How NEPA Works

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is a piece of federal environmental legislation that was passed in 1969 towards the beginning of an “eternal September” of environmental laws, and is often called the “magna carta” of environmental laws because of how influential it has been in shaping environmental policy. Not only does NEPA significantly influence federal government actions, but the law has served as a template that has been widely copied, both by state governments (in the form of “little NEPAs” such as California’s CEQA), and by other countries.

NEPA is the law that requires federal agencies to produce an environmental impact statement for any actions likely to have significant effects on the environment. These statements (which can be thousands of pages long and take years to prepare, and must be completed before the project can start), along with the broader perception that the NEPA process is slow and unwieldy, has made NEPA the frequent target of criticism and reform efforts.

Because NEPA impacts potentially every federal government action, in potentially very large ways, it’s worth understanding how NEPA works.

NEPA origins

NEPA evolved in a somewhat idiosyncratic fashion - it was originally intended as a sweeping environmental reform that would create a new policy of federal environmental stewardship:

the statute announces ‘the continuing policy of the Federal Government’ that federal agencies should ‘use all practicable means, consistent with other essential considerations of national policy, to improve and coordinate Federal plans, functions, programs, and resources’ to achieve such key environmental objectives as intergenerational trusteeship, provision safe and healthful surroundings, beneficial use of the environment, preservation of cultural and natural heritage, and protection of renewable resources.

But after NEPA was passed, these broad, sweeping reforms ended up amounting to little - courts found the provisions were too vague to be enforced, and they were largely ignored by federal agencies.

However, late in the process of drafting NEPA, a seemingly minor provision was added that required agencies to produce a “detailed statement” of the environmental impacts of any major federal action. This provision was a much clearer requirement that the courts enforced vigorously:

Mandatory procedures were something courts could and would enforce, especially under the command of unambiguous statutory terms like ‘all’, ‘shall’, ‘every’, and ‘detailed statement’. The threat of judicial enforcement, in turn, prompted agencies to be attentive to procedural detail, lest important agency actions be held up by litigation and injunction. Procedure soon overtook substance, transforming NEPA into what has become, in practice, almost purely a procedural statute.

The years immediately following the passage of NEPA resulted in a flurry of litigation as courts determined exactly what was required of the “detailed statement” NEPA mandated. To clarify what NEPA compliance required, the Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ), an executive branch organization created by NEPA and charged with overseeing its implementation, issued a series of guidelines in 1971. In 1978, these guidelines became regulation, creating the “modern” NEPA process we have today.

The NEPA process

NEPA as it exists today has largely become a procedural requirement - NEPA doesn’t mandate a particular outcome, or that the government places a particular weight on environmental considerations [0]. It simply requires that the government consider the environmental impact of its actions, and that it inform the public of those considerations. NEPA doesn’t prevent negative environmental impacts, so long as those impacts have been properly documented and the agency has taken a “hard look” at them - as one agency official described it, “I like to say you can pave over paradise with a NEPA document.”

More specifically, NEPA requires that a “detailed statement” be produced describing any significant environmental impacts of “major” federal actions. “Major federal action” might be anything from:

A new policy or procedure (such as the Forest Service changing its land management policy)

A new project (such as the Department of Energy constructing the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository)

Directing federal dollars (such as the Federal Highway Administration funding new highway construction)

Issuing a license or permit (such as the FAA issuing a launch license for SpaceX’s Boca Chica facility)

Or anything else that could possibly have significant environmental impacts. In practice, little effort seems to be placed on determining whether an action qualifies as “major”, and anything that might have significant environmental effects in practice must be NEPA compliant.

(There are also a small number of federal actions that are excluded from NEPA compliance at all. These include emergency actions that must be taken quickly.)

Determining whether a detailed statement is required has evolved into a tiered system of NEPA analysis. (This tiered system is not in the text of NEPA itself, but is the result of case law and the 1978 CEQ regulations.)

At the bottom, you have categorical exclusions (CEs.) These are actions that by their very nature have been determined to not have a major impact on the environment. For example, the FAA has determined that the acquisition of snow removal equipment can be categorically excluded, and the Bureau of Land Management has determined that “activities that are educational, informational, or advisory” can be categorically excluded. The vast majority of federal agency actions will generally fall under a categorical exclusion.

Categorical exclusions require the least amount of effort to complete, in some cases just requiring a form to be completed and signed (though as we’ll see, this can vary significantly by agency.) However, an action must fall under an approved class of action to be a CE, and adding a new type of excluded action can in fact be a significant effort, involving researching of past projects, a period of public commentary for the proposed exclusion, and approval by the CEQ.

Categorical exclusions are also sometimes added via legislative action. The Energy Policy Act of 2005, for instance, created several categories of categorical exclusion for certain oil and gas actions.

Originally few actions were classified as CEs, but as agencies have done more projects and gained a better sense of what projects will and won’t have major environmental impacts, more category exclusions have been added.

If an action can’t be categorically excluded, the next step for NEPA compliance is typically to figure out if the action will have “significant” environmental effects or not. If it’s unclear, an environmental assessment (EA) is performed, which is intended to be a high-level look at the proposed action to determine if the environmental impacts cross the “threshold of significance” and thus require a full environmental impact statement. If the EA finds no significant impacts, it issues a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI.)

EAs are generally more effort than categorical exclusions, though they also can vary significantly in the amount of effort required to create them.

If the EA concludes that the proposed action will have significant impacts, the “detailed statement,” known as an environmental impact statement (EIS) is produced. An EIS describes the proposed action, the likely environmental impacts of that action, alternatives to taking the action (typically including ‘no action’), and plans for soliciting feedback from the public.

EISs have become long, involved analyses that take years to complete and are often thousands of pages in length. For instance, the most current EIS available on the EPA’s database (for a Forest Service forest restoration plan) comes in at 1294 pages (including appendices), and took over 6 years to complete. In the late 1980s, there was a minor government scandal when the Department of Energy spent $1.4 million printing and mailing 17,000 copies of the 8,000-page EIS for the Superconducting Supercollider (the statements weighed a combined 221 tons.)

Because an EIS is so time consuming and expensive to prepare, procedures have evolved that let agencies avoid doing them. One popular method is the “mitigated FONSI” - if an environmental assessment determines that a federal action is likely to have significant impacts, the agency can include mitigation measures that would bring the net impact below the threshold of significance, and not trigger the EIS requirement. For instance, for the proposed construction of a cellulosic biorefinery on wetlands, the Department of Energy was able to achieve a mitigated FONSI by (among other things) purchasing “wetland credits” from a “wetland mitigation bank.” More recently, the FAA required SpaceX to undertake 75 mitigation measures as part of a mitigated FONSI for its Boca Chica launch site license (these ranged from periodic water spraying to control particulates and fugitive dust, issuing notices to personnel regarding lighting during sea turtle nesting season, and preparing a report on the historic events of the Mexican War that took place in the area.)

NEPA agency by agency

One challenge with understanding NEPA is that there’s a great deal of variation from agency to agency, both in the size and scope of their NEPA efforts and how they structure their NEPA procedures.

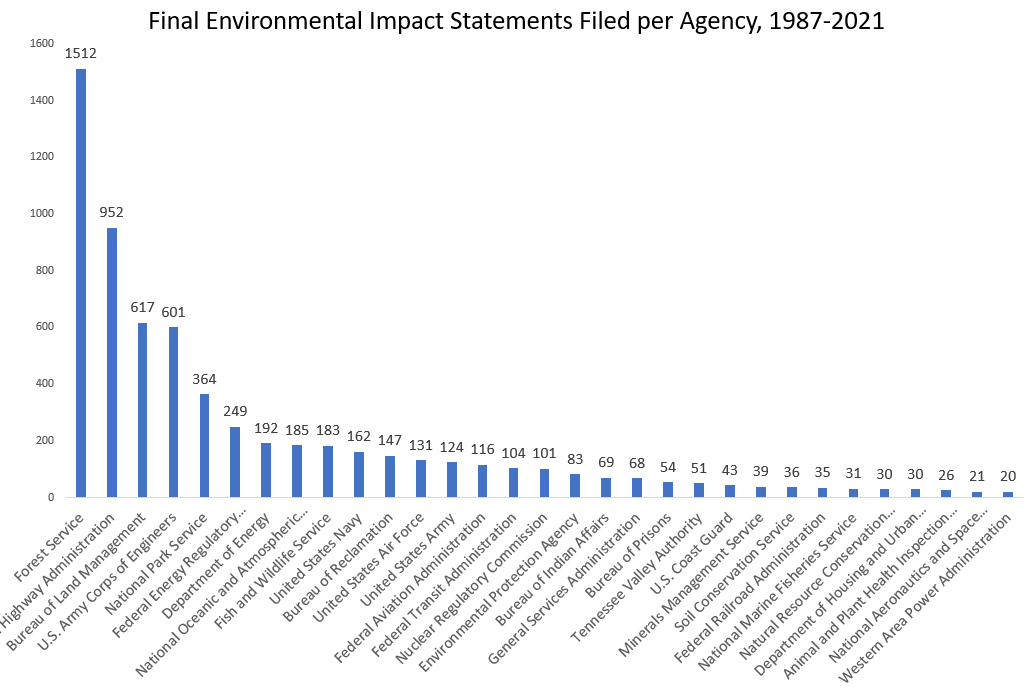

Different agencies, for instance, differ greatly in the number of NEPA analyses they perform. Over the past 35 years, nearly 100 federal agencies have had to produce an environmental impact statement, but just 10 agencies are responsible for 75% of EISs.

Agencies charged with management of federal lands (such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management), and responsible for building large scale infrastructure (such as the Federal Highway Administration and the Army Corps of Engineers) are responsible for an overwhelmingly large portion of NEPA efforts - those 4 agencies are responsible for more than 50% of environmental impact statements produced over the last 35 years.

The same seems to be true for EAs (though the data here isn’t great.) In 2015 (the last year we have data), just 2 agencies (the Bureau of Land management and the Corps of Engineers) were responsible for more than 50% of environmental assessments.

(Note that some of the agencies that produce the most EAs aren’t the ones that produce the most EISs - HUD and the Department of Rural Development notably seem to produce a lot of EAs but relatively few EISs.)

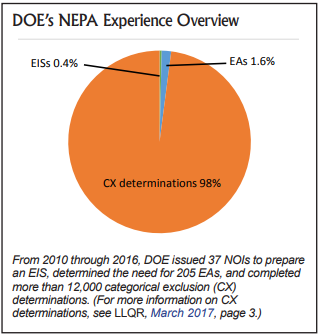

Agencies also vary in the proportion of actions that require a higher tier of NEPA analysis. For the Department of Energy, for instance, 98% of their actions are categorical exclusions, 1.6% require an EA, and just 0.4% require an EIS [1].

For the Forest Service, on the other hand, 15.9% and 1.9% of agency actions require an EA or an EIS, respectively (~10x and ~4x the DoE rate.)

Inter-agency variation also shows up in the amount of effort required to produce a given analysis. The length of environmental impact statements, for instance, varies greatly from agency to agency:

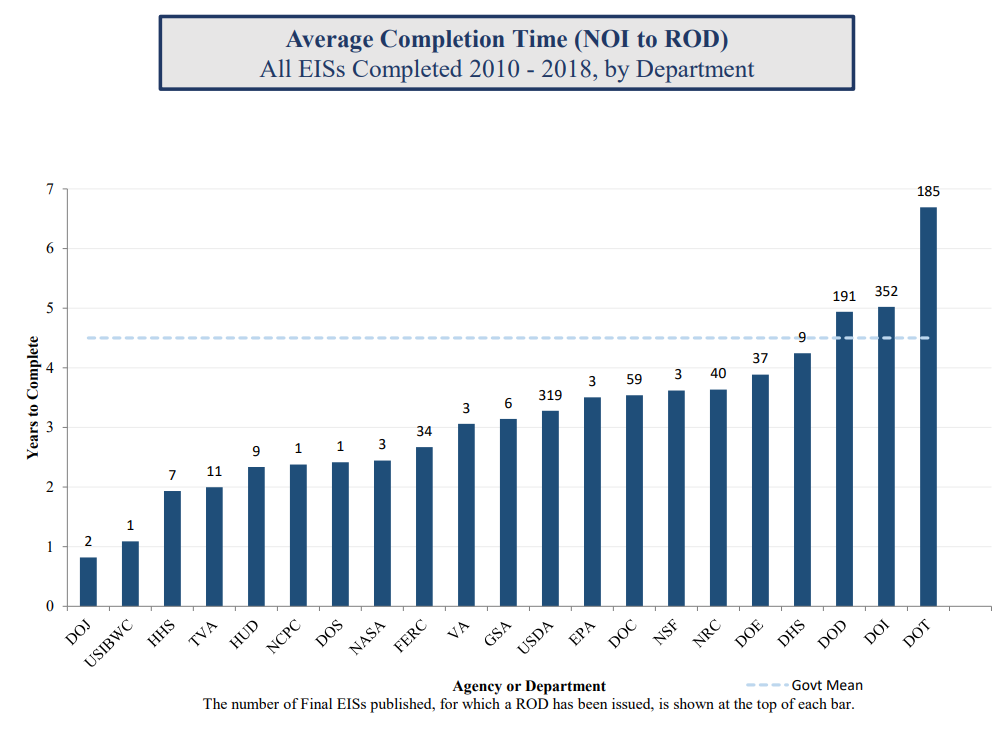

As does the time to complete them:

The same is true if we look at lower tiers of analysis. For environmental assessments, some agencies seem to routinely produce very short ones. Every EA I found for the Corps of Engineers, for instance, was less than 100 pages, with many fewer than 30 pages (this USDA report suggests the Corps of Engineers has a very different NEPA process and culture than other agencies.) The FAA, on the other hand, seems to produce enormous EAs. Their EA for a new runway approach procedure at Boston Logan is over 2100 pages including appendices, and their EA for licensing SpaceX’s Boca Chica facility is over 1200 pages.

Likewise, the amount of work a categorical exclusion requires seems to vary greatly between agencies. For some, such as the Department of Energy, it’s mostly just filling out the proper form, and takes just 1 or 2 days to complete. In other cases, the categorical exclusion is a more substantial undertaking. The median time to complete a Forest Service categorical exclusion, for instance, was 105 days as of 2018. And for the Federal Highway Administration, Trnka 2014 notes that “The template documents for preparing FHWA CEs in some states are 20 or more pages long and routinely lead to documents of 100 or more pages.” This discussion of the Florida I-10 bridge replacement notes that it took several months to approve the CE, as it had to be signed off by an extremely backlogged Coast Guard.

Here’s the FHWA describing the procedure that might be required to determine if a road falls under a categorical exclusion:

Now let's look at a second project where the widening of the road requires additional right-of-way from a public park. To decrease crashes on an existing roadway, shoulders will be added. In a site visit with the State DOT, it was determined that the CE [categorical exclusion] is likely appropriate under the D-list in the regulation. But because of the need for right-of-way and potential impacts to public land, the local public agency (LPA) is asked to:

• Conduct several studies related to the presence of endangered species and archeological sites

• Coordinate with FHWA to address resources and potential use of the public park

• Follow the State DOT's public involvement procedures for formal public input

The studies confirmed that there were no significant environmental impacts.

Variation between agencies also exists for NEPA analysis preparation times. Dewitt 2013 noted that between 2006 and 2010, though across all agencies average EIS preparation time went up, several agencies (such as the Corps of Engineers, Forest Service, and Highway Administration) had their preparation times fall. And looking at the DoE, their average EIS preparation time was fairly constant from the mid 1990s up until ~2011:

There can also be significant variation in NEPA operations within a single agency over time. The Department of Energy, for instance, was for many years an organization that treated NEPA compliance as an afterthought. But in 1989, a new Secretary of Energy (James Watkins) emphasized compliance with environmental laws (including NEPA), and substantially changed the organization’s NEPA procedures, and increased the number of EISs they performed:

Variation might also exist within a single agency between offices. Fleischman 2020 noted that “there appears to be substantial heterogeneity within the USFS concerning how NEPA processes are handled, in terms of both level of analysis (i.e., some offices perform many EISs, others many EAs or CEs) and time spent on analysis.”

NEPA trends

Let’s look a little closer at the data around NEPA analyses.

For EISs, as we’ve seen, these are long documents. As of 2018 the average page length of an EIS was 661 pages (including appendices.) And they take a long time to complete - as of 2018 the average time between the “Notice of Intent (NOI)” (when an agency files it’s intent to create an EIS) and the “Record of Decision (ROD)” (when it makes its official decision for how to proceed) is 4.5 years (and this likely understates the true preparation time, as work often begins before the NOI is filed.)

These seem to be increasing over time - the documented preparation time for EISs rose nearly 50% between 2000 and 2018:

For page length trends, I couldn’t find any overall summaries, but the DoE noted in 2017 that “the average length of DoE EISs have more than doubled over the past 20 years.”

The actual number of NEPA analyses, though, seem to be decreasing. Here’s final EISs filed per year over time:

(As far as I can tell, this does not include EISs completed under ARRA.)

Less data is available, but it appears something similar is true for EAS, with fewer and fewer of them being produced per year (though most of these datapoints are estimates and likely have wide error bars):

For CEs there’s even less data, but there’s some suggestive evidence. Fleischman 2020 noted that for the Forest Service the number of categorical exclusions is dropping over time:

It’s not clear what the mechanism is here. Over time, we should naturally expect fewer EAs and more CEs (once a type of project is understood to have few or no significant effects, future projects similar to it can often be a CE.) But this wouldn’t explain a drop across all levels.

One possible explanation is a reduction in federal resources devoted to NEPA/environmental compliance. A 2003 study noted that NEPA staff and budgets across all agencies had been repeatedly reduced, and staff were being asked to “do more with less”, and Fleischman 2020 noted that “flat or declining annual appropriations and dramatically rising fire suppression costs” were likely part of the reason for fewer Forest Service NEPA analyses.

NEPA costs

How much do these NEPA analyses cost?

Getting a clear answer to this is difficult, partially because there’s often no clear distinction as to what constitutes a “NEPA task”, partially because agencies in general don’t attempt to track this information, and partially because (once again) there’s significant variation from agency to agency. In general, costs track the time and effort required to perform the analysis, with CEs being cheaper than EAs, and EAs being cheaper than EISs.

In 2003 the CEQ estimated that “small” EAs cost between $5000 and $20,000, “large” EAs cost between $50,000 and $200,000, and EISs typically cost between $250,000 and $2,000,000.

A Forest Service official testified in 2007 that their CEs cost approximately $50,000 on average, EAs $200,000 on average, and EISs $1,000,000 on average.

The DOE (which tracked its NEPA contractor costs until 2017) noted that in 2016 their average EA cost was $386,000, and their average EIS cost was $7.5 million (CE costs were described as “not significant”.) EIS cost was relatively steady over time, while EA cost had seen a large recent trend upward

Most reports note that the cost for a NEPA analysis is typically a small fraction of the overall project cost (typically less than 1%.)

Like with all things NEPA, these costs seem to be heavily right-skewed, with a small number of EAs/EISs dramatically more expensive than others. The years where the DOEs average EIS cost spiked, for instance, were years when a particularly expensive EIS (such as the one for Yucca Mountain) was completed. In general, NEPA analyses seem to form a series of overlapping right-skewed distributions, with the longest and most arduous CEs more effort than the easiest EAs, and the largest EAs more work than the simplest EISs.

Even though most federal government actions fall under a categorical exclusion, the largest and most complex projects will invariably need a higher level of NEPA analysis, so in per-dollar terms the fraction of EAs and EISs is much higher. The Highway Administration, for instance, noted in 2001 that while 91% of projects could be classified as a categorical exclusion, this represented only 74% of project dollars.

NEPA, the courts, and uncertainty

The mechanism by which NEPA compliance is enforced is via the courts - agencies can be sued under the Administrative Procedures Act for not properly complying with NEPA (using an inappropriate tier of analysis for an action, ignoring certain likely impacts, etc.) NEPA lawsuits are common - the Department of Justice has noted that NEPA is the most litigated environmental law, and that 1 out of every 450 federal actions taken to comply with NEPA are challenged in court.

In practice, this creates something of a moving target for NEPA compliance. Agencies must be constantly monitoring court outcomes to determine what compliance requires (this is sometimes described as “NEPA common law”), and over time more and more potential impacts have had to be included in NEPA analyses. The National Association of Environmental Professionals helpfully publishes a relevant list of NEPA case outcomes in its annual report.

The frequency of NEPA litigation is partly due to the fact that, while NEPA lawsuits often target legitimate inadequacies (such as not considering the risks of an infectious pathogen research facility being built near a major population center), they are sometimes used as a weapon by activist groups to try to stop projects they don’t like. While lawsuits can’t stop a project permanently, the hope is that a lawsuit will result in an injunction that stops the project temporarily, and that the delay will make the project unattractive enough to cancel:

An environmental activist opposing a missile defense project stated that “the hope is that delay [occasioned by NEPA litigation] will lead to cancellation...That’s what we always hope for in these suits.”

The executive director of the Surface Transportation Policy Project testified that “In the struggle between proponents and opponents of a…project, the best an opponent can hope for is to delay things until the proponents change their minds or tire of the fight.”

A “grassroots litigation training manual” produced by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund stated “in an area devoid of endangered species, impacts to waterways and floodplains or of federal funding, NEPA may be the only tool that grassroots groups have [to fight highway projects]”.

And Forest Service officials noted that many groups would simply oppose or litigate any project at all (often because this helped them raise more funding.)

While most NEPA analyses don’t get litigated (as of 2013 there were about 100 NEPA lawsuits filed per year), in practice the threat of a lawsuit seems to push agencies towards producing “litigation-proof” NEPA documents:

Mortimer 2011, for instance, found that NEPA leaders decide on the level of analysis to do primarily based on perceptions of public controversy and litigation risk.

One agency testified in 2005 to the House Committee on NEPA reform that “that litigation – or the threat of litigation – has in effect “forced” them to spend as much as necessary to create “bullet proof” documents.”

A report by the Forest Service notes that “Team members often believe that much of their work is ‘for the courts’ and not particularly useful for line officers who make decisions.”

Testimony from a mining executive in 2005 noted that “there are now very few issues an agency is willing to consider insignificant, due to concern about having their decision appealed”, concerns which have been echoed by other industry stakeholders.

And Stern 2014 notes that:

Despite calls for shorter NEPA documents in the Forest Service, most IDTLs and team members felt pressure to include what they considered to be otherwise unnecessary information in their NEPA documents. Interviewees described pressure from the DM in some cases to do so. In other cases, this was attributed directly to a general fear of the public pointing out that something was missed and reopening the NEPA process.

An example of this is the threat of lawsuits incentivizing the inclusion of more and more research in environmental analyses, regardless of its merits:

An excellent illustration of excessive analysis due to management uncertainty is the Beschta Report. Commissioned by the Pacific Rivers Council in 1995, eight scientists drafted a paper, “Wildfire and Salvage Logging,” commonly known as the Beschta Report.

The paper has never been published in any scientific or professional journal, nor has it ever been subject to any formal peer review. In 1995, Forest Service scientists and managers expressed strong reservations about the report, which contains many unsubstantiated statements and assumptions. Nevertheless, the courts have sometimes shown support.

Groups have challenged postfire recovery projects on the grounds that the Forest Service has failed to consider the Beschta Report. In four cases, the courts have ruled that Forest Service decisions violated NEPA because the associated records did not adequately document the agency’s consideration of the Beschta Report. In two other cases, courts have ruled in favor of the Forest Service on this issue.

In view of the court record, forest planners might feel compelled to thoroughly document their consideration of the Beschta Report’s principles and recommendations, even though the underlying land management issues are already addressed in the record. That includes documenting why some elements of the Beschta Report are not relevant to the specific proposed project.

The court record has inspired some groups to demand that the Forest Service consider other papers and articles supposedly relevant to proposed actions. Sometimes the proffered list of references exceeds 100 entries. To minimize the risk of adverse judicial opinions, land managers might feel constrained to fully document within the body of the NEPA document their detailed consideration of each and every paper or article.

This mechanism seems to be behind the length of NEPA documents. The 1978 CEQ regulations state that an EA should generally be less than 75 pages, and an EIS should generally be less than 150 pages. But the uncertainty of what’s needed to comply with NEPA, and the natural risk aversion of government agencies, pushes these documents to be longer and longer.

In practice, figuring out what “bulletproof” entails is difficult. Stern 2014 gives an example of the Forest Service trying to figure out what sort of watershed analysis model is most likely to hold up in court:

…In one case, for example, an IDTL asked the Regional Office whether they could use a particular watershed model that had been used elsewhere. Personnel in the Regional Office instructed the team not to use the model because it would represent a departure from the traditional approach used on the specific forest and could expose the process to additional external scrutiny by setting a new precedent. The IDTL described the response from the Regional Office after the ID team submitted their preliminary report, which did not include the model.

“It was like [from the Region], ‘Hey, you need to run some models because there was this court decision, and it was up-held because they had model information, so you got to run the model for this.’ [laughing] It was kind of like, ‘okay that’s a 180 from what you told us initially.’ And then after the model was run, and we sent the document out, [the Region came back and said], ‘Oh jeez, maybe you shouldn’t have run the model because… the court case was reversed.’ [laughing]”

The uncertainty that the NEPA process creates - how thorough of an analysis will be required, how long it will take to perform, what sorts of mitigations will be required, what sorts of follow-up analysis will be required, will the analysis get litigated - makes it difficult to plan projects with substantial NEPA requirements. A mining executive noted that the NEPA process has resulted in the US having unusually burdensome permitting requirements by world standards:

In considering a new project the first thing I am asked is how long will it take and what will it cost to get it permitted. I can answer this question with a high degree of confidence in most jurisdictions around the world, with the exception of the United States. When I first began working with NEPA in the mid 1980s the time and cost to prepare an EIS for a mining project took about 18 months and cost about $250,000-$300,000. Today [2005] an EIS for a mining project may take 5-8 years and cost $7-8 million or more, before factoring in expected appeals and litigation of the ultimate decision. Thus, it is very difficult to make business decisions in the US under the current permitting environment on federal lands.

Reitze 2012 notes that NEPA is used to increase the costs and unpredictability of fossil fuel development, in an attempt to make renewable energy more attractive by comparison. And Glen 2022 notes that uncertainty around NEPA litigation also makes planning renewable energy projects (in this case, wind power) more difficult and risky. A transmission line executive noted in 2009 that the uncertainty and unclear case law around considering climate change impacts had created a “nightmare” for him.

This uncertainty also makes changing NEPA somewhat risky. Experts have noted, for instance, that rules to accelerate NEPA processes or impose maximum timelines might result in more of them being challenged in court (by failing to take the proper “hard look”). One consultant for energy projects suggested that the Trump-era NEPA changes (which have since been rolled back) were likely to increase project uncertainty and delay of energy projects in the short term, as the changes would result in increased litigation.

Untangling the effects of NEPA

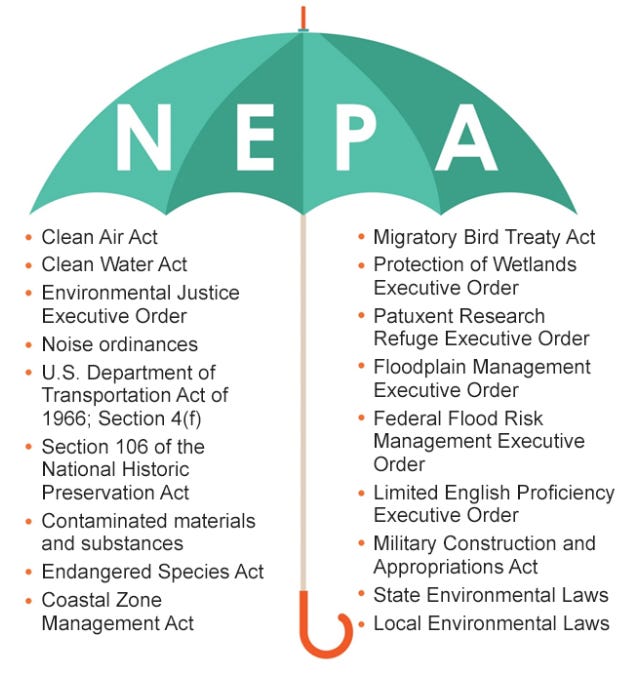

One challenge with understanding the effects of NEPA is that it’s typically just one of many environmental laws a project must comply with. This discussion of a North Carolina light rail project’s NEPA process, for instance, lists 13 other federal environmental laws and executive orders the project had to comply with, and this page lists 20 other federal regulations other than NEPA that govern Forest Service actions. NEPA is often referred to as an “umbrella statute” - an overarching process that organizations can use to manage the entire environmental compliance process.

This makes it unclear what delays are caused by NEPA, and what are actually caused by something else under the “NEPA umbrella.” For highway projects, Luther 2012 notes that “this use of NEPA as an “umbrella” compliance process can blur the distinction between what is required under NEPA and what is required under separate authority” and that “despite the focus on the NEPA process, it is unclear whether or how changes to that process would result in faster highway project delivery.” A 2014 report from the GAO came to similar conclusions, noting that the time for completing CEs and EAs often depended on how many environmental regulations and processes the project needed to comply with.

NEPA also tends to mask (and get blamed for) other sources of delay that occur during the NEPA process. If an organization de-prioritizes a project, or has insufficient funding for it, or runs into local opposition, that might show up as an extended time to complete the NEPA analysis, despite the fact that the delay was due to other factors.

One illustration of this is how quickly NEPA analyses often get done in urgent situations where everyone is aligned, and common sources of delay aren’t present. One example of this is distributing stimulus funds following the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009. Over 190,000 projects, totalling $300 billion dollars worth of stimulus funds, were required to have NEPA reviews before the projects could begin. After the passage of ARRA, categorical exclusions were completed at the rate of more than 400 per day, and 670 environmental impact statements were completed over the next 7 months.

Another example is following a bridge collapse, where state DoTs work quickly to restore the bridge as quickly as possible Following the I35 bridge collapse in Minneapolis, for instance, the environmental review for the replacement bridge was completed in less than 2 months. A report by the FHWA notes that following a bridge collapse, many of the frequent causes of highway project delay are absent:

NEPA and foregone benefits

Besides the direct costs of compliance, another potential cost of the NEPA process is the projects that don’t occur at all. The NEPA process is effectively a tax on any major government action, and like any tax, we’d expect it to result in less of what it taxes. Is there any evidence this occurs?

Several industry executives have stated that in some cases they choose not to do projects rather than navigate the NEPA process. The previously quoted mining executive, for instance, testified that “for most projects, the time, cost, and uncertainty of obtaining approvals is simply too great in the United States, and mining investment looks elsewhere. The cumbersome NEPA process is key to this consideration.” And an executive from Vulcan Materials noted that “in some cases we conclude that the process is so burdensome we choose to not pursue aggregate resources rather than work through the drawn out and costly NEPA process.”

This also seems to occur within government agencies. Stern 2014 found that Forest Service planners alter their plans to make them less ambitious as a way to avoid NEPA lawsuits.

Some evidence is indirect. For instance, a GAO study found that 33 states had avoided taking federal money for highway projects specifically so they could avoid the NEPA process. And Culhane 1990 suggests that NEPA compliance was partly to blame behind the decrease in new Corps of Engineers projects:

Seven short years of EIS commenting and public participation reduced the Corps from its position as the premier powerful agency in the federal bureaucracy to the debacle of President Carter's "hit list."8 " After the "hit list" affair, the Corps endured a severe drought, and authorized no new water projects until 1984.

Because the NEPA process adds a large review time to the beginning of a project, this sometimes screens off projects that by their nature need to be completed quickly. A Forest Service report noted that a drawn out environmental analysis and litigation process slowed a prescribed burn project meant to reduce the risk of wildfire, and the wildfire eventually occurred:

In December 1995, a severe winter storm left nearly 35,000 acres of windthrown trees on the Six Rivers National Forest in California. The storm’s effects created catastrophic wildland fire conditions, with the fuel loading reaching an estimated 300 to 400 tons per acre—ten times the manageable level of 30 to 40 tons per acre.

The forest’s management team proposed a salvage and restoration project to remove excessive fuels and conduct a series of prescribed burns to mitigate the threat to the watershed. From 1996 through the summer of 1999, the forest wrestled its way through analytical and procedural requirements, managing to treat only 1,600 acres.

By September 1999, nature would no longer wait. The Megram and Fawn Fires consumed the untreated area, plus another 90,000 acres. Afterward, the forest was required to perform a new analysis of the watershed, because postfire conditions were now very different. A new round of processes began, repeating the steps taken from 1996 to 1999.

Seven years after the original blowdown, the Megram project was appealed, litigated, and ultimately enjoined by a federal district court. The plan to address the effects of the firestorm—a direct result of the windstorm—remains in limbo.

Because it adds cost and uncertainty to any new major project, NEPA is effectively a bias towards the status quo. As one environmental lawyer noted, “NEPA, being procedural and not substantive, is a hefty sword. It stops the projects many groups do like, along with the ones they don’t like.”

Like with any process that solicits public input, NEPA also seems easily captured by small groups with strongly held opinions, and thus subject to standard NIMBY effects. In some cases, it seems like NEPA makes projects unusually susceptible to a minority of strong opinions - for instance, agencies have noted that NEPA project challenges often originate from opponents “who are based out of state and not part of the communities they purport to represent.”

NEPA benefits and project management

It’s easy to find criticism of the NEPA process, but what are the benefits of it?

A report from the USDA notes that “the literature points to only a few effects of NEPA upon agencies’ planning processes that are not widely debated”, which are:

Agency staff becoming less homogenous (staff have a wider range of training and backgrounds)

Increased transparency of agency analysis and decision making

A wider range of alternatives for projects is typically considered.

But the report notes that “these shifts have come with associated costs of long delays in decision making as analyses are performed and reports are produced, and of high-priced responses to litigation of the agency processes.”

Some agency officials have also admitted that following the NEPA process resulted in considering alternatives that they wouldn’t have otherwise looked at:

One of our alternatives… I really don’t believe it would have been there but for the public involvement. We had a lot of people say…we just don’t want you to do any timber harvests. We just want you to thin the stuff and leave it. Nothing commercial. And you know, most of us just rolled our eyes and said, “Oh, that’s ridiculous, we can’t possibly do that.” And so, we said “OK, we’ll go through the process honestly and put up with this dumb idea.” Turned out the alternative was very feasible and was really quite reasonable and quite reasonably effective. It wasn’t as effective as some of the other alternatives, but you know, at the start we would have just completely discarded it except that we had a lot of people clamoring for it.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental advocacy group and major NEPA champion (they’re part of the ProtectNEPA.org coalition, for instance), describes the benefits of the NEPA process:

At the heart of this review process is the agencies' obligation to consider alternatives to their original project designs, which motivates them to think outside the box, resulting in better projects that save money and reduce negative impacts. It also gives members of the public a voice in project design by letting them suggest alternatives, which promotes collaboration in planning and buy-in on final decisions.

And they list a few examples of successful NEPA processes:

“In California, the NEPA review process exposed the devastating impacts of the Army Corps of Engineers' plan to dredge the Bolinas Lagoon, one of the most pristine tidal lagoons in the state. While the proposal aimed to prevent silting in the lagoon, environmental reviews actually found that it would increase siltation. As a result, this misguided plan was abandoned in 2001, saving taxpayers $133 million. “

“The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) proposed to construct the Palestine Commons Senior Living Facility project -- 69-units of elderly housing in a three-story structure in Kansas City, Missouri. HUD planned to build the facility on an old petroleum-tank site to contribute to Kansas City's redevelopment plan and support community revitalization. However, the NEPA process revealed potential soil and groundwater contamination on the site. Thanks to this law, the project plan was modified to include site remediation and thereby protect the facility's future residents.”

“The Route 52 causeway between Ocean City and Somers Point, first built in the 1930's, faced restricted lane and speed usage as it fell into disrepair, and the lack of shoulders posed a safety hazard to motorists. New Jersey and the Federal Highway Administration sought to rebuild the route to better serve the area. Thanks to input from area residents and other federal agencies during the NEPA process, the final environmental impact statement identified an alternative that minimized the route's environmental and socioeconomic impacts. For example, the final project avoided potentially extensive dredging and damage to wetlands as well as extensive property takings and changes in land usage. New bike paths, walking trails, and boat ramps are part of the causeway and mitigation measures were taken to account for the limited dredging and wetlands loss. Construction was finished in 2012.”

(Many more available at the link)

NEPA is often described by proponents as “a tool to make decisions” - the CEQ regulations, for instance, state that “The NEPA process is intended to help public officials make decisions that are based on understanding of environmental consequences” and that “NEPAs purpose…is to foster excellent action.” But it’s unclear how successful it is at this. In a survey of 25 NEPA officials, only 4 described the quality of decision as mattering for whether the NEPA process was successful or not, and that “staff interviewed in this study tended to focus more upon the processes through which they could complete the procedural requirements of the act with least resistance.” A 1986 study of environmental impact statements found that only 30% accurately predicted a project's impacts, with most too vague or abstract to evaluate. It also seems telling that no organizations I’m aware of willingly adopt the NEPA process.

Reading through examples of successful NEPA processes, it seems as if the purpose of the NEPA process as it exists is to try and legislate good project management - ensure that requirements are gathered upfront, the relevant laws are considered, many possible solutions are proposed, relevant stakeholders are brought on board and have their views considered, etc. - and that many examples of NEPA “successes” (such as “ensuring compliance with all relevant laws”) are things that a competent project manager would have done anyway.

Overall, it seems like NEPA has some level of success at improving average project outcomes (probably by screening off certain types of extremely poor planning), but if you think the government needs to be better at project management there are probably better ways of doing that. And of course, any success would have to be balanced against the large costs that the NEPA process incurs.

NEPA as an anti-law

The more you look at NEPA, the more it seems like a very strange law.

Arguably, the purpose of a law is two-fold:

To prevent or encourage some particular thing that society thinks is good/bad. Laws against drunk driving exist, for instance, because drunk driving is harmful and as a society we want less of it.

To solve coordination problems and create predictability. Laws that enforce driving on one side of the road and not the other, for instance, exist not because one side is better than the other but because it’s useful if everyone agrees, and everyone knows what to expect from other drivers.

NEPA arguably does neither of these things.

For the first, as we’ve seen NEPA does not require environmental impacts be limited, only thoroughly documented through a specific process. (To the extent that NEPA does result in reduced environmental impacts, it seems like an indirect effect of making doing anything procedurally costly.) And the thing that NEPA does create directly - additional government process - is something we want less of.

For the second, NEPA doesn’t create predictability. In fact, it greatly reduces predictability and increases coordination cost and risk, because it’s so unclear what’s needed to meet NEPA requirements. Agencies are forced into risk-reduction strategies that at best require spending significant time and resources to defend against possible litigation, and at worst mean projects don’t happen at all.

[0] - This is in contrast to CEQA, which does require that environmental impacts be mitigated.

[1] - The Department of Energy isn’t necessarily the most representative agency with respect to NEPA implementation, but much more data is available for it - between 1994 and 2017 the DoE issued a quarterly “NEPA best practices” newsletter that included, among other things, costs and completion times for EISs and EAs.

It's worth emphasizing, as you do for roughly the last third of the article, that NEPA's main issue is that the chosen enforcement mechanism is "adversarial legal process". This is just an extension of the rampant rent-seeking/regulatory capture by the wonderful legal practitioner community in the United States. Hell, the ADA is enforced the same way!

If we find the NEPA framework valuable (I'm agnostic trending towards "burn it to the ground" after having watched it take 4 years to do an environmental impact review to place a goddamned box culvert on the site of an existing partially collapsed culvert), most of its worst excesses could be curtailed by making the actual EPA responsible for project determinations and enforcement.

Then, if the so-called "public" comes up with an objection, they can go take it up with the EPA while the project moves forward.

So, one thing not mentioned here, which may address some of the questions about declining numbers of coverage is the existence (and I believe expansion in use) of programmatic NEPA efforts. So, a classical one is pesticide application. Instead of doing compliance work on individual efforts, you lump all your future intended pesticide actions together and either do a programmatic CX or a programmatic EA.

More expensive up front, but it usually balances out over time. The main problem with this, beyond up-front cost, is that it usually reduces flexibility. Under the old system, if a new pesticide came out and you wanted to use it on the next project, that didn't really change anything. But now, if you want to, you either need to amend your programmatic coverage (which is generally more expensive than an individual CX, as there's a far wider array of actions/effects/area to cover) or do an individual CX.

Now, the individual CX isn't actually any more expensive than it would have been under the old system (barring inflation/COLA and other cost increases which would have happened either way), but the comparison in your tightened budget is now:

1) Just use the old programmatic and pay basically nothing for compliance.

2) Do a new individual CX and pay that cost.

And so there's a tendency to get stuck in the old way of doing things. This is a narrower example of the status quo bias you mention throughout the piece.