Making Modular Construction More Modular

Plus: The Easyframe system, ACI committee on 3D printing, and cinder slab construction

Welcome to Construction Physics, a newsletter about the forces shaping the construction industry.

Making Modular Construction More Modular

Modular Construction vs Modular Assembly

Buildings are big. If we want to build them anywhere other than on a construction site, it requires building them in separate pieces, transporting them to the jobsite, and then attaching those pieces together. This is known as modular construction, and it has a few different flavors - if the modules are room-sized boxes, it’s called “volumetric modular”, if they’re individual panels it’s called “panelized”, if they’re made of concrete it’s called “precast”, and so on. It’s perennially the next big thing in construction.

Modular construction isn’t modular in the same way that say, a PC is modular. In a PC, each hardware function is isolated in a separate physical device - the hard drive is separate from the power supply, is separate from the CPU, etc.

A building's functions, on the other hand, are distributed throughout the entire building. Waterproofing, electricity, lighting, HVAC, structure, architectural finishes - they all run over the entire extents of the building, and generally can’t be isolated to a particular area. Sometimes these functions can’t even be separated from the site itself[1].

Typical modular assembly is modular by function - each function is contained in its own separate object. Modular construction is modular by form - the building is broken into separate pieces of manageable size, but each piece will contain elements of many different functions.

Building something out of separate functional modules has a lot of benefits. You can easily swap out modules as they wear out or as your needs change. Your product is easier to design, because your functions are mostly independent of each other. And your design gets done faster, because modules can be designed concurrently. It’s easier to build (just connect the modules together!) and easier to repair, because you don’t have to worry as much how changing one part affects another. You can often reuse modules between different products, thus gaining economies of scale in your production.

By isolating functionality in a specific module, you greatly simplify and reduce the number of interfaces between parts in whatever it is you’re building. The fewer interfaces you have, the fewer opportunities you have for things for things to go wrong - pieces not aligning, forces not transferring correctly, etc. The interfaces between components take most of the design and engineering work, and are one of the main sources of potential error. Modular construction greatly increases the number of interfaces between components. So while normal modular assembly makes design and manufacturing significantly simpler, modular construction makes them more complex, by splitting functionality across many different parts.

Modular construction has had its greatest market success in areas where this problem can be reduced or eliminated:

Parking garages are generally built using precast concrete panels. Parking garages are extremely simple buildings (almost no electrical, plumbing, or mechanical systems, no building envelope to keep the inside isolated from the outside, etc.) so the interface between modules is very simple.

Panelizers like Entekra use low level of completion panels that don’t have any services like electrical or plumbing preinstalled, which also keeps panel interfaces simple.

HUD manufactured homes are made of just 1 or 2 modules, reducing the number of interfaces between them.

Modular hotels or prisons can use a large number of nearly identical units, reducing the number of different interfaces required.

In “How Buildings Learn”, Stewart Brand advocates for a different sort of modular design, one based on grouping functions together in layers based on how frequently the underlying systems change, and having as loose a coupling between the layers as possible. The layers Brand suggests are Site, Structure, Skin, Services, Space Plan (partitions, etc.) and Stuff (furniture, etc). Site and Structure are “slow layers” changing extremely slowly or not at all over the lifetime of the building. But Services such as electrical or HVAC might be replaced several times over a building’s life, so are on a much faster layer. Keeping different layers as decoupled as possible makes it easy (and inexpensive) to update a building’s function as it ages, maximizing its usefulness.

The Retreat of Building Technology

Technology tends to make things lighter, smaller, cheaper, and more portable. As technology advances, it tends to shift building functions from slower to faster layers, culminating in them being removed from the building altogether, becoming just more Stuff[2]. A modern kitchen’s food prep function is provided using a series of appliances separate from the building, compared to a 1700s kitchen where cooking functionality would be part of the structure:

Some other examples of this trend:

Heating a building once meant having substantial infrastructure for handling and storing coal built into the structure.

Security systems increasingly are separate appliances, and don’t need to be wired into the house itself.

Computers, faxes and email eliminated the need for interoffice communication done via pneumatic tube services.

Prior to refrigerators, ways of keeping food cool would be built into the house.

Cell phones remove the need for any sort of inbuilt phone lines, intercoms or telephone niches.

Noise cancelling headphones and directional microphones reduce the need for buildings to give their occupants quiet, isolated spaces, making it easier to use open plan offices which require much less space per employee.

This is one reason why building technology appears slow to advance - sufficiently advanced technology doesn’t need to be part of the building anymore.

A tendency towards getting smaller and cheaper also means that as technology in large scale infrastructure advances, it can shrink down and until it can become incorporated into buildings in some fashion. Advances in information technology mean that a spare bedroom or desk in a home can handle all the functions of an office, which once took specialized equipment and people to operate it. As the car became ubiquitous, infrastructure for accommodating it (garages, driveways) gradually became incorporated into homes. As concerns about environmental impact and carbon footprint become more acute, and we scrutinize transportation costs more, we may see technology for local production (food, energy, consumer goods) increasingly incorporated into buildings.

[1] - I once worked on a project designed around using prefabricated foundations. A constant challenge was that the foundation is performing multiple functions - distributing the load of the building to the ground is one, but it’s also providing a level surface that can be built on. Prefab solutions all tended to require significant site work to get a level surface to build on, which you would get for free by using site-built foundations.

[2] - Two interesting exceptions to this are bathtubs and mirrors, which moved from separate pieces of furniture to effectively part of the building itself. Interestingly, these are also things that technology can’t really shrink, because their size is part of their function.

Elsewhere

Easyframe Saw

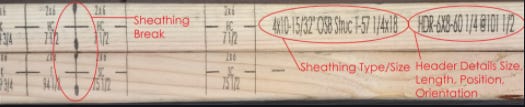

A saw that marks on your lumber where it goes in the building, what sort of sheathing you need to attach to it, etc. This is an interesting attempt at solving a problem that constantly plagues construction sites; getting the correct object put in the correct location. It’s unfortunately very common for say, column A to be put where column B should go, or to have a wall 3 inches to the left of where the plans indicate.

Part of this is due to the inherent difficulties in building something in a non-controlled environment, and part of it is the ease in which things get lost in translation between the construction plans and the building site. If you can remove that translation step by indicating correct placement on the building itself, you potentially remove an entire class of construction error.

You can also potentially build your building faster, as time spent figuring out where something needs to go is reduced. Constructing a building inherently requires switching between tasks frequently, which means a large number of setups - the time it takes to prepare before you can do a value-adding task like attaching a stud or setting a beam. Reducing the number of setups is difficult without completely changing how your building goes together, so the next best thing is to reduce how much time they take. Companies like Toyota have spent decades working on ways to reduce setup time.

Factory-based construction has techniques like laser projection available to them for this. Long term, I think this is an obvious use case for AR on construction sites - a set of glasses that would show you exactly where you needed to place your studs, run your pipes, nail your sheathing, etc - a sort of turn by turn directions for construction.

Links

ACI committee on 3d printed concrete - No committee report yet, but this is a good development. Building codes almost all outsource their requirements for concrete design to ACI, so an ACI committee report both makes it easy for engineers to specify something, and gives building departments an easy way to incorporate it into the code. In general. Increasing the pace at which standards setting organizations operate seems like potential low hanging fruit for improving building technology.

Concrete cinder slab - This is an interesting structural system for floors, that uses an ultra-low strength, non-structural concrete to provide a walking surface, with the actual load resisted by a series of catenary wires in tension. I’d never heard of it, but apparently it was incredibly popular in New York in the 20s through the 40s - the Empire State Building was built using it.

LEGO artist that makes some truly amazing sculptures of famous buildings and cities

Fun to see how much simpler parking garages are. Thanks.