Lumber Price FAQ

Why wood has gotten so dang expensive

Lately the massive spike in lumber prices has been all over the news. Since it’s rare for construction issues to become significant enough that they penetrate mainstream publications, I thought it would be useful to put together a FAQ about what’s been happening in the lumber and building materials world.

What’s up with lumber prices?

Lumber prices are up, way up. The price per 1000 board feet is the highest it’s ever been by a large margin: over $1600 per 1000 board feet as of this writing, up from $400 per 1000 board feet in January 2020.

The price spike is affecting nearly every wood-based product. Prices for dimensional lumber, plywood, and OSB are all way up. My 2021 construction estimator lists a sheet of 7/16” OSB as costing around $12.00; the current price on Home Depot is nearly $40. And the price increase is nationwide - both southern yellow pine (used more in the eastern and southern US) and doug fir/SPF (used more in the west) show similar spikes:

In many cases, materials can’t be obtained at all. Construction schedules are being pushed out and materials are being substituted. Manufacturers are declaring force majeure as a result of being unable to deliver products. In some cases builders are refunding or cancelling buyers’ deposits as they aren’t able to predict when they’ll be able to obtain things such as cabinets, wall sheathing, windows, or roofing materials.

What’s the source of the price increase?

The price spike seems to be driven by a combination of increased remodeling/renovation and increased housing starts, which together make up about 70% of the demand for softwood lumber.

Home renovation is a significant user of lumber and wood products . Almost 60% of the lumber used in construction is used in renovation or remodeling, and Lowe’s and Home Depot combined make up over 50% of the building materials market (this might seem high until you remember that existing buildings outnumber new buildings roughly 100 to 1). And last year the home renovation market exploded: sales at Lowe’s and Home Depot were up over 20% compared to 2019.

Housing construction has also spiked: single family home construction is up 20% from January 2020 levels, which was already a 10-year high (though still below pre-financial crisis levels):

Interestingly, we don’t see a similar increase in multifamily construction:

The increased demand also shows up in home inventory levels (how many houses are for sale), which have plummeted.

However, lumber production hasn’t increased to match demand, hence the price spike.

Compounding these issues was the Texas Ice Storm in February, which knocked out roughly 80% of US polymer production. Because the storm occurred with very little warning, many factories weren’t able to shut down properly, resulting in polymers congealing and solidifying in the equipment. In many cases significant repairs were required before production could be brought back online, and as of mid-March only 60% of production had been restored.

In addition to drywall joint compound, PVC pipe, and dozens of other building products, polymers and resins are key components for the glues in manufactured wood products such as plywood, OSB, and gluelams.

Why hasn’t sawn lumber production increased to match demand?

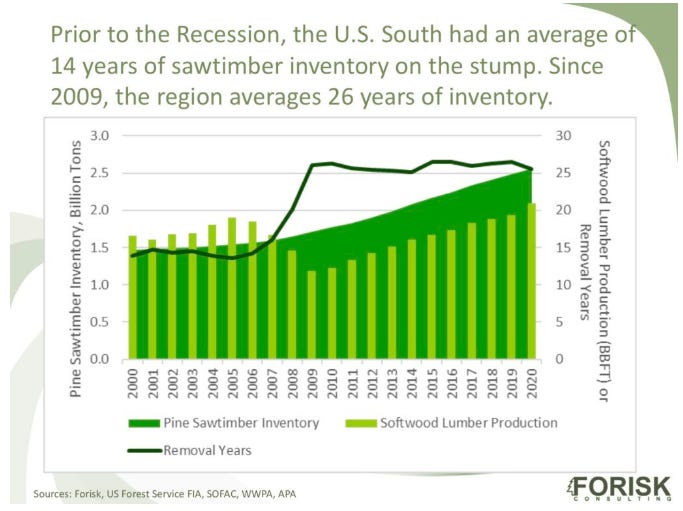

The bottleneck seems to be sawmill capacity - the price for finished lumber is way up, but the price for unprocessed logs is flat or even down. “Stumpage” (the price harvesters pay to cut down trees on a plot of land) is driven by the total inventory - how many trees are available to harvest. Post 2008, stumpage prices collapsed, and since then tree inventory has continued to increase:

Over the past year sawmill companies like Interfor, Canfor, and West Fraser have all seen enormous profits as prices have spiked, but their actual production volume is mostly unchanged:

Despite some reports, there weren’t huge decreases in lumber production as a result of COVID-19. Production stayed pretty close to flat:

Over the past 25 years the sawmill industry has seen a great deal of consolidation. Many mills closed, and production capacity declined significantly (though it has since recovered somewhat). The industry is increasingly dominated by a smaller number of large, corporate mill owners. These large milling companies will often acquire a mill, upgrade its equipment, and increase its production volume. These mills generally operate fairly close to their theoretical production capacity; even prior to COVID, sawmill capacity utilization was pushing 90%:

Can’t these mills increase capacity?

Most “mill capacity” numbers seem to be based on running two shifts a day, with the occasional third shift; it seems at least superficially possible that production could be increased by adding more regular third shifts.

In some cases, there have been reports that mills have been running third shifts, but are staffing them at reduced levels for COVID restrictions, and as a result are only getting two shifts worth of production (hence the flat production levels).

One possibility is that the bottleneck in the process is something other than labor availability. A good candidate for this is the kiln drying process. Lumber needs to be dried to less than 19% moisture before it can be used, a process that unassisted takes weeks or months. To speed up the process, mills run their sawn lumber through high temperature kilns to dry it out, but even with a kiln the process takes a significant amount of time - a day or more. If these mills are designed for balanced production, the kilns may only be sized for 2 shifts worth of production.

Additionally, a significant amount of our lumber comes from Canada, where the government owns the vast majority of forests, and must approve all harvesting plans. Mills don’t have the option of simply scaling up production.

Why aren’t new mills coming online?

They are, to some extent. Various new mills and mill upgrades are under construction by major producers, and mill capacity continues to trend upward. But a modern mill is a large industrial facility, costing tens of millions of dollars and taking years to design and build. Any mill project that was greenlit now wouldn’t come online for years.

What about smaller-scale sawmills?

Companies like Wood-Mizer make smaller mills that can be had for just a few thousand dollars. But these only produce somewhere in the range of 200-300 board-feet per hour. It would take roughly 150 of them to match what even a medium-sized mill can produce, and I’ve heard anecdotal reports that Wood-Mizer mill orders are backlogged for months. Even if you obtained one, the lumber would still need to be kiln-dried and grade stamped.

How does the lumber price increase affect home prices?

It drives them up significantly. Prior to 2020, lumber has typically accounted for 8-9% of the cost of construction (roughly $9 per square foot of construction). A 3 to 4-fold increase in lumber costs adds roughly $40,000 dollars to the cost of a 2500 square foot home.

Are we seeing price spikes and shortages of other building materials?

Yes, though it’s less pronounced than lumber. The price of steel is up significantly - rebar futures are at a 5-year high, suppliers are quoting extremely long lead times on things like steel joists, and builders are trying to get projects approved as fast as possible to lock in steel prices.

Concrete seems more mixed. Cemex just had their best quarter since 2007 on the back of strong residential demand, with US production volume up 9% over 2020. And anecdotally, I’ve heard from builders that concrete is becoming harder to get reliably. But US Concrete, another major concrete supplier, is selling at the same volume, and same price, as they were last year.

Lumber is correlated with residential construction in a way that differentiates it from other building materials. Steel is used in many different industries, many of which drastically curtailed production in 2020 (Nucor’s sales and volume were down in 2020, though they seem to be doing better now). Cement is used more in other types of construction than it is residential, which aren’t seeing the same boom that residential is:

But in general, building materials are experiencing across-the-board supply chain issues (one report from a major supplier listed interior doors as the ONLY product that could reliably be sourced without issues).

What’s driving the increase in residential construction?

Various reasons have been floated; low interest rates are a common one. But the most likely is that people are simply consuming a lot more housing than they were previously. The pandemic eliminated wide swaths of outside-the-home activities, caused many folks to work from home, replaced in-person classrooms with Zoom calls, etc. If you’re in your home twice as much, using it for more activities, and have more disposable income since you’re not going out, it makes sense to increase the size and functionality of your home. So folks are moving from dense urban areas to suburbs, remodeling their homes to add a deck or a home office, and trading up to larger places: 2 bedroom rents are up significantly more than 1 bedroom rents are.

Can’t we import more wood, or export less?

We’re doing both. Overseas imports were up just under 5% in 2020, and exports were down 17%. But outside of Canada, imported lumber is generally a small fraction of overall supply. In 2017, non-Canadian lumber imports were less than 5% of domestic production.

It’s difficult to ship lumber overseas cost effectively: lumber is (or was) one of the least expensive materials on the planet. At $300 per 1000 board feet (the average price over the last 25 years), a 20 foot shipping container holds just $4500 worth of material. The cost of transporting a container across the ocean is $1700 dollars or more.

Even if it could be shipped efficiently, there aren’t many places that could theoretically satisfy the demand. China isn’t exporting (their wood imports equal about 50% of US domestic production), and the only country other than Canada and the US that produces huge volumes of timber is Russia.

Even if we did have a ready supplier, it’s not necessarily straightforward to substitute different wood species into the US lumber market. The mechanical properties may be different (Austrian Spruce, commonly used in CLT production, has extremely low crushing values), and code restrictions may prevent it. The International Residential Code, for instance, lists specific species you’re allowed to use for various applications.

Can’t we use some other material for building homes?

Yes - things like masonry, concrete, and steel are all possible to build homes with. Lumber has long been the default as it’s by far the least expensive material to use. It’s also not straightforward to directly substitute any of those for an existing project; the entire house would have to be redesigned. And since other materials are seeing their own price spikes, lumber is often still a comparatively attractive option. But my guess is we’ll see more alternative material use on the margin.

Are we seeing other material price spikes in other countries?

Yes. Some places, like the UK and Canada, are seeing similar residential construction spikes and price increases. Others, like New Zealand, are seeing second-order effects from the spike in demand from the US and China.

How does all this end?

It’s unclear. Modern supply chains can’t pivot on a dime. The semiconductor shortage is expected to last into 2022, and US polymer production is expected to be down 15% for the entire year. In the short term, we should expect to see a continued increase in construction costs, which tend to lag material costs by 2 months or so.

Longer term, it’s hard to say. In some ways the lumber market is unusual - for other pandemic-induced shortages, such as toilet paper, we’ve often seen suppliers prefer to let stocks run empty rather than raise prices. Theoretically this should mean that the lumber market will eventually correct itself as new supply comes online to take advantage of the high prices. And if enough projects go on hold or get pushed out, this should also ease price pressure - the construction process progresses slowly enough that it would take a while for this to happen, but anecdotally it seems like it might be happening. A significant slowdown in multifamily construction, which doesn’t seem like it has the same demand spike but is a big consumer of lumber, wouldn’t surprise me.

But sometimes commodity price increases stick around. Consider iron ore (a key component of steel):

It was flat for many years, then spiked in 2008-2009 as Chinese consumption rose. That spike took 8 years to come back down, after which it immediately went back up. We’ve never returned to pre-2008 levels.

Theoretically timber production should be more flexible than iron ore production; it’s a lot easier to build a mill than to dig an iron mine. But it’s also possible COVID has shifted us into a new built environment equilibrium. Over the past century, a large part of human activity took place in office buildings, retail spaces, and schools - buildings that consume a lot of brick, concrete, and steel. If going forward more of this activity takes place in the home, we may see a sustained increase in homebuilding and lumber use.

Feel free to contact me!

email: briancpotter@gmail.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/brian-potter-6a082150/

"Concrete seems more mixed."

Brilliant as always.