Several people have asked me about a new NBER working paper that takes a look at construction productivity (a popular topic around here), “The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the US Construction Sector,” by Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson. This paper doesn’t bring any new data to bear on the construction productivity question - it uses the same Bureau of Economic Analysis data that previous analyses have used - but it does try to somewhat systematically look for causes behind construction’s apparent productivity decline.

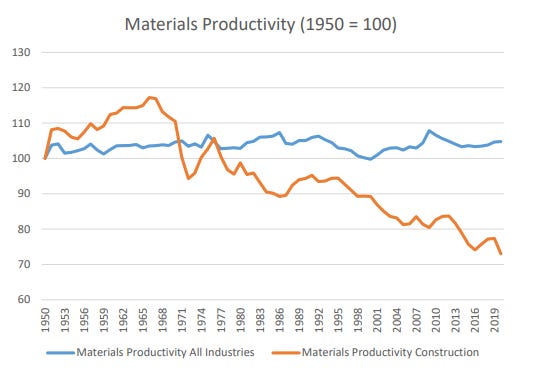

The paper starts with what should by now be a familiar graph. While the US economy overall has seen steadily increasing productivity, construction productivity (both labor and total factor productivity, which is labor + capital) has been steadily declining. As the authors note, “By 2020, while aggregate labor productivity and TFP were 290 percent and 230 percent higher than in 1950, both measures of construction productivity had fallen below their 1950 values” (emphasis added). The authors note that construction productivity actually increased faster than the overall economy from 1950 to ~1965, after which it steadily declined.

If you’ve previously spent time looking at construction productivity graphs, you’ll notice that this decline looks much worse than some other analyses. Construction labor productivity declined around 40% between 1964 and 2012 as measured here by the BEA, compared to only 20-25% as measured by Teicholz 2013. We’ll come back to this.

Goolsbee and Syverson look in several places for potential explanations for this decline. They start by looking at capital investment: maybe the lack of productivity growth is due to failure to invest in labor augmenting equipment and machinery, or in intangible capital like IP. But they find that over 1950 to 2020, capital stocks in construction increased roughly in line with the overall economy (though its growth is pretty uneven). And capital per employee grew slightly faster than the overall economy.

(As an aside, I’ve previously mentioned the need for caution when looking at capital and productivity. It is very easy for capital investment to increase labor productivity (in the sense that less labor is required) without decreasing costs (because the equipment costs as much or more than the labor it displaces). And in fact we frequently see this in construction - it often takes a lot of expensive equipment to automate or mechanize what a relatively small amount of labor can accomplish.)

The authors then turn to potential measurement problems. Maybe what looks like a productivity decline is actually due to mismeasurement of one or more of the relevant factors (labor, capital, output, etc). They look at three different measurements of labor (two from the BEA and one from the BLS), which mostly track each other, and have no obvious “kink” in 1965. There’s also no increase in labor growth rate after 1965 in those labor measurements (labor input actually grows more slowly after 1970 than before), which suggests the productivity decline isn’t due to labor being measured incorrectly.

They also rule out capital mismeasurement, as the rate of capital increase seems to more or less track the overall economy, and mismeasurement of capital wouldn’t account for the decrease in labor productivity that we see.

They then look for problems measuring output. Construction value add, as measured in dollars, has been a fairly consistent fraction of the overall economy between 1950 and 2020, slightly abovee 4%. This means that the observed productivity slowdown must be coming from the deflator being used, where “deflator” is an adjustment to the dollar value to correct for price inflation over time. And indeed, if we look at the deflator the BEA uses for construction, in 1965 it started to increase much faster than the GDP deflator (a measure of price inflation in the overall economy). In other words, according to the BEA, since 1965 the price of construction has risen much faster than the level of inflation in the rest of the economy.

They also note that if you adjust construction output using the GDP deflator instead of the BEA’s construction price deflator, the productivity decline goes away.

The observed construction productivity decline in BEA data thus depends on the accuracy of the BEA’s construction price index. The authors note that some other work in this area (Sveikauskas et al. (2016, 2018) and Garcia and Molloy (2022)) tries to use more accurate deflators, and finds a less extreme productivity decline.

To get a better sense of how accurate the BEA’s measurement of construction price inflation is, I graphed it against some other measures of construction prices - the Census single family home index (which estimates the price of a particular single family home over time), and RS Means’ 30 city cost index (which gives an average construction cost increase for 30 major US cities). I also included the GDP deflator, and the consumer price index (CPI), probably the most common measure of inflation (click to embiggen).

We see that while all construction cost indexes (Census, BEA, RSMeans) increase faster than both GDP inflation and CPI inflation, the BEA’s index starts to increase much faster than the others around 2000. This is partly why this BEA measurement of construction labor productivity looks worse than other measurements of construction productivity such as Teicholz’ (which looks at a variety of deflators, but not the BEA’s).

But even without this divergence, there still seems to be some difference in the BEA’s estimate and other sources. BEA estimated productivity dropped much more between 1964 and 2000 than Teicholz’ estimate, which uses census and BLS data. It’s not clear to me why this is, given that (as far as I know) the BEA uses census data for its measure of construction output, and BEA and BLS measures of labor inputs seemed to align.

How does the BEA construct its construction price index?

I wasn’t able to find a current detailed breakdown, but it seems BEA combines a bunch of different cost indices. Here’s the breakdown the BEA has used at different times (BEA I, II, and III correspond to 1961, 1974, and 1988 methodologies respectively)

According to SRMPY 2016, the BEA switched its deflators in the early 2000s to include the BLS building-specific adjustment deflators. The BEA’s website describes the factors used for construction price adjustments (the top is residential, the bottom is non-residential).

So the BEA adjusts for construction price inflation with some combination of price and cost indices, which seem to yield a higher price increase than other measures, such as RS Means and the Census single family home index. This high measure of price increase is partly why the BEA’s estimate for construction productivity decrease is particularly high.

Goolsbee and Syverson try to look at what the source of construction price increases might be. They find that the price of “intermediates” (goods and specialty services that the industry purchases) has increased roughly in line with the overall economy, suggesting it's not a contributing factor. And they find that a labor cost increase likewise can’t explain it - construction salary growth is slightly higher than the overall economy, but not nearly enough to explain the magnitude of the price increase. Similarly, increase in capital costs doesn’t appear to be the culprit.

If input prices aren’t responsible for increasing costs, maybe it’s increasing profit margins (“markups”) in the construction industry. They find that, while these have increased very slightly, they’re likewise nowhere near enough in magnitude to explain the price increase.

Because “construction productivity” lumps in a lot of separate construction types - single family home, high rise, heavy civil - it’s possible that this increase is due to a certain type of construction getting much more expensive. The costs of highway construction, for instance, have risen extremely fast in the last 20 years (though I doubt this on its own would be enough to shift the BEA’s estimate up so much).

Because of potential issues with the construction price index, Goolsbee and Syverson also look at other measures of construction productivity that don’t require a deflator adjustment.

They first look at "housing units per employee." Using two different data series (one from 1990-2022 which breaks out single family and multifamily separately, and one from 1972-2002 which combines them), they find that housing units per employee has declined over time. Because the character of housing units has changed over time (notably, the average size has significantly increased), they adjust for the average size of homes built each year to get output per employee in terms of square footage.

With this adjustment, they find some conflicting results. Using the older 1972 dataset, they still find a productivity decrease. Using the 1990 separated dataset, they find a (nonsignificant) productivity decrease in multifamily construction, but a productivity increase in single family home construction. The productivity increase is about an additional 37 square feet per employee per year, or 0.5% growth rate, significantly less than the average 2% annual increase in productivity in the overall economy. A further complication here is that the newer dataset seems to give a much higher absolute productivity (in terms of square feet per employee) than the older dataset during the period of overlap, 1990-2002.

They also look at what they call “materials productivity” - amount of output per unit of “intermediates,” where “intermediates” is both purchased materials and purchased services (ie: subcontracting). They find that, along with labor productivity, materials productivity is also declining - it's taking more and more contractors and materials to get a given unit of output, something we don’t see in the economy overall.

Combined with a finding that construction’s value added share of total construction output over time is increasing (it went from 0.4 to 0.5 between 1950 and 2022), Goolsbee and Syverson interpret this as construction using more and more labor + capital, and fewer intermediates (materials + services) as it gets worse at converting them to output.

I find it somewhat difficult to make sense of this finding. This paper, as well as other papers, seem to suggest that “specialty” subcontractors such as electricians and plumbers would be counted as an intermediate input. But in general, large amounts of construction work is subcontracted. As Sveikauskas et al note:

We find that subcontractor labor is an important part of total labor hours. In 2012, subcontractor labor accounted for 44.2 percent of total labor hours in single-family construction, 74.5 percent in multifamily construction, 43.2 percent in highways, and 84.9 percent in industrial construction.

Because of the high level of subcontracting in construction, It’s virtually impossible for a builder or general contractor to create half the value added on a construction project. For example, if the general contractor subcontracted half the work on a job, and did the other half of the work themselves, that would imply a roughly 0.25 value added fraction. Half the value would come from subcontracted work (labor + capital + materials), a quarter would come from the general contractor’s labor and capital, and (roughly) a quarter would come from materials the general contractor purchased. Even if the general contractor didn’t subcontract anything, and performed all the work themselves, roughly half the value of construction would still be from materials (an intermediate input), so if subcontracted labor is ALSO an intermediate input, I would expect to see a much smaller “value added share” from construction. So I’m somewhat confused about the measured 0.5 value added share of construction output. [0]

Finally, Goolsbee and Syverson also look for shifts from low-productivity producers to high-productivity producers: whether states with higher productivity see a greater share of construction value over time. They don't find this. If anything, there appears to be a slight negative relationship between construction productivity in a state and fraction of construction value growth. More productive states see less construction value over time, rather than more.

To sum up - raw data from the BEA suggests a large decrease in construction productivity starting around the 60s (the kink). Lack of capital investment, mismeasurements of labor and capital inputs don't seem like they can be the cause. Neither does input price increases or increasing profit margins. This decrease is much larger than other analyses suggest, and seems to be partly driven by a significant increase in the BEA’s construction price index compared to other indexes starting around the year 2000, the source of which is unclear.

Other measures of construction productivity are less consistent. Output per square foot for housing construction seems to have increased by some measures (though not with other data sets). Intermediate use productivity has also declined, but it is unclear (to me) how much this means - construction subcontracts so much that it's just hard to make sense of this as a metric.

Overall, I found it an interesting paper, particularly the investigations of capital growth rate and whether construction moves to high-productivity states: both results surprised me. And I agree with Goolsbee and Syverson’s conclusion, that “the productivity struggle is not just a figment of the data. It is real.” But in general, I find these highly abstract measures of productivity difficult to extract much signal from, and this paper hasn’t shifted my opinion much on that - so many of these numbers are simply hard to make sense of. I will continue to prefer more direct measurements of construction costs, for reasons I mentioned previously:

I suspect cost indexes are reasonably accurate. They’re simple to construct, are based on fairly direct measurements, the folks that produce them have strong incentive to make them accurate (since their accuracy is something builders and developers are often paying for), and they’re mostly consistent both with each other and other data we’ve looked at

Thanks to Matt Clancy, Jeremy Neufeld, and Heidi Williams for feedback on this essay. All errors are my own.

[0] - One possible explanation is that “specialty contractor labor” is referring to labor from outside the construction sector. This would make the numbers make sense (half the value coming from construction labor, half from purchased materials, which roughly matches what you get from e.g. estimating guides), but Sveikauskas et al seem pretty clear that “specialty contractor labor” is counting common construction trades like electricians and plumbers.

The treatment of specialized-trade inputs, which seems both not-well-defined and non-intuitive, is a big red flag for me -- it seems like the resulting measures depend heavily on the in-house vs contracted practices of GCs over time, which is only loosely related to 'productivity.' That being said, the figure for cost of highway construction seems much easier to measure and unambiguously bad, even starting from 2003, so that might be a good place to start further exploration.

I also wonder if there has been a change in the distribution of the relative 'quality' of new construction -- in the sense of new housing that costs more or less than the area median. Affordable housing advocates claim that construction in cities is dominated by high-end developments (chasing higher margins), but I don't know 1) if that's true or 2) how that compares historically.

I doubt the problem is monocausal, but one cause not identified is the difference in regulatory compliance. It takes a lot more to meet codes and standards than it might have 50 years ago. The cause could actually be a net social good if we value more efficient buildings and better worker safety.