Where are my damn learning curves?

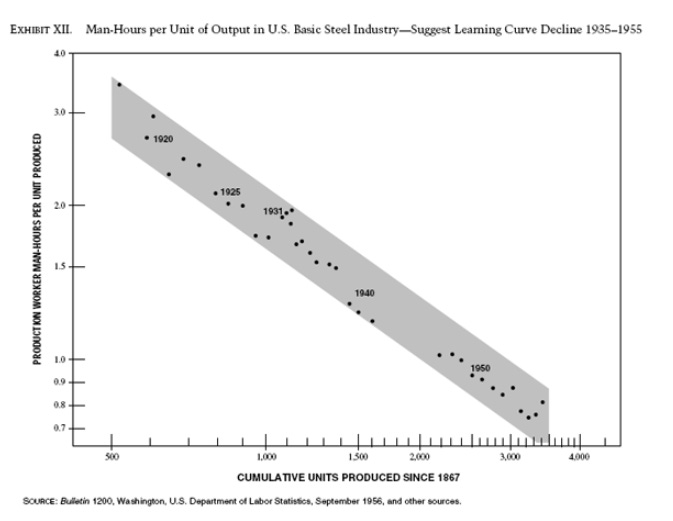

A phenomenon that shows up repeatedly in a variety of production operations is the learning curve. Essentially, the learning curve (also called the experience curve, or the progress curve) is the observation that production efficiency tends to improve at a fairly regular rate - every doubling of production volume reduces inputs (and typically costs) by some constant fraction. It was first described in a 1936 article by Theodore Wright about airplane manufacturing - each doubling of cumulative production volume (1 to 2, 2, to 4, 4 to 8, etc) was found to decrease manufacturing labor-hours by 20%. It has since been found to occur in a wide variety of manufacturing and processing environments - car manufacturing, shipbuilding, petroleum refining, electronics production, power plant construction, and steelmaking have all been shown to have learning curves at various slopes. And it shows up at a variety of different scales - we see them for individual factories, but also for entire industries. Learning curves have been found for the cumulative steel volume produced in the US, for electric power output, and for cumulative oil refined.

Between 1920 and 1980, over 100 studies of learning curve effects in various industries were performed. The learning curve appears so reliably, in fact, that businesses in production environments often expect it. Ghemawat documents a variety of companies that deliberately pursued a learning curve based strategy (scale up production, achieve market share that can then be protected by a moat of lower costs). NASA produced a handbook explaining exactly what sort of production efficiency improvements different types of operations could expect. Boston Consulting Group made learning curve-based strategies a key part of their business in the 1970s.

Given that these show up so reliably, in such a wide variety of production environments, it raises the question - where are the damn learning curves in construction? The US had approximately 45 million housing units in 1950, and has since built over 100 million more - about 1.66 doublings [0]. A learning rate of 90% would imply a roughly 17% cost decrease between now and then; a rate of 85% (same as the Model T) would imply a 25% cost decrease. If you instead calculated using something like “total residential square footage built”, you’d get even larger decreases, since average home size has steadily crept upward. But we don’t see anything like that at all.

Of the various construction deficiencies I’ve looked at, I find this one by far the most irritating. Learning curves should (theoretically) be a pure function of production volume, totally independent of production technology - if anything, some data suggests work that’s labor centric has a steeper curve (ie: improves faster) than other production systems. So where are they?

Basics of the learning curve

A basic learning curve takes the form of an equation:

Where C1 is the cost of the 1st unit, and Cx is the cost of the xth unit, with x being cumulative production volume. b is the learning curve slope, with most production environments having one between 0.6 and 0.9 (ie: a 10% to 40% improvement rate every doubling).

Different folks have added embellishments to this basic idea. Some try to accommodate the “plateau effect”, where production eventually stops improving and reaches a steady state (for reasons which will become clear, I don’t think the plateau effect is at work in construction). Some try to include a type of “experience overhang” - if you’re starting production from zero but you have a skilled operation that knows the basics, you might not see the initial improvements that a totally new operation would.

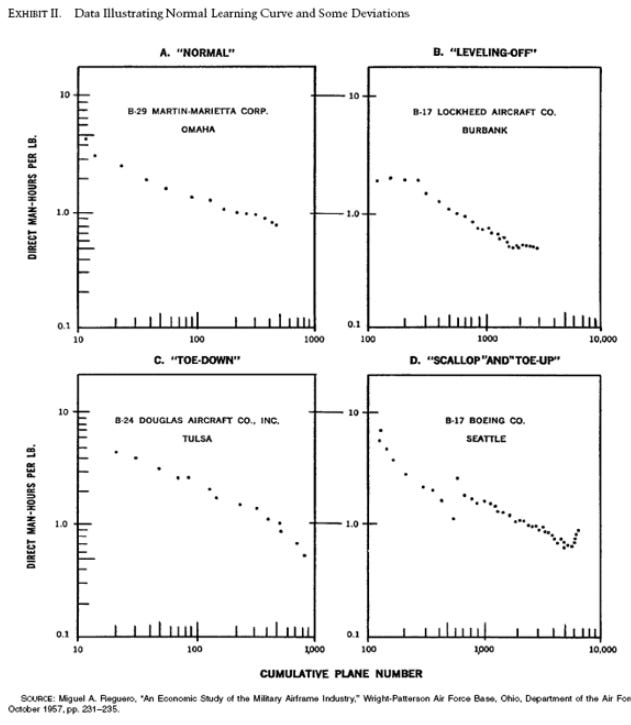

The steepness of the learning curve depends on the industry, and on the specific process arrangement. One thing that makes learning curves hard to use as a predictive tool is that the learning rate tends to vary wildly, and is hard to determine ahead of time. Even different facilities in the same industry might have different learning curves.

Types of improvement captured by the learning curve

The learning curve isn’t the result of any one improvement - it’s an abstraction over a wide range of different improvements to a given operation, and describes the manner in which those improvements will accumulate. Early on, you’ll find many improvements and increase efficiency quickly. As time goes on they become harder and harder to find. (One important caveat is that learning curves don’t ‘just happen’ - they’re the result of deliberate attempts to improve a process).

The learning curve encompasses everything we might think of as improving a process. Some improvements are due to improving technology - old machinery is replaced with new and better machinery, slow processes are replaced with new, faster ones. In this same vein, some improvements are the result of scale effects - a plant installs a larger boiler that’s more efficient than the previous one, or it spreads its fixed costs over more production volume by running a second shift.

But some productivity improvements are independent of any technological or equipment change. These are often called “Horndal Effects”, named after the Horndal iron works in Sweden, which increased output per man-hour by 2% a year for 15 years despite no new equipment or other investment. It’s hard to characterize these as one particular thing (such as workers going faster over time) - they seem to be a variety of improvements enabled by workers gradually understanding the process better, and finding additional efficiencies in it. Consider this description of a process improvement in a wrench-forging operation (via Hirschmann 1964):

In an automatic operation for forging wrenches, a piece of hot metal is forged into the proper shape in a die. With repeated use, the die “wears” or becomes larger, so that eventually the dimensions of the wrench exceed specifications and the die has to be replaced. Experience indicates the minimum number of forgings that can be made before replacement is required, and likewise the maximum number.

On the evening shift at one company, dimensions of the forgings began to vary erratically and thus indicated the need for die replacement much sooner than usual. Investigation disclosed that a new man was on the job, and that he was tinkering with the furnace temperature. When the tinkering was stopped, the die continued to perform satisfactorily. The matter could have ended there with the customary reprimand to the employee to follow instructions.

However, the investigator noted that there had been some good as well as bad results. In studying the matter, he found that the steel used could be forged at temperatures much higher than those specified without burning or destroying the properties of the metal. New dies were subsequently made smaller, and the metal first forged at the minimum practical temperature. As the die wore (got larger), the forging temperatures were increased. The hotter forgings shrank more on cooling, and in this way continued to fall within tolerance. This practice permitted a die to produce triple the normal output.

Other things in this category would be design simplification/DfMA, learning a machine’s actual capabilities (beyond its rated capabilities), and improving worker skill. In Rivethead, Ben Hamper describes pairs of workers getting so good at their assembly tasks that each is able to do both jobs simultaneously, allowing each to only work half the time.

Related to this, early stage production generally requires some amount of “working the bugs out”. von Hippel 1993 gives a number of examples of these sorts of issues at a circuit board manufacturer - in one case, the color of the parts was different than an equipment manufacturer had assumed, interfering with a camera-based sensor. In another, a layer of adhesive applied was thinner than expected, which interfered with an automatic part placement operation.

A new production environment can have any number of similar issues: a machine or process might be tweaked for the local conditions, or workers must be made familiar with a system they haven’t seen before, or a new crew must learn each other’s work rhythms, or materials used might be slightly different than expected. As time goes on, these ‘bugs’ appear with decreasing frequency and severity (since the most frequent and debilitating ones will have been found and fixed).

The point of all these examples (beyond them being interesting) is that any possible improvement can fall under a learning curve - it’s not something restricted to purely manufacturing environments. All else being equal, in a production environment I would expect to see some sort of learning curve. So what’s going on with learning curves and construction?

Learning curves in construction

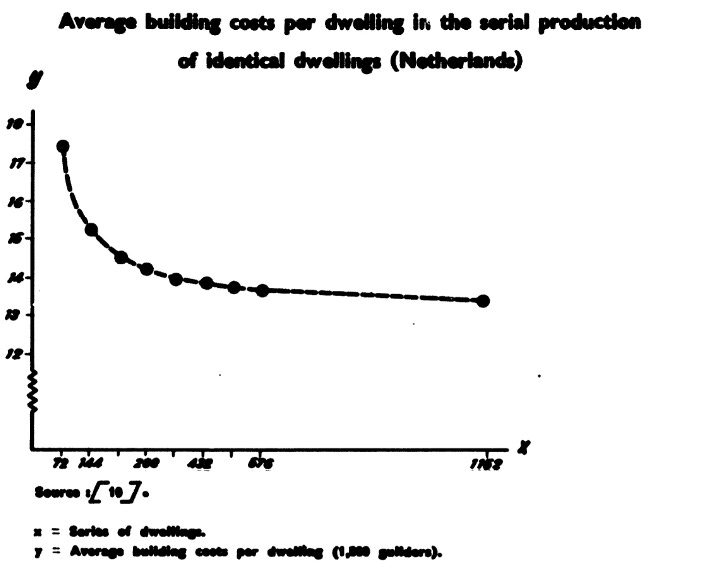

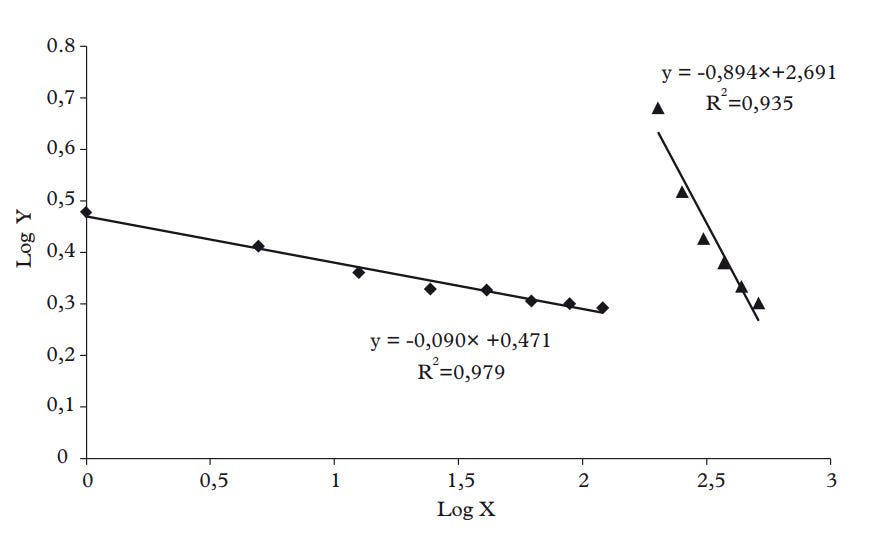

It turns out that if we go down to the level of individual building projects, we start to see evidence of learning curves. Much of the available data here comes from the 1965 UN Report “Effect of Repetition on Building Operations and Processes on Site”, which summarized time and cost studies on repetitive building operations (such as buildings with repetitive floor layouts, projects with multiple identical buildings, or repetitive tasks such as formwork construction) in a dozen different countries. In most cases, a learning curve was observed:

Thomas 2009 also gives examples of productivity increases on various projects, many of which seem to come from getting past the early ‘working the bugs out’ stage:

(Thomas in general seems to be skeptical of construction learning curves, and not all the projects he documents show them).

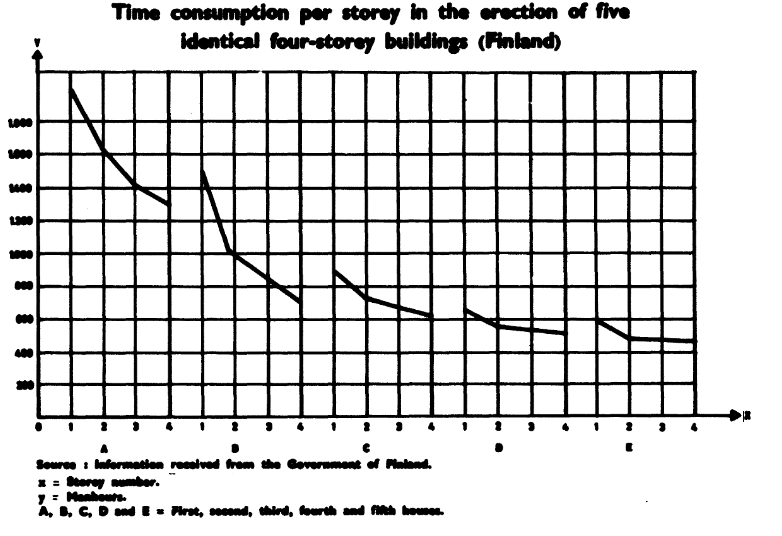

We also saw similar improvements with the Japanese skyscraper factories - later floors were constructed faster than earlier floors:

Once again, these learning curves appear regularly enough that businesses base their strategy around it - in this case, contractors will price a job assuming later work will go faster than earlier work, and sometimes use these assumptions in disputes if their work gets disrupted (i.e.: “we would have done it in this time if you had not been constantly making changes.”)

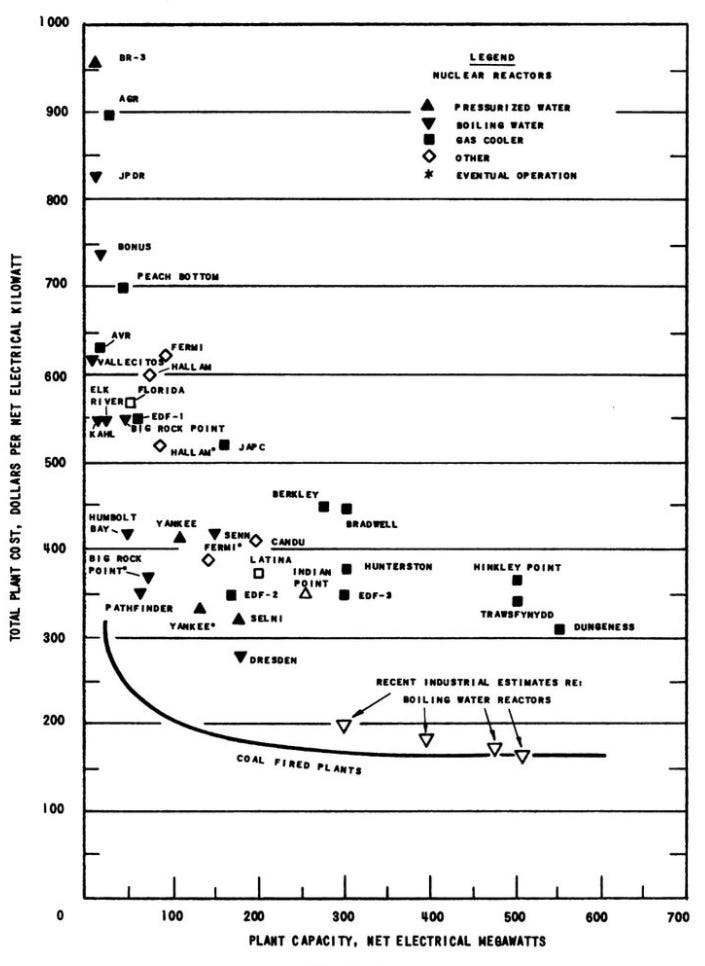

We also can sometimes find learning curves at the industry level for certain types of construction projects. Power plants especially seem to show this - nuclear power plants exhibited a learning curve up until the early 1970s:

As does the construction of wind farms currently:

Learning curve disruption

So we can in fact find learning curves in construction. So why don’t we see them reflected in gradually improving productivity, or declining costs?

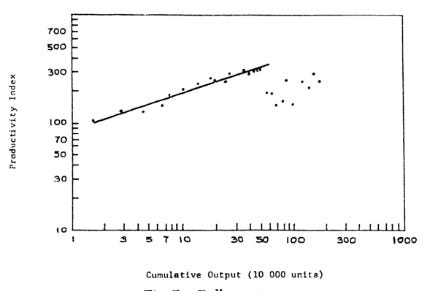

So far these graphs have shown nice smooth lines, but it’s surprisingly easy to disrupt the learning curve. Consider this graph from a clothing company, via Baloff 1970:

An apparel company exhibited a typical learning curve up until about 400,000 units. Until that point, it had been producing just a single style of clothing, but after this, it added a second style. This change to the process reset the learning curve, which afterwards continued on a downward trajectory.

The learning curve can be disrupted in a variety of ways - a new product offering, new machinery, a different work crew, or even taking a long break. Consider this example from television tube production (back when TVs had tubes), also from Baloff 1970:

Initial production was done in a single 16-week run, and shows the typical learning curve. At this point, the schedule was changed, and production was done in short segments every 8 weeks. The result was a significant resetting of productivity.

If we look at construction, we actually frequently find this disruption effect. Consider this measurement of productivity on a multistory concrete building from Pellegrino 2012:

Or this one from Couto 2004:

In both cases, construction progress initially displays the learning curve. In both cases, construction was disrupted - in the first, the site was shut down for a year due to contractor financial problems, in the second it was shut down for a week due to Easter holidays. In both cases, a significant productivity reset was observed.

Similar disruptions can be found on projects constructing a series of similar buildings. Consider this graph of a series identical apartments being constructed from the UN report:

We see an overall learning curve, both for individual buildings (later floors go faster than earlier floors) and for the project as a whole (later buildings are built faster than earlier buildings). But the curve isn’t smooth - each time a new building starts, we have a slight reset in productivity.

And we should expect most construction to have far worse resets. Most construction isn’t the same project team constructing a series of identical buildings on the same site, but is instead a new project team, a new owner, a new building layout, and a new site each time. Even something as innocuous as material variation from project to project (say, with highly variable dimensional lumber, or site-produced concrete) could be enough to disrupt the learning process - Baloff found that food-processing companies, which must cope with variable material inputs (differences in vegetables that were grown in different regions, or at different times of the year), didn’t exhibit a learning curve.

This suggests that learning curves do exist within construction, but they’re constantly being reset back to zero. Thus we don’t see any large-scale efficiency improvements as a function of total industry production volume. The fact that there are visible learning curves on individual projects also suggests this - if there wasn’t severe disruption going on from project to project, we wouldn’t see such large differences between early and later floor construction.

The takeaway here is that a learning curve exists for a particular process in a particular environment - each one has its own quirks, its own unique conditions, its own “laws of physics” that can’t be easily predicted and understood ahead of time. With experience, workers and organizations can learn the nature of these processes, improving them bit by bit (removing bottlenecks here, adding efficiency there, scaling up this part that’s working well). But this is hard to do if you’re constantly changing the process, or creating a new process from scratch every single time like construction does.

This suggests that much of the cost savings in manufactured homes (which use largely similar building systems to site-built homes) is the result of having a stable process that can be continuously improved, rather than anything particular about their production methods (which are often fairly manual).

Learning curves and technology

But circling back, we did see industry-level learning curves in some areas of construction, such as power plants. Hirschmann documents some similar improvements in the construction of chemical refineries. So how do we explain this?

I think these improvements are likely the result of a combination of new technologies and scale effects. Nuclear power plant cost per kilowatt seems to be a function of plant size - the larger your plant, the more efficient you can produce electricity, and as time goes on we build bigger and bigger plants.

We see something similar in wind power, where larger turbines are more efficient, and turbines gradually get bigger over time. But these sorts of scale effects are hard to capture with normal buildings. If you double the construction inputs to a power plant, you more than double its output, but doubling the size of a building just gets you twice as much building. Construction cost is largely a function of labor and material cost, so there’s little opportunity for spreading fixed costs over a large amount of output, and not much room for geometric returns to scale.

Things like nuclear power plants also went through significant technology change and improvements:

After nuclear fission was discovered, humanity engaged in significant efforts around the world to build economical power plants. This took about 20 years. Along the way, we experimented with dozens of different coolants, fuels, and configurations. We tried liquid metal coolant, oil coolant, molten fuel, gas coolant, nuclear superheat, sodium-graphite, sodium-deuterium, …, the whole nine yards. In the late 1950s, GE and Westinghouse achieved considerable reliability with medium-sized light-water reactors and realized that by capturing economies of scale, they could find economical power.

When there’s a fundamental shift in an underlying process, you have the potential for fairly rapid improvement. The speed of a piston-driven aircraft increased from 30 mph (the Wright Flyer) to over 500 mph (a modified P-47) from 1903 to 1944. But since then, piston-engine aircraft speed improvement has been marginal (and in fact the record is held by a modified P-51, a WWII era plane). Further speed increases in aircraft came from new propulsion systems, not further refinements to the piston engine.

We see it in semiconductor progress as well - decreasing semiconductor feature size required changing the underlying lithography techniques.

But the basic technology for how a building goes together is fairly well established at this point - successful building innovations tend to be marginal improvements on the same basic idea, not fundamentally new processes or systems.

The result is that some types of improvement that would fall under the learning curve (scale effects and new technologies) seem difficult to achieve in construction.

Conclusion:

Many production processes exhibit a learning curve - efficiency improves at a constant rate for each doubling of production volume. However, outside of some specialty buildings (like powerplants), we don’t really see this in construction. Learning curves exist for individual projects (especially ones that have repetitive elements), but not for the industry as a whole. This seems likely due to two effects. One is that learning curves are disrupted whenever a process changes, and so each time a new project starts, the process changes enough that the learning curve is reset. The other is that certain types of improvements (such as scale effects, and underlying technology changes) are more difficult to achieve in construction.

These posts will always remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work and also gain access to a members-only slack channel.

Construction Physics is produced in partnership with the Institute for Progress, a Washington, DC-based think tank. You can learn more about their work by visiting their website.

You can also contact me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or by email: briancpotter@gmail.com

[0] - Obviously some houses would have left the housing stock, and thus the “total number of houses built” would be more than 45 million - but probably not as many as we might think. Houses leave the housing stock very slowly, and the rapid population growth of the US (it went from 23 million people in 1850 to 150 million in 1950) means that most houses would have been constructed more recently.

Really good overview and write-up. The issue is that learning curves require standardization and investment. There is no entity in the current project-based real estate development model that has the control or incentive to invest. That's why the study from 1965 is still current.

Other manufacturing is of standard products. We are not close to that in residential and even further in commercial construction. A real, though minor issue, is that other manufacturers do their production inside and do not have to deal with varying site conditions or weather. We once did identical GFRC pieces as part of the roof for identical office buildings. Because the construction sequence was not identical, the GFRC project became non-identical. Connections had to be revised. One of the mysteries in all this is what happened to all the cost and labor savings from things like factory made roof trusses, telescoping fork lifts, etc. Clearly some (but how much?) went into safety., not just of workers, but of occupants. 75 years ago steel was not fireproofed, doing so adds costs.

(see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_the_Angels_School_fire).

Also "doubling the size of a building just gets you twice as much building" is inaccurate. To go from 3 stories to 6 may add a lost of cost - elevators, a stiffer structure, etc. Other example abound that call a simplistic analysis into question. Non standard products require a non standard supply chain. It adds cost and complexity.