How Long Will a Home Last?

Plus: octagon houses, chart rooms, Soviet apartment blocks and truss-joist hybrids

Welcome to Construction Physics, a newsletter about the forces shaping the construction industry.

How long will a home last?

This is surprisingly difficult to answer. Most homes today (whether in multifamily buildings or single family houses) are built out of light framed wood, using balloon frame or platform frame construction. This system can potentially last for many years - there are plenty of examples of balloon framed houses from the 1800s still in use. But those could be unusually well constructed (either at the time or by modern standards), or the result of good luck, or had efforts to deliberately preserve them. As long as components are replaced whenever they wear out, and it’s not destroyed by fire or some other disaster, a house could theoretically exist indefinitely, Ship of Theseus style. Even the framing or the foundation can theoretically be replaced if the will (and money) exists to do it. Over time, an old house may accumulate enough cultural, historic, or artistic value that it’s worth it to keep maintaining it.

We shouldn’t expect this fate for most houses though. The National Register of Historic Places lists over a million historic properties in the US (not all of which are homes), but there are nearly 9 million homes over 100 years old in the US.

A better question might be how long is a home likely to last - what’s a home's life expectancy? This is also hard to answer directly. Most measurements of building lifespan provide estimates for individual components (which wear out at different rates), not the house itself. The National Association of Certified Home Inspectors gives an estimated lower bound of 100+ years for the timber frame and concrete foundation (which nearly every home will have). The National Association of Homebuilders helpfully says the foundation and framing will last “a lifetime”. So we’ll need to dig deeper.

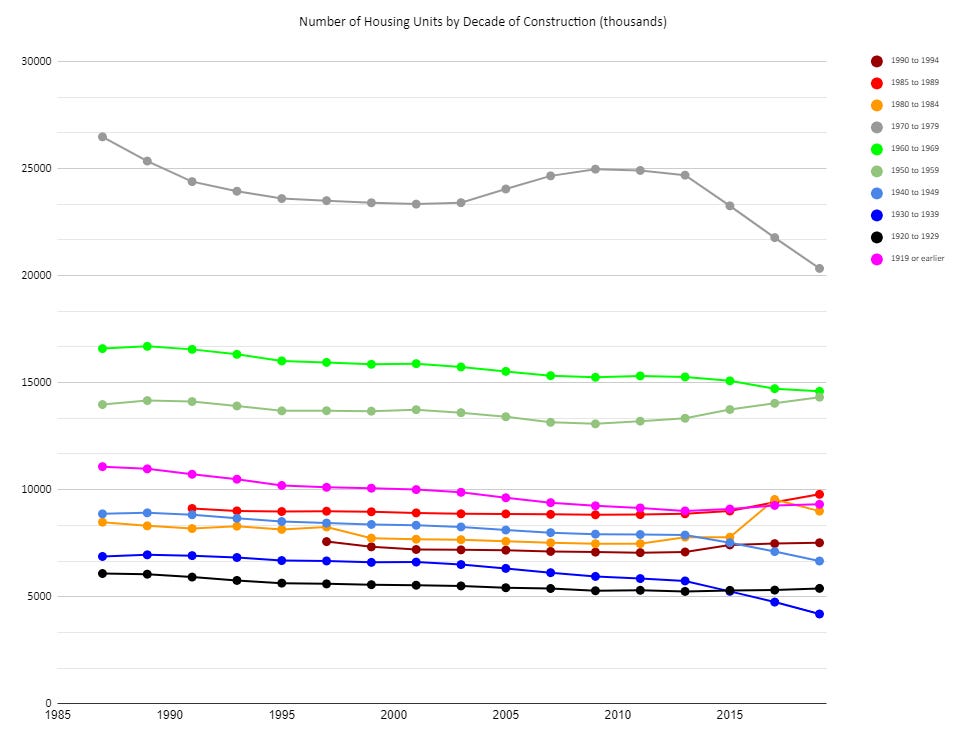

The best source of data on the age of the US housing stock is the American Housing Survey, which is performed every 2 years on a sample of several thousand homes in different housing markets around the country. One of the factors they measure is decade of construction, which lets us see how the number of homes constructed in a given decade changes over time. Below is a graph summarizing this year of construction for all homes (single family and multifamily), starting in 1987.

Unfortunately, the data is quite noisy, and even after smoothing, some strange trends remain. Once a decade is over the number of homes built should only ever stay the same or decrease , but in some cases we see this increasing over time[1]. According to AHS data, there are more homes built in the 1950s in 2019 than there were in 1987, which seems unlikely.

Homes built in the 70s show a similar strange trend, at first decreasing sharply (a pattern no other decade shows), then increasing, then another sharp decrease. So to the extent we can rely on them at all, we’ll need to treat these numbers with a large grain of salt.

Using these numbers to calculate an average home age gets us a value that’s steadily increasing over time:

For completeness, I pulled the average home age for the years prior to 1970 from Historical Statistics of the United States Colonial Times to 1970. We can see that the average age is steadily increasing, and has never been as high as it is currently. An average age that increases this fast (around 0.3 years per year since 1983) suggests few homes are leaving the housing stock, and the ones that are being removed don’t substantially skew older.

This is another effect of a stagnant building industry - there’s no impetus to replace old homes if new ones aren’t substantially better.

Other than generally trending downward over time, we don’t really see any patterns in the number of homes per decade of construction that would imply anything other than a simple linear decay rate. It appears roughly that homes built after 1980 are very unlikely to leave the housing stock, and homes built prior to that leave the housing stock at a rate ranging from 0.4% to 1.7% a year.

Crucially, this rate of decay does not appear to be related to house age. Homes built before 1920 are no more likely to be removed from the housing stock than homes built in the 1970s:

This makes a certain amount of sense. All else being equal, a new home is likely to be built in an area that needs it, and for its first 30-40 years of life is unlikely to encounter problems seriously enough to warrant removing it. The only removals should be from the base rate of destruction by fire, flood, or other disasters.

But as it ages, maintenance costs continue to increase, and economic or cultural conditions may no longer warrant spending the money. Maybe the area has gone into economic decline and is losing population, or the size of the home doesn’t match what people want anymore[2].

Using this simplified model (30-40 years of essentially no losses, followed by a constant decay rate), we get an expected house lifespan of 100-300 years.

There were around 27.5 million homes in 1920, around 9 million, or 33% of which still exist. This is less than the bottom of our lifespan range implies. But the early 20th century saw the widespread adoption of building technologies such as electricity and indoor plumbing, which are difficult (ie: expensive) to retrofit into an existing house. Without a similar change in building technology, we should see houses in use for longer today.

One question is if, despite using essentially the same framing system as older houses, newer construction techniques will reduce modern homes lifespan compared to older homes. Engineered products such as LVL and I-Joists are relatively recent inventions, and are increasingly being used in home construction. One product in particular is Oriented Strand Board, which since its introduction in the 1970s has become the standard product for sheathing wood walls and floors, and only has a projected lifespan of 60 years[3].

[1] - It is possible for the homes built in a given decade to increase, either by a building moving from non-residential to residential, or by dividing a building into a larger number of housing units, but these should be small numbers.

[2] - Average home size increased 1000 square feet between 1970 and today.

[3] - Though like with anything, it varies. Some manufacturers give a lifetime warranty for their OSB sheathing.

Elsewhere

Octagon-shaped house for sale in New York. These octagon houses were popular for a brief period of time in the mid 1800s, after a book was published extolling their virtues. The not-unreasonable theory was that a house closer to a sphere, which encloses the maximum volume using the least area, would be more efficient to build. 100 years later Buckminster Fuller would pursue similar ideas with his Dymaxion House.

Triforce offers a hybrid wood truss/I-Joist that’s framed without side plates, instead using finger joints in the webs and flanges. The intent seems to combine the best features of wood trusses and I-joists: a truss for ease of running MEP, with 2 feet of I-Joist on the end for field trimmability. It’s hard to imagine these being a low-cost solution though.

Khrushchyovkas are 5-story prefab apartment buildings that were built by the thousands during the 60s in the former Soviet Union. At its peak, 60 million people were housed in Khrushchyovkas, making these an example of true mass-produced construction. Built using precast concrete panels, they could be assembled in as little as two weeks, and were all more or less identical. Though intended to last just 25 years (just long enough for the glorious Communist future to arrive), as of 2017 there were still thousands of them in existence.

70 years before the invention of PowerPoint, DuPont built a room for giving presentations that used physical charts moved by a monorail system built into the ceiling.

Thanks for subscribing to Construction Physics. Feel free to forward this to anyone who might be interested, or to email me at briancpotter@gmail.com with thoughts or comments.

Staggering increase in U.S. home size! And of the 970,000 single-family homes completed in 2021, 444,000 had four bedrooms or more, and 320,000 had three or more bathrooms.

https://www.census.gov/construction/chars/highlights.html

Also thanks re LVL, I-joists and oriented strand boards, and the DuPont room.

(The average age increasing) is another effect of a stagnant building industry - there’s no impetus to replace old homes if new ones aren’t substantially better

*Or if substantially better and bigger is illegal!