Real Estate, Property Rights, and Negotiation

This newsletter is mostly focused on the mechanics of construction - how the parts of a building go together. But construction is just one part of the overall real estate development process, and the way real estate development proceeds has a large impact on construction. So I thought it would be useful to try to understand the mechanics of real estate, particularly with regards to what’s involved in putting up a building on a piece of land.

Real Estate and Property Rights

It turns out that the mechanics of real estate are deeply weird.

Our normal intuitions about property are that when we buy something, we own it, and can more or less do anything we want with it. If I buy a table, I can put it in my dining room, put it in my garage, chop it into firewood, etc. But this obviously isn’t the case with real estate - if I buy a piece of land, especially one that’s anywhere near an urban area, there are a huge number of restrictions on what I’m allowed to build on it.

One way to think about it is that in real estate, property rights are diffuse. With normal property, the rights for what can be done with it are all assigned to the owner. But in real estate, the property rights get spread around in a number of different ways; purchasing a piece of land doesn’t grant you complete control over it.

Many of these rights lie with various government bodies. Building codes, land use rules, and zoning laws are all ways that the government gets to decide what can and can’t be built. And unlike with typical laws, where there’s often an implicit assumption that people will follow them, putting up a building almost always requires explicit permission. Obtaining a building permit requires submitting your set of plans to the local permitting body, and getting their sign off, and inspectors will occasionally be sent out to ensure it’s being built in an acceptable way.

Other property rights lie with nearby residents. Almost every jurisdiction in the country requires some form of public hearing as part of the approval process for projects above a certain size. These meetings let the public air any potential concerns about the project, and which the local jurisdiction can require the developer address before a permit will be granted.

Other potential holders of property rights can be homeowners associations (via covenants or deed restrictions), utility companies (via easements), transportation companies (via eminent domain), or banks (via liens as part of financing agreements).

In addition to being diffuse, real estate property rights are fluid - they can shift and change much more than with conventional property, often in unexpected ways [0]. Building codes and zoning may change over time, or a new city council may get voted into office with different ideas about how development should proceed. In extreme cases, such as for properties that straddle the borders between various permitting bodies, it can be unclear exactly what the property rights are and who has them. During the development of the Museum Towers in Boston, five different permitting bodies simultaneously claimed jurisdiction over the site (the permitting costs ended up being more than $8 million in 2021-adjusted dollars). The frequency of lawsuits over development (one New York developer stated that 30% of their deals end up in court) is in some sense a reflection that with real estate it’s often unclear exactly who is allowed to do what.

In some ways ownership over a piece of land is much more akin to having a controlling interest in a company, rather than owning a physical object [1]. Even if you’re the majority shareholder, getting anything done often requires getting other shareholders on board, and where the control actually lies is something of an open question.

Real Estate and Externalities

The property rights of real estate are distributed like this because unlike typical property, where the benefits and costs are assumed to accrue entirely to the owner, the value of land is almost entirely determined by what’s around it. Schools, parks, amenities, transit access, adjacency to the beach or the mountains all make a plot of land’s value go up. Retail space in a high traffic area is much more valuable than retail space in the middle of nowhere, and a house right on the beach is much more valuable than the same house 3 blocks away from it [2]. A polluting or noisy factory, on the other hand, might make the value of adjacent real estate go down.

Land use rules and zoning provisions are a way of solving these sorts of externality problems [3]. By forcing certain sorts of development to take place in certain areas (ie: industrial and manufacturing in the south half of the city, residential in the north half) you can prevent negative spillover effects. And by including local residents as part of the approval process, you can make sure the externalities (both positive and negative) of a new building project are properly considered.

Property Rights and Negotiations

Unfortunately, the way these are implemented often leaves a great deal to be desired.

For one, zoning is often a blunt instrument. Single use, or euclidean zoning (the most common type of zoning in the US), allows only a single class of land use in a given area (just single family homes, just manufacturing, etc.) This sort of zoning screens off all the potential positive externalities of having many different types of establishment in one area (walkable cities, safer areas due to eyes on the street all the time, all the other stuff that Jane Jacobs talked about) and actually creates some negative ones, such as fostering car-dependence.

Another issue is that the benefits and costs of property development are distributed in an asymmetric fashion, in a way that governments and permitting bodies often have difficulty addressing.

Roughly, the costs of property development tend to be concentrated, and are mostly incurred by those living in the immediate area. A new building (especially something like a large multifamily development) can mean more traffic, less parking, more crowded schools, damage to the environment, blocked views, increased taxes to pay for infrastructure, etc. It also means disruption to the immediate area while the construction is going on.

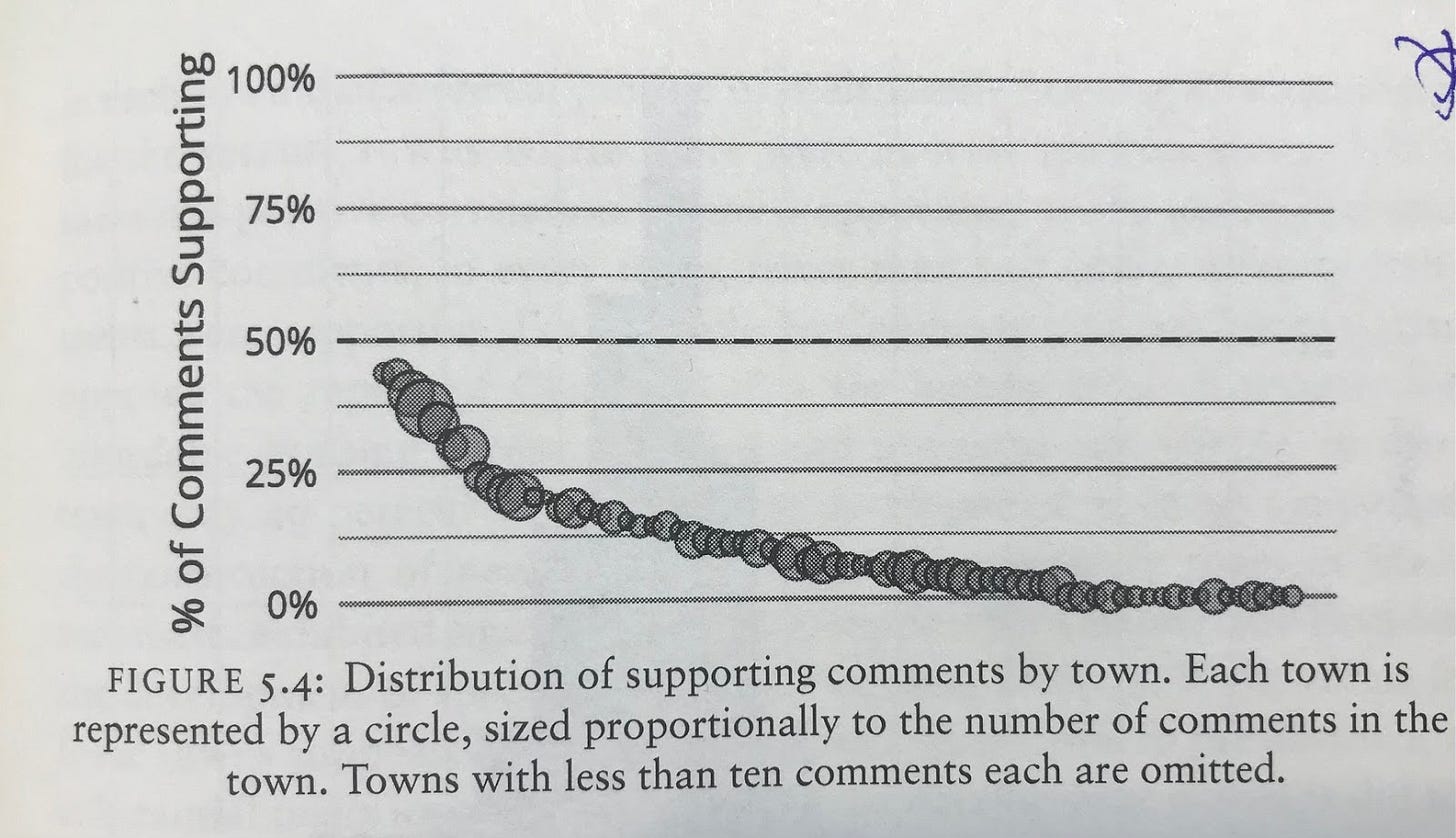

In essence, new construction has the potential to lower the quality of surrounding amenities/public goods, thus making the adjacent property a less nice place to live, as well as potentially lowering property values. All these effects occur disproportionately in the immediate area of the development - a new highrise across town has little effect on me, but one across the street is likely to have a noticeable impact. Comments from local residents in public meetings about new property developments thus tend to be overwhelmingly negative:

The costs of development accrue in such a way that local residents are often incentivized to expend a great deal of effort on resisting it. In Neighborhood Defenders, Katherine Einstein states that those objecting to development are disproportionately homeowners (more to lose from development, since their costs to move away are higher), and disproportionately elderly (if you don’t have a job and spend more of your time at home, keeping the immediate neighborhood to your liking is that much more valuable to you).

In addition to this, many of these costs can scale up depending on the wealth of the surrounding community. If I make $50,000 a year I may value an unobstructed view from my apartment window at $1000. If I make $5,000,000, I may value it at $100,000, and it becomes worth it to go to extreme expense (filing lawsuits, etc.) to try to prevent new construction that might block it. You can see a potential vicious cycle here, where lack of development drives home prices up, which are only affordable to wealthy people, and the wealthy people are incentivized to continue resisting development because of how much it will cost them personally.

The benefits of development, on the other hand, tend to be diffuse - a slight decrease in housing costs, a slight increase in urban area productivity due to agglomeration effects, a slight uptick in tax revenue for the city, a marginal increase in the number of niche amenities that become more feasible with more people [4].

The benefits also tend to accrue to people that the approval process doesn’t take into account. For instance, I live in Atlanta (OTP, but still), a sprawling metro area consisting of several different permitting jurisdictions. A new apartment complex in one of them (say, Brookhaven) will ease rents not just in the immediate area, but in the rest of the Atlanta metro area. Future residents of Brookhaven that the construction of new housing will allow also benefit. An approval process that only solicits feedback from current local residents won’t take any of this into account.

The result is that rules designed to prevent negative externalities of development disproportionately weigh the potential downsides, and decisions about what to build on a given piece of land tend to be somewhat one-sided negotiations - local residents trying to limit development as much as possible, and developers gradually reducing the extent of construction (200 apartment units down to 120, a 5 story building down to a 3 story building, etc.) or offering enticements (including more affordable housing units, adding green space, upgrading nearby intersections) to try to appease them. Residents can’t generally outright prevent new construction, but they have a variety of methods at their disposal for restricting it, such as filing lawsuits, or requesting time consuming and expensive studies (traffic analysis, environmental impact reports, etc). In extreme cases, residents have successfully lobbied local governments to purchase property purely to prevent it from being developed.

This is exacerbated by the fact that land has a) a relatively fixed supply and b) is immovable. For any given piece of land, there may be few or no other pieces of land with similar properties available - if I’m building an office complex that I want close to, say, Raleigh, Durham, and the research triangle, at least 10 acres and adjacent to a highway, there may only be one lot that meets that criteria. The larger and more complex the project, the more of a problem this becomes - if I’m building a gas station or a McDonalds, there are plenty of possible locations. If I’m building a large apartment complex, there are many fewer. A developer may have little choice but to keep adjusting the project until the neighbors will acquiesce (especially because a developer may have already invested significantly in the project by the neighborhood approval stage). This can mean going back to the development board multiple times with different plans for the site, structural arrangements, etc.

Part of the issue is that permitting is almost always handled at a very local level. Theoretically, a state government would have greater incentive to properly weigh the costs and benefits, but local governments tend to resist this sort of interference. While local permitting bodies stand to benefit from increased development (increased tax revenue, easing housing cost pressure, etc.), they’re also beholden to the interests of the current residents (city officials may have been elected on “anti-growth” platforms; if not they must consider whether someone on such a platform might run against them).

Real Estate and Construction

What does this mean for construction? It all pushes against being able to sell a uniform, mass-produced product [5]. Not only does a building need to take the specifics of the site into account (maybe one site has good east facing views, while another has good west facing views, requiring a different window arrangement), but the nature of the building itself has to evolve as part of the negotiations between a piece of property’s “shareholders”. The developer may be forced to reduce its footprint, reduce it’s height, change its exterior appearance, rearrange the interior, move signage, or any other number of things as part of securing building approval. A uniform product with few things that can be changed means fewer ways for the developer to appease local residents and zoning boards, making it harder to successfully close a deal [6]. And because of the hyper-local nature of real estate, a developer needs to be able to tailor their “product” (the building and it’s amenities) to the needs of the local market.

The result is that we see a particular sort of repetitiveness in building designs. Many developers do in fact have a variety of standard, off-the-shelf plans that they repeatedly build. But those plans go through the normal permitting process, and are adjusted based on the specifics of the site and what local zoning/ordinances/resident response requires

Alternatively, for multifamily construction, a developer may have a standard set of apartment floor plans that they use, but will be arranged in different building configurations on a project-by-project basis.

This was something that was a substantial constraint at Katerra - there was a constant tension between products that were uniform enough to achieve production economies of scale, but customizable based on individual developers' needs. In practice our “standard” products ended up having hundreds of possible variations.

Conclusion

So, to sum up: Real estate property rights are diffuse, where groups and individuals other than the landowner have a great deal of say over what gets built. The result is that real estate development is a complex negotiation between various stakeholders. This can make it difficult to do repetitive, uniform buildings that can be mass produced, as a developer will likely need to make adjustments to the building as part of closing the deal to get construction approval.

[0] - Prior to the invention of air travel, land ownership meant owning the entire column of air above the land. This changed to somewhere below 500 feet (the exact number is unclear).

[1] - Some real estate theorists argue that a piece of real estate is best thought of as a business. Developing it is akin to creating a new product that will compete in the marketplace, and it requires ongoing effort to make sure your product stays competitive (renovations, upgrades, marketing to attract users, etc.)

[2] - These properties of real estate are what makes a land value tax so compelling, as it’s supply is fixed (so taxing it can’t distort the market for producing it), and because the value of land is determined by what’s around it, not by anything the landowner does.

[3] - There are other ways of solving these problems, such as Coasean bargaining or having a single landowner for all real estate in an area, but they have their own drawbacks.

[4] - This terminology sometimes gets flipped - the concentrated benefits to the homeowner who protects their property value, and the diffuse costs of slightly higher rents by preventing development, etc.

[5] - Periods in the US with repetitive, mass-built housing, such as Levittown or 1950s California, had much more power concentrated in the hands of the developer, and there was less zoning and less ability for local residents to impact development.

[6] - It seems difficult to overstate the degree with which real estate development is synonymous with negotiation and closing deals; one book I have on real estate has an entire chapter just on negotiation. They’re central to the point that developers will sometimes refer to buildings as “deals”, as in “oh, our company is building two deals outside of Phoenix”.

Wow something I actually know about as someone not in construction who still finds your writing fascinating.

One of the biggest problems that leads to the complexity and the cost of planning to developers is the lack of uniform zoning/planning law. In my state zoning/planning is a local government responsibility and so every council has different zoning regulations. In my state that’s 79 different regulations. My local regulations are just under 1200 pages with 50 pages of amendments. As councils are elected often new councillors want to leave their lasting stamp on the area and write new zoning rules. This adds a ridiculous legal cost for developers because of local knowledge/expertise.

Lastly something to stress is the time cost as well. The average time to process the median planning proposal is 96 days where I live (most of which are small residential renovations: ie kitchens / added garage /new driveway etc). Skyscrapers are obviously far far longer. The bureaucracy of the planning commissions are infuriating. They only started accepting electronic planning applications LAST YEAR in some places due to Covid which is absurd since it’s been commonplace in the courts for at least 10+ years in most things. On appeal to the administrative tribunal 50% of appealed planning decisions get overturned (basically a coin flip!)

For all your articles about how construction is resistant to change, the Legal industry might give it a run for its money!

Thanks for the great work!

One thing that was not addressed is the perverse incentive that residents have not only to limit development, but to strongly skew it towards unaffordable, luxury units because it improves the future value of their own lots. Social or affordable housing is the very cancer they are trying to avoid, because it will bring the less well to do outsiders in the area, depressing "property values", and killing "community character", also know as "whiteness".

So even if highly efficient fabrication methods are developed, they will be up against communities that hoard land and deliberately restrict themselves to compete on the upper-middle class market. Any construction savings, even substantial ones, say 50k for a single family home, will be eaten away by some extra bathroom or some 2 acre minimum plot ordinance, designed to make sure that no house are made available in the area for less than 500k.