What Construction Innovation Uptake Looks Like

We talk a lot around here about construction productivity, and how resistant it is to improvement. We’ve also talked about construction innovation, and the structural reasons that make it hard to introduce new products or technologies into the building process. These issues seem linked - it’s hard to improve productivity if you can’t introduce better methods, materials, or processes. So one way of thinking about construction productivity is that it’s an innovation problem, and solving it means making it easier for innovations to be adopted.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. But a good place to start is to look at some construction innovations, and see what their adoption process looked like - it’s hard to know how to make it easier to adopt innovations if we don’t know how they’re adopted now. After all, hard doesn’t mean impossible - despite its reputation, construction does innovate. If you’re in a building built in the last several years, chances are the room you're in has several technologies (such as low e-coatings on windows, PEX piping, or LED can lights) that were unavailable a few decades ago. So let’s take a deeper look at some construction innovations, and see what their uptake looked like.

The innovations

Our main source of data will be the Home Innovation Lab’s Builder Surveys. Since 1995, Home Innovation Labs have performed an annual survey of homebuilders asking them what materials, products, and technologies are being used in new homes. This will let us see how the frequency of different products and technologies has changed over time. We’ll supplement this with a few research publications that have tracked progress of various construction innovations or technologies.

The innovations I’ve chosen are below.

The bulk of these were chosen from a list of innovations that were examined in “The Diffusion of Innovation in the Residential Building Industry”, which looked at Home Innovation Labs survey data for 12 construction innovations between 1995 and 2001. Supplementing this with more up to date Builders Survey data gave me about 25 years worth of innovation uptake data to look at. The others (PEX piping and BIM in UK design firms) were pulled from these publications.

It’s a short list, but it still manages to cover a fairly broad range of the construction process. These innovations are installed by different disciplines, are used in different areas of the home, and are used at different stages of the construction process. They have different levels of disruption to the existing process (some can be dropped in with little change to the existing process, while some require a total rethinking of it), and they have different benefits (some primarily benefit the builder, others benefit the buyer).

Innovation diffusion modeling

Once we have our innovation uptake data, we’ll want to fit a model to it to better understand the structure of the process.

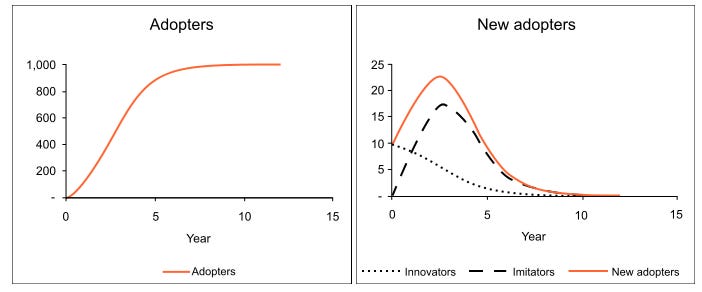

New product or technology adoption generally follows an S-curve - it spreads slowly at first, then picks up speed, and eventually tapers off. There are several possible models for this sort of adoption process.

One popular one is the Bass Diffusion Model, which is often used by marketers to predict new product uptake. Roughly, the Bass model assumes product adopters fall into two camps. One group, called innovators or independents, adopt the new product at some fixed rate - say 5% per time period. The other other group, imitators, have an adoption rate that’s a function of how many other people have adopted the product - the higher the number of existing adopters, the faster the imitators adopt. This gives the classic s-curve shape - initially product adoption is entirely by the independents. As more people start to use the product, the more the imitators join in, eventually tapering off as the market gets saturated.

The nice thing about the Bass model is that the parameters tell us something about the structure of the market - fitting the model means adjusting the rate of innovator and imitator uptake (p and q, respectively).

But there are many other possible models that can give us this S-curve shape. We can also use a simple logistic, or sigmoid model, of the following form:

Where x(t) is the number of new adopters in a time period, t is the time period and L is the maximum uptake attained.

For the innovations below I’ve modeled their diffusion using both a Bass model and a sigmoid model. As we’ll see, this didn’t make an enormous amount of difference, and we get similar results from both.

Construction innovation diffusion

The innovation uptake data is below. For most of the innovations shown, it shows % of new homes that include the innovation over time (the exception is BIM use in the UK, which is % of firms using over time).

(click to embiggen)

We see a few different trends. For one, the uptake data seems to follow the S-curve pattern reasonably well (though with different curve shapes for each one). For another, we see that innovations have different amounts of market penetration - some top out at some fraction of the market, some reach complete saturation, some go nowhere. Fiber cement siding seems to top out at around 25-28% of new homes (though Hardieboard seems to be shooting for 35% of the market), vinyl windows get near 70%, and high efficiency AC has near 99%.

For the innovations that get the highest uptake, we see two mechanisms at work to make this possible - legislation and network effects. High efficiency AC adoption was aided by legislation - SEER 13 became the minimum standard air conditioner efficiency in the US in 2006. BIM adoption, on the other hand, is aided by network effects - construction documents produced by a particular piece of design software tend to require that design software for everyone who wants to interact with them. If you’re an engineer and the architect is using Revit, you need to use Revit as well.

One thing these S-curves don’t show is a long “flat” portion of the curve that occurs between when a technology was first invented, and when it starts to see commercial success. Most fiber-cement siding today is Hardieboard, which was invented in the mid 80s in Australia and introduced into the US in the early 90s, but fiber cement was first invented in the late 1800s. Modern wood/plastic composite decking was introduced in the 1990s, but the original material was developed in the 1960s. PEX took off fairly quickly in the early 2000s, but PEX was invented in the late 60s, and has been used for in-floor heating since the 70s.

This long ramp-up period likely kills many, many innovations, as there’s few organizations that are willing and able to make the investments required to develop a new construction product or technology. This is something we saw with the bricklaying robots - both SAM and HadrianX took many years of private investment before getting close to a marketable product, and it seems like both very nearly didn’t make it. Even if an innovation does succeed in some portion of the market, the creator may not have the resources required to scale it up. The structure of the market (many small builders, few with a large share of the market) means that it’s the building product suppliers that are most able to develop new construction innovations, as they’re the ones with the resources to do it. This likely limits innovations to what can be sold to existing builders.

Even without considering this long ramp up period, innovations take a long time to spread - even the “fast” innovations in our list take around 15-20 years or so to reach maximum uptake, and the slow ones (such as vinyl windows) take 40+ years.

And that’s if they manage to get traction at all - some innovations, like SIPs, have limped along with a tiny fraction of the market for many years, and this shows no signs of improving. The benefit is too low (and can be achieved in other ways), and disruption to the traditional process too large, for them to be a compelling offering to more than a small fraction of builders.

SIPs are in some ways unusual in that the technology has managed to survive at all. This may be due to the relative simplicity of the technology (from what I understand spinning up a SIPs production facility is relatively easy). Most innovations don’t have this luxury.

One interesting trend we see is what happens with innovation adoption during a tough business climate. We see a dip in market uptake for many of these innovations around 2007, right when the construction market was cratering during the financial crisis. It’s not obvious to me what the cause is here (builders getting more risk averse in a tough business climate, possibly).

Model parameters

Regarding the bass model parameters, we see some confirmation of construction as a “conservative” industry - the percentage adoption “p” for innovators is very low, much less than 1% in most cases. The percentage adoption for imitators, “q”, on the other hand, is quite high, ranging from 10-50%. It seems as though few people are willing to take a chance on a new innovation without seeing it tested. On the other hand, if your innovation is genuinely useful it can overcome this - PEX piping went from 15% of new homes to nearly 70% of new homes in just 10 years.

(Note that the value of these parameters is somewhat sensitive to what you choose as your “starting time” which can be tricky. I’ve done my best to ballpark the starting time for the products, using “when it became available for purchase” rather than when the technology was first developed, but doing this isn’t straightforward).

How does this uptake rate compare?

20 years seems like a long time - over that same time period we’ve seen two generations of phone technology go from zero to ubiquitous. Tik Tok went from 0 to a billion users in just five years. But outside of information technology, 20 years isn’t that long for an innovation to spread.

Consider cars. Hula et al looked at the time it took various automobile innovations to reach market saturation after they were introduced:

And Zoepf et al looked at a few more:

We see roughly similar diffusion times as we do in construction - some as fast as 10 years (keyless entry), but generally 20-30 years between first use and reaching maximum production share.

This is especially interesting considering the wildly different industry structure. Construction consists of a large number of small builders, each of which must be convinced to use your product. Cars, on the other hand, are produced by a small number of large manufacturers - naively, I would have expected that once a technology was “in the door” at one of them, uptake could proceed quickly. But it seems like large industries producing physical goods can only propagate change so quickly, regardless of the industry structure (it does take 5+ years to develop a new model of car, after all).

In cars we also see a long lead-up period before the innovation is deployed. Fuel injection was first invented in the 1800s, but didn’t see use in cars until the 1950s (and wouldn’t reach full uptake until the 1990s). Anti-lock brakes were first invented in the 1920s for use on aircraft, but weren’t used on cars until the 1970s.

We also see something similar if we look at agriculture. Consider this graph of farm equipment adoption from Chen 2019:

We see the same 20-40 year adoption time. Bedow 2013 noted something similar for corn technology adoption:

What makes construction different?

Overall these adoption curves don’t look all that different than in homebuilding. So why does construction feel so much less innovative?

Part of the reason is that innovations in other industries are often fundamentally new things, which offer functionality that didn’t exist before. A tractor isn’t just a better way of pulling farm equipment, it lets you do things that weren’t possible previously. Keyless entry gives a car the ability to do something that it couldn’t do before.

Construction innovations, on the other hand, tend to be improved versions of existing features. A vinyl window is better on some margin than a metal framed window, but it’s doing the same job that previous windows did. PEX piping is a genuine innovation (easier to install than copper, cheaper, and durable as long as you keep it out of direct sunlight), but it’s still doing the same job as copper pipe, and once construction is complete it’s hard to tell the difference.

To some degree this is a function of the fact that functionality tends to get pulled out of buildings over time (leaving a smaller “innovation attack surface”), but it’s not a necessity. Something like smart glass is an example of an innovation that would add substantial functionality to a building that also has approximately 0% market penetration (based on the numbers in this article, there are less than 1000 buildings worldwide that have smartglass installed).

There’s obviously a risk of selection bias here in how I selected which innovations to look at. On the other hand, it’s very hard to think of something a modern home does that a home in 1980 wouldn’t do. Looking at this list that Elizabeth Slaughter compiled of 100+ different home innovations that have been developed since the 1940s, only a small fraction of them are changes in functionality.

Because innovations are often marginal improvements to existing functionality, it allows the old way of doing things to stick around for a long time - builders may (rationally!) conclude that they already have the tools and expertise to use the existing systems, and it’s not worth it to invest in learning a new system. And a pure cost/efficiency improvement may eventually bump up against other, competing concerns like durability, familiarity etc. New functionality, on the other hand, eventually becomes a baseline expectation. On the Model T things like electric starters were add-ons that the buyer could purchase separately, but these eventually became standard equipment.

The innovations also tend to be things that can be dropped into an existing construction process without much disruption. The more changes it requires to the way a building gets built, the harder it will be for it to succeed. SIPs, which change both material procurement (since you have to design the panels ahead of time and order them from a specific manufacturer), AND how the building goes together (since you can’t, among other things, run services through the wall in the same way), really have it tough here. BIM is the big exception to this trend, since BIM a) requires a substantial disruption to the existing process, and b) requires significant upfront investment, but has nonetheless been extremely successful anyway.

Conclusion

So, so sum up.

Despite the difficulties at play, innovation in construction does occur. It’s slower than in information technology, but seems to spread at similar speeds as other industries such as cars and agriculture. However, there is often a long ramp-up period prior to an innovation beginning to be adopted, which likely screens off many new innovations. Successful innovations tend to be refinements of existing features or systems rather than new capabilities.

These posts will always remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work and also gain access to a members-only slack channel.

Construction Physics is produced in partnership with the Institute for Progress, a Washington, DC-based think tank. You can learn more about their work by visiting their website.

You can also contact me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or by email: briancpotter@gmail.com

Thanks for this post Brian. You touch briefly on the common problem with the construction innovations in your list--that they're lateral improvements on products, and have practically no impact on construction productivity. A fiberglass door takes as long to hang as wood door. In the case of vinyl windows, and by extension all modern clad-composite windows, proper installation actually requires an increase in labor inputs. PEX is a little faster to install than copper, but any productivity gain gets more than canceled when homebuyers demand more plumbing fixtures.

In theory, SIPS offer the most productivity gains on overall shell construction, but they create an additional planning burden on design and site management. They also can slow down some of the trades because of the challenges associated with running wiring and plumbing.

In my brief career in single family home architecture the highest impact innovation has probably been LED lighting. Even in that area, easier and faster installation hasn't moved the needle on construction costs or speed.

There is quite an extensive literature about the diffusion of innovations sitting at the intersection of the disciplines of economic history, and productivity studies within economics (JEL code D24, mainly). Being economists, the economists often look at proxies like patents and royalties rather than directly at individual innovations, though. The historians are better.

Vaclav Smil has summarised some research about the time required for innovations, with a focus on what he calls "prime movers", augmentations of muscle power such as wind power, water power, steam engines and turbines, electric motors, internal combustion engines and jet turbines.

His recent book "Grand Transitions" covers these, although I found his earlier "Energy In Nature and Society" to be better for some of them. The latter book also has charts of (USA) adoption curves for telephones (landlines), radios, refrigerators, color TVs and more.

In almost every case the adoption cycle falls into this 20-to-40-year duration that you have identified. Some of his innovations, like nuclear power, also saturate well below 100%.

Incidentally, the tractor is not a good example of an innovation for reasons of new capabilities. Pretty much everything that tractors did initially--pulling things, ploughing, harrowing, seeding, etc.--was done with horses and horse-powered machinery beforehand. In "Energy In Nature and Society" there is a photo of a team of 20 horses pulling a McCormick combine harvester. Tractors were also preceded by traction engines -- the same thing, except steam powered and consequently larger and heavier. New capabilities--front-end loaders, spraying equipment, etc.--came after tractors were established. Initially a tractor was a low-latency, tireless horse: you didn't have to spend an hour fetching it and harnessing it before starting work, nor did you have to manage its workload so carefully.