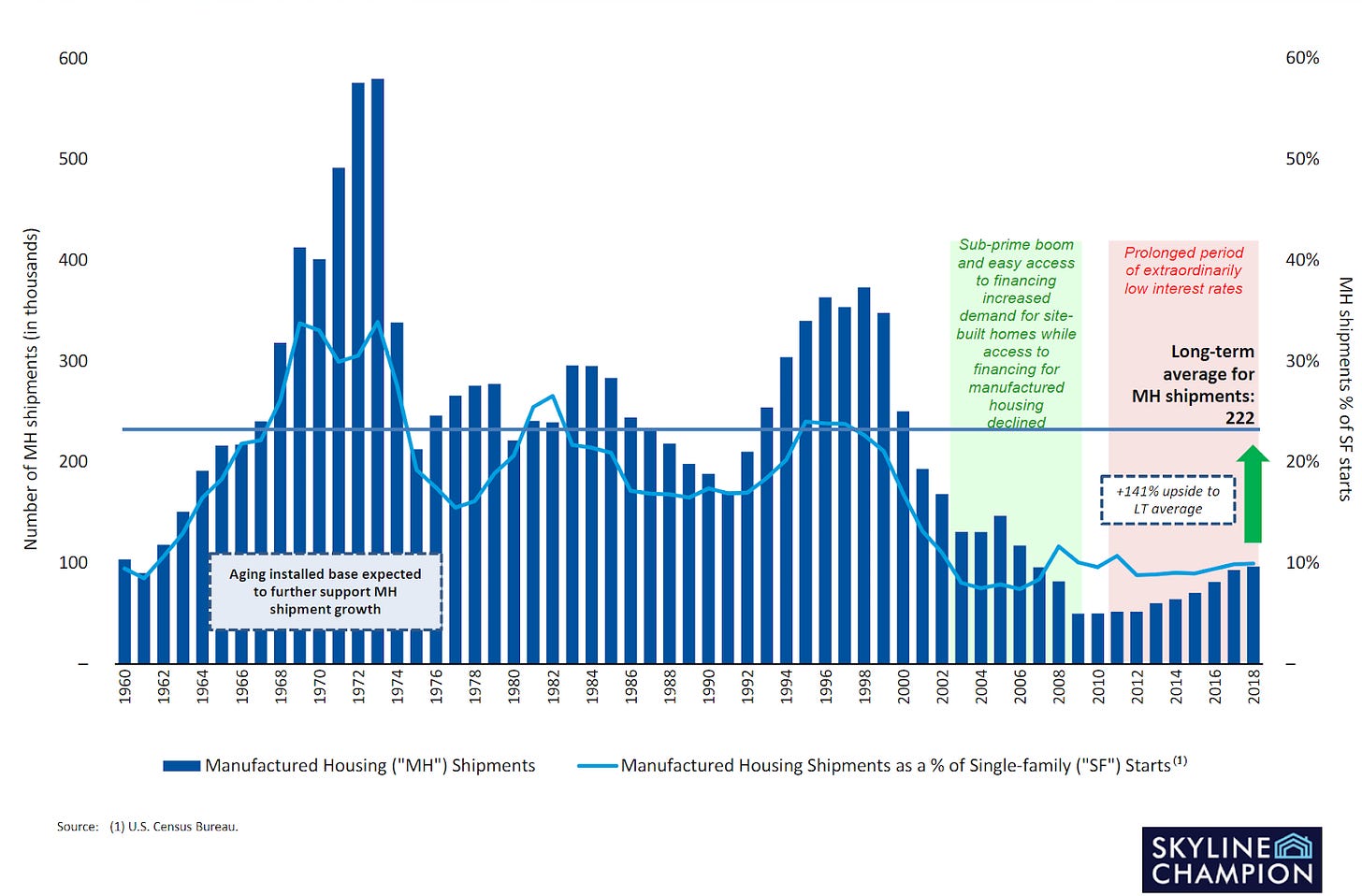

Operation Breakthrough ended in 1973, after building around 25,000 homes, and failing to effect any major change in the construction industry. But during the same four years, nearly 2,500,000 manufactured homes had rolled off the assembly lines, peaking at nearly 60% of new single family homes sold:

This is typical of the manufactured home industry - it exists in a strange parallel world to conventional construction, where people in the construction industry seem mostly unaware of it. Even designers and entrepreneurs calling for the need to change the construction industry and embrace prefabrication seem to act as if the manufactured home industry isn’t already supplying tens of thousands of low-cost homes a year.

“Manufactured home” is a specific industry term, meaning a home that conforms to the Federal Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards instead of the state building codes that normal construction must comply with. Also referred to as a mobile home or a trailer, it’s defining feature is a steel chassis underneath the home that (theoretically) allows it to remain portable[2]. They’re distinct from modular homes, or modular construction, which must conform to state and local building codes. Manufactured homes can always be spotted by the presence of a steel chassis underneath (though it may be hidden by a skirt).

True to their namesake, manufactured homes are built almost entirely in factories. They’re moved along by assembly line, with workers attaching components at each stage. Nearly everything will be installed in the factory - walls, roof, plumbing, electrical, appliances, fixtures, finishes, etc. Once completed, a home will be transported by truck to the jobsite, set in place, and attached to any neighboring modules - homes are generally “single wide” (a single module) or “double wide” (two modules attached together).

Currently in the US, roughly 10% of new homes are manufactured homes, just under 100,000 a year. But this is a near-historic low, down from nearly 400,000 per year in 2000 and nearly 600,000 in 1972. The number of manufactured homes built plummeted in the early 70’s following the introduction of the HUD code, which introduced stricter building standards for their construction. They cratered again in the early 2000s due to a combination of increased subprime lending for standard mortgages and a collapse in manufactured home financing[3].

Manufactured Home Construction

Manufactured homes are built with the same basic framing as a typical site-built home: 2x4 or 2x6 balloon frame walls, sheathed with OSB, and topped with wood roof trusses. One major difference is that the HUD code tends to reference older design standards than state building codes do. Wind design, for instance, is based on the 30-year-old ASCE 7-88, whereas building codes use either ASCE 7-10 or 7-16. Another difference is that manufactured homes will use a stressed-skin design for the structure. Stressed skin uses the sheathing as a load bearing element, and lets a manufactured home wring the maximum possible capacity from its structural elements.

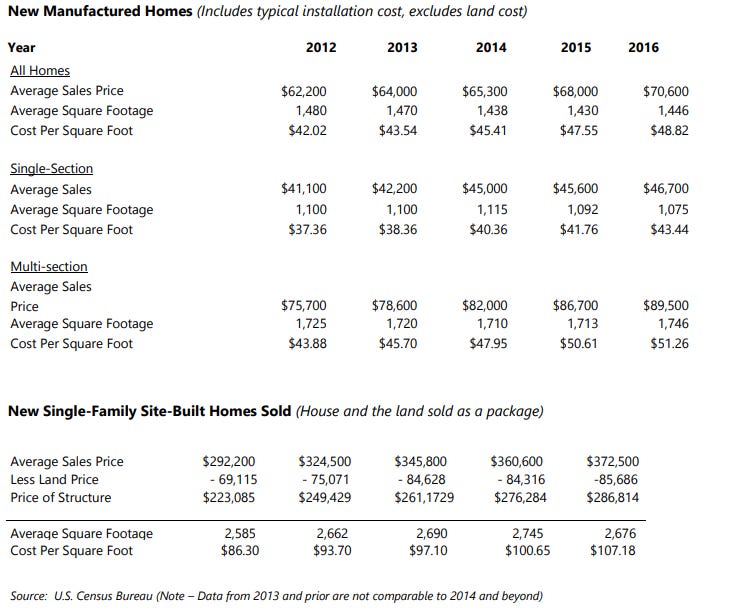

This economizing on material extends to the rest of the home as well. Interior walls are generally 2x3s instead of 2x4s. Low-cost vinyl-on-gypsum panels are often used instead of drywall (which is why walls will often have visible seams). Where drywall is used, it may be thinner than in site-built. Vinyl siding, linoleum flooring, laminate counters, and Formica cabinets are all the norm. Appliances such as water heaters and refrigerators might be smaller (30 gallon water heaters seem to be extremely common). Material cost is a substantial portion[5] of the cost of a manufactured home, and being ruthlessly efficient with materials is part of what allows manufactured homes to cost around half that of typical construction, a number which would be even lower if they weren’t required to be attached to a heavy steel chassis.

In cases where the HUD code requires a specific material or technology, manufactured home builders are able to substitute it for an alternative material or system, so long as they can demonstrate that it meets or exceeds the code-required performance.

This provides a useful canary for evaluating supposedly more efficient building techniques or technologies (for light frame construction, at least) - if it’s actually more efficient, it’s likely the manufactured home industry would have adopted it.

For instance, builders are perpetually evaluating whether cold formed steel can be used to frame a building as efficiently as wood can. Studies suggest close parity between the two, and plenty of construction startups have opted for CFS as their framing material. HUD actually published a prototype CFS manufactured home, suggesting that the industry pursue it. But the industry has declined to implement it, and continues to use light framed wood as its material of choice.

If manufactured home prices are driven largely by material costs, it suggests there's not an easy path forward to dramatically less expensive construction. Complex products get cheaper over time as we get more adept at manufacturing them, but we shouldn’t expect any large decreases in the price of gypsum, dimensional lumber, or asphalt shingles. What’s more, many of the materials manufactured homes economize on are “visible” ones - flooring, countertops, wall coverings, siding - and nicer models that use higher-end finishes start to approach the cost of site-built homes. The invisible materials that occupants don’t see, such as wall studs or PEX piping, are more or less the same as conventional construction, suggesting there aren’t any obviously cheaper options that conventional construction could be using.

Manufactured homes are one of the few building types that are decoupled from the land they sit on - the purchaser generally needs to buy the land separately (though around 30% of manufactured homes do get placed in manufactured home communities). Separated from location concerns, consumers are free to compare homes directly, making it interesting to see what features they offer, and what builders don’t skimp on.

The master bath, for instance, is often extremely nice: large, tiled showers, his and her vanities, jetted tubs, etc. Likewise, the kitchens are often full of the same features you’d expect in a site-built home: large islands, large sinks, can lighting, and so on. Fireplaces often make an appearance, though they’re generally electric. You can often spot a fancy thermostat. To appeal to as broad a customer base as possible, manufacturers offer a wide variety of price-points, from low-end singlewides to high-end doublewides or larger.

Further Optimizations

Other than economizing on materials, manufactured home suppliers are able to achieve such low prices by relying on alternate sources of revenue (much like Costco). Skyline Champion sells transportation services through Starfleet Trucking. Both Clayton Homes and Cavco (combined around 60% of the manufactured home market) offer financing for the homes they sell. Cavco makes 20% of its profit from its financial services division, and Clayton, in addition to offering home financing, also offers insurance.

They also structure their operations to minimize logistics cost. The industry is highly consolidated, with the top 3 firms (Clayton Homes, Skyline Champion, and Cavco) controlling nearly 80% of the market. These firms have many fabrication facilities (Clayton 40, Skyline 38, and Cavco 20) located close to the markets they serve. Manufactured homes, like most offsite construction, are limited to a delivery radius of 300-400 miles - beyond that, transportation costs become too high. A factory will generally be sized by the size of the market it can serve, which in turn is a function of the population within the delivery radius.

Homes are built essentially as wide as transportation laws will allow - the homes have gotten wider as the transportation laws have changed to accommodate them (40 years ago few states allowed 14 foot wide homes to be transported, now that has become the standard home size). And despite their size, they can be installed with a small crew without using a crane.

Manufactured homes have had trouble escaping their reputation as poorly constructed, low end, and low status. This isn’t entirely without merit, as manufactured homes have a much shorter lifespan than site-built homes. Whereas site-built homes can potentially last for hundreds of years, manufactured homes last substantially less than that: HUD gives an average life of 30-55 years. And where a site-built home tends to appreciate in value, a manufactured home will lose value if it’s not financed as real estate[6], which few are. They’re generally financed as personal property, and subject to higher interest rates than typical mortgages.

[1] - $482 million in 2020 dollars.

[2] - However, vanishingly few manufactured homes are ever moved once they’re installed.

[3] - The collapse in the manufactured home mortgage financing seems to be the result of the widespread failure of overrated mortgage securities, which would repeat itself in the site-built home market a few years later.

[4] - Much like a car assembly line, this labor appears to be largely unskilled. Job listings for Clayton Homes mostly don't list specific jobs, just things like "home building team member".

[5] - The 1980 report on manufactured homes “Building the Future” says material costs make up 65-70% of the cost of a manufactured home. A promotional video from Palm Harbor states that labor makes up less than 20% of their costs, implying material costs continue to be a substantial portion of the cost.

[6] - Though homes that are financed as real estate seem to appreciate similarly to site-built homes.

Elsewhere

Bone Structure - Another prefab construction startup, but this one seems like it’s done it’s homework. The founder investigated the long, storied history of prefab construction to find out why previous efforts failed, and designed their system accordingly - it’s designed to be easily assembled with extremely simple tools, not unlike flatpack furniture (another metaphor construction startups are fond of). Ultimately I think the use of custom fabricated steel sections as a structural system will consign this to limited applications, but I’ll be interested to see how it develops.

Minimum Viable BIM Data - A useful lesson in BIM management. Keeping your BIM models accurate and up to date has a maintenance cost, and the more data you have, the higher this cost is. It’s very easy for the maintenance cost to exceed the value of the data you’re providing. This applies to most aspects of design in my experience.

ICC is back to suing people who put building codes online for free.

Great re land decoupled from manufactured homes, transportation laws for homes, and how they're financed as personal property, thanks.

2x3 interior walls sounds noisy. Any way to deal with this that isn't as expensive as going with thicker interior walls?