Reading List 1/11/25

LA fires, self-driving tractors, an NRC lawsuit, faked endangered species, and more.

Welcome to the reading list, a weekly roundup of news and links related to buildings, infrastructure, and industrial technology. This week we look at the fires in Los Angeles, self-driving tractors, a lawsuit against the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, fake endangered species, and more. Roughly 2/3rds of reading list content is paywalled, so for full access become a paid subscriber!

No essay this week, but I have a very long essay about why skyscrapers became unadorned glass boxes coming early next week.

Los Angeles fires

The major infrastructure-related story this week is the fires that destroyed a huge portion of Los Angeles. This article from Bloomberg has a decent overview:

At least five blazes burned across the Los Angeles region early Thursday, with the two largest — in the coastal enclave of Pacific Palisades and the other bearing down on Pasadena — proving extremely difficult to control and pushing firefighters to their limit.

The fires, driven by hurricane-strength wind gusts, killed at least five people and and forced more than 100,000 residents to flee.

Officials are under immense strain to contain the fires, which have scorched some 27,000 acres, upending life in America’s second-largest city. Homes and businesses have burned down, schools and roads closed, air quality plummeted, and thousands of displaced residents searched for hotel space or sought shelter from friends and family.

One estimate puts the damage from the fires at more than $50 billion. This graphic from Twitter user Sean Feucht shows the scale of the damaged area compared to the Great Chicago Fire:

We’ve previously noted that wildfire risk is causing some insurers to cancel homeowners policies. This article from the LA times from April 2024 describes how many Palisades-area homes had their insurance cancelled by State Farm:

Last month, State Farm — the largest home insurance provider in California — said it would drop 72,000 property policies across the state amid a home insurance crisis. Of those, about 30,000 are home insurance policies.

Denise Hardin, president and chief executive of State Farm, explained the company's decision in a March 20 letter to Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara, stating that rate hikes that were recently approved by the Department of Insurance amid high inflation would be insufficient to restore the company's financial strength.

"We must now take action to reduce our overall exposure to be more commensurate with the capital on hand to cover such exposure, as most insurers in California have already done," she wrote. "We have been reluctant to take this step, recognizing how difficult it will be for impacted policyholders, in addition to our independent contractor agents who are small business owners and employers in their local California communities."...

In Pacific Palisades, according to the letter, 69.4% of the 2,342 policyholders — or about 1,600 — will lose coverage. In Brentwood, 61.5% of State Farm's 2,114 customers there will lose their policies, or about 1,300 non-renewals.

These cancellations are driven by a California law, Prop 103, that limits the ability of insurers to raise their rates. They have created a ticking time bomb in California’s state-backed “insurer of last resort”. From an EE News article from March of 2024:

California residents would be forced to pay billions of dollars to bail out the state’s insurer of last resort if a major wildfire hits, the insurer’s president warned last week in a startling admission that speaks to the growing cost of climate change.

The comments are the latest and perhaps starkest indication of how intensified disasters due to global warming are eroding the U.S. property insurance industry and shifting rebuilding costs from insurers to the general public.

In California and hurricane-prone Gulf Coast states, property insurers are retreating from risky areas, forcing people to buy coverage from state-chartered insurers that can impose surcharges on insurance policies statewide to pay claims.

The California FAIR Plan has been overwhelmed by a surge of new policyholders and would need to impose charges on millions of insurance policies of varying types throughout the state after a major wildfire.

This bomb has now gone off.

In other fire news, Climate scientist Patrick Brown has a long post on Twitter about the proximate causes of the fire:

These fires are being driven by a particularly intense Santa Ana wind event with gusts over 80 mph in many locations.

Santa Ana winds are a part of LA climate, and there is little evidence that climate change will make them worse. If anything, we expect Santa Ana winds to become less intense/frequent as the climate changes.

Fuels are also very dry in the LA area, as there has been almost no rain so far this fall/winter. There is little evidence that climate change would be responsible for a lack of precipitation like this.

And this 2021 article from José Luis Ricón discusses the broader reasons why California is so fire-prone and the history of wildfire in the state:

But in gauging the longer-term trend of what’s really happening with the fires, it’s necessary to go back much further. Data derived from written records from Cal Fire and the U.S. Forest Service dating back to 1919 show that wildfires, far from increasing, have actually declined over the last 100 years. And in fact the website of the National Interagency Fire Center previously noted that fires were at their very worst a century ago. (See data, research, and methodology for this article.)

The same trend can be seen in a review of three separate long-term wildfire data sources, which show that wildfires declined from 1919 to about 1996 and have ticked upward since then, but not to the levels of a century ago:

The data on the overall, century-long trend suggest that most of the 20th century represented an unusually low amount of fire, and what we’re seeing now is a return to the “normal” levels of fire of the early 1900s.

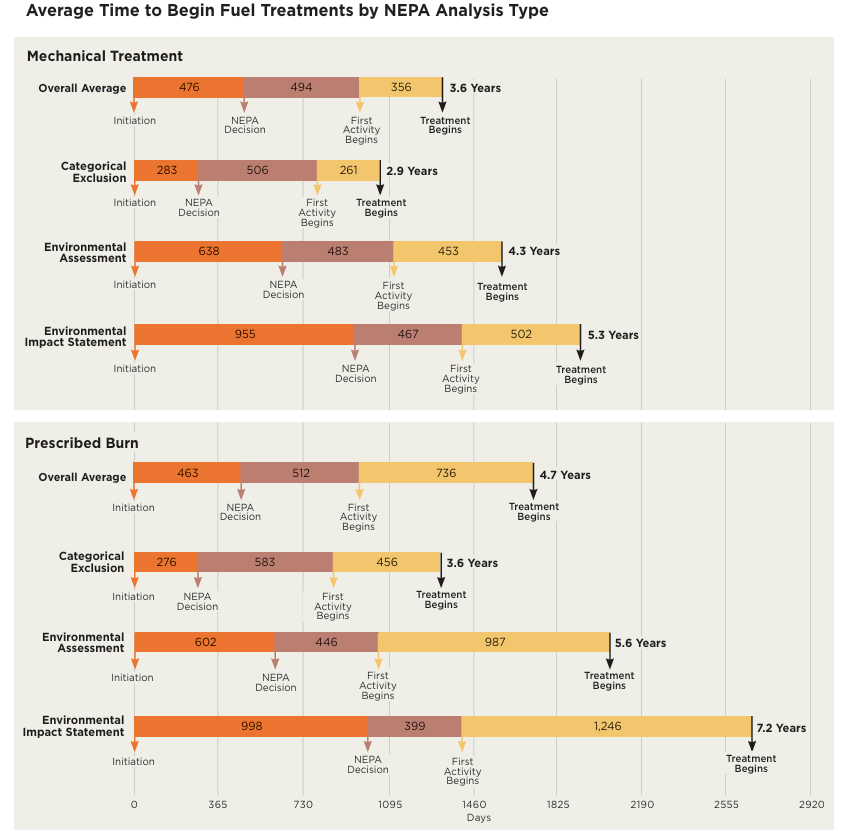

On wildfires more broadly, this report from PERC discusses how lengthy environmental review processes contribute to delays in prescribed burns:

Across all mechanical treatment projects, it takes an average of 3.6 years (1,325 days) to move from project initiation to start of treatment. For all prescribed burn projects, the corresponding time averages 4.7 years (1,711 days). For both types of project, it takes longer to begin the treatment as the level of environmental analysis becomes more rigorous. Similarly, the average time to complete NEPA review, displayed as the orange interval between Initiation and NEPA Decision, noticeably increases as the rigor of analysis increases.

Several commenters have stated that the high risk of fire means that we shouldn’t be constructing buildings out of wood in wildfire areas. I previously wrote about wood construction and the risk of fire here, and noted a study that suggests building with metal or masonry doesn’t seem to help as much as you might think:

Syphard 2017 studied over 1500 buildings exposed to wildfire between 2003 and 2007. While certain materials and details had significant effects on building survivability, wood in general wasn’t a significant factor. Interestingly, the most significant factors were structural density (number of houses per square mile) and structural age. Young, densely packed houses all survived. Old houses spread far apart were all destroyed.

Highway throughput

This WSDOT report has an interesting graphic showing the throughput of an interstate based on different vehicle speeds. There’s sort of a tradeoff at work, whereas as speed decreases traffic volume increases, presumably because following distances become shorter (or some similar effect); maximum throughput actually occurs at around 50 miles per hour.

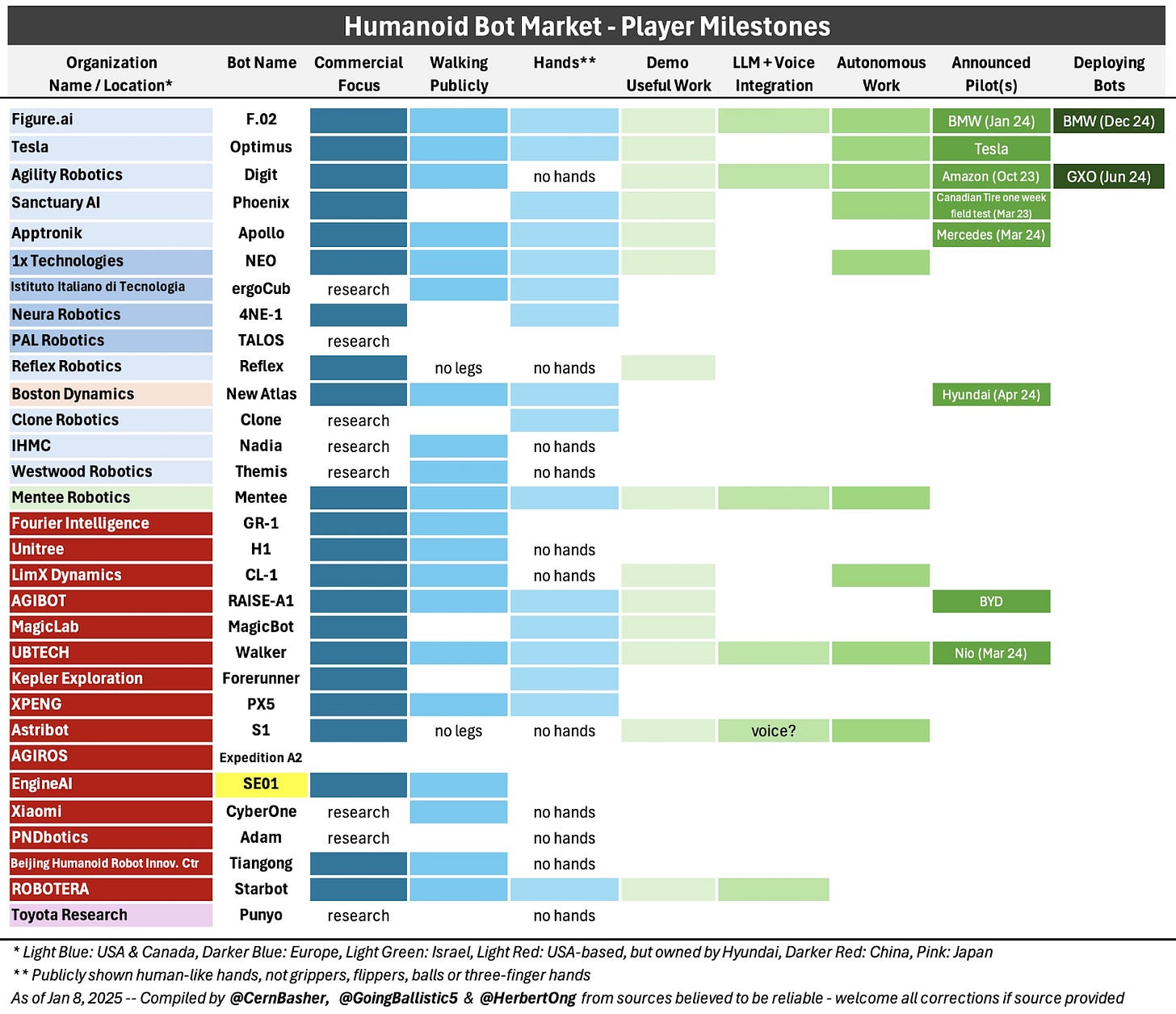

Humanoid robot progress

There’s currently a huge number of efforts dedicated to making a working humanoid robot. An easy way to keep tabs on these developments is this infographic made by Cern Basher, which gets updated every so often when new players enter the market and new milestones are achieved.

Self-driving tractors

In more automation news, John Deere is apparently working hard at developing a self-driving tractor. From The Register:

After unveiling its first autonomous tractor at CES in 2022, John Deere returned to Las Vegas to introduce four new autonomous vehicles and a second-generation autonomy kit capable of doing far more than tilling rows.

The new hardware, said CEO of Deere autonomy subsidiary Blue River Technology Willy Pell, will upgrade driverless Deere vehicles from plowing straight lines in open farm fields to navigating tight orchard lanes, quarrying, and mowing grass. Those new capabilities are thanks to enhanced camera arrays that extend the vision range from 16 metres to 24 metres, and Nvidia Orin GPUs that enable "full classification in milliseconds," Pell said.

The enhanced camera range means tractors can increase their speed by up to 40 percent - autonomously - and it also enable them to use wider implements.

"This new kit … will be able to do every job a tractor does on a farm," Pell said during a press conference at CES media day yesterday. "This will alleviate farmers from acute labor availability constraints throughout the entire year."

It doesn’t seem like this is available for sale yet — John Deere’s website describes it as “coming soon” and “being tested by customers in the field” — but it wouldn’t surprise me if self-driving tractors get widely deployed before self-driving cars do.

Industrial automation of lemonade

While robotics and self-driving vehicles are attention-grabbing, there’s still apparently room to run with more conventional automation technology. Bloomberg has an article about how Chick-fil-A automated its lemonade making. Previously squeezing lemons was done by hand at its individual stores. Now it all gets done in one large, automated factory:

Squeezing 2,000 lemons a day was such a pain for staff at Chick-fil-A Inc. that the company enlisted an army of robots to do it.

In a plant north of Los Angeles, machines now squeeze as many as 1.6 million pounds of the fruit with hardly any human help. The facility, larger than the average Costco store at roughly 190,000 square feet, then ships bags of juice to Chick-fil-A locations, where workers add water and sugar to whip up the chain’s trademark lemonade.

The automated plant frees up in-store staff to serve customers faster, according to the company. Squeezing lemons was a tedious task that added up to 10,000 hours of work a day across all locations and resulted in many injured fingers. Removing the chore aims to make working at Chick-fil-A more appealing – key for a company looking to add hundreds of new locations while contending with a fast-food labor crunch

The article talks about robots, but really this is a fairly traditional automation solution, the sort of thing that has helped bring down cost for the last 100 years. There are a few robots here and there (robotic guided vehicles, a few lifting arms), but most of the work is done by specially designed equipment repetitively performing the same motion.