The Blast Furnace: 800 Years of Technology Improvement

The modern world uses shocking amounts of steel. In the US, we make roughly 575 pounds of steel per person per year. At the peak of US steelmaking in the late 1960s, it was closer to 1500 pounds per person, which is roughly how much China makes now.

Modern steel is produced by two different methods. The first uses an electric arc furnace to melt recycled steel scrap. The second method is to make new steel out of iron ore. While new steel can also be made in an electric arc furnace via the direct reduction route, most new steel starts life in a blast furnace. Iron ore (largely iron oxide), coke (coal that has been heated to drive out impurities), and limestone get placed in the furnace, where the coke reacts with the iron and air to form a high carbon iron known as “pig iron” (so named because historically the iron flowing down a trench into a series of casting molds resembled a pigs suckling from a mother sow). That pig iron then goes through a refining process (today a basic oxygen furnace, historically other methods such as open hearth furnaces or Bessemer converters) which reduces the carbon content and turns it into steel. [0]

Because steel can be recycled, and because the US has been making huge amounts of steel for over 100 years, we get a proportionately large amount of our steel — around 70% — from scrap steel remelted in electric arc furnaces. But this is a relatively modern development. Production of electric arc steel didn’t surpass blast furnace-basic oxygen steel in the US until the early 2000s, and worldwide, 70% of steel starts life in a blast furnace.

The electric arc furnace is a comparatively modern invention. It was first patented in the late 1800s by William Siemens, but didn’t see commercial use until the early 1900s when electricity became widely available and less expensive. For the first half of the 20th century, the electric arc furnace was largely used to make relatively small amounts of high-quality tool steels, replacing the expensive crucible process. It didn't start to produce steel in large volumes until the development of the minimill in the 1960s.

The blast furnace, on the other hand, has been in use for centuries. The earliest blast furnaces in Europe date to the 1100s, and for hundreds of years blast furnaces have been the primary way that our civilization has made iron. The blast furnace has been described as "one of the half-dozen fundamental machines of industrial civilization."

A common model of technology improvement is the overlapping S curve — when a new technology is created, it initially improves slowly while the bugs get worked out and the best way to use it is discovered. Eventually, it begins to improve more quickly, plateauing at some natural performance ceiling. It then gets replaced by a successor technology on its own S curve with a higher performance ceiling. With steel-making, for instance, we saw the crucible process get (mostly) replaced by the Bessemer and open hearth processes, which got replaced with the basic oxygen process.

This is a reasonable approximation of technology development, but there are many complicating factors [1], one of which is that the improvement phase might last for a very long time. The blast furnace is one of these technologies. The modern blast furnace works in the same basic way that a medieval one did, but it’s been improving, in fits and starts, for centuries.

The blast furnace does not have a heroic story of invention behind it. The original inventor, if one ever existed, has been lost to history. And outside of a few notable exceptions, the vast majority of its improvements can’t be traced to any one person. They were the result of countless engineers, mechanics, and craftsmen gradually making changes, accumulating improvements bit by bit in what Robert Allen describes as “collective invention.”

How a blast furnace works

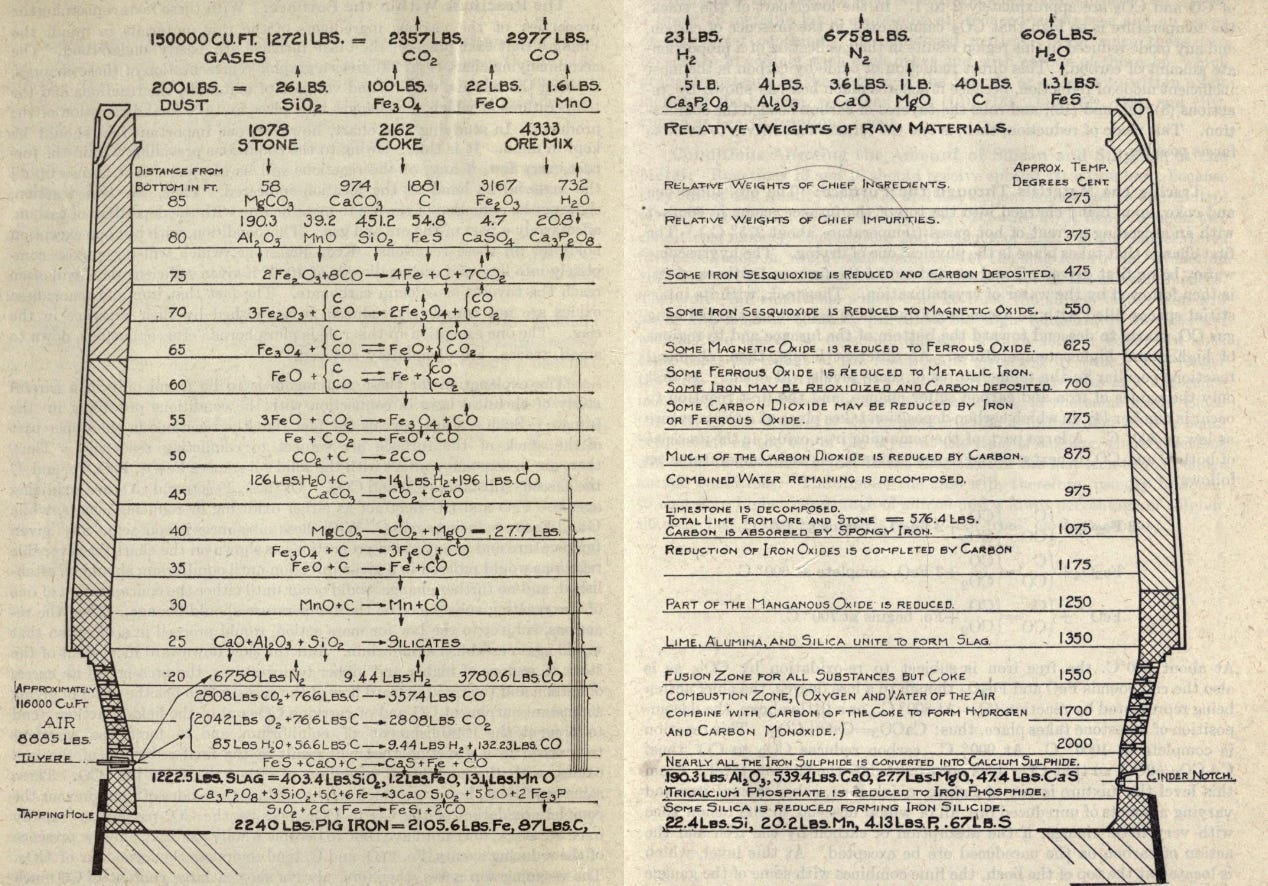

A blast furnace is, at its heart, relatively simple. It consists of a hollow, tapered structure, lined on the interior with a heat-resistant material called a refractory. Iron ore, a source of carbon (such as charcoal or coke), and limestone, together called the “charge” or “burden,” get placed in the top of the furnace, and air is blown in from the bottom through nozzles called “tuyeres.” The carbon both acts as fuel to heat the furnace, and as a chemical reactant: the oxygen in the air reacts with carbon in the coke to form carbon dioxide, which in the heat of the furnace quickly becomes carbon monoxide. The carbon monoxide, in turn, reacts with the iron oxide to form iron and CO2 (called “reduction” of the ore). The iron absorbs carbon, which lowers its melting point and causes it to melt as it descends into the hotter parts of the furnace. The now-liquid iron drips down to the bottom of the furnace where it’s drained out (called “tapping” the furnace). The limestone (CaCO3) reacts with impurities in the iron, such as silica and alumina, to form a liquid slag, which floats on top of the iron at the bottom of the furnace and gets skimmed off as it builds up. [2] Today, pig iron is mostly converted into steel, whereas historically it would have been converted either to wrought iron (in a finery or puddling furnace), or used directly as cast iron.

The early blast furnaces

The first blast furnaces in Europe date to Sweden in the late 1100s. These may have developed from bloomery furnaces, the previous technology for ironmaking. As a bloomery furnace got larger, it would have gotten hotter, which would have changed the reactions taking place and produced a liquid, high-carbon iron instead of the semi-solid, low carbon iron that the bloomery produced. But it’s also possible that the blast furnace was brought to Sweden from China via the Mongols. By the time it arrived in Europe, the blast furnace had been used in China for centuries, and by the 1100s China was producing on the order of 1.4 kilograms of pig iron per person per year.

In either case, over time, these early blast furnaces were gradually improved to produce more iron with less fuel:

…it would have been found that fuel could be saved by using a taller furnace to give a larger residence time in the strongly reducing conditions. Following the construction of larger furnaces, it would have been found that working needed to be continuous. Intermittent working, as used with bloomery hearths, would have been out of the question as there would have been too much heat and material bound up in the process, so that it would be uneconomical to stop it after each batch of iron had been tapped. It would also have been clear that a constant supply of water was more important than quantity, and small streams with a constant flow would have been more sought after than large irregular rivers. Ponds would have been built to regularize the flow in areas where rainfall might have been interrupted by summer drought.

— A History of Metallurgy

Similarly, at some point it was found that adding limestone as a flux increased iron production.

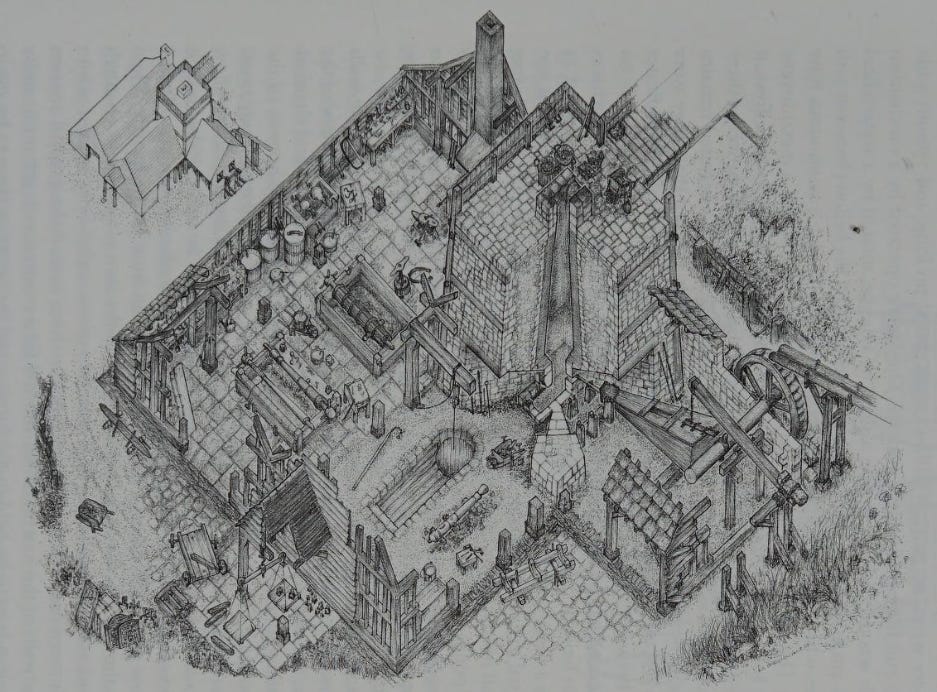

By the time the blast furnace arrived in England in the late 15th century, it had "developed into a stone tower, roughly square in plan and about 6-7 meters high". To give access to the top for adding the charge, blast furnaces would often be built near a hill or embankment, with a bridge connecting the hill to the top of the furnace. Air would be blown into the furnace by leather bellows driven by a water wheel. The furnace would run continuously for as long as there was available water power, or for as long as the hearth itself would last (as over time, the operation of the furnace would wear away the stone lining). Furnaces might last 40 to 60 weeks before needing to be rebuilt, during which time they could produce perhaps 4 to 5 tons of iron every 6 days.

The input requirements for 16th century blast furnaces were large. Though fuel consumption had fallen to roughly the level of the bloomery furnace (initially it used much more fuel than a bloomery), producing a ton of pig iron still required roughly 4.5-5 tons of charcoal, and 5.5-7 tons of iron ore. And as I’ve noted previously, the requirements to produce charcoal were enormous:

Producing a single kilogram of iron required perhaps 6 kilograms of iron ore, and 15 kilograms of charcoal. That charcoal, in turn, required perhaps 105 kilograms of wood. Turning a kilogram of iron into steel required another 20 kilograms of charcoal (140 kilograms of wood). Altogether, it took about 250 kilograms, or just over 17 cubic feet, of wood to produce enough charcoal for 1 kilogram of steel (assuming a specific gravity of 0.5 for the wood). By comparison, the current annual production of steel in the US is roughly 86 million metric tons per year. Producing that much steel with medieval methods would require about 1.4 trillion cubic feet of lumber for charcoal, nearly 100 times the US's annual lumber production.

And turning lumber into charcoal could only be done by way of an enormous amount of labor. A skilled woodcutter could cut perhaps a cord (128 cubic feet) of wood per day. A ton of steel would thus require ~130 days of labor for chopping the wood alone. Adding in the effort required to make the charcoal (which required arranging the wood in a specially-designed pile, covering it with clay, and supervising it while it smoldered), Devereaux suggests a one-man operation might require 8-10 days to produce ~250 kilograms of charcoal (which would in turn produce ~7.2 kilograms of steel), or roughly 1000 days of labor to produce enough charcoal for a ton of steel.

The blast furnace initially made producing iron much more complex. Whereas the iron from the bloomery could be used directly as wrought iron (a nearly-zero carbon iron mixed with slag), the high-carbon blast furnace iron had to go through a second, involved conversion in a finery furnace to get wrought iron. Schubert notes that the blast furnace spread despite being initially more expensive than making wrought iron in a bloomery:

The victorious march of the blast furnace was based on some striking advantages it had over the old [bloomery] process. The most conspicuous of these was the greatly increased output which was facilitated by the greater reduction of the ore owing to higher temperature and to remaining longer in the furnace. It was aided by the continuity of the smelting process extending at least over several weeks without interruption; in the bloomery smelting had to be interrupted each time the bloom...was taken out. Another factor...was the possibility of pouring the liquid iron from the furnace into molds intended, in particular, for bullets and guns. These were in great demand in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the course of which militias gradually were replaced by standing armies. Further, owing to the greater reduction, the ores were not confined any longer to pure ores as previously, but ores of inferior quality could also be charged.

— Early Refining of Pig Iron in England

Blast furnaces were a more complex and expensive method of producing iron than bloomeries, but they could produce iron in much greater amounts, could use ores that the bloomery process couldn’t, and produced a liquid, castable iron, more suitable for producing guns than wrought iron. A cast iron cannon was much cheaper than a bronze one.

The 18th Century: coke, steam, and the industrial revolution

By the early 1700s, Britain was producing about 20,000 tons of pig iron a year (about 3.6 kilograms per capita) from perhaps 50-100 blast furnaces.

Though its population had increased 25% between 1600 and 1700, iron production hadn’t increased at all. In part, this was due to the continuing reliance on charcoal as a furnace fuel, and the amount of wood required to produce it:

At the end of the 17th century, English blast furnaces were using about 40 kilograms of wood for each kilogram of pig iron. Obtaining sufficient wood to make charcoal was difficult — residents in areas around ironworks often objected to the ironworks consuming so much of the available wood, in some cases petitioning the king to intervene. And furnaces often had to shut down due to lack of available fuel…Beyond the volume of wood it required, charcoal had other limitations. It was brittle, limiting how high it could be piled in the furnace and thus how much iron could be smelted at once. And its brittleness also meant it couldn't be transported very far from where it was made.

The obvious replacement for charcoal in the blast furnace was coal, which, like wood, can be transformed via pyrolysis into a mass of nearly pure carbon called coke. The switch from charcoal to coke was first accomplished by Abraham Darby and his son Darby II in 1709 for the production of thin-walled cast-iron cookware, and over the next several decades the use of coke would spread to the rest of Britain:

Darby was successfully able to produce thin-walled pots with coke-smelted iron, but coke didn’t immediately displace charcoal as a blast furnace fuel. Coke-fired blast furnaces were not any cheaper to operate than charcoal-fired ones, and the use of coke resulted in sulfur impurities in the iron, which, while not a problem for castings, made the iron unsuitable for conversion to wrought iron. As of 1750 only 10% of the pig iron produced in Britain was from coke-fired furnaces.

But coke could be piled higher in a blast furnace without being crushed, enabling larger furnaces. As Darby's son (Darby II) built larger blast furnaces…the increased heat caused the excess sulfur to be removed, making the iron suitable for conversion to wrought. Coke-smelting took off in Britain in the 1750s, and by 1788 almost 80% of pig iron in Britain was produced in coke-fired furnaces.

The change to coke was especially important in Britain, where supplies of lumber for charcoaling were increasingly limited. In countries with abundant supplies of lumber, the change often took much longer. As of 1854, “nearly half the iron in the US and France was still produced using charcoal. Coke-fired blast furnaces didn’t appear in Italy until 1899.”

Beyond the switch to coke, the 18th century saw several other changes to blast furnace operation. Furnace linings, previously made of sandstone, had largely changed to brick, and would often be separated from the outer body of the hearth by a layer of sand. And while in the early 1700s air was still blown into the furnace using a water wheel connected to a leather bellows, the development of the Newcomen engine in the early 1700s enabled furnaces to switch to steam power. Early installations of steam engines often simply grafted these onto water wheel-powered furnaces: Darby II’s blast furnace used a Newcomen engine to pump water uphill, where it would flow back down over the water wheel. But by the late 1700s, furnaces were being blown directly by steam engines connected to large pistons to move the air. This change eliminated the need for blast furnaces to be near sources of moving water, allowing them to be located closer to sources of coal for coking.

Steam engines could blow more air than a water wheel-driven bellows could, which allowed a furnace to produce more iron, and coke could be piled higher than charcoal without being crushed, allowing the construction of taller, higher capacity furnaces. By the early 1800s British blast furnaces had reached 14 meters in height, and were producing roughly 1500 tons of iron per year on average. British iron production went from 20,000 tons in 1720 to over 250,000 tons in 1806 (roughly 20 kilograms per capita), nearly all of which was produced with coke. Over the course of the 18th century, Britain went from being a marginal producer of iron to the largest producer in the world.

The 19th Century: hot blast, hard driving

An early 1800s British blast furnace produced, on average, 4-5 tons of pig iron a day, around 5 times as much as a furnace built in the 1500s. But furnace fuel requirements hadn’t fallen at all; if anything, they had increased. Furnaces required on the order of 7-10 tons of coke for each ton of iron.

That changed with the development of the "hot blast," preheating the air before blowing it into the furnace. The hot blast was first developed by James Neilsen in the 1820s, and reduced the amount of fuel the blast furnace required by 40%-75%. Tylecote notes one furnace which in 1829 required 8 tons of fuel for each ton of iron produced, and which 4 years later needed less than 3 tons of fuel per ton of iron after the introduction of hot blast.

There were other benefits to using hot blast. It increased the temperature of the furnace, which (in some cases) allowed coal to be used instead of coke as a furnace fuel. In the US, Pennsylvania anthracite coal became a popular fuel for blast furnaces, and was primary fuel for US blast furnaces until the end of the 19th century. The increased blast temperature also made the reactions run faster (increasing furnace output), and allowed the use of lower-quality iron ores.

The hot blast was further improved by the use of a regenerative stove, first developed by Alfred Cowper in 1859, which adapted Siemens’ regenerative furnace (used, among other places, in the open hearth process). The regenerative stove captured the hot gasses which escaped from the top of the furnace, and used them to preheat the incoming air. Efficiency was increased further by burning the waste gas, generating additional heat. Not only did recycling the waste heat reduce fuel requirements, but it allowed the hot blast to get even hotter, which increased fuel efficiency further. By the end of the 19th century, thanks to the hot blast and further increases in furnace size (which also reduced fuel consumption), blast furnace fuel consumption had fallen to perhaps 2 tons of coke for each ton of iron in the US, and 1.4 tons per ton of iron in the UK.

Like previous improvements, these changes allowed blast furnaces to get even bigger, and increase their output even more. By 1880 blast furnaces had reached 22 meters in height, and by 1900 they were 30 meters (100 feet). In 1850 British blast furnace average production had reached over 5000 tons, and in 1860 Britain was producing more iron than the rest of the world combined.

But in the second half of the 19th century, American steel production began to take off. Average American blast furnace output went from 3500 tons per furnace in 1860 to 38,000 tons per furnace in 1900. By 1890 American iron production had surpassed Britain’s, and in 1900 America made 15,000,000 tons of pig iron per year (200 kilograms per capita), nearly 40 times the output of the entire world in 1800.

This output was achieved not necessarily by using more blast furnaces, but by increasing the volume of material flowing through them. By adding more, and more powerful, blowing engines to force more air into the furnace (known as “hard driving”), furnace output could be drastically increased. Carnegie Steel’s “Lucy” furnace produced 13,000 tons of pig iron per year when it was built in 1872 (already an exceptionally large furnace for its day). By the 1890s, its output had increased to 100,000 tons of iron per year.

The form of the blast furnace also changed during this period. As late as 1860, blast furnaces still closely resembled their 16th century counterparts — truncated stone pyramids built next to hillsides. But over the next 20 years, they would evolve into their modern form: cylindrical iron shells lined with brick, with hoists for raising material up to the top.

The 20th Century: mechanization, science, scale

By the turn of the 20th century, iron in the US was increasingly produced in large, integrated steelworks. Liquid pig iron would often be taken directly to a Bessemer converter or an open hearth furnace in the same facility, where it would be turned into steel, eliminating the molding and remelting steps of the previous process.

As furnace output continued to increase, keeping them fed with material posed a major problem. As Hogan notes, "a large furnace with a 30,000 cubic foot capacity was a hungry monster that had to be fed continuously 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year." Manual labor had traditionally loaded the furnace, but a large furnace might require 2000 tons of material added each day, which "could not possibly be handled by the vertical hoist and the hand-filling methods."

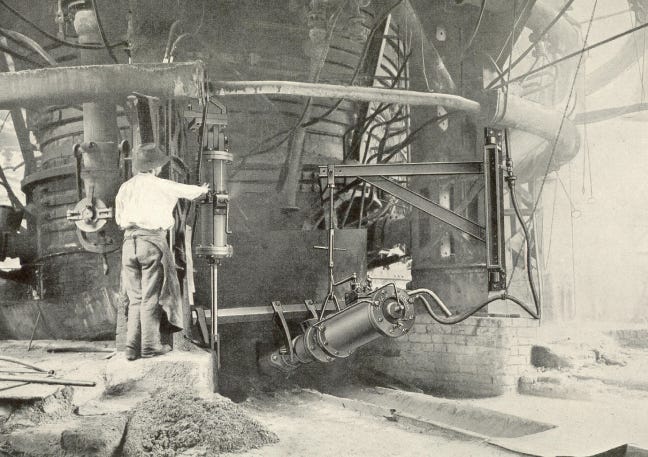

In the late 19th and early 20th century, these manual methods were increasingly replaced by machines. Mechanical "skip hoists" would automatically dump layers of ore, coke, and limestone into the top of the furnace, where they would be spread evenly by revolving “bells”. Tapping the furnace, which had previously required the labor of “8 to 10 men,” was now performed by mechanical rock drills which drilled a hole in the furnace, and clay guns which sealed the holes after tapping. By the 1920s, blast furnace operations were often fully mechanized, which allowed them to increase output without adding more labor. When a highly mechanized blast furnace was rebuilt in the 1920s to double its annual output, its labor costs per ton fell by 50%. As mechanization continued, labor hours per ton of iron produced fell from over 2 in 1920 to around 0.5 in 1940.

Blast furnace linings were also upgraded during this period. By the late 1800s, furnace lining lifespan was around 18-30 months, after which furnaces would need to be relined, a costly process that took several months. But better lining materials (such as vacuum-pressed bricks) and lining cooling systems gradually increased lining lifespan. By the early 1900s, lining lifespan had reached 4 years, and continued to improve. Today, with the use of carbon bricks as a refractory, furnace linings can last for 15 to 20 years before needing to be replaced. Japanese steelmakers have adapted the system of large-block construction used in shipbuilding to blast furnace construction, enabling lining replacement to occur much faster.

Furnace fuel requirements continued to fall. Removing the water from the air blast (known as “dry blast”) stopped heat being wasted in heating up the water, reducing fuel consumption. Further fuel savings came from even greater increases in blast temperature. In the mid-1800s, the hot blast was around 600 degrees Fahrenheit. By the 1970s, it was 1800-2000 degrees. Injecting oxygen directly into the furnace (known as “oxygen enrichment”) further increased both temperature and fuel efficiency. Ironmakers replaced some fraction of coke with other, cheaper fuels, such as oil or pulverized coal. By 1950, fuel rates in the most efficient furnaces had fallen to 0.9 tons of fuel for every ton of iron. By 1970, they had reached 0.5 tons.

Inputs to blast furnaces changed dramatically. During the early 20th century coke production changed from beehive ovens to byproduct ovens. Like the Cowper stove, byproduct ovens recycled waste gasses to reduce fuel requirements. And whereas beehive ovens were operated at coal mines, byproduct ovens were operated at the furnace. This allowed them to use blended coal from several sources, and resulted in a more uniform, better performing coke.

In the US, ore was increasingly mined from the incredibly prolific Mesabi Range, which had a much finer texture, and produced much more dust than previous ores. And both the US and Europe were increasingly reliant on lower-iron content ores as higher-iron content ores were exhausted, The result was ore beneficiation, where fine ore masses would be heated and bound together via sintering, or crushed and combined into pellets of higher ore percentage via pelletization. Small amounts of limestone could also be added during this process to create a “self fluxing sinter,” which reduced the amount of limestone that needed to be added to the furnace. The use of pellets and sintered ore also allowed further increases in blast temperature, as the finer ores required lower temperatures to carry out the reactions. To reduce the dust escaping from the top of the furnace (which often had significant iron content), dust catchers were added to furnaces.

Blast furnace operation transformed from an art to a science in the 20th century. In the 1870s, Carnegie Steel was an outlier in the industry for employing a chemist, and Carnegie noted that for many years afterwards his competitors claimed “they could not afford to employ a chemist.” By the 1920s, the specific chemical reactions taking place in different parts of the furnace had been mapped in great detail, and understanding the chemistry involved was considered fundamental to the process of ironmaking. Process control was also greatly improved during the 20th century, and in the second half of the 20th century blast furnace operation grew to be monitored via sensors and automatically adjusted via computer.

And above all, the scale of furnaces continued to increase. The development of “high top pressure blowing,” which increased the pressure in the furnace by restricting the flow of gas out the top, enabled even greater volumes of air to be blown in. Steelworks added bigger buckets for moving ore, bigger ladles for moving hot metal, bigger skip hoists, and special conveyors for moving enough coke into the furnace. By 1950 the average blast furnace in the US was producing 265,000 tons of iron a year, at which point the US was producing more than half the world’s steel. By 1973 average US furnace output had more than doubled to 648,000 tons a year. Japan, which built its iron industry from scratch after WWII and had few older, smaller furnaces, was producing an average of 1.47 million tons per furnace per year by 1973. The largest blast furnace in the US today can produce 3.6 million tons of pig iron per year, 10,000 times as much as a 16th century blast furnace, 14 times what all of the UK produced in 1806, and 170 times what the UK produced in 1720. A 1977 retrospective on the evolution of the blast furnace described scale as “the biggest single factor” in the improving economics of ironmaking.

The 21st Century: The end of the blast furnace?

But scale can’t increase forever. The production of blast furnace pig iron in the US peaked in 1969 at 95 million tons. By 2020, that had fallen to 18 million tons, less than the US made in 1905 (per capita, it’s less than we made in 1872). Starting in the 1960s, the blast furnace operations of large, integrated steelmakers were increasingly outcompeted by smaller electric arc-based minimills, which were significantly cheaper to build. In 1920, the largest US steelmaker was US Steel, a huge integrated steelmaker that was the first company to be worth more than a billion dollars. 100 years later, US Steel is still around, but the largest US steelmaker is now Nucor, which makes steel in electric-arc-equipped minimills. Even US Steel now operates several electric arc plants. A blast furnace hasn’t been built in the US since 1980.

Japan, which eclipsed the US as the world’s largest steelmaker at various points in the second half of the 20th century, continues to produce a majority of its steel in blast furnaces, but the number of operating Japanese furnaces has dropped by half since the 1970s, and its furnace size and fuel efficiency have both plateaued. As one researcher noted, hundreds of years’ worth of furnace engineering has resulted in a tightly optimized process that’s hard to keep improving.

Worldwide, larger furnaces continue to be built, but the rate of increase has slowed. The current largest blast furnace in the world only produces about 55% more iron than the largest furnace in 1980. By comparison, between 1937 and 1980 the largest blast furnaces in the US increased in output by roughly 500%.

Blast furnaces continue to be constructed around the world, particularly in China, which now produces more steel than the rest of the world combined. For the foreseeable future, recycling steel scrap won’t be sufficient to supply the world’s need for iron, and we’ll continue to need iron ore based methods of steelmaking. But blast furnaces, like cement plants, have the unfortunate distinction of producing CO2 as a fundamental part of the process: a blast furnace is essentially a machine that turns iron oxide and carbon into iron and carbon dioxide. Worldwide steel production is responsible for around 7-8% of carbon emissions, and producers are largely focused on finding a way to produce iron from ore that doesn’t emit CO2.

Most of these efforts are centered on the direct reduction route, which turns iron oxide into metallic iron without having to melt it. In the current direct reduction process, iron ore gets heated below its melting point in syngas, a mix of carbon monoxide and hydrogen derived from natural gas, which produces “briquettes” of reduced iron, along with carbon dioxide and water. The reduced iron is then melted in an electric arc furnace, where it gets turned into steel. Today, about 7% of the world’s iron is made via direct reduction to electric arc furnaces, most frequently in places like the Middle East, where natural gas is cheap and coke is expensive.

Direct reduction with carbon monoxide still produces carbon dioxide, but direct reduction with hydrogen only produces water as a byproduct. “Green steel” efforts are thus often centered around finding low-carbon ways to produce hydrogen to use in the direct reduction process. Of the 72 green steel projects listed on this “green steel tracker,” 49 of them involve low carbon hydrogen production, mostly either “green” hydrogen made via electrolysis or “blue” hydrogen made from natural gas plus carbon capture.

The transition from blast furnace iron to direct reduction was predicted as far back as the 1970s: even back then the economics appeared favorable. Perhaps climate concerns, and the resulting investment rush, will be the push it needs to ascend, ending the blast furnace’s reign.

Sources

Books (roughly in order of importance)

R.F. Tylecote, A History of Metallurgy

William Hogan, Economic History of Iron and Steel Industry in the United States

Vaclav Smil, Still the Iron Age

Peter Temin, Iron and Steel in Nineteenth-Century America: An Economic Inquiry

Carnegie Steel, The Making, Shaping and Treating of Steel (Also later editions by US Steel)

Alan Williams, The Knight and the Blast Furnace

Robert Rogers, and Economic History of the American Steel Industry

Dudley Jackson, Profitability, Mechanization and Economies of Scale

Jeremy Hodgkinson, The Wealden Iron Industry

Papers and other sources (roughly in order of importance)

Terrence Dancy, The Evolution of Ironmaking

Philip Riden, The Output of the British Iron Industry before 1870

Robert Allen, Collective Invention

Bo Carlsson, Economies of Scale and Technological Change: An International Comparison of Blast Furnace Technology

Fathi Habashi, A short history of electric furnaces in iron and steelmaking

Leonard Engel, Smelting Under Pressure

Masaaki Naito, Development of Ironmaking technology

Peter King, The Production and Consumption of Bar Iron in Early Modern England and Wales

Kaowaka et al, Latest Blast Furnace Relining Technology at Nippon Steel

Footnotes

[0] - Scrap steel will also often be added to the molten pig iron during the refining process.

[1] - Other complicating factors are that there are often multiple relevant performant axes and the successor technology often isn't superior on all of them. Crucible steel continued to be used for tools, for instance, after the Bessemer process was developed.

[2] - This is a high-level simplification, and there will be a series of interim and more complex reactions taking place in the furnace.

An additional resource, written for a (primarily) eBook series, which is therefore useful as a starting point: A Profile of the Steel Industry: Global Reinvention for a New Economy, by Peter Warrian (Author) Second Kindle Edition, 2016. Peter came from a steel family in Hamilton, ON. He was the research director for the United Steel Workers prior to getting a PhD and a degree from the MIT Sloan School, so his book covers a lot of labor and policy issues, and not just the economics. Mea culpa: Peter and I co-authored a 2017 book in the same series on the global auto industry. Peter is a Member of the Order of Canada (cf. "Sir" in the UK).

"The blast furnace has been described as "one of the half-dozen fundamental machines of industrial civilization."

Would love to know what the other 5 machines are.