In the New York Times, Ezra Klein investigated the recent Goolsbee and Syverson paper on construction productivity we recently looked at. Klein suggests that the stagnation in construction productivity might be the result of organized special interests increasingly leveraging their influence over various parts of the construction process. This shows up as more complex and difficult to accommodate regulations, and groups whose approval must be secured (often at great expense) to get something built. While all sectors display this to some extent, construction, by virtue of the number of stakeholders involved (local residents, politicians, zoning boards, etc.) might show it more than others. Here’s Klein:

…costs concentrate in the areas of the economy in which the number of groups that have to be consulted mount. From this perspective, the productivity woes in the construction industry don’t seem so puzzling. It’s relatively easy to build things that exist only in computer code. It’s harder, but manageable, to manipulate matter within the four walls of a factory. When you construct a new building or subway tunnel or highway, you have to navigate neighbors and communities and existing roads and emergency access vehicles and politicians and beloved views of the park and the possibility of earthquakes and on and on.

It’s not hard to find examples of this sort of extended stakeholder negotiation adding complexity and causing delay in the building process. I previously noted a high-rise project in Boston where five different government bodies simultaneously claimed jurisdiction over the site, resulting in millions of dollars spent on permitting costs. Offshore wind turbine construction in the US has been slowed down by lawsuits from residents and commercial fishermen, and the huge number of federal agencies that have jurisdiction over ocean resources – it can take 10 years of planning for an offshore wind farm before construction starts. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) often requires environmental impact studies that likewise take years to perform.

To see if this explanation makes sense as the reason behind low construction productivity in the US, we’ll take a look at it through the lens of single family home construction. While single family homes are not what most people think of when they think of “difficulty getting things built in the US”, they’re a useful starting point in looking at the problem of construction productivity. For one, the US builds an enormous number of single family homes - roughly a million per year as of 2022. Single family home construction is nearly 25% of all construction spending in the US (and if you add in owner-occupied renovations, which we can assume are largely single family homes, it's closer to 45% of total construction dollars). So purely in terms of dollars spent, the single family home is a large part of the US construction landscape, and thus a large part of any observed productivity problem. By comparison, New York spending on transit construction, which gets an enormous amount of attention, is roughly 0.6% of US construction spending. Single family home construction methods also have substantial overlap with US multifamily construction (they both largely use light framed wood framing), making single family homes a reasonable proxy for most multifamily construction as well (another ~6% of US construction dollars). Because of the US’s obsession with single family homes, there is also a lot of detailed, granular data on various aspects of their construction that we don’t have in other types of construction. We know, for instance, the average cost per square foot of a single family home, something that’s much harder to come by in other types of building.

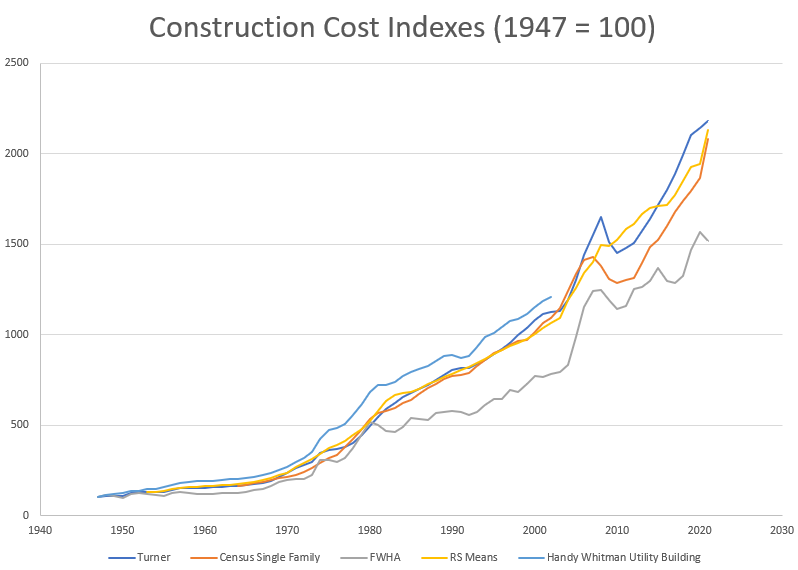

Single family homes also seem to show similar productivity trends as other construction sectors. When looking at “square feet per employee per year” Goolsbee and Syverson found fairly similar trends in single family and multifamily construction. The cost of single family homes also seems to increase at similar rates to cost indexes of other types of construction, such as commercial and utility buildings.

Mechanisms of cost increase

There are, roughly, two sorts of costs that special interest groups might inflict upon the construction process. The first are what we might call additional input costs – the burden in materials and labor that complying with various regulations requires. These costs are imposed by things like stricter building codes requiring greater amounts of insulation, hurricane clips so that high winds can’t tear the roof of buildings in a storm, and stronger shearwalls so that a building can survive an earthquake. OSHA rules which mandate additional safety precautions during the construction process also fall in this category. Recent OSHA rules on preventing exposure to silica dust, for instance, have increased the safety requirements (and thus the cost) of concrete cutting operations.

The second type of cost is the cost of delay that results from negotiating with various stakeholders, and jumping through the hoops that they require. Going back and forth with a zoning board, or the time spent performing an environmental impact study, would fall into this category.

The line between these two categories is sometimes fuzzy. For one, increased labor inputs often can be thought of as delay – if stricter safety rules mean that ironworkers take longer to set steel, for instance. For another, the same root cause might create costs in both categories. If I can only get zoning board approval for my new project after a lengthy negotiation in which I agree to add an expensive masonry facade, that’s an extra input (the facade itself) as well as a negotiation delay. Nevertheless, categorizing costs in this way broadly maps onto two things often blamed for low construction productivity - increasingly strict regulation, and interest groups who have the ability and the desire to veto a project.

Costs of delay

In Klein’s piece and elsewhere, much attention is given to the fact that getting things built in the US is often a difficult, protracted negotiation with numerous stakeholders. Here’s Klein again:

I ran this argument by Zarenski. As I finished, he told me that I couldn’t see it over the phone, but he was nodding his head up and down enthusiastically. “There are so many people who want to have some say over a project,” he said. “You have to meet so many parking spaces, per unit. It needs to be this far back from the sight lines. You have to use this much reclaimed water. You didn’t have 30 people sitting in a hearing room for the approval of a permit 40 years ago.”

Syverson likewise thinks the numerous veto points are a possible explanation:

This, Syverson said, was closest to his view on the construction slowdown, though he didn’t know how to test it against the data. “There are a million veto points,” he said. “There are a lot of mouths at the trough that need to be fed to get anything started or done. So many people can gum up the works.”

One way to test this explanation is to look at the actual hours spent physically constructing a building. If increased negotiations and veto point navigation were the source of the drag on productivity, we might expect actual construction hours to be decreasing (as technology gets better and methods improve), offset by more time spent on various stakeholder negotiations and costs.

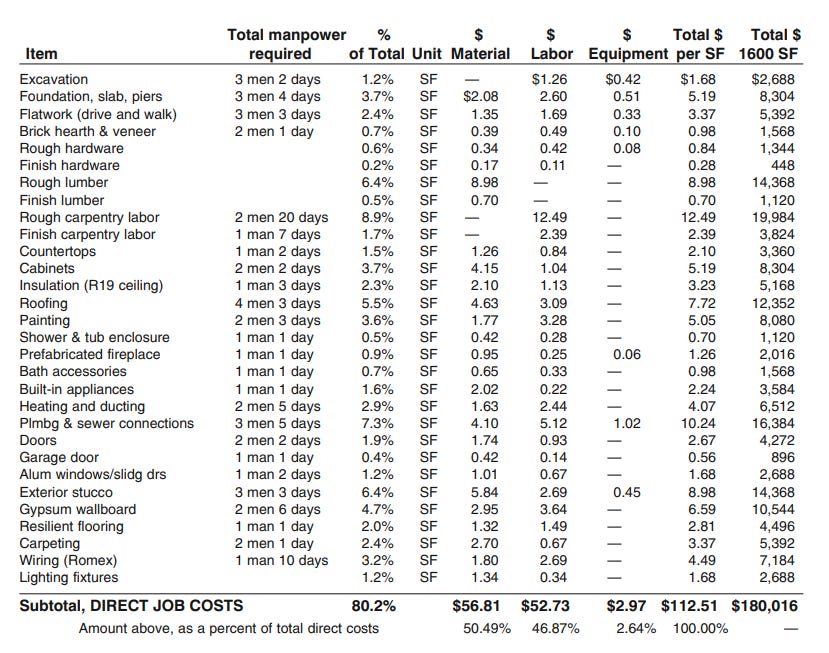

However, in single family home construction, this doesn’t seem to be the case. A 1969 BLS study of single-family home construction found that it took 85 on-site hours of labor for every 100 square feet of single-family home built in 1962, which by 1969 had fallen to 82 hours. If we add up the required on-site hours in my 2022 Construction Estimator, we get…86.5 hours. So over 50+ years, the number of labor hours required on-site to construct a single-family home in the US actually increased by about 5%.

These construction estimator costs are very close to the average cost per square foot of a new single-family home in 2021 as recorded by the census, which suggests that they’re accurate.

It’s still possible for these sorts of stakeholder delays to be showing up during the construction process, increasing the number of on-site hours required. Things like waiting for inspectors to show up, fire marshalls shutting down sites for non-compliance, or work stoppages due to permitting issues might be adding to the number of hours workers are spending on the jobsite. However, a survey by the National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) asked homebuilders about the costs of various regulations, and found that the average cost of regulatory delay on single-family home projects during construction was less than $1000, or about 0.25% of the overall sales price of a new home. So homebuilders, at least, don’t seem to think this is a substantial cost overall (though it’s possible this might look different in a high-interest rate environment).

(We’ll come back to this NAHB study shortly).

This isn’t that surprising to me. While construction does have numerous veto points that must be navigated, these mostly occur before construction starts, and thus we wouldn’t expect them to show up in the productivity statistics. Outside of single family home construction, much of this stakeholder navigation will be done by real estate developers, which aren’t classified as construction companies (and thus won’t show up in measures of construction productivity). Delays and stakeholder negotiations are a problem, but they’re a separate problem from construction productivity.

Additional inputs

The other way interest group influence would show up as increased construction costs would be increasing inputs during actual construction - more stringent regulations requiring stronger, more energy efficient structures, new safety rules creating more overhead, etc. If local jurisdictions have aesthetic requirements, such as needing some particular amount of masonry or glazing, or mandating certain roofing materials, that would show up here as well.

It’s clear that building codes and safety rules have steadily gotten stricter over time. The concrete code, ACI 318, was 142 pages in 1963. Today, it’s over 600 pages. The standard used for calculating loads on a building, ASCE 7, was 94 pages in 1988 and is over 1000 pages today.

Increasingly strict regulations have, among other things, made modern buildings safer and more energy efficient. But putting aside for the moment whether this regulation is worth it, can we estimate the cost of more stringent regulation?

The NAHB’s survey of homebuilders we mentioned earlier estimated that regulation was responsible for about 25% of the sale price of the average new home. But the survey only asked about the costs of the last 10 years worth of building code changes, and it includes many things that occur outside the construction process (like various permitting fees), making it an uneven measure of regulatory costs. I also suspect this estimate is biased upwards, since it’s based on builders' perceptions of regulatory costs. A similar survey for multifamily construction estimated the cost of regulation was 40% of a multifamily development, but it’s almost impossible for this to be anything except a wild overestimate. Can we do better?

Single-family homes are almost all built under some version of the International Residential Code (IRC), which is updated every 3 years. (It’s called the “International” Residential Code, and is developed by the “International” Code Council, but it’s essentially a US only code. See How Building Codes Work in the US for more.) For the last 15 years, the NAHB has analyzed the expected cost increase of each individual code change in every IRC update. Because construction will vary from site to site, and code some provisions affect some areas more than others, the NAHB does a “high” and a “low” estimate for several styles of home in different regions of the country.

This won’t be a perfect proxy for building code cost increases: some states will amend the IRC to make it stricter, other states will amend it to make it less strict. States will also vary as to when and if they adopt the updated versions of the code. But it will provide a reasonable approximation.

If we take the high and low estimates for each climate zone looked at, and convert them into a yearly average, building code regulation adds about 0.5% to the cost of a new home each year on average.

(Note: I’ve left out the estimated cost increases from fire sprinkler requirements, as very few jurisdictions have adopted those. I also just took the straight average of each climate zone rather than trying to weigh them by the amount of construction that takes place in each, but I don’t expect this would change the result much.)

An additional half a percentage point a year in costs would theoretically go a long way to explaining the construction productivity gap. If regulations add roughly 0.5% to the amount of inputs required to build a house each year, independent of size or features (most quality adjustments won’t capture these sorts of changes), that will show up as a productivity decline of 0.5%. And this doesn’t include other regulatory costs like OSHA compliance or jurisdictions requiring aesthetic changes (adding masonry veneer, etc.), which we might charitably estimate as another 0.5% annual cost increase, or 1% overall [0]. Seems like a lot!

However, construction isn’t the only sector in which regulations have gotten more strict over time. This has occurred in every sector of the economy. The Federal Register, a list of all rules and proposed rules by federal agencies, went from 2620 pages in 1936 to over 64,000 pages in 2018.

To explain the productivity gap between construction and the rest of the economy, it’s not enough for construction regulations to be getting stricter over time - they have to be getting stricter faster than in other sectors.

Is this occurring?

A full analysis of this is beyond the scope of this post, but we can perhaps get a sense of what the magnitude might be in other industries. A 2021 study of car regulations estimated that between 1967 and 2015, regulations for safety, emissions, and fuel economy (which are reasonably comparable to building code requirements) added about $6200 to the cost of a 2016 car. This works out to roughly 0.45% cost increase per year, fairly close to our average cost increase for single-family home building code regulations.

As we noted, there are other input cost increases to single-family construction besides code changes, but the same is true for other industries as well - that 0.45% doesn’t include the cost of OSHA compliance, or of environmental regulations that manufacturers must comply with. A 2014 study by the National Association of Manufacturers estimated that environmental regulations cost manufacturing firms on the order of $10,000 per employee per year on average.

Interestingly, our rough estimate of ~1% cost increase per year in single-family home construction caused by regulation (which would likely show up as a 1% decrease in productivity) is very close to a Mercatus center estimate for how much regulation slows down overall economic growth in the US - roughly 0.8 percentage points per year.

To be clear, all these estimates of regulatory cost are rough, almost certainly biased in various ways, and should be taken with heaping piles of salt. My point is that to be an explanation for the productivity stagnation in construction, regulation needs to be a much greater burden on construction than it is in other sectors, and it’s not obvious that that’s the case.

Other influences of regulation

Added inputs isn’t the only way that regulation might be affecting the construction industry. It’s also possible that overly strict regulations make it more difficult to adopt productivity-enhancing technology in the construction industry specifically. Klein doesn’t mention this thesis specifically, and investigating it more deeply is beyond the scope of this post, but I think this is a good place to look. For one, building codes in the US are often prescriptive, mandating specific building systems or materials, in ways that regulations in other industries aren’t, which might make it harder to adopt improved methods compared to other sectors of the economy.

Conclusion

So, to sum up, based on the data from single family homes.

Veto points and stakeholder negotiations, while a problem, likely aren’t the cause of construction productivity stagnation specifically.

The regulatory burden on construction is increasing over time, but it’s not obviously increasing any faster than in other sectors.

Of course, construction in other sectors might show somewhat different patterns here, and it would be worth probing further on these questions. But single family home construction is a huge part of US construction, and will be a big part of the construction productivity story any way you tell it.

When talking about overcoming difficulties of getting things built in the US, it’s important to be clear about which problem you're solving, and what’s needed to actually solve it. Difficult zoning and land-use rules, burdensome environmental studies, and NIMBYs blocking development via lawsuits and other methods are serious problems that make it harder to build things in the US. Low construction productivity also makes it harder to build things in the US than it would be if productivity were higher. But while there’s overlap between these, these aren’t necessarily the same problem, and won’t necessarily be solved in the same way.

[0] - This is based on the NAHB survey, which had building code changes as around $24,000 of the $52,000 costs incurred after construction starts. Based on the survey, some of that $52,000 will be things like impact fees which don’t really make sense to classify as construction costs (they certainly wouldn’t have any effect on on-site hours). So builders think that roughly half the cost of construction regulation is from recent code changes, half from other types of regulation. Estimating that other types of regulation are, at most, equal in magnitude to code changes thus seems reasonable/conservative.

“My point is that to be an explanation for the productivity stagnation in construction, regulation needs to be a much greater burden on construction than it is in other sectors, and it’s not obvious that that’s the case.”

This assumes the cost of complying with regulation is same for construction as for other industries which I do not think is the case. For a manufactured good or an large online service, the cost of figuring out how to comply is amortized over 1M or even 100M units. The impact to the bill of material is still paid by every unit but the substantial costs of understanding the regulation and engineering a solution are not as they are amortized over the whole production. For construction, the cost of understanding and figuring out how to comply has to be done for every single building.

Regulation compliance is absolutely harder for MF construction than for single family homes. Furthermore, single family homes have an inbuilt advantage of being more generally acceptable, at least in neighborhoods already zoned for them, which is more often the case than for MF construction, which often requires multiple layers of approval (here in New York City, that means the dreaded ULURP - Uniform Land Use Review Process - which can take a year or more, and pre-ULURP, which is basically unlimited, or until somebody's will breaks). In New York City, a major set of LSRD (Large Scale Residential Development) buildings was already at the foundation laying stage when it was challenged by a new New York Constitutional amendment guaranteeing clean air and water. This amendment wasn't voted in by referendum until AFTER the foundations were being laid, so neighborhood groups convince the judge to suspend construction while they argued the projects (3 towers, 4 developers) would violate the new amendment. While this delay takes place, the developers are losing millions, and one has already sold the lot to another developer (i.e. their will was broken).

Extra regulation is inevitable to some degree in a growing population, especially in cities - which residents of SF home communities fight like dogs not to join, in spite of the inefficiencies of suburbs over time - but when almost all groups are NIMBY, including many of the politicians elected, it's hard to see how anything developers or construction professionals can do, can counter that.

Also, even SF homes contain the result of countless regulations going into every component and facet of a home. Not all of this is bad: today's homes come with built-ins that weren't available in the 1960s, as well as safer electricals, plumbing, etc. (also, MORE outlets for all the stuff we plug in now). But it seems like some things have actually gotten worse: hollow doors instead of solid wooden doors, oversized windows and column-free rooms, weakening homes in the event of storms/hurricanes (are these more frequent due to climate change now, or are houses just built worse now? This documentary makes a case for the latter: https://www.thelasthousestanding.org/).

No one would take the chances workers took when they built the Empire State Building in 18 months, today, and such towers are both more complex and more regulated. It's certainly more than 0.5% extra time, when you factor in all the supply chained components.

I see there was a very sharp dropoff in regulations in your Figure 5 about the Federal Registry, in 2016, at the very end of the measured time period. Did construction productivity jump after that?