Reading List 07/12/2025

25 years of earthquakes, Google’s 2013 efforts to build a phone in the US, bear attacks in Japan, coal seam fires, and more.

Welcome to the reading list, a weekly roundup of news and links related to buildings, infrastructure, and industrial technology. This week we look at a map of 25 years of earthquakes, Google’s 2013 efforts to build a phone in the US, bear attacks in Japan, coal seam fires, and more. Roughly 2/3rds of the reading list is paywalled, so for full access become a paid subscriber.

Earthquake map

This very cool map visualizes 2.2 million individual earthquakes around the world, tracked by the US Geological Survey from 1998 to 2025. The vast majority (1.9 million) are small earthquakes with a moment magnitude – apparently the Richter scale isn’t really used any more — of less than 4 (equivalent to about 15 tons of TNT). Interestingly, the moment magnitude scale has a maximum of 10.6, the value at which “the Earth’s crust would have to break apart completely).

In the continental US the fraction of small earthquakes is even larger: of the 930,000 earthquakes tracked, only 3500 (0.4%) have a magnitude greater than 4 (possibly this is because the USGS has more thorough monitoring in the US, so picks up lots of small earthquakes that get missed outside the country?)

The pattern that jumped out at me here, other than the (expected) high level of earthquake activity on the west coast, is the number of earthquakes in Oklahoma, apparently due to fracking. (You can see a similar high seismicity spot that's likely due to fracking in eastern Wyoming.)

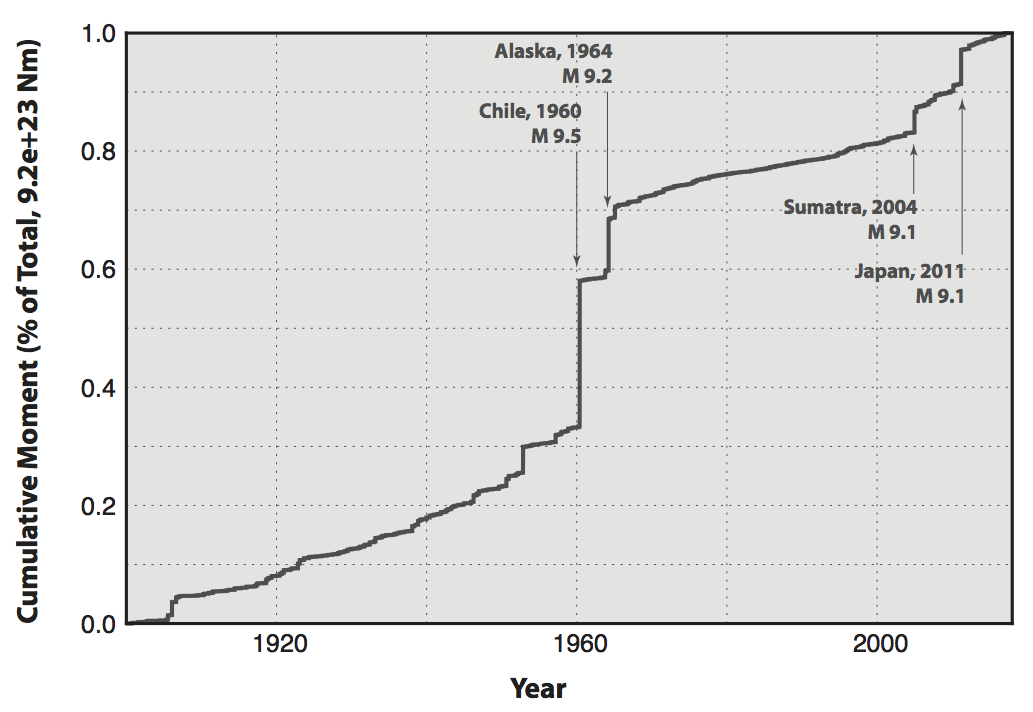

Related, looking into this brought me to the following graph showing total energy released by earthquakes around the world since 1900. As the website notes, “The small- and moderate-size earthquakes that occur frequently around the world release far less energy than a single great earthquake.”

Mount Rainier earthquakes

Also on the subject of earthquakes, earlier this week Mount Rainier, an active volcano in western Washington, exhibited a “swarm” of small earthquakes, though apparently this is in the expected range of normal behavior and doesn’t indicate an imminent eruption. From USGS:

An earthquake swarm began at Mount Rainier, Washington, at 1:29 a.m. PDT (08:29 UTC) on July 8, 2025. An earthquake swarm is a cluster of earthquakes occurring in the same area in rapid succession. Currently, there is no indication that the level of earthquake activity is cause for concern, and the alert level and color code for Mount Rainier remain at GREEN / NORMAL….

This swarm consists of hundreds of very small earthquakes with the largest so far being a magnitude 2.3 at 1:26 p.m. PDT (21:56 UTC) on July 8, 2025. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network has located 391 earthquakes as of 9 a.m. PDT on July 11; this number will increase as seismologists continue to analyze data. The earthquake rate has decreased over time, with a peak of 30 located events per hour on the morning of July 8 decaying to a few events per hour as of the morning of July 11. The earthquakes are mainly spread between 1.5-4 miles (2-6 km) beneath the summit. Earthquakes are too small to be felt at the surface and will likely continue for several days. There would be no damage caused by such small events.

Typically, earthquakes at this volcano are located at a rate of about 9 earthquakes per month. Swarms typically occur 1-2 times per year at Mount Rainier but are usually much smaller in terms of number of events. Earthquakes are one of several parameters we monitor to indicate what a volcano is doing. Right now, this swarm is still within what we consider normal background levels of activity at Mount Rainier.

The last large swarm at Mount Rainier in 2009 had a maximum magnitude of M2.5 and lasted three days. This swarm now surpasses the 2009 swarm in terms of total events, event rate, and energy release.

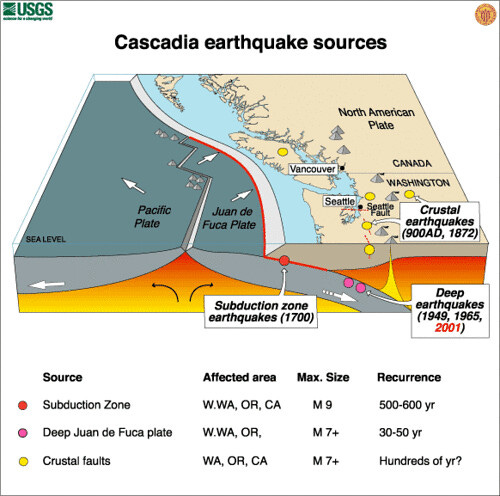

While this might not signal an upcoming eruption, it did remind me about the ongoing risk of a megathrust earthquake in the Cascadia Subduction Zone off the coast of Washington. From the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network:

At depths shallower than 30 km or so, the [Cascadia Subduction Zone] is locked by friction while strain slowly builds up as the subduction forces act, until the fault's frictional strength is exceeded and the rocks slip past each other along the fault in a "megathrust" earthquake. The fault's frictional properties change with depth, such that immediately below the locked part is a strip (the "Transition Zone") that slides in "slow slip events" that slip a few cm every dozen months or so. This relieves the plate boundary stresses there, but adds to the stress on the locked part of the fault. Below the transition zone geodetic evidence suggests that the fault slides continuously and silently at long term plate slip rate. From its surface trace offshore to a depth of possibly 5 km, all remote from land, observations are few and it remains unknown whether the fault is stuck or slipping silently.

Great Subduction Zone earthquakes are the largest earthquakes in the world, and are the only source zones that can produce earthquakes greater than M8.5. The CSZ has produced magnitude 9.0 or greater earthquakes in the past, and undoubtedly will in the future.

The last known megathrust earthquake in the northwest was in January, 1700, just over 300 years ago. Geological evidence indicates that such great earthquakes have occurred at least seven times in the last 3,500 years, a return interval of 400 to 600 years.

Austin Vernon on AI logistics

Friend of the newsletter Austin Vernon has a good post up on the potential impacts of AI on logistics. He makes the interesting point that because labor costs for manufacturing are already incredibly low for high-volume goods (since their production is already highly automated), advances in AI and robotics will have a much bigger impact on logistics:

Logistics robots will have a much bigger impact than production robots. The pure manufacturing cost in the phone case example might be $0.50. Most mass-produced products drive labor and capital expenditures to relatively small shares of production cost. A robot arm to load cases into containers or automatically change a mold might save a few cents per unit. It seems more likely that production robots will increase variety, shrink minimum scale, and compress development times. Low and high volume item costs can converge. Convergence has many interesting implications and benefits, but the cost floor will remain the same.

Similar to the production robots, the cost of shipping bulk goods via pipeline or ship won't change much. Humans are basically already out of the loop on these modes.

Intermediate goods traveling on pallets will have a significant cost reduction in transportation, even in the first-order scenario of automated trucks, forklifts, and electrification. Packetizing pallet movement with the "pallet hauler" bots will bring all shipments close to the cost floor without needing centralized logistics nodes.

The most dramatic changes come in the last-mile and parcel-size shipments. Human-centric logistics has always faced difficult tradeoffs between convenience and cost efficiency. Cost savings from slashing distribution centers and last-mile costs are two orders of magnitude larger than what production robots can do.

Google’s 2013 US phone manufacturing

Forbes has an article about Google’s efforts way back in 2013 to manufacture a smartphone (the Moto X) in the US. The upshot of the article is that while they got the factory up and running (with the phones being assembled from foreign-produced components), “made in the USA” didn’t end up being much of a consumer draw, and the phone didn’t sell well enough to justify the production line.

As the Fort Worth plant revved up, workers quickly started pumping out up to 100,000 phones weekly. Initially, the plant’s staff was overwhelmed, forcing Motorola to briefly backtrack on its promise to deliver phones to customers within four days. But over time, the volume dipped considerably. In the first quarter of 2014, Motorola sold 900,000 Moto X handsets worldwide compared to Apple selling 26 million of its new iPhone 5s during the same period, according to Strategy Analytics.

Five months after Moto X debuted, Motorola slashed its price to $399. After nine months, the factory was down to 700 workers, or less than one-fifth of what it had earlier.

Within the first few weeks, Randall said it was clear to leadership that the Moto X was underperforming. The team had to ramp down production.

More notable to me than the US manufacturing effort was the fact that Google apparently at one point purchased Motorola’s smartphone business (Motorola Mobility), then turned around and sold the company to Lenovo, both of which I had missed. (Motorola Mobility is apparently headquartered in Chicago’s enormous Merchandise Mart, formerly the world’s largest building at 4 million square feet).