Reading List 12/06/2025

3D printed legos, exploding wire detonators, the David Taylor model basin, multi-point metal forming, and more.

Welcome to the reading list, a weekly roundup of news and links related to buildings, infrastructure and industrial technology. This week we look at 3D printed legos, exploding wire detonators, the David Taylor model basin, multi-point metal forming, and more. Roughly 2/3rds of the reading list is paywalled, so for full access become a paid subscriber.

No essay this week, but I’m working on a more involved piece about international construction productivity that should be out next week.

A320 software upgrades

For the past several years most potential safety issues with commercial aircraft seem to have been with Boeing planes. But here’s one with the Airbus A320 family of aircraft, the most popular commercial aircraft in the world. Apparently a bug in a recent version of the elevator aileron computer (ELAC) software can cause issues if the data is corrupted by intense solar radiation. A recent JetBlue flight had an “unexpected pitch down” (sudden drop of altitude) because intense radiation corrupted flight control data. Via Aviation Week:

The issue affects around 60% of the global A320 fleet, including first generation A320s and the newer A320neo variants as well as A319s and A321s in each case. Most ELACs can be fixed by reverting to a previous version of recently-updated software, Airbus said.

But about 1,000 of the oldest affected aircraft need a hardware change to accept the new software. These airframes will need the old hardware re-installed--a process that will take longer.

Airbus identified the issue during its probe into an Oct. 30 incident involving a JetBlue A320. The aircraft, en route to Newark from Cancun, suddenly lost altitude while in cruise.

An A320 “recently experienced an uncommanded and limited pitch down event,” EASA’s EAD said, without identifying the specific flight. “The autopilot remained engaged throughout the event, with a brief and limited loss of altitude, and the rest of the flight was uneventful. Preliminary technical assessment done by Airbus identified a malfunction of the affected ELAC as a possible contributing factor.”

The aircraft had the newest ELAC software installed. Airbus determined reverting to the previous version eliminates the risk.

Average homebuyer age

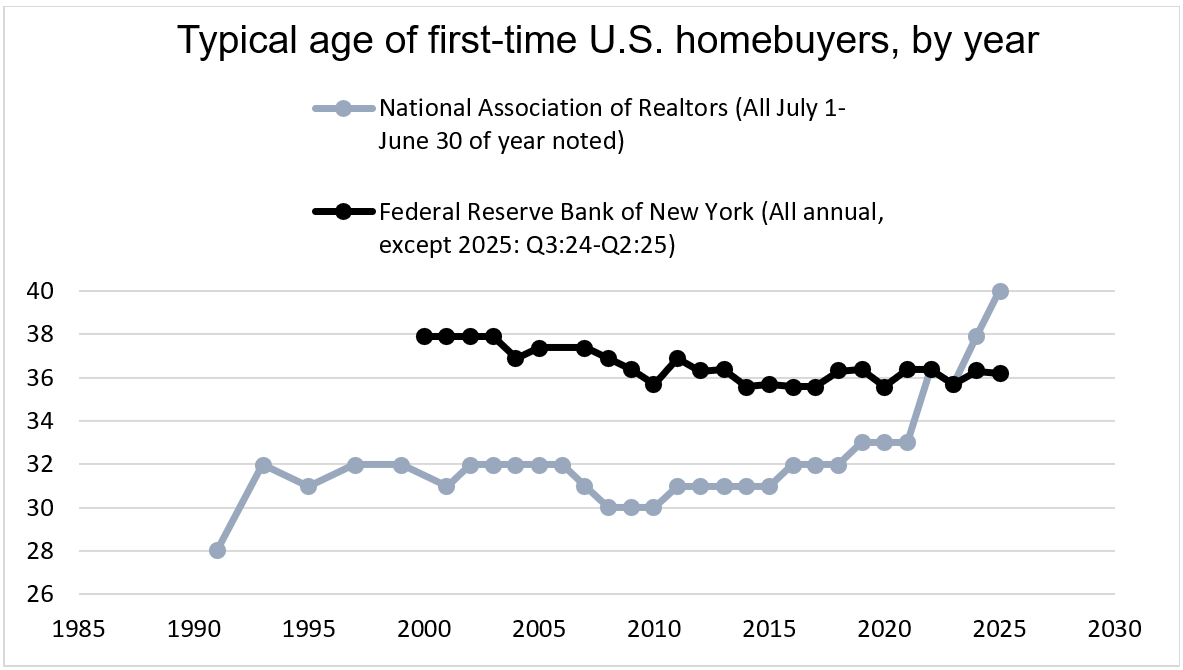

An oft-cited example of the increasing difficulty of affording a house is the steadily rising age of first-time homebuyers. Young people with lower incomes, the story goes, are being squeezed out of the housing market, driving the average age of first-time buyers up. Here’s a characteristic story earlier this year from the New York Times:

The path to homeownership continues to get longer, with the median age of first-time home buyers hitting an all-time high of 40 in 2025, according to a report from the National Association of Realtors.

“It’s kind of a shocking number,” said Jessica Lautz, deputy chief economist and vice president of research at N.A.R. “And it’s really been in recent years that we’ve seen this steep climb.”

In 1991, the typical first-time buyer was able to purchase a home by the time they were 28 years old. That number gradually climbed to 33 in 2020, then shot up to 36 in 2022 and 38 in 2024.

There are clear reasons behind the trend. Younger Americans are struggling to save for a down payment as they stretch their paychecks to cover student loans, a rising cost of living and, most critically, high rents, which make saving money harder. And even if they have saved diligently, a persistent lack of affordable housing inventory has left them shut out of the market.

However, it’s possible this is an artifact of how the data is collected (via mail-in surveys, which younger people may be less inclined to fill out). Homebuyer age data from the Federal Reserve indicates that, rather than steadily rising, average first time buyer age is declining over time. From the American Enterprise Institute:

NAR’s statistics are based on their annual survey of homebuyers and sellers. For the 2025 report, covering from July 2024 to June 2025, 189,750 surveys were mailed to a “representative sample” of buyers and sellers. However, only 6,103 completed surveys were received, indicating a response rate of just 3.5 percent, with only 21 percent, or 1,281, being FTBs.

The CCP, by contrast, is based on a 5 percent random sample of all credit reports, which reports provide both borrower age and home buying history. The CCP data, for the same period as the NAR, found the average and median FTB was 36.2 and 33 years old, both well under the NAR’s age of 40.

Digging deeper into the NAR and CCP results yields helpful distributions by age bins. While both have nearly identical shares for age 35-44, the NAR’s under age 35 groups are underrepresented by 17 percentage points and the aged 45 to 74 buyers are overrepresented by 18 percentage points respectively, compared to the CCP. The NAR bias to a higher age is perhaps not surprising given that it is a mail survey with 120 questions, which does lend itself to a high response rate by Millennials and GenZ-ers. The CCP data appears to offer a better historical view of the current position of FTBs (see graphic below). To reiterate its findings, FTB average and median age stood at 36.3 and 33 years for the period Q3:24-Q2:25, and there has been minimal FTB average age change since either 2001 or 2021.

3D printed legos

As I’ve noted previously, I’m interested in the progress of 3D printing technology, and how it might be extended to broader types of production — new types of materials, higher precision, printing complex mechanisms, lower unit costs making it more competitive for high-volumes, and so on. In this vein, Modern Engineering Marvels has an interesting story about Lego working for nine years to be able to 3D print legos for mass-produced sets:

The milestone capped a nine-year development program to develop a high-throughput polymer additive manufacturing platform able to reach consumer-level production volumes. Head of Additive Design and Manufacturing Ronen Hadar framed the accomplishment as LEGO’s equivalent of adopting injection moulding in the 1940s. The team’s aspiration wasn’t to replace moulding but to add to the design toolset – to make 3D printed parts “boringly normal” in future sets.

The production system makes use of EOS polymer powder bed fusion technology in the form of an EOS P 500 platform with Fine Detail Resolution. FDR uses an ultra-fine CO₂ laser that enables highly detailed features in nylon-based materials. The LEGO Group chose the process for its combination of dimensional accuracy, mechanical strength, and surface quality-all vital for parts to mesh properly with billions of bricks already in existence. Already, the company has doubled the speed of output from its machines and is looking for even more efficiency gains.

…From an engineering standpoint, this leap from prototype to mass production required the invention of new workflows. Unlike the decades-honed process control of injection molding, additive manufacturing had to come up with fresh answers for color matching and dimensional consistency, integrating current LEGO quality systems.

Filings coherer

Often the initial version of some particular technology is implemented in a way that doesn’t necessarily work the best or most efficiently, but is simply the easiest to get working. The gun-type bomb was chosen for the first atomic weapon because it was the most straightforward to build, but subsequent bombs used the more-complicated but more-efficient implosion mechanism. The first point-contact transistors were similarly eventually replaced with superior bipolar junction transistors.

Here’s another interesting example of one of these temporary technologies, the filings coherer, which was used to detect signals in the first radios. It consists of a glass tube filled with metal filings, connected to wires on either side. Initially, the metal filings have high resistance, limiting the flow of electric current. However, an electromagnetic disturbance — which can be induced by a passing electromagnetic wave — will cause the filings to “cohere”, reducing the resistance and allowing for greater electricity flow. Via Wikipedia:

When a radio frequency signal is applied to the device, the metal particles would cling together or “cohere”, reducing the initial high resistance of the device, thereby allowing a much greater direct current to flow through it. In a receiver, the current would activate a bell, or a Morse paper tape recorder to make a record of the received signal. The metal filings in the coherer remained conductive after the signal (pulse) ended so that the coherer had to be “decohered” by tapping it with a clapper actuated by an electromagnet, each time a signal was received, thereby restoring the coherer to its original state. Coherers remained in widespread use until about 1907, when they were replaced by more sensitive electrolytic and crystal detectors.

ElectroBOOM on Youtube has a good video where he looks at this “coherence” effect. And IEEE Spectrum has a good paper about the history of it — the mechanism behind it seems to have remained poorly understood until well into the 21st century.