Lessons from Shipbuilding Productivity, Part II

Continued from Part I

When WWII ended, the world, and especially the US, was suddenly faced with far more ships and shipbuilding capacity than it needed. Merchant ship capacity had actually increased by 20% between 1939 and 1947, much of which was due to the enormous number of ships built by the US during the war. The US had increased its merchant ship volume by 286% during the same years, going from having 13% of the world merchant fleet to 36%. Of the 2700(!) Liberty Ships built during the war, 2400 of them survived [0].

As quickly as it had been created, the US's shipbuilding machine was dismantled. The Kaiser and Bechtel yards closed [1], and Kaiser left the shipbuilding business. The former superintendent of Kaiser's Swan Island facility, Elmer Hann, ended up at National Bulk Carriers (NBC), a company owned by shipping magnate Daniel Ludwig that built oil tankers and bulk transport ships. Ludwig was interested in building increasingly larger ships and tankers but was limited by the size of the facilities at their Norfolk Virginia shipyards. Ludwig tasked Hann with finding larger facilities [2].

Hann eventually decided on the Kure shipyards in Japan, which had been responsible for building the enormous Yamato-class battleships and had survived the war largely intact [3]. Among the conditions required to secure the lease were that Japanese engineers be allowed to visit the facilities and learn the shipbuilding techniques being used (ultimately over 4000 engineers would visit the yard.)

Hann brought with him the techniques used in Liberty Ship construction - using welded construction, assembling the ship from large, prefabricated assemblies or blocks (which in turn were made from smaller subassemblies), structuring the process to allow as much work as possible to be performed before point of final assembly, and arranging the yard to allow for the smooth flow of material between stations.

These methods would then be modified and improved. One source of improvement was Hisashi Shinto, NBC's chief engineer at Kure. Shinto had been a planning engineer for Japan's shipbuilding operations early on in the war and had later been transferred to work on aircraft production. While there, Shinto was struck by the detailed plans and drawings used for airplane fabrication, which provided assembly instructions and material needed for each step of fabrication. He wondered whether such a system might be useful for shipbuilding, and was given the chance to try it at NBC [4].

Another influence was the concepts of statistical process control, and how to find and remove known causes of variation, which had been developed in the 1920s and 30s by Walter Shewhart and popularized by W. Edwards Deming. Deming's work would become incredibly popular in postwar Japan - he would give 35 lectures to Japanese managers and engineers in 1950 alone, and over the next 30 years would visit Japan 19 times. Deming's and Shewhart's methods would profoundly influence many Japanese industries, including automobile manufacturing as well as shipbuilding [5].

These ideas resulted in a new method of building ships that was dramatically more productive than previous methods. Visits from other engineers meant that the techniques quickly spread to other shipbuilders, and Japan went from 7% of world ship production by tonnage in 1950, to nearly 50% by 1970, a marketshare it managed to hold well into the late 2000s despite the entrance of low-cost competitors like Korea.

Much like the reversal with Japanese car manufacturing (where Japan adopted and modified US methods, improving them so much that the US was eventually copying them), by the 70s and 80s there were efforts in the US to try to understand the Japanese shipbuilding methods. Japanese shipyards could produce ships far cheaper than US yards - in the early 1980s, it was estimated that Japan could produce ships using just 25-35% of the labor, and 65-75% of the material cost, as US yards. They could also build ships faster - US shipyards reliably delivered ships months or years late, while Japanese shipyards were able to deliver their ships on time or even early. Japanese ships could be built in less than half the time as US ships.

Much of this work was sponsored by the government under the National Shipbuilding Research Program. Much of this work was published in the 80s and 90s, but it’s my impression that shipbuilding still uses similar methods to these.

How the system worked

So how does this shipbuilding system work?

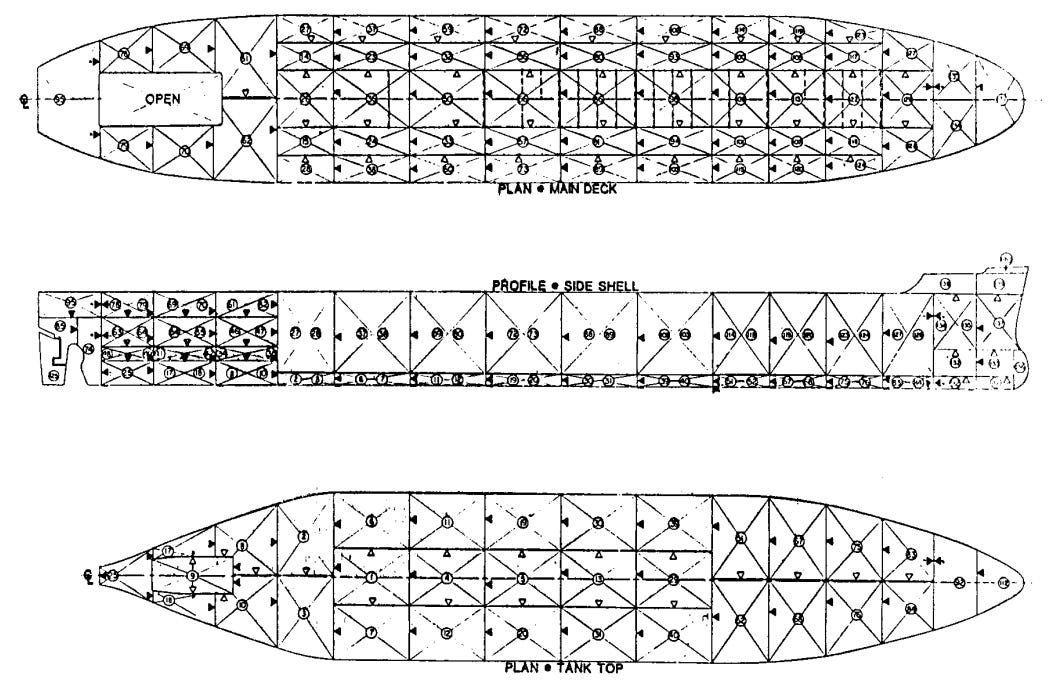

It starts with how the work is organized. Much like a building, initial design is based on separate but interacting functional systems - designs and drawings will be produced for the electrical system, the ventilation system, the engine machinery, etc. This information is then reorganized for construction and assembly - a ship will be divided into individual blocks or zones, separate geographic areas ship that will be built separately then stitched together. Large blocks are broken down into smaller assemblies, which in turn will be broken down into even smaller ones, until arriving at a manageable unit of work. A given subassembly might have many different functional systems on it (a portion of the hull, electrical wiring, ventilation ducts, piping, etc.), and the block/subassembly becomes the unit of organization for construction rather than functional system. The process of combining small subassemblies to large blocks and then an entire ship is carefully sequenced, with each step in the process called a 'stage'. Each stage of construction will be performed with composite drawings showing all the assembly steps and materials that particular subassembly requires.

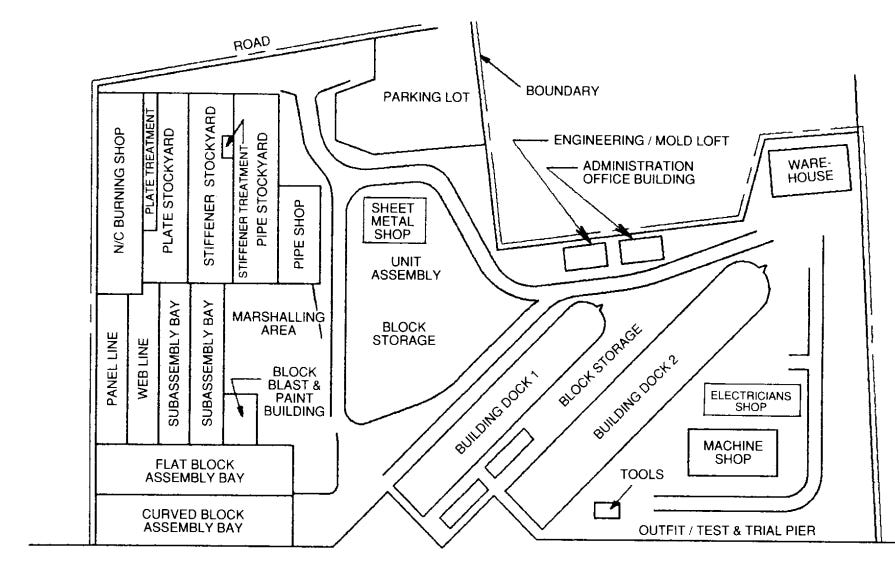

Each stage of the process will be assigned to a particular area of the shipyard (called a process lane) devoted to building certain types of assemblies. One of the key concepts behind this method of shipbuilding is something called "Group Technology", the idea being that even if you're not engaged in pure repetition (manufacturing large numbers of identical ships made from identical parts), building a ship still means performing similar sorts of tasks over and over again. These tasks will use similar sorts of equipment, have similar assembly steps, and require the solving of similar sorts of problems. By grouping similar types of tasks together and having assembly stations which focus on just those tasks, you can get some of the benefits of a uniform production process (such as reduced setup time) while producing a series of unique products.

For instance, a ship will have a huge number of components made from steel plate, with different components requiring different sorts of plate forming work. A shipyard thus might have one process lane for simple flat plate assemblies, others for assemblies that require curved plates, others for assemblies that have complex geometries. For curved steel plate, there may in turn be separate process lanes for subassemblies which must be shaped using presses vs subassemblies which require line heating.

Manufacturing and Lean folks will recognize this as basically a version of cellular manufacturing, where machines are grouped into cells for creating parts with similar characteristics and arranged to minimize travel distance and worker movement. Interestingly, early descriptions of these shipbuilding processes from the 70s and 80s don't make any mention of Lean (obviously), but by the 90s it starts to work its way into some of the descriptions.

Beyond just the hull assembly, outfitting (installing other ship systems) proceeds by block/zone as well. It was found that the farther upstream in the production process outfitting work is performed, the easier and less expensive it is. Outfitting work at an assembly station allows the use of equipment that might be otherwise be too heavy or time-consuming to move, allows for 360-degree unrestricted access, and eliminates the need for workers to work overhead - assemblies are designed to be rotated by crane so workers can always work at the optimal orientation. And because systems installation can proceed before the hull is complete, the critical path is shortened dramatically, allowing the ship to be built much faster.

Statistical control

Stitching together many separate steel components into a watertight object requires tightly controlling manufacturing accuracy. Inaccurate parts mean gaps or overlaps when joining them together, and even small errors can stack up and prevent proper alignment, causing costly and time-consuming rework to get everything to fit together properly. Preventing this means producing parts and assemblies within a certain range of tolerance and making sure they stay there.

Accuracy control thus becomes a key component of this method of shipbuilding. Shipbuilders go to great lengths to understand the variations in the production process (such as the different types of distortion induced by welding, pressing, and line heating), and trying to reduce it. For instance, a great deal of effort was expended in developing line heating techniques, which allowed for the more accurate shaping of curved parts, and could also reduce the distortions induced by welding [6]. As much as anything else, it's this careful work of defining an allowable variation in parts, and carefully monitoring whether it's been exceeded or not, that allows these assembly methods to work efficiently.

All this effort requires a great deal of administrative and engineering overhead compared to more traditional methods. Highly accurate and detailed fabrication drawings needed to be created for every step of the process, showing material requirements, process steps, and assembly instructions. Work must be carefully broken down in a way that balances material flow between process lanes (to avoid bottlenecks), and that accurately groups similar tasks together (to ensure the work goes to the proper assembly area, and that the statistical tolerances for a given component are valid.) Blocks must be designed so that assembly is as simple as possible - by sizing blocks so their edges don't interfere with components, for instance, or by arranging pipes so they can share mounting brackets. The process must be monitored, and deviations must be hunted down and corrected. Without all this additional technical effort, significant rework must be performed, material flow grinds to a halt, and productivity plummets.

Shipbuilding vs the Toyota Production System

Taking a step back, the entire in some ways process resembles a scaled-up version of the Toyota Production System (unsurprising, since it was developed at the same time, in the same country, and has many of the same influences, ie: Deming.) Emphasis is placed on quality and reduction of variance, which minimizes rework and thus costs. Like the Toyota Production System, this method of production requires high quality to function properly (with low quality, parts don’t fit together properly at assembly, causing delays while parts get reworked.) The process structure of lots of small, well-defined assembly steps with carefully tracked quality metrics at each step allows for a process of continuous improvement. Emphasis is placed on small units of work rather than large work packages to minimize WIP and to enable production flexibility. The goal is to achieve a steady flow of material through the production process, and ensure the output of all processes is coordinated [7]. The only thing that seems to be missing, (though it's a big only) is a pull system for limiting WIP.

“The result of the combination of process flows and statistical control is a shipbuilding juggernaut which constantly "feels the pulse" of each process lane, which features constant problem-solving by all levels of the workforce and management, and which is constantly improving productivity” - The History of Modern Shipbuilding Methods: The U.S.-Japan Interchange

Like with the Toyota Production System, this method didn't necessarily require huge amounts of capital investment to implement. It could be implemented without expensive equipment or automation [8], and without new and expensive shipyards (the system was successfully implemented in many old Japanese shipyards [9].) Though there were certainly benefits from both of these, many of the benefits could be obtained purely from changing how the work is organized [10], and things like automation worked best when complemented these organizational changes.

Likewise, it didn't require a change in the output to larger volumes of identical products. Though there are again benefits from doing so, the studies stress that changes in organizational methods are capable of creating significant productivity improvements [11].

Shipbuilding vs construction

Efforts to improve construction productivity and reduce costs often center around figuring out ways to increase building uniformity and build large numbers of identical buildings. But shipbuilders were seemingly able to achieve increased productivity without this. So, is it possible to adapt similar methods to construction?

Depending on where you look, these methods have been used. To be sure, conventional construction very much resembles the "pre-improvement" state of shipbuilding - buildings are built in place one small piece at a time, proceeding subsystem by subsystem - first the foundation is laid, then the structure is built, then the building envelope, then the services are installed, etc. Work is performed with a lightly-specified set of drawings, requiring workers to use their expertise to fill in the gaps, and make on the fly adjustments as needed. Like with shipbuilding, it's a time consuming and labor-intensive process.

And even with modular construction, where a building is built up from largely fully outfitted 'blocks', the process often still proceeds in a similar fashion, just on a smaller scale - workers assemble each module one system at a time, starting with the structure, then installing services, then finishes, etc. Much of the work takes place inside the module after the structure is in place, requiring ladders, working overhead, etc.

But this isn't true of all modular construction. Consider, for instance, this video of a modular factory:

You can see the outlines of a process that’s similar to shipbuilding, where there are separate stations for each ‘zone’ (roof, floor, exterior walls, interior walls), some being built from smaller subassemblies, and each one getting several different functional systems (framing, drywall, insulation, some plumbing and electrical components) installed prior to being attached to the larger ‘block’. The facility has cranes sized to move the largest components used. Jigs and guides are used to ensure assemblies stay within tolerance. Work is even arranged to prevent the workers from having to reach overhead (at around 4:50, for instance, you can see drywall, electrical wiring and ducts being installed on the ceiling with the workers working above.)

So the question becomes, why aren’t these methods more widely adopted in the construction industry?

The obvious answer is that they don't reduce cost to the extent that they do in shipbuilding. But why not? What differentiates building prefabrication (where 'block' construction shows minimal cost savings) with shipbuilding (where it shows significant savings?)

I have a few suspicions.

One is that, unlike shipbuilding (where all the work can take place in controlled factory conditions), a significant fraction of construction work will end up needing to take place on-site. There will be site-specific foundation work, and the on-site module joining imposed by shipping limitations (you can only move a module so big over the road) limits the size of 'block' you can work with. On-site work is inherently more expensive than work that can be done in a controlled environment farther back in the process, and building construction necessarily has a lot of it. And building modules pay a 'tax' of transportation costs to the site that ships don't have to.

Even in the absence of transportation restrictions, block size would be limited by material - it's much easier to design enormous blocks that can be rotated and moved by crane if you're using steel than if you're using dimensional lumber.

Another one is that a building will be much simpler (and less expensive) than a ship. A large ship will have miles of piping, complex mechanical and electrical systems, and extensive machinery. The systems in most buildings (for instance, residential construction), are much simpler by comparison. The simpler your systems, the easier on-site installation work is, and the smaller the benefit from paying the design and coordination costs for planning out every assembly step. Larger, more complex buildings show greater emphasis on upfront coordination (they more commonly use design-build construction, and they're more likely to use prefabricated subassemblies (such as pre-built MEP racks.)

Material use affects this as well - the fact that it's so much easier to make in-place modifications to lumber than plate steel means it's likely less expensive to install things system-by-system in buildings than it is in ships.

On the other hand, even smaller simpler boats, such as fishing boats, still seem to use a subassembly-heavy construction method.

A third possibility is that the cost of rework, while significant for a building, is less than for something like a ship. A ship's hull, for instance, consists of carefully shaped pieces of steel - misalignment will require costly and difficult cutting to repair. Dimensional lumber, on the other hand is much cheaper, and relatively easy to modify quickly with power tools. And in many cases misalignment in building construction doesn't need to get corrected at all - a stud can be slightly shifted, for instance, without affecting the performance of the building, and its relatively easy (some would say too easy) to modify the structure to get services to fit. One piece of evidence for this is the resistance you see towards systems that would remove a lot of this slack, like advanced framing.

Buildings, especially residential construction, seem like they exist in a somewhat strange low-point in the optimization landscape. Their combination of size, (comparatively) inexpensive materials, high error tolerance, unavoidable on-site work, and simple design that means any more industrialized solution has a much different cost/benefit ratio than you see in other manufacturing operations. Even things that are similar on a number of different axes (such as ships) seem to end up with substantially different production economics.

These posts will always remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work and also gain access to a members-only slack channel.

Construction Physics is produced in partnership with the Institute for Progress, a Washington, DC-based think tank. You can learn more about their work by visiting their website.

You can also contact me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or by email: briancpotter@gmail.com

[0] - This is via wikipedia, which unfortunately doesn't cite an original source. But if you look at their helpful list of every Liberty Ship(!), that roughly tracks with how many were torpedoed.

[1] - Examples: The Marinship and Richmond shipyards both closed. Calship became a scrapyard. Swan Island was taken over by the Port of Portland and became a repair facility.

[2] Source here is "The History of Modern Shipbuilding Methods: The U.S.-Japan Interchange".

[3] The flow of materials into Japan had mostly been stopped, making the shipyards relatively useless in contributing to the war effort, and US planners predicted a need for ships for food shipments and to bring home Japanese troops, so the shipyards didn't get targeted for destruction. Source: "The History of Modern Shipbuilding Methods: The U.S.-Japan Interchange".

[4] - From 'The Progress in Production Techniques in Japanese Shipbuilding:

While I was analyzing in detail the complete sets of basic design drawings and engineering data for contemplated airplanes, which were supplied by the Navy, I noticed that engineering information and data issued by the engineering department were in full coincidence with the detail items for the production system. In other words, I was strongly impressed by the fact that all necessary information and data required for each stage of the production system, such as material flow, fabrication, sub-assembly, assembly, and final erection, were clearly described in detail sheets by breaking down the basic design drawings, which essentially deal with the finished product (that is, with the functional design of the airplane). Actually, this practice might have been a copy of the production system and the way of providing necessary information and data for production in the American automobile and aircraft industries. The idea that such a production system might be applied to shipbuilding was implanted in my mind, and this became a guiding principle in my study to prepare for the day when new shipbuilding at Kure might be authorized.

And "The History of Modern Shipbuilding Methods"

His study of Boeing's B-29 drawings disclosed how composite drawings are used to designate assemblies and subassemblies, each furnished with its own material list.

[5] - "The Reckoning" has some great Deming in Japan anecdotes:

There was one other thing that bothered the Japanese visitors: Americans' shameful ignorance of W. Edwards Deming. Deming was an American expert on quality control, and by the late fifties he had become something of a god in Japan. With the possible exception of Douglas MacArthur he was the most famous and most revered American in Japan during the postwar years. Beginning in 1951, the Japanese annually awarded a medal named in his honor to those companies that attained the highest level of quality. (Fittingly enough and typical of Deming, he himself supplied the prize money, from the royalties on his books, which, virtually unknown in the United States, were best-sellers in Japan.) Only an award from the emperor was more prestigious. But when Japanese productivity teams visiting America mentioned Deming to their hosts, the Americans rarely knew his name. The few who did seemed to regard him as some kind of crank. To the Japanese that was particularly puzzling, for when a Japanese team came to America and made the rounds, city after city, factory after factory, the one American all its members wanted to see was Edwards Deming.

[6] - From the National Shipbuilding Research Program's document on Line Heating:

The key to rapid construction is how to weld without distortion . . .“ said Elmer L. Harm, the former Kaiser manager who directed the 1951-1961 National Bulk Carrier shipbuilding effort in Japan. Japanese managers regard that venture as the starting point of modern shipbuilding technology. Locked-in stresses produced by forces needed to fit inaccurate parts were identified as a major cause of distortion. Line heating developments followed, aimed at both achieving better accuracy when shaping curved parts and removing distortion from subassemblies immediately after their manufacture.

[7] - One Japanese shipbuilding manager stated “In Japan we have to control material because we cannot control people.”

[8] - One exception here is the use of cranes. By enabling larger blocks to be moved and rotated, larger cranes allowed for increased productivity. From "Shipbuilding Innovation: Enabling Technologies and Economic Imperatives:"

Such preassembled units were actually very small by modern standards with assembly cranes of only 25–30 tons, compared to 1000 tons plus for a modern final assembly crane in large shipyard.

...the importance of large final assembly cranes to shipyard capacity and efficiency relates to the limitation of the amount of work undertaken at the final assembly site, which is relatively the most expensive stage of the process (prelaunch) due to problems of access and work orientation. The British Shipbuilders extensive productivity improvement program of the 1980s, conceived in conjunction with Louis D. Chirillo and IHI of Japan, estimated that the cost of a piece of work doubles once the block has left the workshops and that the same piece of work takes 8 times as many man-hours if undertaken at the final assembly site compared to at the early stage of the steel fabrication process and 12 times if undertaken postlaunch. Light cranes limit the size of block than can be erected from the workshops, thereby consigning more work to be undertaken at the final assembly stage. Light cranes also limit the extent of preoutfitting that is possible, outfit materials adding weight to the steel blocks. Large cranes mean that large blocks can be fabricated in workshops for erection into the dock, maximizing the potential for integration of steel and outfit work on the block, minimizing the amount of work left to the final, most difficult and expensive stages of the process. Fabrication workshops were designed specifically to support this strategy, defining the shape of a modern shipyard.

Modern blocks often weigh up to 3000 tons (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2092678218300220#bib4), and in some cases there have been blocks that approach 10000 tons in weight (https://www.marinelink.com/news/shipbuilding-hercules346140)

[9] - From "The Productivity Problem in United States Shipbuilding":

In 1979, a US team of six individuals with broad shipbuilding experience visited six Japanese shipyards to identify low investment, high return Japanese shipbuilding technology as part of the National Shipbuilding Research Program. Six Shipyards belonging to three different companies were visited. With one exception, all were old yards that had been modernized. Moreover, the visiting Americans noted that in the previous year the Japanese government requested that all shipbuilders reduce their facilities by 35 percent as a consequence of the world oversupply of tankers, that two of the companies visited had chosen to close new, modern yards in preference to the older ones visited, and that all companies had reduced employment at some of their new, large yards.

Officials of Exxon's Tanker Department have made comparative estimates of productivity and production cost among Japanese shipyards. Although acknowledging that the third generation Japanese shipyards have the highest productivity levels, they estimate that, because of the high equipment overhead costs in these highly automated yards, the maximum variation in total construction cost among the three generations of Japanese shipyards is on the order of 12 percent.

Regarding this last point, it's noted in "Ship Production, 2nd edition" that many highly automated shipyards went bankrupt or were nationalized in the late 70s shipbuilding slump.

[10] - From "The Productivity Problem in United States Shipbuilding":

Studies to identify the deficiencies in U.S. shipbuilding which can account for the large differences in productivity have tended to highlight certain modern methods and systems of shipbuilding which have been implemented abroad, but which have not been as rapidly adopted in the U.S. The systems and methods which have proven highly productive abroad are primarily organizational in nature, rather than technological or hardware-oriented. Effective planning and control of the process, not the use of technically complex manufacturing equipment, appears to be the key.

See also "Proven Benefits of Advanced Shipbuilding Technology -- Actual Case Studies of Recent Comparative Construction Programs"

One complication here is that capital investment in yard modernization does seem to be required if you want to build ships larger than the yard was originally designed for. Kang 2015 notes that old British yards were unable to produce very large oil tankers cost effectively (among other things, size constraints forced them to construct the ship in two separate halves, then join them.):

At Scott Lithgow, the need for a Goliath crane had arisen some years earlier when the company decided to abandon its upper building limit of about 150,000 dwt and equip to build ships of any size. It was clear that methods which were efficient on the existing berths could not simply be extended to VLCCs. There were two main reasons for this. First, Scott Lithgow’s biggest ships at that time were built by putting together prefabricated block units weighing not more than 85 tons. Too many block units of this size would be needed for VLCCs as fitting them together on the mat would be unnecessarily complicated, and far too many workers would be needed. A Goliath crane with greater lifting power would allow much larger units to be built on the ground, reducing the number of separate blocks to be assembled. Second, maximum throughput of steel depended to a large extent on long production runs on panel lines. Existing ships were built cross-section by cross-section, the crane retreating up the berth as each was finished. The crane could never return to an earlier section, because by then its rails were under the ship. This meant that the various parts that made up a section had to be made together. But a Goliath crane which spanned the entire berth and was free to move up and down could lay the bottom for the entire ship, or all the bilge units, or whatever happened to suit the production plan, instead of chopping and changing from one to the other. Longer runs and greater flexibility in production would become possible. With the Goliath crane spanning the new building mat from side to side, there was ample space not only for the ship itself but for large level areas beside it where the prefabricated units could be built up. Units of 85 tons came from the adjacent fabrication hall as before, but now could be assembled into much bigger units under the Goliath crane, to be lifted finally into place in one piece.

And of course facility size constraints were the reason NBC set up in Japan in the first place.

[11] - Increasing series production, however, would become important later, as described by Stott 2018.

I had always understood that the swings in the housing market disadvantaged the larger capital investment in modular factory fabrication, v. the labor-intensive site construction (i.e., workers can be let go during downswings but the factory must be paid for). Can you comment on the implication of market swings in shipping construction (global market) v. housing (local)?

Tradability is a large factor, too. You can have specialized shipyards (or car plants) ship to the whole world & reap the gains from that. Can't do that for prefab housing due to high transportation cost (and to some extent higher differences in the regulatory environment, esp. fire control, insulation, power line layout)