How Did TVs Get So Cheap?

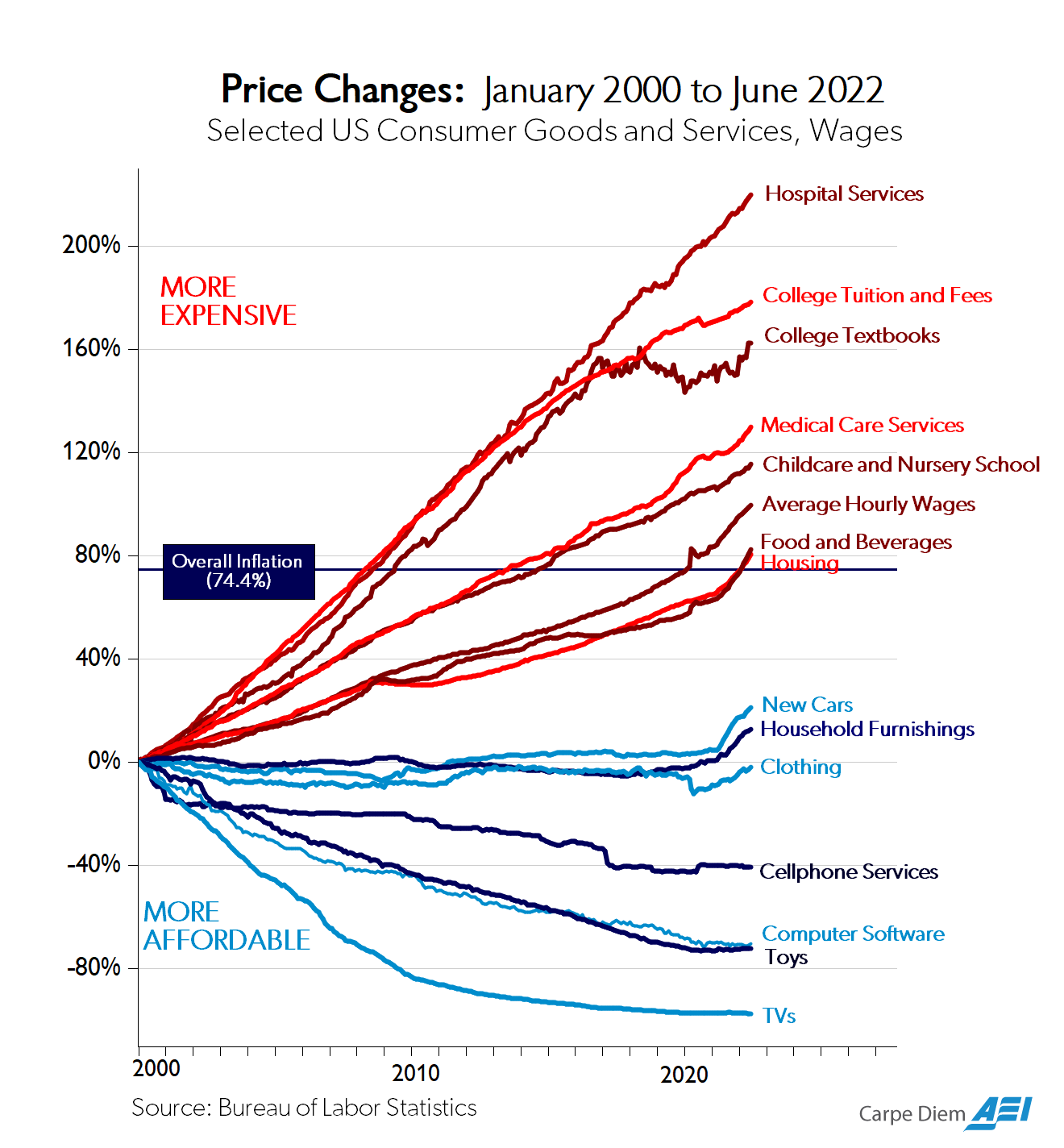

You’ve probably seen this famous graph that breaks out various categories of inflation, showing labor-intensive services getting more expensive during the 21st century and manufactured goods getting less expensive.

One of the standout items is TVs, which have fallen in price more than any other major category on the chart. TVs have gotten so cheap that they’re vastly cheaper than 25 years ago even before adjusting for inflation. In 2001, Best Buy was selling a 50 inch big screen TV on Black Friday for $1100. Today a TV that size will set you back less than $200.

The plot below shows the price of TVs across Best Buy’s Black Friday ads for the last 25 years. The units are “dollars per area-pixel”: price divided by screen area times the number of pixels (normalized so that standard definition = 1). This is to account for the fact that bigger, higher resolution TVs are more expensive. You can see that, in line with the inflation chart, the price per area-pixel has fallen by more than 90%.

This has prompted folks to wonder, how exactly did a complex manufactured good like the TV get so incredibly cheap?

It was somewhat more difficult than I expected to suss out how TV manufacturing has gotten more efficient over time, possibly because the industry is highly secretive. Nonetheless, I was able to piece together what some of the major drivers of TV cost reduction over the last several decades have been. In short, every major efficiency improving mechanism that I identify in my book is on display when it comes to TV manufacturing.

How an LCD TV works

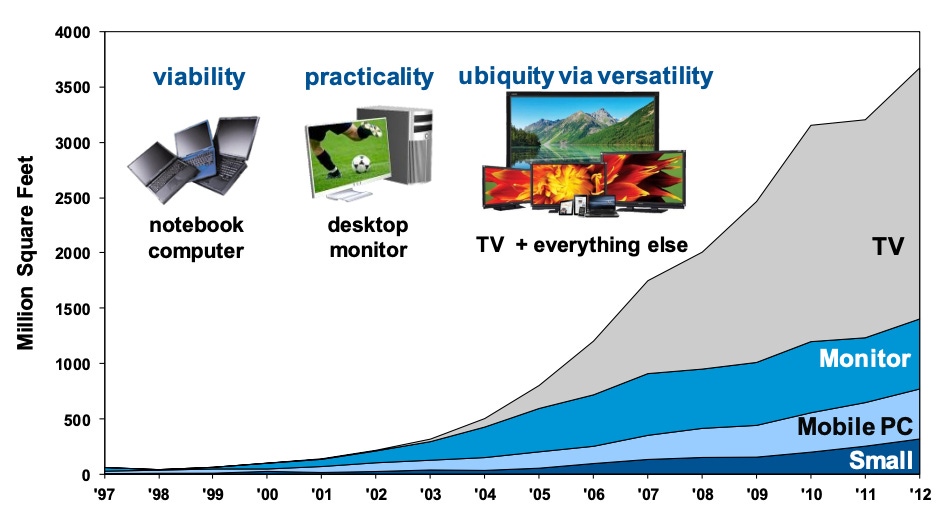

Since 2000, the story of TVs falling in price is largely the story of liquid crystal display (LCD) TVs going from a niche, expensive technology to a mass-produced and inexpensive one. As late as 2004, LCDs were just 5% of the TV market; by 2018, they were more than 95% of it.

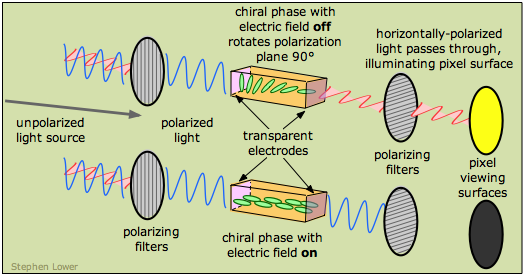

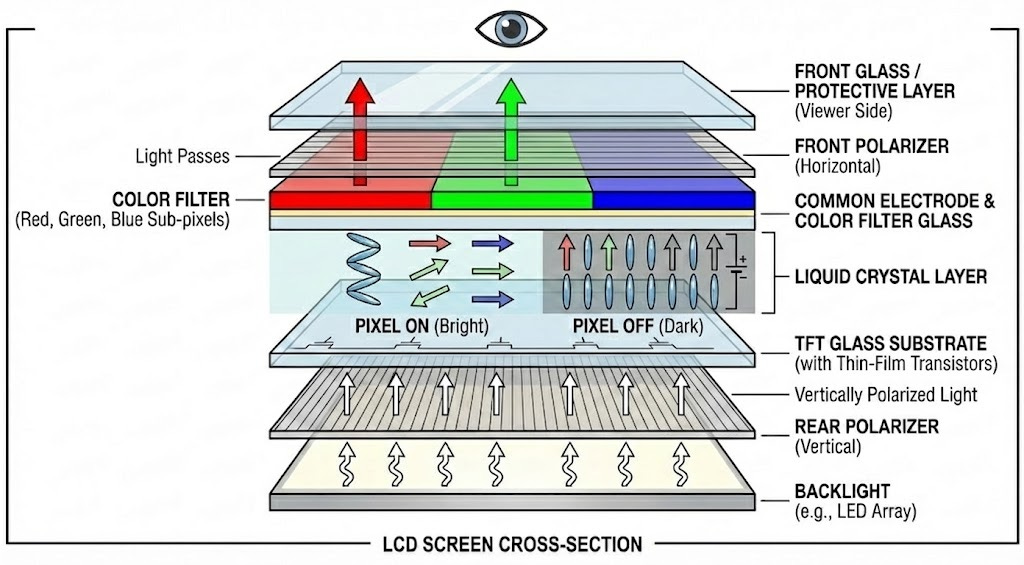

Liquid crystals are molecules that, as their name suggests, form regular, repetitive arrangements (like crystals) even as they remain a liquid. They exhibit two other important characteristics that together can be used to construct a display. First, the molecules can be made to change their orientation when an electric field is applied to them. Second, if polarized light (light oscillating within a single plane) passes through a liquid crystal, its plane of polarization will rotate, with the amount of rotation depending on the orientation of the liquid crystal.

LCD screens use these phenomena to build a display. Each pixel in an LCD TV contains three cells, which are each filled with liquid crystal and have either a red, green, or blue color filter. Light from behind the screen (provided by a backlight) first passes through a polarizing filter, blocking all light except light within a particular plane. This light then passes through the liquid crystal, altering the light’s plane of polarization, and then through the color filter, which only allows red, green, or blue light to pass. It then passes through another polarizing filter at a perpendicular orientation to the first. This last filter will let different amounts of light through, depending on how much its plane of polarization has been rotated. The result is an array of pixels with varying degrees of red, blue, and green light, which collectively make up the display.

On modern LCD TVs, the liquid crystals are combined together with a bunch of semiconductor technology. The backlight is provided by light emitting diodes (LEDs), and the electric field to rotate the liquid crystal within each cell is controlled by a thin-film transistor (TFT) built up directly on the glass surface.

Some LCD screens, known as QLED, use quantum dots in the backlight to provide better picture quality, but these otherwise work very similarly to traditional LCD screens. There are also other types of display technology used for TVs, such as organic LEDs (OLED), that don’t use liquid crystal at all, but today these are still a small (but rising) fraction of total TV sales.

It took decades for LCDs to become the primary technology used for TV screens. LCDs first found use in the 1970s in calculators, then other small electronic devices, then watches. By the 1980s they were being used for small portable TV screens, and then for laptop and computer screens. By the mid-1990s LCDs were displacing cathode ray tube (CRT) computer monitors, and by the early 2000s were being used for larger TVs.

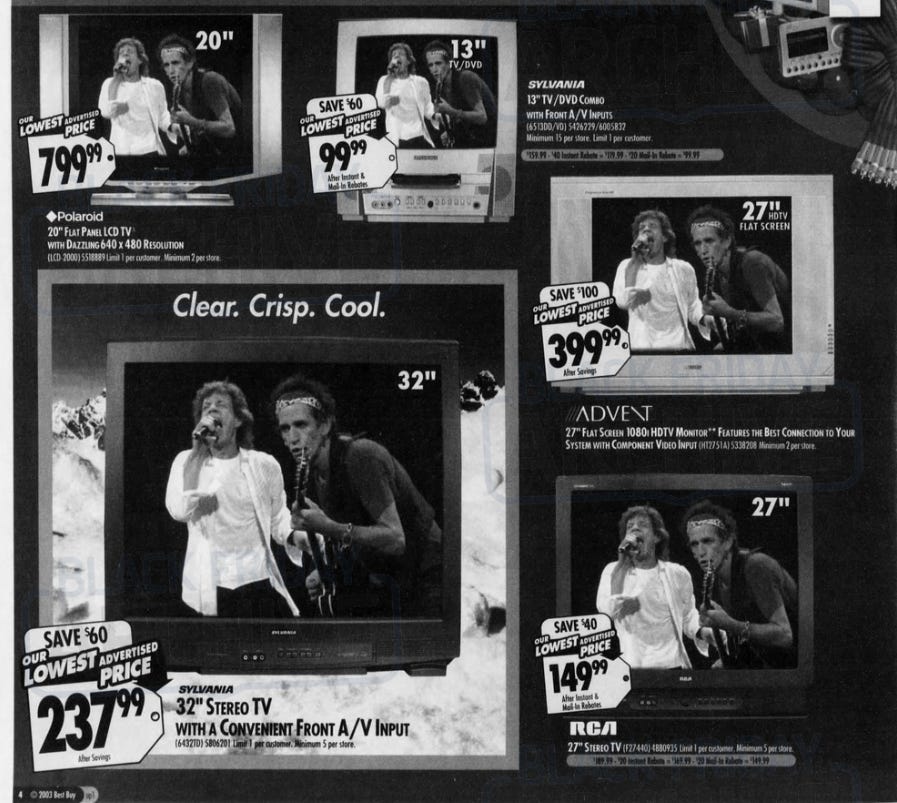

Steadily falling LCD TV Cost

When LCD TVs first appeared, they were an expensive, luxury product. In this 2003 Black Friday ad, Best Buy is selling a 20 inch LCD TV (with “dazzling 640x480 resolution”) for $800. The same ad has a 27 inch CRT TV on sale for $150. (I remember wanting to buy an LCD TV when I went to college in 2003, but settling for a much cheaper CRT).

How did the cost of LCD TVs come down?

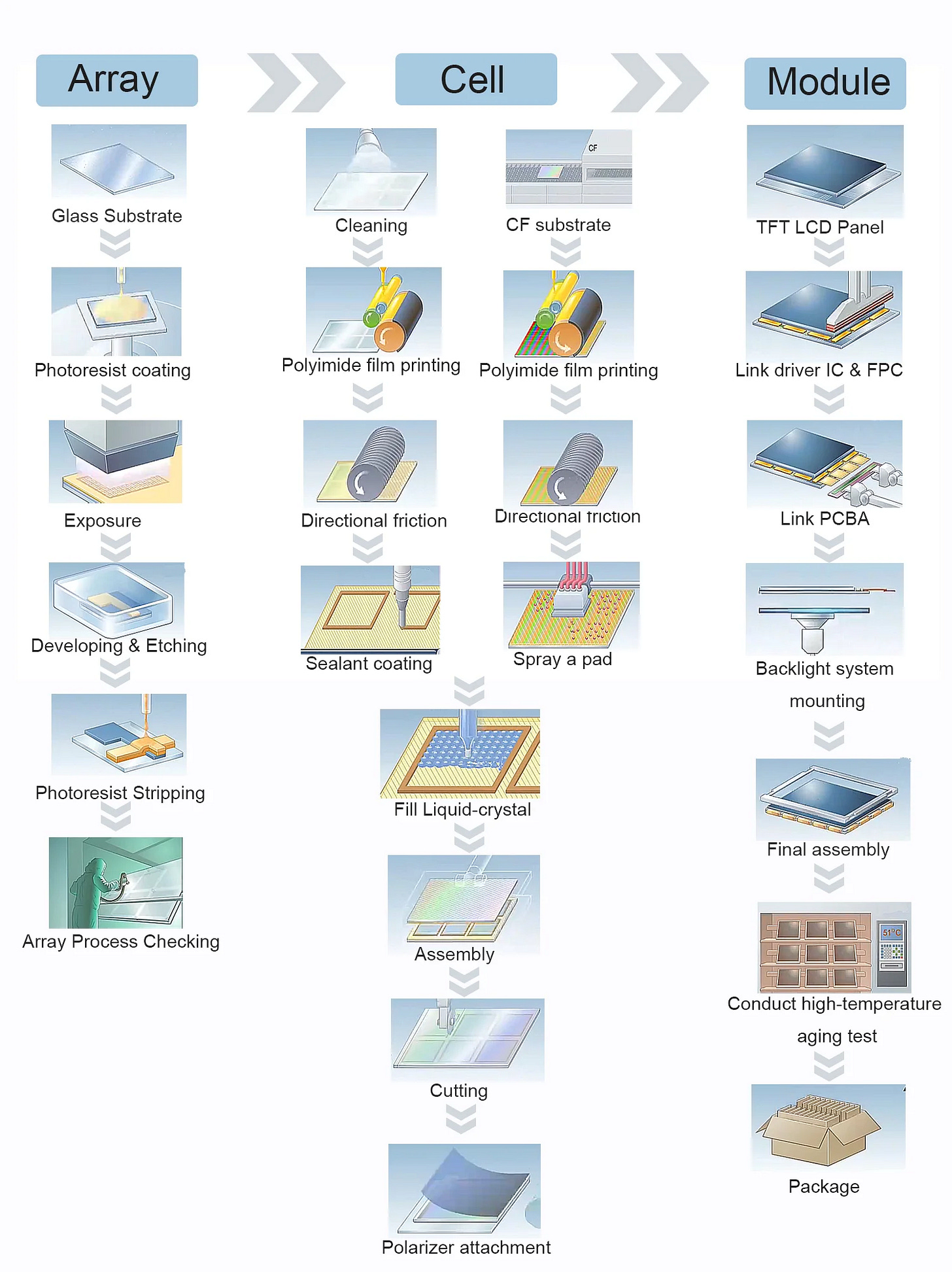

LCD TVs start life as a large sheet of extremely clear glass, known as “mother glass”, manufactured by companies like Corning. Layers of semiconductor material are deposited onto this glass and selectively etched away using photolithography, producing the thin film transistors that will be used to control the individual pixels. Once the transistors have been made, the liquid crystal is deposited into individual cells, and the color filter (built up on a separate sheet of glass) is attached. The mother glass is then cut into individual panels, and the rest of the components — polarizing filters, circuit boards, backlights — are added.

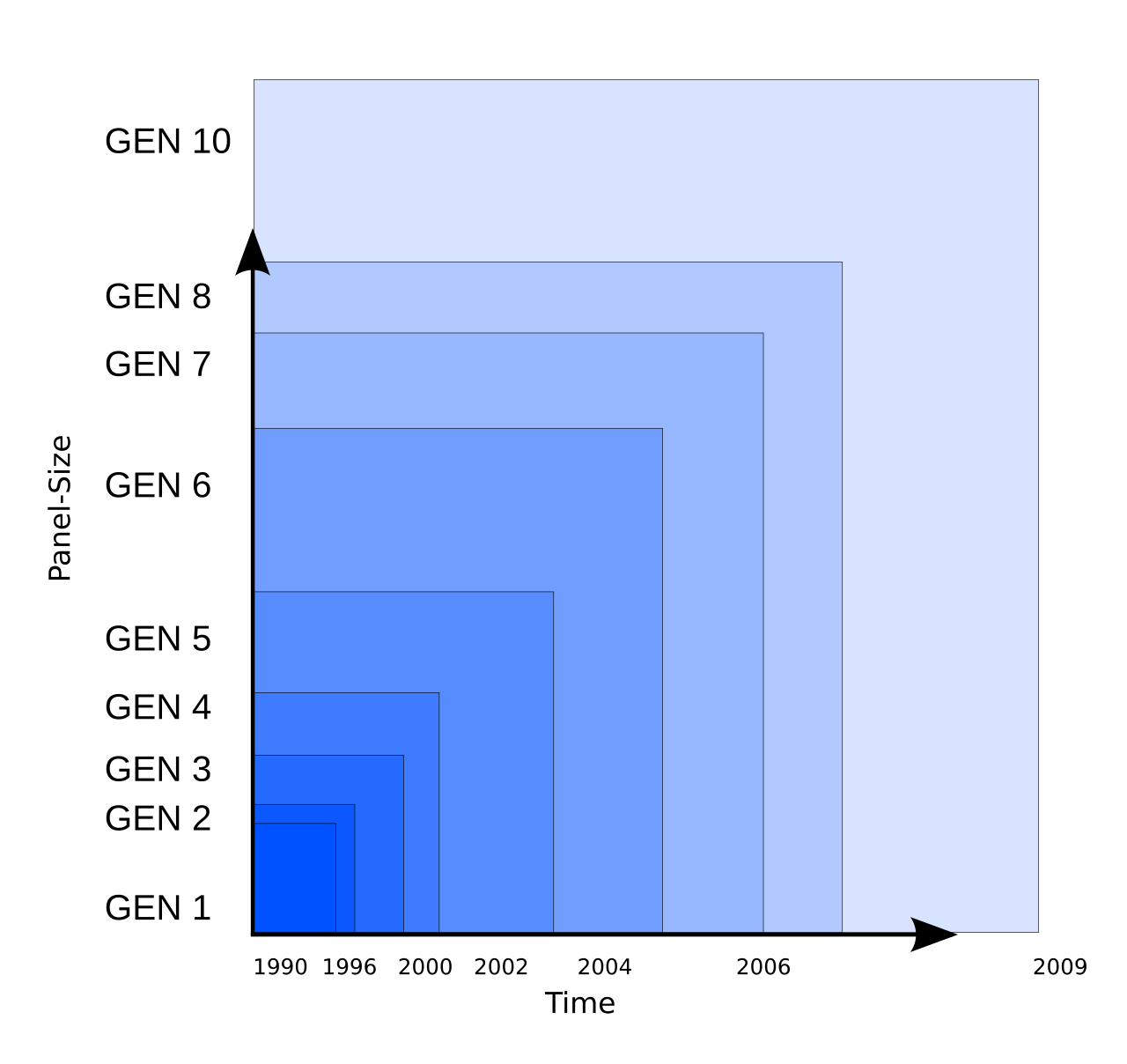

A key aspect of this process is that many manufacturing steps are performed on the large sheets of mother glass, before it’s been cut into individual display panels. And over time, these mother glass sheets have gotten larger and larger. The first “Generation 1” sheets of mother glass were around 12 inches by 16 inches. Today, Generation 10.5 mother glass sheets are 116 by 133 inches, nearly 100 times as large.

Scaling up the size of mother glass sheets has been a major challenge. The larger the sheet of glass, and the larger the size of the display being cut from it, the more important it becomes to eliminate defects and impurities. As a result, manufacturers have had to find ways to keep very large surfaces pristine — LCDs today are manufactured in cleanroom conditions. And larger sheets of glass are more difficult to move. Corning built a mother glass plant right next to a Sharp LCD plant to avoid transportation bottlenecks and allow for increasingly large sheets of mother glass.

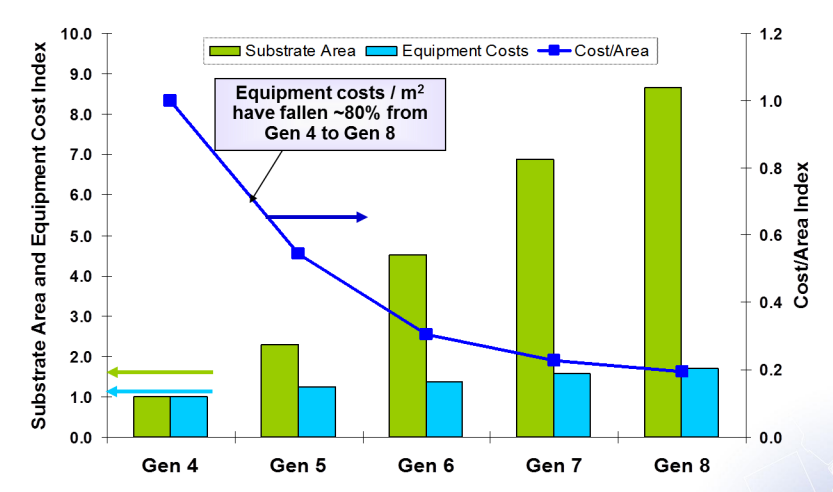

However, there are substantial benefits to using larger sheets of glass. Due to geometric scaling effects, it’s more efficient to manufacture LCDs from larger sheets of mother glass, as the cost of the manufacturing equipment rises more slowly than the area of the glass panel. Going from Gen 4 to Gen 5 mother glass sheets reduced the cost per diagonal inch of LCD displays by 50%. From Gen 4 to Gen 8, the equipment costs per unit of LCD panel area fell by 80%. Mother glass scaling effects have, as I understand it, been the largest driver of LCD cost declines.

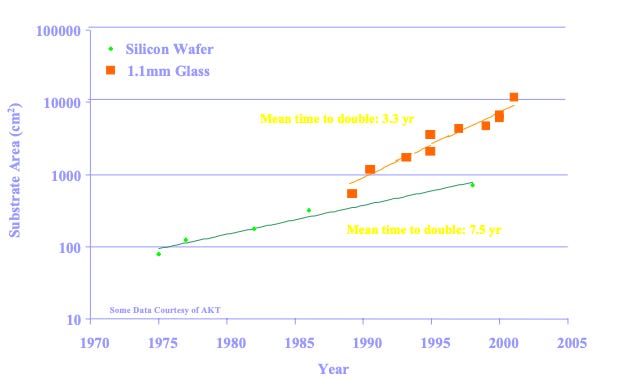

LCDs have thus followed a similar path to semiconductor manufacturing, where an important driver of cost reduction has been manufacturers using larger and larger silicon wafers over time. In fact, sheets of mother glass have grown in size much faster than silicon wafers for semiconductor manufacturing:

LCDs are thus an interesting example of costs falling due to the use of larger and larger batch sizes. Several decades of lean manufacturing and business schools assigning “The Goal” have convinced many folks that you should always aim to reduce batch size, and that the ideal manufacturing process is “one piece flow” where you’re processing a single unit at a time. But as we see in several processes — semiconductor manufacturing, LCD production, container shipping — increasing your batch size can, depending on the nature of your process, result in substantial cost savings.

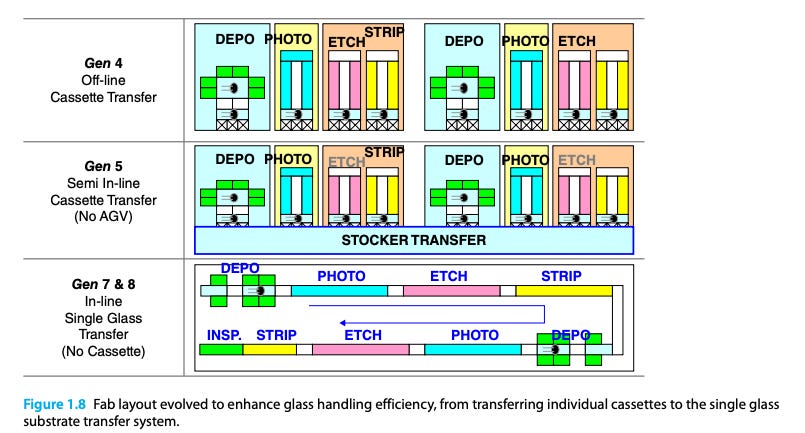

At the same time, we do see a tendency towards one piece flow at the level of mother glass panels. Early LCD fabs would bundle mother glass sheets together into cassettes, and then move those cassettes through subsequent steps of the manufacturing process. Modern LCD fabs use something much closer to a continuous process, where individual sheets of mother glass move through the process one at a time.

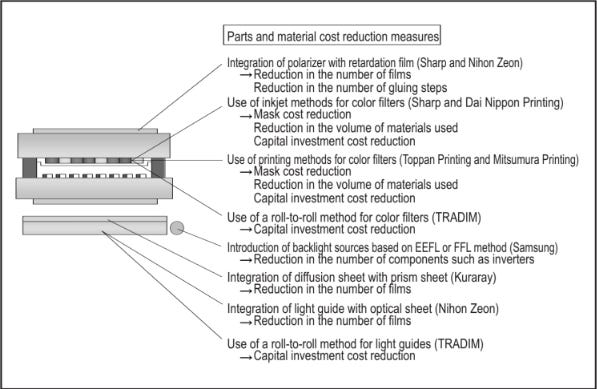

Outside of larger and larger sheets of mother glass, there have been numerous other technology and process improvements that have allowed LCD costs to fall:

“Cluster” plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) machines were developed in the 1990s for depositing thin film transistor materials. These machines were much faster, and required much less maintenance, than previous machines.

Manufacturers have found ways to reduce the number of process steps required to create thin-film transistors. Early operations required eight separate masking steps to build up the transistors. This was eventually reduced to four.

Thanks to innovations like moving manufacturing operations into cleanrooms and replacing manual labor with robots, yields have improved. Early LCD manufacturing often operated at 50% yield, where modern operations achieve 90%+ yields.

Cutting efficiency – the fraction of a sheet of mother glass that actually goes into a display — has increased, thanks to strategies like Multi-Model Glass, which allows manufacturers to cut displays of different sizes from the same sheet of mother glass.

The technology for filling panels with liquid crystal has improved. Until the early 2000s, displays were filled with liquid crystal through capillary action: small gaps were left in the sealant used to create the individual crystal cells, which the liquid crystal would gradually be drawn into. It could take hours, or even days, to fill a panel with liquid crystal. The development of the “one drop fill” method — a process in which each cell is filled before the sealant was cured, and then UV light is used to cure the sealant — reduced the time required to fill a panel from days to minutes.

Glass substrates were gradually made more durable, which reduced defects and allowed for more aggressive, faster etching.

More generally, because LCD manufacturing is very similar to semiconductor manufacturing , the industry has been able to benefit from advances in semiconductor production. (As one industry expert noted in 2005, “[t]he display manufacturing process is a lot like the semiconductor manufacturing process, it’s just simpler and bigger.”) LCD manufacturing has relied on equipment originally developed for semiconductor production (such as steppers for photolithography), and has tapped semiconductor industry expertise for things like minimizing contamination. Some semiconductor manufacturers (like Sharp) have later entered the LCD manufacturing market.

LCD manufacturing has also greatly benefitted from economies of scale. A large, modern LCD fab will cost several billion dollars and produce over a million displays a day.1 It’s thanks to the enormous market for LCD screens that these huge, efficient fabs can be justified, and the investment in new, improved process technology can be recouped.

Falling LCD costs have also been driven by relentless competition. A 2014 presentation from Corning states that LCD “looks like a 25 year suicide pact for display manufacturers.” Manufacturers have been required to continuously make enormous investments in larger fabs and newer technology, even as profit margins are constantly threatened (and occasionally turning negative). This seems to have partly been driven by countries considering flat panel display manufacturing a strategic priority — the Corning presentation notes that manufacturing investments have been driven by nationalism, and there were various efforts to prop up US LCD manufacturing in the 90s and 2000s for strategic reasons.

Conclusion

Those who have read my book will not find much surprising in the story of TV cost declines. Virtually all the major mechanisms that can drive efficiency improvements — improving technology and overlapping S-curves, economies of scale (including geometric scaling effects), eliminating process steps, reducing variability and improving yield, advancing towards continuous process manufacturing — are on display here.

Though many of these will be phone-sized displays.

Also relevant: modern TVs are large ad display and consumer behavior tracking machines which only incidentally can be used to show actual content. Proof: just monitor what the typical TV does once you connect it to the network.

The revenue from selling this mountain of data is believed to be higher than that of the actual sale (this alone is a major reason for the industry's secretiveness).

Excellent piece. Thanks for the considerable work that went into producing it.