The Rise and Fall of the Manufactured Home, Part II

When we left off, over a few short years mobile home manufacturing had grown into a massive industry, and was supplying an increasingly large fraction of the US’s housing. In 1973, 580,000 mobile homes were shipped, just over 50% of the number of single family home starts that year (1.1 million), and 22% of total housing units produced that year (including single family, multifamily, and mobile homes). The Department of Commerce predicted that mobile home shipments would be between 750,000 and 850,000 by 1980.

The HUD Code

As a result of the increasing size and importance of the mobile home industry, and growing concern about mobile home safety [0], in 1974 Congress passed the Mobile Home Safety Standards Act, which placed mobile home regulation under the purview of HUD. HUD then began the process of developing a set of safety standards for mobile homes.

The industry hoped that HUD would simply adopt the ANSI A119.1 standard, which by then had been in use for over a decade and had been adopted in some form by over 40 states. Of the 1000+ responses received by HUD regarding new standards, over 800 of them were requests that ANSI A119.1 be adopted.

HUD opted not to do this — the explanation given was that they were reluctant to effectively hand regulation authority over to a third party. The HUD Code was ultimately based on A119.1, but it was modified based on the results of several studies of mobile home performance (for instance, HUD analyzed the problems encountered on 4000 mobile homes that they had purchased as emergency housing for Hurricane Agnes relief, and the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) performed several studies on mobile home fire performance).

The HUD Code went into effect in 1976. HUD estimated that the new, stricter regulations added approximately $380 to the cost of a mobile home, while the average dealer estimate was closer to $500 (or about 4% of the cost of a typical singlewide at the time). Much of this increased cost seems to have been due to increased administrative requirements, rather than physical changes.

The stricter HUD code seems to have had its intended effects. The rate of fire death in mobile homes, for instance, had been 3 times higher than in conventional homes prior to the HUD code, a difference that was eliminated after the HUD provisions took effect:

Collapse and decline

1974 also saw the collapse of the US housing market, following the energy crisis-induced recession. Total housing starts (including mobile home shipments) fell by over 50%, from 2.9 million in 1972 to 1.3 million in 1975.

The mobile home industry was hit especially hard. While single family and multifamily housing starts declined by approximately 50%, mobile home shipments declined by 63% (from 580,000 in 1973 to 213,000 in 1975). 40% of mobile home manufacturers went out of business. And while the conventional housing industry bounced back (to some extent — 1972 would ultimately be the peak of conventional housing construction as well as mobile home construction), the mobile home industry never quite did. Conventional single family and multifamily starts had recovered to 85% of their previous high by 1979, but mobile home shipments were only 45% of their previous high. Rather than exceeding 800,000 units per year as predicted, mobile home shipments have never since exceeded 400,000 units per year and, outside a six-year window in the early 1990s, have never passed 300,000 units per year. In 2021 manufactured home shipments (they officially changed from “mobile homes” to “manufactured homes” in 1980) were just 106,000 units, approximately 6% of total housing units built that year.

Why didn’t the mobile home industry bounce back? What stopped it from continuing to take a larger share of the housing market in a Clay Christensen-style low end disruption? Why aren’t we all living in mobile homes?

The HUD Code theory of industry decline

Blame for the industry’s troubles often centers on the HUD Code, which was stricter in both requirements and enforcement than previous mobile home regulations. Arthur Bernhardt gestures towards this in “Building Tomorrow,” a long-term study of the mobile home industry published in 1980:

The dramatic shakeout of the 1973-1975 recession resulted in an industry where the “surviving” firms are financially sophisticated. Increasing government intervention has forced these “survivors” to develop new staff and expertise in dealing with the new regulatory red tape.

…The irony seems to be that consumerism and government have raised entry barriers to the point that new competition is discouraged from entry and production costs are significantly higher.

And Allan Wallis makes similar claims in “Wheel Estate,” a history of the mobile home industry published in 1991:

In previous recessions, small manufacturers would go out of business and larger manufacturers would close some of their branch plants until the economy turned around. Coming out of this recession, however, small manufacturers were faced with a new set of regulations and a complicated design approval and inspection system. Instead of spot-checking units, every unit being manufactured now had to be inspected in the plant. For a small firm turning out just a few units a week, the cost of filing drawings for approval and paying an inspector to come for a factory visit might mean the difference between being competitive or out of the market.

He also states that “whether the benefits of institutionalization will outweigh its costs is yet to be determined.”

But the strongest proponent of this theory is James Schmitz. In his paper “Solving the Housing Crisis Will Require Fighting Monopolies in Construction,” Schmitz claims that the failure of mobile homes to displace site-built construction was the result of sabotage by HUD and NAHB (organizations that he confusingly calls “monopolies”), on behalf of conventional builders, of which the HUD Code was one particular instance of:

the key monopolies involved in blocking small modular homes are the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). They have successfully squashed the emergence of these factory houses.

…In particular, HUD was able to introduce a national building code (Nat-BC) for factory-built homes, in particular, manufactured homes. This Nat-BC was sold as a benefit to the manufactured housing industry, though it was a mechanism to destroy it.

…The first reason the Nat-BC was devastating, then, is because in the areas where producers of manufactured homes actually competed with stick builders, typically small towns and rural areas, there were often no local building codes, or not severe ones. With the Nat-BC, factory builders had to meet a strict code; stick builders faced no code. This feature of the regulations by itself meant great sabotage.

The added burden of the HUD Code, according to Schmitz, made mobile homes less competitive compared to site-built homes, particularly in what had previously been their most important areas — places with little to no building code enforcement.

Schmitz places particular blame on the HUD requirement that mobile homes, even ones that will be permanently attached to a foundation, have a steel chassis that allows them to (theoretically) be moved. Not only does the chassis add cost, but it provides a mechanism for jurisdictions to discriminate against mobile homes:

Another feature of the code is the requirement that the homes have a permanent chassis. Before this requirement, these homes would be transported to their site on a chassis, as this is the most cost effective means of transport. The chassis would then be removed, and most would be put on a foundation.

…The permanent chassis requirement has a significant negative impact on the industry. First, by requiring a chassis, the regulation endeavors to make the small modular home resemble a trailer, linking the prejudices of trailers with small-modular homes. Second, since the house has a chassis, local zoning laws can often be applied to block it from the local area. Third, since it has a chassis, it’s argued that it can be moved (though they aren’t moved), so that the houses are financed as cars (with personal loans) and not real estate. Fourth, the regulation increases the cost of manufacturing the house.

And indeed, manufactured home manufacturers have argued (unsuccessfully) that the chassis requirement needlessly adds cost to mobile homes and should be removed:

I can assure you that when a homebuyer buys a home from me and wants to finance it for 30 years and have it installed on a permanent foundation, the homebuyer prefers to have the chassis removed. In many cases homebuyers prefer to have their manufactured homes placed over basements. Because of the presence of a chassis, we must dig the basements deeper and erect more costly and unsightly piers. I could save my homebuyer significant costs, both in factory costs and installation costs, if I could order a home designed to have the chassis removed.

(It’s worth noting that it’s somewhat disingenuous to use a 30-year mortgage example here, as the majority of manufactured homes are financed with shorter, personal property loans.)

Problems with the HUD Code theory of industry decline

The problem with the HUD Code theory of industry decline is that it doesn’t fit the evidence especially well.

For one, the HUD code didn’t regulate what was previously unregulated — nearly all states required mobile homes to meet their own local code requirements, largely based on A119.1 (the same standard that the HUD code was ultimately based on). Manufacturers had in fact advocated for a uniform nationwide mobile home code (though not necessarily a federal code, they weren’t necessarily thrilled with HUD oversight) to specifically prevent the problems that were occurring with multiple jurisdictional requirements. From “Building Tomorrow”:

…Although the codes were based on ANSI A119.1, they were not all the same. Some states adopted the ANSI code in whole, others, in part, and still others, with modifications and amendments.

These state by state variations prevented full interstate reciprocity and uniformity…multiple inspections of the same unit in-state, out-of-state, and on-site raised costs and damaged interstate marketing…individual inspectors interpreted and enforced the same code with different levels of strictness…Differing state requirements forced manufacturers to produce the same model under various structural and mechanical standards or else overdesign to the toughest specifications. Either alternative increased the cost of mobile homes. State-by-state approval of new materials and processes also raised costs and discouraged innovation.

It’s also hard to find evidence that the HUD Code caused any substantial cost increase. Dealers’ own estimates were that the HUD provisions only added on average about 4% to the cost per square foot for a typical singlewide (and this ignores any potential savings from the reduced insurance cost due to improved fire safety, or from reduced energy consumption).

If we look at average mobile home cost per square foot over time, it does rise, but a) it was rising prior to the introduction of the HUD code and b) it rose less than the cost of new site-built construction (and after 1978, rose less than inflation). As a fraction of the cost of conventional construction, mobile homes got cheaper following the HUD Code, not more expensive:

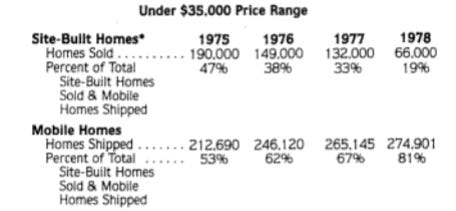

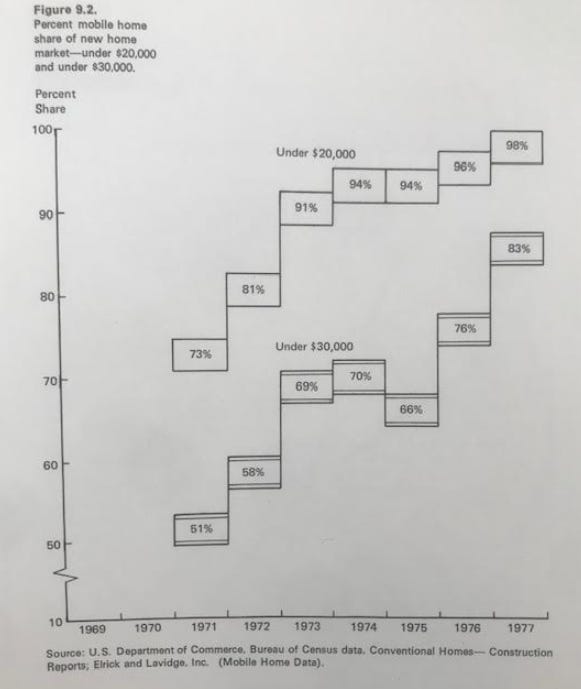

And mobile homes continued to take an increasing share of the low-end home market:

Regarding the chassis requirement as a mechanism to discriminate against mobile homes, this also doesn’t fit the data. As we’ve seen, mobile homes were subject to restrictive zoning practices long before the HUD Code (and its chassis requirement) was enacted:

In the early 1970s, 60% of communities excluded mobile homes from being sited on private lots, and a survey by the American Planners Association found that residents in 80% of communities wanted to exclude mobile homes. Metro areas often tried to prevent the construction of new mobile home parks, with cities such as Des Moine and Miami putting a moratorium on new park construction. The state of Illinois approved just 1 mobile home park between 1955 and 1975. Outside of parks, mobile homes were largely relegated to areas outside of cities where there were fewer zoning restrictions (75% of rural counties allowed mobile home placement on private lots, compared to just 31% within cities and 20% within suburbs). Where mobile homes were allowed, they were often restricted from being located in residential areas — 15% of communities only allowed mobile homes in areas zoned for commercial or industrial.

In fact, the passage of the HUD Code was followed by a significant decrease in restrictive zoning practices against mobile homes. Via Regulating Manufactured Housing:

In 1970, only 38% of communities surveyed by the American Planning Association permitted mobile homes on individual lots outside of parks. By 1985 that had risen to 60%.

In 1970, less than 1% of surveyed communities permitted mobile homes “by right” in residential districts (“by right” is when development can proceed without special review). By 1985, that had risen to 52%.

By 1989, 22 states had passed mobile home antidiscrimination laws. Today, over half of states require localities to allow manufactured homes somewhere in their jurisdiction.

There also doesn’t seem to be much of a dropoff in the creation of new mobile home parks. The number of mobile home parks increased from 24,000 in the early 1970s to over 50,000 by the late 1990s [1].

At least some sources credit this relaxation of zoning stringency to the increased quality and safety that resulted from the HUD code:

The more durable and safer manufactured home built in compliance with the HUD code is enjoying greater public acceptance and has prompted local officials to relax certain restrictions on manufactured housing.

And at least some favorable zoning court rulings for mobile homes were the result of the HUD Code having comparable stringency to local building codes.

Regarding cost, the steel chassis adds approximately 12% to the cost of a manufactured home, per “Building Tomorrow” — a significant burden for sure, but not an overwhelmingly large one (and, empirically, one that hasn’t impacted how much cheaper manufactured homes are than conventional homes).

(Schmitz’ paper also has several other incorrect claims [2].)

Better explanations

Can we find a better explanation for the industry’s decline? One that doesn’t work via the mechanisms of manufactured homes getting more expensive compared to site-built, or zoning getting more restrictive (since neither of those seems to have occurred)?

One possible explanation is that mobile home manufacturers were more severely affected by the housing downturn because it was harder for them to scale down their operations due to high fixed plant costs. When the housing market turned, producers went out of business and production capacity was removed, making it hard for the industry to bounce back — recovery comes slowly, if at all.

This sort of vulnerability is mentioned as a factor in “Building Tomorrow:”

Unlike the labor intensive traditional housing system, the capital intensive mobile home production system is more vulnerable to changes in demand. A sudden demand drop can drastically reduce the capacity utilization rate; correspondingly, the fixed cost per unit of output increases…When even minimal profits were eliminated in the recession, many mobile home producers filed for bankruptcy. The traditional on-site builder, on the other hand, not having to absorb the fixed costs of maintaining a factory…can adapt to sudden demand drops more easily than a mobile home manufacturer.

If capital overhead-induced failures were responsible for prolonged capacity reduction, we would expect to see something similar happen with “normal” prefabricated building (factory-built housing that meets local building code requirements, rather than the HUD Code). We see a similar sort of decline in 2008, where prefabricated housing units drop and then never recover:

However, it doesn’t seem as if this happened in the 1970s. By 1970 prefabricated housing units had reached over 250,000 per year:

This did drop in 1974, but unlike mobile homes, quickly recovered. By 1976 prefab builders (which doesn’t include mobile homes) were shipping over 250,000 housing units a year:

So the 1973 decline didn’t seem to result in a prolonged capacity reduction for “normal” prefab. Prefabricated construction did ultimately decline (by 1992 it was down to just 60,000 single family housing units a year), but not until the 1980s.

Another possible explanation is the mobile home industry was uniquely impacted by their typical customer: lower-income buyers buying lower-cost homes. This factor is also mentioned in “"Building Tomorrow:”

In 1974, the effect of recessionary conditions of tight money and increased unemployment had a severe impact on the mobile home industry. Blue-collar workers, the major occupants of mobile homes, were most affected by the high rate of unemployment and many did not have the income to purchase or to maintain loan payments on homes.

Once piece of evidence is that the decline in sales largely came from the smallest, cheapest units — larger homes were less affected:

We also see that total sales volume increased faster than units shipped, indicating a shift towards larger, more expensive models:

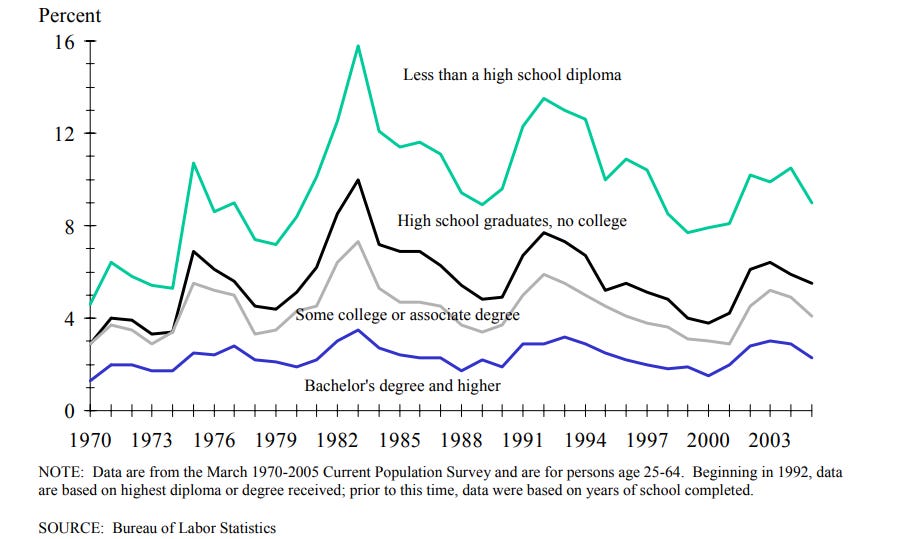

And we also see that unemployment rate is generally substantially higher for lower income brackets:

However, at other times manufactured home demand seems to be countercyclical, with manufactured homes, being more affordable, becoming more popular during a downturn. In the early 1980s recession, for instance, manufactured homes shipments declined much less than site-built housing starts, and manufactured homes as a % of total housing units went from under 12% in 1977 to over 18% in 1982.

The lax lending theory of industry decline

But there’s other ways that sales to low-income buyers might have been the culprit. One possible way is that the huge run-up mobile home sales in the early 1970s was driven by lax lending standards. When the downturn came, this created a brutal industry dynamic — demand for new housing drops, lending standards tighten (narrowing the potential market), lenders exit (lowering competition) and repossessed units flood the market.

This seems to have occurred in the 1973 recession. Here’s one lender’s congressional testimony:

Our experience in mobile home lending has been very similar to that of other savings and loan associations. In the early 1970s, fostered to a great extent by our own greed, we invested heavily in mobile home loans…Because of the apparent high rate of return on these loans, competition for them from various lenders was stiff…and in some cases it was necessary to neglect some of the basic underwriting principles. Almost all of the loans were bonded or insured, but the fine print in the bonds and the lack of ultimate financial responsibility of many of the bonding companies made the bonds almost worthless. Most of the service companies…vanished into the woodwork. The result was that in 1974 we became to experience an increasing number of mobile home repossessions.

In the first half of 1975, mobile home repossessions were averaging 10,000-20,000 per month (the annual equivalent of ~180,000 per year, or close to half the number of new shipments for that year).

This dynamic is specifically blamed for the industry’s downturn in a report to the Federal Trade Commission:

A major reason for the recession in the mobile home industry was the tightening of credit policies by lending institutions. During the period of rapid growth in the early 1970s, many people who were poor financial risks obtained mobile home installment loans and thousands of repossessions resulted. As a result, lenders were more cautious in extending credit to new mobile home purchasers and older repossessed units flooded the market.

(Interestingly, this report specifically discounts the introduction of the HUD Code as a cause for industry decline.)

Another strong piece of evidence for the lax lending theory is that the same dynamic, with the same result, reoccurred 20 years later. During the mid 1990s, manufactured home sales were booming, and actually approached their previous high in terms of fraction of total housing shipments [3].

But this boom was also driven by a relaxation of lending standards, with predictable results:

Comparatively few lenders specialize in home loans for manufactured homes. Still, their numbers more than doubled (from 11 to 24) between 1993 and 1998, according to government figures. Subprime loans were also a popular financing option for manufactured homes, and such lenders grew sixfold from 1993 to 1998, to more than 250 firms.

As competition for loans rose, loan standards were relaxed. Average length of loans increased, and 30-year loans—unheard of in earlier days—became more common. Down-payment requirements were lowered, and lenders started buying down interest rates with points.

…In short, the lending sector wasn't pricing loans appropriately for the underlying risk. By 1999, delinquencies and repossessions began to creep up, though by how much is tough to say. "We do know [repossessions] were extremely high," Stinebert said. But no hard figures are available because lenders had no uniformity regarding the definition of repossession, in part because many "were trying to hide" the fact that their portfolios were loaded with bad-performing loans for manufactured housing, he said.

Estimates from several industry sources put annual repossession at between 80,000 and 100,000 for several years during this decline. A 2005 report by Lehman Brothers said repossessed inventory went from $300 million in January 1999 to $1.3 billion by the end of 2002, with recovery rates (the percentage of loan value recovered by sale of repossessed collateral) dropping "as low as 25 percent during the period."

…The pain has been spread through dealers, lenders and manufacturers. The number of active plants nationwide dropped from 330 in 1998 to just 210 last year. Production of manufactured homes in Wisconsin grew 40 percent from 1990 to 1995 to about 4,500 units and then steadily hemorrhaged to just 1,100 units last year, well below preboom levels, according to MHI data.

Lenders played a game of follow-the-leader into and out of the manufactured home industry. Fitch Ratings reported that as of January 2003, "an overwhelming majority" of lenders that had entered during the boom were no longer in the business.

An article in Manufactured Home Merchandiser (a trade publication with a series of increasingly bleak covers starting in the early 2000s) stated in 2003 that “For the immediate future, zoning, financing limitations, and a glut of repossessions will flatten sales.”

The early 2000s downturn would have been especially brutal, as it was followed by the larger housing market and financial collapse of 2008.

So, my current working theory is that manufactured home industry recessions have largely been driven by the relaxation, then contraction, of lending standards.

[0] - The statement of purpose in the act is to “reduce the number of personal injuries and deaths and the amount of insurance costs and property damage resulting from mobile home accidents and to improve the quality and durability of mobile homes.”

[1] - Also, it seems as if in practice the requirements for a steel chassis weren’t clarified until 1986, far after the annual sales had declined. Via “Wheel Estate”

In August 1986, HUD issued a letter instructing its agencies charged with design review to prohibit manufactured homes in which an all-wood floor frame was substituted fro the typical metal frame chassis. By rejecting the wood frame, the Department was rejecting the idea of a removable chassis. In fact, the practice of building units with removable chassis had been going on for years, but a HUD sanction had never been requested.

Wallis goes on to claim that removal of this chassis “would have obliterated the technical distinction between manufactured and modular housing,” but I think this is incorrect. It’s perfectly possible for jurisdictions to treat manufactured and non-manufactured homes differently even if there’s no difference other than what’s tracked on the paperwork, the same way that governments treat citizens and non-citizens differently.

[2] - In particular, Schmitz spends a great deal of time claiming that one avenue of sabotage was for HUD to call mobile homes “manufactured homes” instead of modular homes, to ensure they could be discriminated against:

In 1976, HUD introduced another name for these small-modular homes, namely, manufactured home. But this only applies to small-modular homes produced after 1976. Those built before 1976 are now officially called mobile homes by HUD. So, these small-modular homes are called trailers, mobile homes and manufactured homes. Nowhere will you see them called what they are: modular homes. Monopolies, like HUD and NAHB, reserve the term “modular home” for large-modular homes. This is no accident. To describe small-modular homes as “modular” would lend them credibility. In this essay we’ll sometimes call them manufactured homes, though we realize this usage must change, that monopoly language that confuses must be fought against.

Putting aside for the moment the dubiousness of the idea that “manufactured” has obvious negative connotations while “modular” doesn’t, this wrong in numerous ways:

The change from mobile homes to manufactured homes was officially made in 1980, not 1976.

The change was the result of lobbying by the mobile home industry, not dictated by HUD.

“Manufactured home” was deliberately chosen because it would be associated with other forms of factory-built construction. At the time “manufactured home” was a catchall term for all factory-built housing. In the US Industrial Outlook, for instance, both mobile homes and prefabricated construction were categorized under “Manufactured Housing.” And in Bernhardt’s late 60s report “manufactured homes” are used to refer to factory-built homes other than mobile homes (this data, in turn, was supplied by the National Association of Home Manufacturers, who represented prefab builders).

This use of “manufactured home” continued into the 1980s. For instance, here’s a definition given in the report “Manufactured Homes: Making Sense of a Housing Opportunity”:

Manufactured housing is a generic term describing housing produced in a factory rather than at the actual site.

…There are two types of manufactured housing. The first type is built to state-adopted building codes that, in turn, are based on national or regional model codes, such as the Uniform Building Code (UBC). Included in this first type are precut or shell homes, components, panelized homes, modular or sectional homes, and so on.

…The second type of manufactured housing is built to a single national standard embodied in the federal Manufactured Home Construction ans Safety Standards…known as the HUD Code.

[3] - In fact, we see total occupied manufactured homes peak in 2001 - since then they’ve been on the decline:

I share your current working theory in part. The chattel collapse of 2000 remains partly responsible for tepid MH unit sales. Following 2000, the sub-prime run-up to 2008 drew many traditional MH buyers into unsustainable (it turned out) single family homes. Then the crash, credit tightening and resulting regulatory response to 2008 impacted MH chattel lending and home sales. But, what explains the last 5 - 7 years as housing demand really heated up?

From here, I go to zoning and planning approvals first. The number of MH communities being built roughly equals the number being closed down. Second, as someone who talks with a lot of would-be buyers, the MH community industry has a water cooler problem - i.e. what people say when you announce, "we are looking at a mobile home."

Dave Ramsey calls MH a depreciable asset and asks "why would you do that?" MH community closures put people out on the street - e.g. in Indiana with just 60 days notice - and subject people to what the Washington Post wrote were "massive rent increases." It all contributes to reluctant consumers and that narrows demand.

My view: The industry is in need of structural change. Long-term leases and access to residential mortgage loans (i.e. home only mortgages on leasehold land) would be one why to say and mean that these are permanent homes and worthy of residential mortgage loans. Think about MHCs as "true lease" communities and present that paradigm to town planners and the buying public. Our work is in helping homeowners form co-ops to buy their communities. That's the surest way to ensure that homeowners have long-term security and affordability. www.ROCUSA.org

I’m a little dubious about that 50,000 MH community number. I suspect the figure comes from a Homeland Security database of communities, which includes a lot of parks that no longer exist and many are under 25 pads.

The financing is a huge component of stagnant production numbers, and the personal property vs real property makes capital for the financing more expensive. The public policy around MH, making them difficult to qualify for rent support, exclusionary zoning, lower tax revenue (because of the personal v real property issue) conspire to make them a less attractive housing option for public support. Finally, outside of retirement communities, they’re invisible to most people and therefore no one recognizes the affordable component of these communities.

There’s also the issue of capital for park owners and Fannie/Freddie debt availability, but that’s a much longer comment.