How Much Safer has Construction Gotten?

When talking about (the lack of) construction productivity growth, or the fact that we used to build things much faster than we do today, commentators frequently mention the safety of the construction workers. On this view, construction speed/efficiency and worker risk are a tradeoff, and as a society (for better or for worse) we’ve opted to reduce risk, making construction work safer at the cost of making it slower and less efficient.

Does safety make sense as an explanation for the sluggish growth of construction productivity? How much safer has construction really gotten? Let’s take a look.

Construction used to be incredibly dangerous

By the end of the 19th century, what’s sometimes called the second industrial revolution had made US industry incredibly productive. But it had also made working conditions more dangerous. Industrialization meant that work was increasingly done near machines that were moving at high speeds, exerting large forces, or carrying materials under intense heat and pressure. The consequences of any misstep or equipment failure were high. Rotating shafts could catch on workers’ clothing. High-pressure boilers and pressure vessels could explode. Electrical equipment could cause deadly shocks.

In blast furnaces, for instance, the practice of “hard driving” – forcing more air into the furnace to increase its output – had made explosions much more likely. One steel executive noted in 1915 that “I remember the time when the operation of the blast furnace was not a hazardous occupation and likewise I have seen it become a very hazardous occupation.” Similarly, while the puddling process for making iron required back-breaking physical labor, it wasn’t especially dangerous – in 1910 there were no recorded fatalities out of a total of 1300 puddlers working in the US. The Bessemer process for making steel, on the other hand, “was accompanied by great sacrifice of life and limb,” and in 1910 it had the highest fatality rate of any portion of the steel industry.

One source estimates 25,000 total US workplace fatalities in 1908 (Aldrich 1997). Another 1913 estimate gave 23,000 deaths against 38 million workers. Per capita, this is about 61 deaths per 100,000 workers, roughly 17 times the rate of workplace fatalities we have today.

Even for its time, the early 20th century US work environment was especially dangerous. American coal and railroad workers, for instance, had death rates 2 to 3 times as high as their British counterparts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

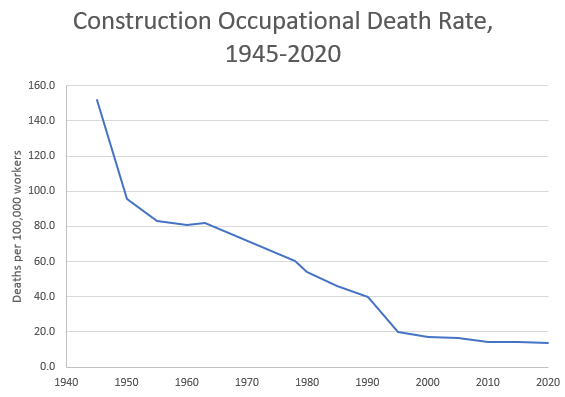

In a world of dangerous work, construction was one of the most dangerous industries of all. By the 1930s and early 1940s the occupational death rate for all US workers had fallen to around 36-37 per 100,000 workers. At the same time, the death rate in construction was around 150-200 deaths per 100,000 workers, roughly five times as high. Death rates in construction were much higher than in manufacturing (~20 per 100,000 workers) and agriculture (~60 per 100,000 workers). By comparison, the death rate of US troops in Afghanistan in 2010 was about 500 per 100,000 troops. By the mid-20th century, the only industry sector more dangerous than construction was mining, which had a death rate roughly 50% higher than construction. [0]

We see something similar if we look at injuries. In 1958 the rate of disabling injuries in construction was 3 times as high as the manufacturing rate, and almost 5 times as high as the overall worker rate.

The danger in different sectors of construction varied, with some much more dangerous than average. Ironworker death rates, for instance, were incredibly high. In 1912, the International Association of Bridge and Structural Ironworkers had 109 deaths due to accidents, out of a membership of 10,928 – a death rate of 1000 per 100,000 workers, twice the death rate of US soldiers in Afghanistan in 2010. By the mid 20th century this seems to have decreased significantly, but ironworkers still had an occupational death rate three times as high as construction overall.

Tunnel work was also especially dangerous – tunnel workers had a rate of disabling injury higher than any other sector of heavy construction, and nearly twice as high as construction overall. This was partly due to the confined nature of tunnel construction work, which made it subject to unique risks. In the 1936 Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster, 476 out of 3000 tunnel workers died after contracting silicosis from breathing in silica dust. And during the construction of the Hoover Dam, 37 tunnel workers died from inhaling carbon monoxide released from idling gasoline engines.

If you look at footage of early 20th century construction, it’s not hard to find an abundance of shockingly dangerous activities. In footage of the Empire State Building’s construction, for instance, we can see 4 workers grabbing onto a crane hook and riding it down to the ground. Workers routinely shimmy up columns or walk on narrow ledges without any sort of fall protection. Unsurprisingly, in early 20th century New York 25 to 33% of the deaths in construction were due to falls, with another 10-15% due to falling objects. [1]

Increasing safety

Over the course of the 20th century, construction steadily got safer.

Between 1940 and 2023, the occupational death rate in construction declined from 150-200 per 100,000 workers to 13-15 per 100,000 workers, or more than 90%.

For ironworkers, the death rate went from around 250-300 per 100,000 workers in the late 1940s to 27 per 100,000 today. [2]

Tracking trends in construction injuries is harder, due to data consistency issues. A death is a death, but what sort of injury counts as “severe,” or “disabling,” or is even worth reporting is likely to change over time. [3] But we seem to see a similar trend there. Looking at BLS Occupational Injuries and Illnesses data, between the 1970s and 2020s the injury rate per 100 workers declined from 15 to 2.5.

Less obviously dangerous fields of construction exhibit a similar trend. Homebuilding, for instance, seems like it would be on the safer end of construction work: less work being done at dangerous heights, fewer pieces of heavy machinery, and less heavy masses being moved, but it’s also gotten significantly safer. Over 25 years the death rate in single family home construction declined by roughly 50% (though 2001-2004 is doing the lion’s share of the work here).

Likewise, declines in injury rates in single family home construction have mirrored those in construction overall. Between 1994 and 2020 reported injuries in residential construction declined by 72%, compared to 79% in construction overall. [4]

Construction still remains one of the most dangerous industries, but it’s improved significantly over time.

Source of safety improvements

Improvements in US construction safety were due to a multitude of factors, and part of a much broader trend of improving workplace safety that took place over the 20th century.

The most significant early step was the passage of workers compensation laws, which compensated workers in the event of an injury, increasing the costs to employers if workers were injured (Aldrich 1997). Prior to workers comp laws, a worker or his family would have to sue his employer for damages and prove negligence in the event of an injury or death. Wisconsin passed the first state workers comp law in 1911, and by 1921 most states had workers compensation programs.

The subsequent rising costs of worker injuries and deaths caused employers to focus more on workplace safety. According to Mark Aldrich, historian and former OSHA economist, “Companies began to guard machines and power sources while machinery makers developed safer designs. Managers began to look for hidden dangers at work, and to require that workers wear hard hats and safety glasses.” Associations and trade journals for safety engineering, such as the American Society of Safety Professionals, began to appear.

At the same time, various government agencies tasked with monitoring and enforcing safety and working standards were formed. The Bureau of Mines was established in 1910 following a series of mining disasters that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of workers. The Department of Labor, mandated to improve working conditions, formed in 1913. That same year, a consortium of companies formed the National Safety Council. During WWI, Congress created a Working Conditions Service to “inspect war production sites, advise companies on reducing hazards, and help states develop and enforce safety and health standards.”

In 1934, the Department of Labor established a Division of Labor Standards, which would later become the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), to “promote worker safety and health.” The 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which legalized collective bargaining, allowed trade unions to advocate for worker safety.

Following WWII, the scale of government intervention in addressing social problems, including worker safety, dramatically increased. From “The Beginning and End of the Rise of American Tort Law”:

Between 1964 and 1968, Congress produced new legislation at an historic rate. The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, prohibiting discrimination in employment and public accommodations; it was followed by such measures as the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Serious problems of poverty persisting in America were discovered, leading to the declaration of a war on poverty, a war that was implemented along several fronts. The deterioration of our cities was finally recognized; with high hopes, a new Department of Housing and Urban Development was created not only to coordinate existing federal programs but also to develop for the first time a federal urban policy. A Department of Transportation was also established and charged with the responsibility of thinking through a national transportation policy, one that could be ‘comprehensive’ in that it would include all transportation modes and would take account of social and environmental perspectives that had previously been ignored by the technicians running such agencies as the Federal Aviation Administration and the Bureau of Public Roads.

The establishment of new programs continued into the Nixon administration. In 1970, it was President Nixon who, without evident discomfort, signed the Clean Air Act Amendments and Occupational Safety and Health Act. Indeed, more new federal agencies were created during the Nixon administration than had been created during the administration of Franklin Roosevelt.

In addition to OSHA and environmental protection laws, this era also saw the creation of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

OSHA in particular dramatically changed the landscape of workplace safety, and is sometimes viewed as “the culmination of 60 or more years of effort towards a safe and hazard-free workplace.”

Until 1971, state agencies bore the prime public responsibility for reducing the annual toll of several thousand work fatalities, approximately two million disabling injuries, and an unknown number of occupational diseases…[OSHA] transformed the enforcement of safety and health standards from an overwhelmingly state function to a predominantly federal one. Under OSHA, fines for violations, which had been rare, became commonplace. Penalties were facilitated by the act’s substitution of a simple civil procedure for the lengthy and costly criminal trials which states had relied upon. The procedural changes reflected a shift in enforcement philosophy; formerly, state agencies had seen their role as consultative - to educate employers, not to alter their incentives. Under the OSH Act, the goal of obtaining compliance became paramount…

Today, OSHA remains the primary vehicle of workplace safety enforcement: OSHA inspectors conduct over 20,000 workplace inspections annually, and hand out hundreds of millions of dollars in fines for safety violations.

Construction vs other industries

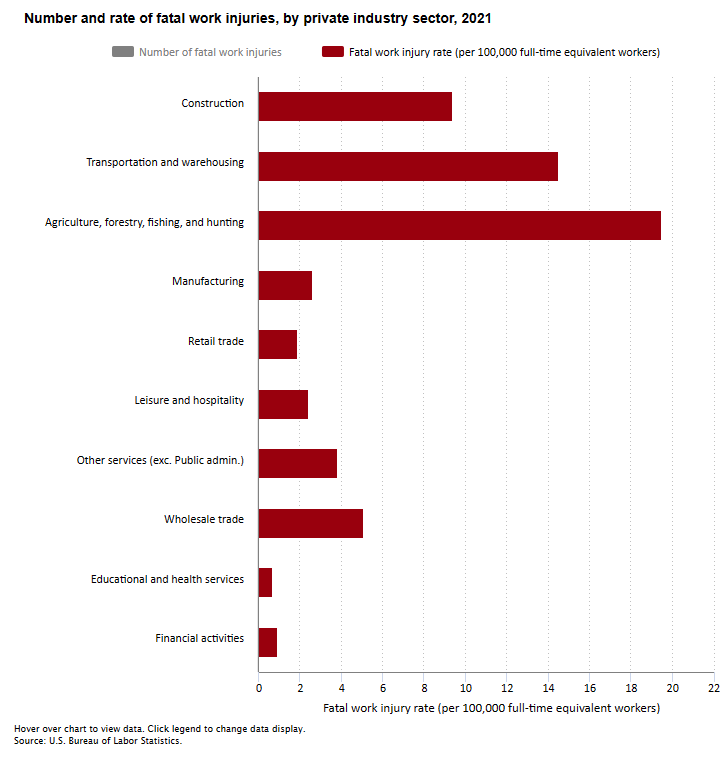

One potential challenge to the “speed/efficiency vs risk” tradeoff as an explanation of sluggish construction productivity is that, as with increasing regulation, other industries have also gotten significantly safer over time. The overall occupational death rate declined from 60 per 100,000 in the 1910s to around 3 per 100,000 today. Occupational injury rates have likewise declined overall:

As with regulation, increased safety only makes sense as an explanation for low construction productivity if safety requirements have a greater impact on construction than on other industries. Is this the case?

Surprisingly (to me), it seems like it is. For one, construction seems to have gotten safer faster than other industries. Here are occupational death rates for construction, agriculture, and manufacturing since 1945:

In 1945, construction was 2.5x as deadly as agriculture, and 5.6x as deadly as manufacturing. Today, those numbers are 0.64x and 5x respectively. Death rates in construction declined 3.2% per year on average in construction, compared to 2.6% per year in manufacturing and 1.4% per year in agriculture.

We see a similar trend if we look at injury rates.

Over a 44-year period, construction went from having a higher rate of recordable injuries than manufacturing and agriculture to a lower one. Occupational injury rates have declined around 4% per year in construction, compared to 3.2% per year in manufacturing and 1.9% per year in agriculture. (It’s also suggestive that this is the inverse of the industries which have seen the greatest productivity gains.)

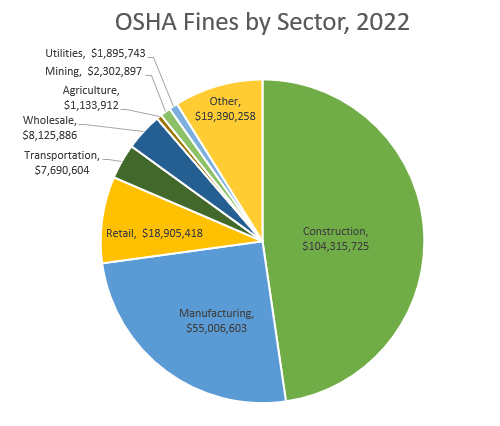

Additionally, enforcement of safety regulations seems to be a much greater burden on construction than on other sectors. In 2022, for instance, OSHA fines in the construction sector were $103 million dollars, compared to $1.1 million in agriculture and $55 million in manufacturing. The construction sector makes up 4% of US GDP, 3% of US employees, and 19% of occupational deaths, but is responsible for nearly 50% of OSHA fines. Of the 10 most cited OSHA standards violations, 5 of them are specific to construction.

This shouldn’t necessarily be surprising. It’s much easier to observe safety violations on a construction site than in other types of work. Construction takes place out in the open, and is visible from the street – OSHA inspectors can (and do) spot violations by simply driving by and taking pictures.

The temporary nature of construction also means that safety precautions often require proportionally more effort than in other industries. For instance, fall protection devices (such as guardrails) that only need to be installed once in a factory need to be newly installed (and then uninstalled) on every new building that goes up. And depending on the type of construction, guardrails or other protection devices might be installed over and over again in the same building, as the exposed edge of the building moves over the course of construction.

Safety as an explanation for low productivity.

Putting aside for the moment any sort of cost-benefit analysis of this increase in safety, does it make sense as an explanation for construction’s sluggish productivity growth?

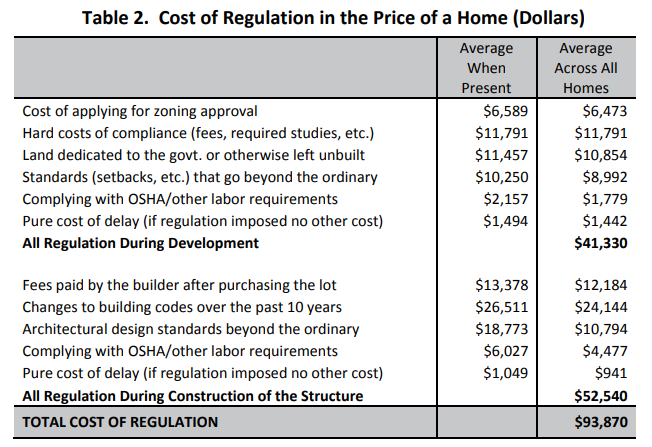

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that it’s at least part of the answer. But I suspect it’s only a part, perhaps not a particularly large one. For one, as we saw previously, homebuilders don’t seem to think the burdens of OSHA and other safety regulations are all that high. Complying with OSHA is the second lowest category of perceived jobsite regulatory costs, after “delay” [5]:

And if you watch construction crews working on single family homes, you often see very little in the way of safety precautions that might slow down work. Workers are seldom tied off when working next to a leading edge, for instance (in my experience at least).

So I don’t think it works as an explanation on its own. But it seems like part of the story.

[0] - Data source is the 1944 US statistical abstract for number of deaths and agriculture employment, and FRED for construction and manufacturing employment. Estimate for overall occupational death rate matches the number given by the National Safety Council for 1933, see here. Note that for most of these estimates there’s a great deal of variation. Employment estimates for agriculture, for instance, vary significantly between the statistical abstract and other sources such as here and here.

[1] - Data from 1914 here. Data from the mid-1920s here

[2] - There’s some slight inconsistencies in the numbers here. Ironworker deaths are from a 1948 survey of over 16,000 contracting companies, which gives a death rate for ironworkers as 3 times higher than the overall rate. But using their numbers (1.2 deaths per million worker hours) gets around 260 per 100,000, which is closer to 2.5x the overall death rate.

[3] - There are, in general, lots of data consistency issues with measuring safety. Changes in reporting methodology or organizations doing the recording will result in huge shifts in injury and even death rates. You see, for instance, a huge change in death rates across all industries when the statistical abstract switched from National Safety Council estimates to Census estimates.

[4] - See here for BLS data.

[5] - As a reminder, single family homebuilding seems to show similar productivity issues as the rest of the construction sector.

I apprenticed with the Carpenters' Union just after the establishment of OSHA, in 1971. Most of my work was off the ground, forming large concrete structures and building scaffolding for other crafts to work safely off the ground. That first year OSHA implemented regs requiring us to be tied off to safety lines at all times when we were more than thirty feet off the ground. We resisted because it felt like complying slowed us down too much. My attitude changed when I returned to work eighteen months after shattering my right leg in a twenty-five foot fall. While I had learned patience, it was clear that safety came at the cost of productivity.

I think your overall conclusion is correct, but it is worth analogizing the struggles in construction safety with the struggles in construction automation, because they come from the same source.

It is easier to identify and mitigate safety issues in manufacturing processes for the same reason that it's possible to automate them: we have near-absolute control over the built environment in which they take place. We can add safety features to machinery, including shielding rotary assemblies and driveshafts from human contact, providing climate control, incorporating hand shields and reducing access around sharp objects, etc. We can train workers on processes that will be the same, day in and day out, down to the literal motion of their limbs around a piece of machinery.

These things often do mildly impact productivity relative to the baseline of no safety features or training (sewing machines are an emblematic case), but because they're often introduced simultaneously to other machinery and process improvements and because they reduce disruption, downtime, and turnover, they are only a small drag on productivity.

Moreover, safety equipment, by its nature, is most cumbersome when being moved, installed, or uninstalled. Thus it mainly impacts maintenance in factories, not production. But safety equipment on construction sites is *always* being moved and reinstalled as part of routine operations, so the impact is worse because the nature of site work makes safety measures more routinely invasive.

In addition, because we already struggle to implement any kind of productivity-enhancing automation, safety improvements are arriving on their own, unaccompanied by the sort of broader process and equipment improvements which would mask their impact. When industrial sewing machines began introducing needle guards, for example, they were simultaneously pioneering reversible functions and computer-aided stitching, so the slight slowdown that most experienced seamstresses will admit to seeing with a needle guard was hidden in the wash.

Fall protection for steel erectors, meanwhile, came alone, with no such productivity advances to mitigate it.

Overall I agree that safety practices are a drag on productivity rather than the main determining factor, but they are more challenging for the construction sector for the same reason that automation is more challenging.