How Bell Labs Won Its First Nobel Prize

Bell Labs, as we’ve noted before, was for years America’s premier industrial research lab. Not only did Bell Labs invent much of the technology that powers the modern world — the transistor, the solar PV cell, the first communication satellite — but it made numerous scientific breakthroughs, accumulating more Nobel Prizes than any other industrial research lab.

I’m generally skeptical of efforts to create a “modern Bell Labs,” as I think much of what made Bell Labs work was historically contingent. But I nevertheless think there’s value in understanding what exactly made Bell Labs so good, and how we might apply those lessons to modern organizations.

One way of understanding what made Bell Labs tick is to look at its early history, before it became America’s premier industrial lab. To that end, let’s take a look at how Bell Labs won its first Nobel Prize.

The prize was awarded to physicist Clinton Davisson in 1937 for demonstrating the existence of electron diffraction — the fact that, in some circumstances, electrons act like waves rather than particles. This discovery was based on research done by Davisson that began in 1920, just a few years after Theodore Vail (the first general manager of AT&T) returned to the company and set it on a more technology-focused trajectory, and before Bell Labs as a formal organization even existed.

Clinton Davisson and Western Electric

Clinton Davisson was born in Illinois in 1881. While he displayed an aptitude for math and science from an early age, he had a somewhat fitful journey into physics. When Davisson graduated high school in 1902, he attended the University of Chicago, but after a year was forced to drop out due to lack of funds. One of his professors, Robert Millikan (who would later win the Nobel Prize for discovering the charge of the electron with his oil drop experiment), arranged for Davisson to work at Purdue University as an assistant instructor in physics. Davisson returned to University of Chicago later that year, only to leave again to work as a part-time instructor at Princeton. Davisson finally graduated from University of Chicago with his bachelors in 1908, and received his PhD from Princeton in 1911.

After graduating from Princeton, Davisson got a job as an instructor of physics at Carnegie Institute of Technology (today known as Carnegie Mellon). While at Carnegie, most of Davisson’s time was occupied by teaching; over the next six years he managed to perform a few experiments (one on X-rays reflected off of tungsten, another on the energy emitted by hydrogen spectral lines), but achieved no publishable results. Davisson’s only publications at Carnegie were one theoretical article (on Niels Bohr’s recently-invented model of the atom) and two short theoretical notes (on gravitation and electrical action, and a theoretical model of the electron). Including his work at Princeton, by 1917 Davisson had only published six papers.

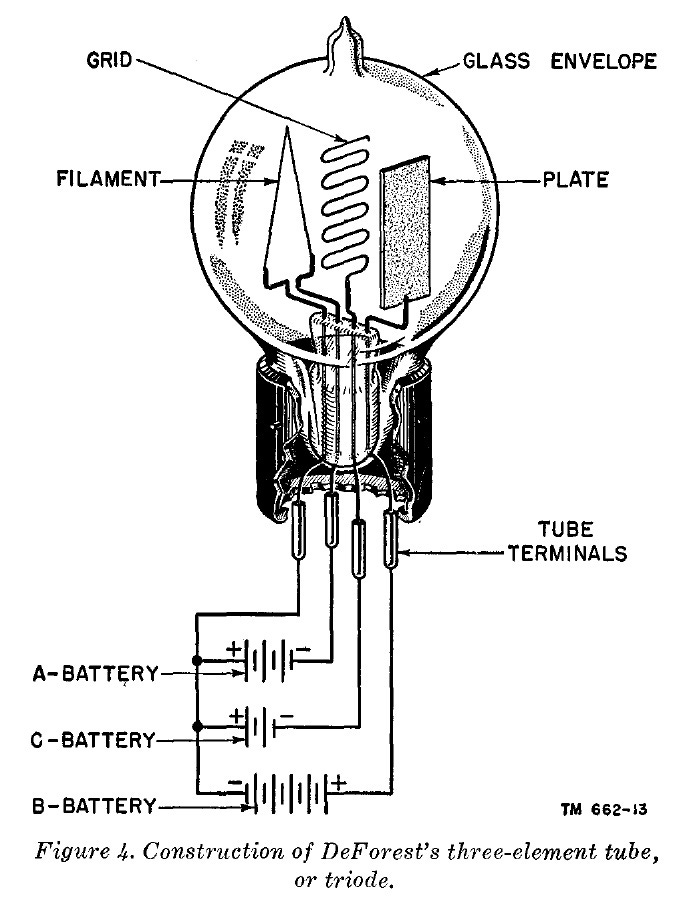

In 1917, Davisson took a summer job at Western Electric, the manufacturing arm of AT&T, to assist with manufacturing vacuum tubes for the military during WWI. At the time, vacuum tubes used a filament coated in platinum oxide, but platinum was in short supply due to the war; Davisson worked to help develop a nickel oxide coated filament. Davisson, who was mostly interested in scientific investigations rather than development work, was apparently not particularly thrilled with this assignment — Mervin Kelly, former president of Bell Labs, noted in a biography of Davisson that “the needs of the situation forced upon him somewhat of an engineering role for which he had little appetite” — but he nevertheless did it well. The temporary assignment soon became permanent, and by 1918 Davisson was in charge of four different groups of engineers at Western Electric, managing all aspects of the new nickel oxide filament’s development.

Following the end of the war, Davisson planned to return to Carnegie, where he had been offered a promotion to assistant professor. However, Davisson’s boss, Harold Arnold (who would become Bell Labs’ first director of research) asked Davisson to stay at Western Electric. Davisson had little to no interest in management, or in engineering-type work, though he had performed those tasks when they were required of him — his overwhelming interest was in scientific investigations, to achieve “complete and exact knowledge of the physical phenomena under study.” Arnold seems to have enticed Davisson to stay by offering him the opportunity to pursue fundamental scientific research at Western Electric, a rare occurrence at industrial labs at the time, and for most of his time at AT&T, Davisson would have the luxury of following his own research interests, aided by a small team of physicists and lab assistants.

Davisson, nickel, and electrons

Davisson’s first post-war assignment was to bombard vacuum tube filaments with positive ions, to see how it affected electron emissions. This research assignment was the product of a patent dispute over the vacuum tube between Western Electric and General Electric. The dispute began in 1915 when Harold Arnold filed a patent on an improved vacuum tube, to provoke an interference with an existing General Electric vacuum tube patent which Western Electric believed was illegitimate. The dispute, which took 16 years to resolve (it was ultimately decided in Western Electric’s favor by the Supreme Court in 1931), hinged on extremely technical aspects of vacuum tube operation, and whether certain improvements were novel enough to be patented. Because of the highly technical basis of the various patent claims, Arnold felt it was valuable to gain a better physical understanding of how, specifically, vacuum tubes behaved. To assist on this assignment, Davisson was joined by Lester Germer, a young physicist.

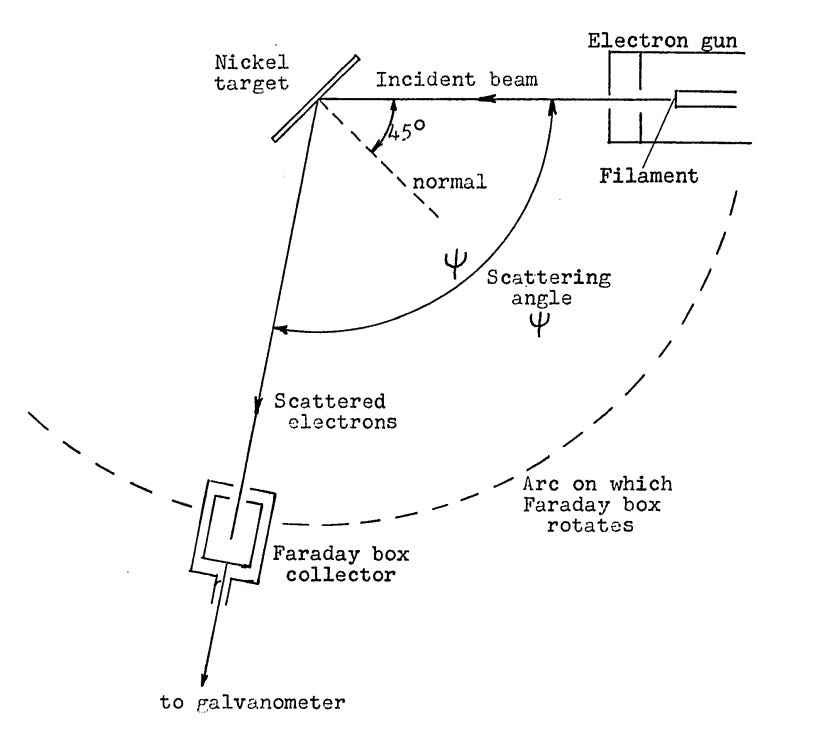

Ultimately, Davisson and Germer found that ion bombardment had virtually no impact on the electron emission behavior of tube filaments. After these ion bombardment experiments were concluded, Germer continued to work on studying the electron emission of filaments, while a new physicist, CH Kunsman (who had joined in June 1920) took over as Davisson’s primary collaborator. Davisson and Kunsman then began using their experimental apparatus to bombard vacuum tube grids and plates with electrons instead of positive ions. During these experiments, Davisson and Kunsman stumbled across an unexpected phenomenon: that some electrons bounced off their targets “elastically” (with roughly as much energy as they had collided with).

Davisson thought that these elastically scattered electrons might prove valuable as a research tool. Just a few years before, in 1911, a research team led by Ernest Rutherford had discovered that matter in an atom was concentrated in a tiny, dense “nucleus” at its center, by bombarding a thin gold foil with alpha particles (helium atoms shorn of their electrons) and observing how they were scattered. Davisson thought that a similar experiment, using elastically scattered electrons instead of alpha particles, might shed light on the electron structure of atoms. At the time it was generally agreed that the atomic nucleus was surrounded by electrons which inhabited discrete “shells” — specific orbits that electrons were allowed to occupy — but little was known about how those shells were arranged.

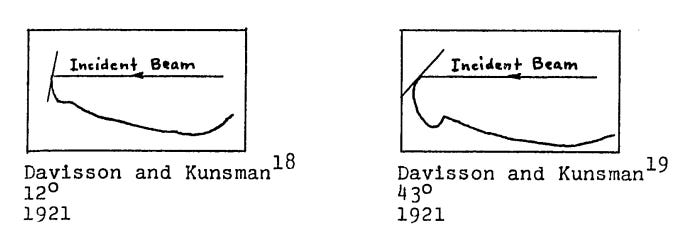

In 1921, Davisson and Kunsman began their experiments using elastically scattered electrons. By bombarding a piece of nickel with electrons, and recording the angles at which they bounced off, they hoped to learn about the structure of the electron shells surrounding the nickel atoms.

Initially, this line of research appeared promising. Davisson and Kunsman were able to develop a formula that related the scattering angle to a hypothesized structure of the electron shells (though they only made a qualitative comparison between their formula and their experimental results), and they published a short paper on their work later that year. The duo then continued this line of study with other metals, examining the scattering behavior of copper, aluminum, platinum, and magnesium, and publishing papers on their results in 1922 and 1923. However, these investigations ultimately failed to pan out, teaching them little about the behavior of atomic electron shells.

These disappointing outcomes apparently dulled the team’s enthusiasm for the electron scattering studies; when Kunsman departed Western Electric in November of 1923, the scattering experiments ceased.

Experimental serendipity

A breakthrough in this line of research came a little over a year later, following the return of Lester Germer, who had been on a leave of absence from Western Electric since 1923 due to health concerns and a nervous breakdown. When Germer returned in July of 1924, he resumed work on the electron scattering experiments.

These experiments had to be performed in a high vacuum, which required occasionally pumping air out of the large tube which contained the experimental apparatus. In early 1925, following one such repumping, a bottle of liquid air broke, cracking a charcoal “trap” that was used to help maintain the vacuum within the tube and covering the target — a highly polished piece of nickel — in a layer of solid oxide. Instead of simply replacing the target, Davisson and Germer decided to repair it, putting it through several rounds of intense heating and then removing a thin layer of material from the top.

Initially, when the scattering experiments were resumed with the bombardment of the repaired piece of nickel, the results were similar to what had been obtained prior to the accident. However, a few weeks later, Davisson and Germer began to observe electron scattering behavior which was very different from what had been seen prior to the accident and subsequent repair.

Upon close examination of the target piece of nickel, it was found that the repair had changed the character of its surface. Prior to the accident the nickel, like most pieces of metal, consisted of numerous tiny intersecting crystals — regular arrangements of atoms — which were fused together. But following the accident and repair, the number of crystal grains had been reduced by “several orders of magnitude”, resulting in just a few large crystal facets. Davisson had originally theorized that the atomic structure of the target — how the electron shells were arranged — would affect how electrons were scattered. But now it appeared that instead it was the crystal structure — how the individual atoms were arranged — which determined how electrons were scattered. Eventually, they found that the unexpected scattering results were due to the electrons bouncing off a single crystal of nickel.

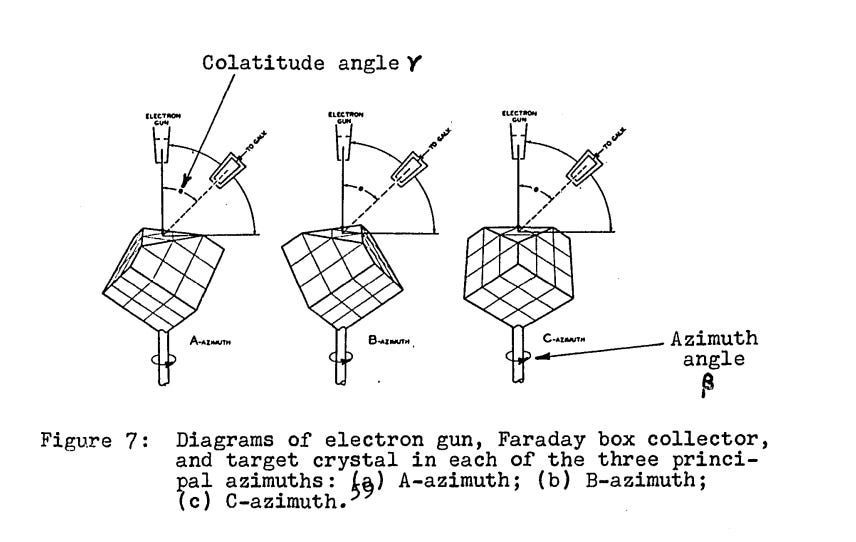

Pursuing this unexpected phenomena, Davisson and Germer eventually obtained a large single crystal of nickel (grown by a member of Bell Labs’ staff) to use as a target, and began to bombard it with electrons at different angles in 1926. However, the results appeared underwhelming. Davisson later noted that:

We were surprised and disappointed to find that it was indistinguishable from what would have been observed had the target been one of ordinary polycrystalline nickel— a simple curve with never a bump or spur from one end to the other. The Br and C-azimuths were explored with the same result.

A year of experimental effort had apparently led to nothing.

While these experiments were taking place, another notable event occurred. In 1925 the research activities of AT&T were reorganized and combined under a single roof: Bell Telephone Laboratories.

Wave particle duality

While Davisson, Kunsman and Germer were bouncing electrons off of various materials, a revolution was brewing in the field of physics. In 1905 Albert Einstein, to explain certain experimental results — namely, the way electrons were ejected from the surface of metal when exposed to light, known as the photoelectric effect — posited that light might impart energy via discrete packets, or “quanta”, of energy. Light, long thought to consist of waves, might in some cases behave like particles. This hypothesis was strengthened by experimental results from the American physicist Arthur Compton in 1922, who fired X-rays at various elements to see how they scattered. Compton found that the wavelengths of the X-rays increased when scattered by the target, which implied that the X-rays were transmitting their energy as a series of particle collisions.

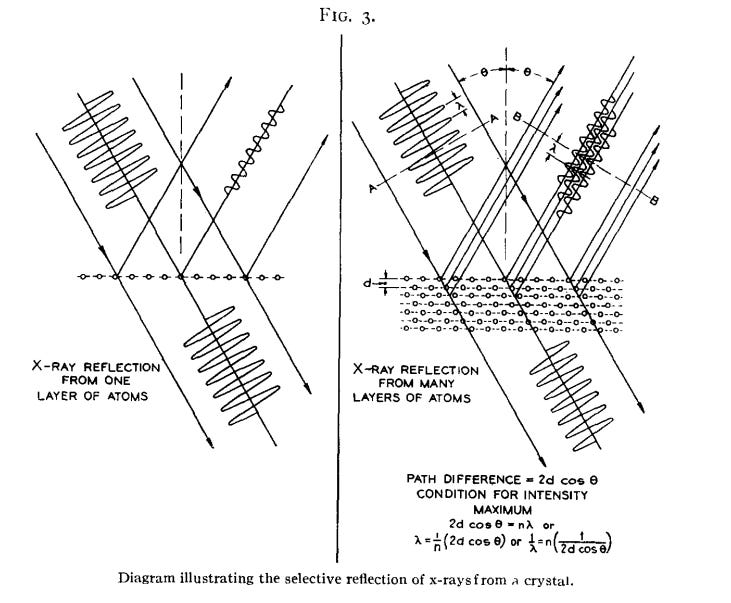

Around the time Compton was performing his experiments demonstrating that light waves sometimes acted like particles, a French physicist, Louis de Broglie, was hypothesizing that, conversely, particles of matter might sometimes act like waves. De Broglie advanced this theory in his 1924 doctoral thesis, and suggested that it could be experimentally verified by studying the scattering behavior of electrons by crystals. If electrons — atomic particles that carried negative charge — acted like waves, the regular structure of the crystal would act somewhat like a series of closely-spaced mirrors, reflecting the electrons in such a way to produce a tell-tale interference pattern (a phenomenon known as Bragg diffraction).

Most physicists did not think much of de Broglie’s theory, but some — including Einstein — found it compelling. One such supporter was German physicist Max Born, who discussed de Broglie’s ideas with his colleagues, including a young German graduate student named Walter Elsasser. Elsasser, who had seen Davisson and Kunsman’s 1923 paper on electron scattering, thought its results provided some evidence of de Broglie’s wave theory of matter, and published a short paper on this idea in 1925.

Elsasser then attempted to verify the theory with his own electron scattering experiments. But such experiments were difficult, as they required creating high-vacuum conditions that few labs were equipped for. After several months of attempts, Elsasser gave up (even though Einstein told him that he was “sitting on a gold mine.”) Several attempts by other physicists to show electron diffraction were either similarly abandoned due to technical difficulties, or produced inconclusive results.

Davisson, de Broglie and electron waves

In July of 1926, a few months after beginning the single crystal scattering experiments, Davisson went on vacation with his wife to England. While there, he attended a meeting of the British Association of the Advancement of Science, possibly so that he could classify the trip as “work related” and have it reimbursed by Bell Labs. At the meeting, Davisson saw a presentation by Max Born on the wave theory matter, which by now had been further developed by Erwin Schrödinger. Davisson at the time was unfamiliar with this theory, and was surprised to learn that his own previous electron scattering research was being used to support it. Davisson discussed his research with Born and others, and showed them unpublished data from his recent single crystal experiments that he had brought with him. Though the recent data didn’t appear to reveal much, the European physicists convinced Davisson that he nevertheless may be on the right track, and on his journey back to the US, Davisson began working his way through understanding Schrödinger’s papers.

When Davisson returned to the US, he and Germer first looked closely for the predicted electron diffraction pattern in their existing experimental data, but failed to find it. Undaunted, Davisson and Germer decided that a more “thorough search” was called for. They began by closely examining their experimental apparatus. Upon inspection, it was discovered that the crystal target had been rotated slightly, and that the opening in the Faraday box used to gather scattered electrons was shifted from where it was believed to be. When a correction was applied to previous experimental data to account for this, there appeared to be “extremely good” correspondence between the data and what the wave theory predicted.

Davisson and Germer then began a new series of single crystal electron scattering experiments, looking for beams of scattered electrons where the wave theory predicted they should be. On January 6th, 1927, they found what appeared to be confirmatory evidence, a telltale “peak” of electrons collected at a particular speed, which (per de Broglie’s wavelength formula) corresponded to a particular wavelength. This peak was not quite where the theory predicted it would be (the theory predicted one at 78 volts, while the peak was found, somewhat accidently, at 65 volts), but it was nevertheless evidence of a beam of diffracted electrons. Subsequent experiments found more peaks predicted by the theory.

Davisson and Germer published a paper with their results in Nature in April 1927. It included their electron scattering data, as well as scattering data collected when X-rays (which had known wavelengths and were known to diffract through crystals) were fired at the single crystal target. They found that if the wavelength of the electrons was calculated, and a (at the time unexplained) 0.7 adjustment factor was applied, the electron peaks corresponded with the peaks observed in the X-ray data. The paper concluded by noting that their results were “highly suggestive…of the ideas underlying the theory of wave mechanics”.

Davisson and Germer followed up this work with more experiments, looking for more predicted electron peaks and trying to explain peaks that were observed but not predicted by the theory, or that were predicted but not found. Many of these anomalous results were found to be caused by gas on the surface of the crystal or trapped within it. Others (such as the 0.7 adjustment factor) could be explained by the electrons refracting when they entered the crystal, altering the angle of their path through it. A follow-up paper, submitted to Physical Review in August, included even more predicted electron peaks, as well as explanations for several anomalous ones, though several other unexplained discrepancies between the theory and the data remained. Subsequent experiments by other physicists would later confirm Davisson and Germer’s results, that electrons were diffracted through crystals in accordance with the wave theory of matter.

Davisson and Germer followed up this work with experiments investigating whether electrons exhibited other wave-like behavior, including refraction, reflection and polarization, publishing 16 papers from 1928 to 1932, further strengthening the theory that electrons behaved as waves. Germer would continue studying electron diffraction into the 1940s, while Davisson shifted his efforts into “electron optics” — how differently shaped openings could act as lenses for electrons. In 1937, Clinton Davisson was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for the 1927 experiments which demonstrated the wave nature of the electron. (He shared the prize with G.P. Thomson who had, independently, also demonstrated the wave nature of the electron by scattering electrons through thin films of metal.)

Conclusion

Overall, what strikes me about this scientific discovery is how messy everything is. At a high level, the discovery seems like what we might expect for the scientific process: there’s an unexplained observation (Davisson and Germer’s surprising scattering results on the repaired piece of nickel), followed by a hypothesis that could explain those observations (de Broglie’s independently developed wave theory of matter), followed by an experiment to demonstrate the new hypothesis (Davisson and Germer’s 1927 scattering experiments). But when you zoom in, the path looks incredibly circuitous, full of false starts, disappointing results, and discrepancies between theory and experiment. Davisson’s research is kicked off by the unexpected discovery of elastically scattered electrons, but the resulting line of research to explore the electron structure of atoms is disappointing; so disappointing, in fact, that it’s abandoned for nearly a year. When it’s resumed, another unexpected event — the lab accident that results in a highly modified nickel target — leads to a new line of research, investigating the influence of crystal structure on electron scattering behavior. But this line of research also initially doesn’t seem very promising, yielding disappointing results at first. It’s only a third unplanned event — Davisson learning about the wave theory of matter from European physicists, which his earlier scattering experiments (done for totally different reasons!) seem to provide weak evidence for — that puts Davisson and Germer on the correct track.

Armed with this new theory, Davisson and Germer were eventually able to use their experimental apparatus to demonstrate that the data fit the theory’s prediction (electrons diffracting through a crystal), but this process was also messy. The data collected didn’t straightforwardly correspond with the theory’s predictions. The initial peak of electrons was found at 65 volts, not the predicted 78 volts, and the same experiments yielded a much larger peak at 30 volts that had to be strategically ignored. There were numerous other discrepancies from the theory: various beams of electrons where they shouldn’t be, a 0.7 “correction” factory that needed to be applied. Resolving these discrepancies took time and effort.

What’s more, the experiments were incredibly difficult to perform. Davisson and Germer succeeded in demonstrating electron diffraction where others had failed because their lab, unlike many others, had facilities for producing very high vacuums. But creating these conditions was difficult: the apparatus frequently broke, and slight misalignments in various pieces of equipment could, and did, distort the data.

Other takeaways from this discovery:

The importance of technology, and particularly new observational tools, for scientific discovery. The discovery couldn’t have been made without the ability to create a high vacuum, and Davisson’s line of research was kicked off by the discovery of elastically scattered electrons, which Davisson suspected could be used as a research tool.

The importance of serendipity and the unexpected for making scientific discoveries. The unexpected discovery of elastically scattered electrons, the accidental modification of the nickel target, Davisson’s chance exposure to the wave theory of matter, and the accidental discovery of the 65 volt electron peak all played a role in Davisson’s demonstration of electron diffraction.

It can be hard to predict how a line of research will evolve. Davisson began by studying the behavior of vacuum tube filaments, which led him to elastically scattered electron experiments, which led him to studying the effect of crystal structure of electron scattering, which (eventually) led him to electron diffraction. Except for the initial vacuum tube filament studies, none of these research directions was planned, and were only possible because Davisson had somewhat free rein to research what he liked.

It’s understandable why this sort of research is rare in a corporate setting. Davisson’s discovery was the product of a years-long line of research, which probably wasn’t particularly cheap. (It doesn’t seem to have taken a huge amount of personnel, but the equipment was almost certainly expensive, as evidenced by the fact that few other labs possessed it.) It didn’t result in any new products or services for AT&T. It was probably ultimately valuable to AT&T for the prestige factor of the Nobel Prize, but the prize wasn’t awarded until 17 years after the research began (and of course, most research efforts won’t be awarded Nobel Prizes). For an organization which needs to earn a profit, it’s not hard to see why funding this sort of work seems like a bad bet.

What does Davisson’s discovery tell us about Bell Labs? Davisson’s line of research was initially pursued because it was believed that there was value in a deep, physical understanding in how vacuum tubes and electronic devices behaved. This was apparently believed strongly enough that Western Electric allowed Davisson to pursue these sorts of scientific investigations, without worrying about whether they would result in practical applications, something that was (and is) rare in corporate settings.

It’s interesting to contrast this discovery with the discovery of the transistor. In some ways the efforts are similar. Both were research programs rooted in a deep understanding of electronic components, and both yielded Nobel Prizes in physics. But while Davisson’s research was pursued without regard to any particular practical application (and didn’t result in any, at least for AT&T), the transistor effort was part of a specific program to create a solid state amplifier. Bell Labs’ later ‘basic’ research efforts were much larger than those in the 1920s, but they also seem to have put more effort into nudging their researchers into working on important problems of practical significance.

Fascinating essay. I also find it interesting that at any one of these surprise points, Davisson could have chalked things up to faulty equipment (broken nickel target) or negative results (inconsistent peaks and correction factors) and moved on. Most people probably would have just replaced the nickel target and forgotten the weird results. But he followed the surprises.

Thanks. A really interesting story. Indeed the messiness of the process is striking, though as a (retired) experimental biologist, not too surprising. Another striking feature was Davisson's PERSISTENCE.