How the Car Came to LA

Since at least the 1960s, urbanists have bemoaned the car-centric nature of US transportation. In her 1961 “The Death and Life of Great American Cities," Jane Jacobs notes that “everyone who values cities is disturbed by automobiles”1:

Traffic arteries, along with parking lots, gas stations and drive-ins are powerful and insistent instruments of city destruction. To accommodate them, city streets are broken down into loose sprawls, incoherent and vacuous for anyone afoot. Downtowns and other neighborhoods that are marvels of close-grained intricacy and compact mutual support are casually disemboweled. Landmarks are crumbled or are so sundered from their contexts in city life as to become irrelevant trivialities. City character is blurred until every place becomes more like every other place, all adding up to Noplace. And in the areas most defeated, uses that cannot stand functionally alone – shopping malls, or residences, or places of assembly, or centers of work – are severed from one another.

But of course, the US hasn’t always had cars. Fifty years prior to Jacobs’ words, only a tiny fraction of US households had cars:

So how did we become a country where cars are the defining feature of urban life? What did that transformation look like?

Answering this question for the entire country would be an enormous undertaking. But the book “Los Angeles and the Automobile” by Scott Bottles tries to answer it for LA, one of the most car-centric cities in the US. Over a period of less than 30 years, Los Angeles was transformed from a city with streetcar and train-based transportation to one where the car reigned supreme. And though Los Angeles had some unique features that made it a quicker adopter of cars than other US cities, in many ways the transformation of LA simply preceded similar transformations in the rest of the country.

US cities in the 19th century

In the early 19th century, the most common form of urban transportation was walking. Horses and horse-drawn cabs existed, but only the wealthy could afford them. Because people tend to limit their commuting time to less than one hour a day (a value known as Marchetti’s Constant), walking speed limited how much a city could grow outward, and resulted in compact, dense cities. In the early 19th century, New York, Philadelphia, and Boston had residential densities upwards of 75,000 people per square mile, compared to a current New York population density of around 26,000 people per square mile, and a current average US metropolitan area density of 284 people per square mile. In this sort of city, the suburban edge of the city was the least desirable location, as it was farthest from the rest of the city. Suburbs were considered places of “noisome industry and lowly citizens," and tended to be occupied by “objectionable industries” such as tanneries and slaughterhouses, as well as those too poor to afford to live further inward.

During the early to mid 19th century, US cities grew substantially. In the 1840s alone the population of US cities increased by 92%. As more people were packed into cities, living conditions became increasingly unpleasant. “Cesspools and overflowing sewers leaked into the drinking water of many downs while families regularly tossed their garbage into the streets." Cities were “noisy, crowded, and polluted places," with frequent disease outbreaks and reduced life expectancy.

As city conditions deteriorated, Americans (who tended to idealize both rural living and owning their own house) began to desire to move to the outskirts of the city, maintaining the advantages of city access while living in more peaceful, rural surroundings. But living on the edge of the city while commuting to the central business core required better transportation technology.

In the mid-19th century, such technology began to appear. Omnibuses, large carriages pulled by a team of horses, became popular in many large cities and allowed middle-class workers to commute to the suburbs. Horse-drawn streetcars, which were pulled along street-mounted tracks, also became widely used. And many cities such as New York, Boston and Philadelphia built commuter steam railroads that linked distant suburban communities to the central city.

Towards the end of the 19th century, cities began to widely adopt the electric streetcar. Much faster than the horse-drawn streetcar or the omnibus, the electric streetcar allowed commuting distance to greatly increase, and “opened vast new areas to development." By 1902, “there were more than 800 electric streetcar systems in the US running on 22,000 miles of track," and by 1910 electric trains were the second largest consumer of electricity in the US.

Enter LA

First founded in 1781, Los Angeles was a small city through the 19th century. As late as 1880 the city had only 11,000 people, compared to almost 2 million in New York and over half a million in Chicago. But the city began to grow rapidly after the Southern Pacific Railroad connected it with the rest of the country in 1876. Between 1880 and 1930, LA grew on average around 10% per year, and from 1890 to 1930, when it hit 1.2 million inhabitants, LA was the fastest growing city in the US.

Unlike East Coast cities, Los Angeles was never a true “walking city." It grew hand in hand with the electric railway, and by 1910 boasted both an extensive local streetcar system (which operated within the city) and the largest interurban electric rail system in the world. The Pacific Electric Railway’s (PE) 1,000+ miles of track connected Los Angeles to other communities across four counties.

Because Los Angeles had grown up with mechanized transportation, it never developed the density of east coast cities. Rather than growing upwards with skyscrapers, Los Angeles spread outwards, building an “unparalleled number” of single family homes. This sprawl and low density was touted as a positive feature of living in Los Angeles:

A prominent Los Angeles businessman wrote that the region’s large suburban population proved that people moving to California ‘prefer to live away from the noise and turmoil of the city, and that the five and six room house takes precedent over the flat or the apartment.’ Many argued that continued emigration to the city depended upon the availability of such houses. ‘Los Angeles’ future depends upon the suburban cities surrounding it,’ wrote yet another businessman. ‘The ideal life that we have here is the country or home life with your gardens and bungalows.’ By the late twenties, almost every city official and planner approved of this spatial orientation because such an environment allowed the area to avoid the crowded and unhealthy aspects of eastern urban life. People flocked to Los Angeles, commented one city official, to ‘escape the discomfort and inconvenience of living in our older cities.’

Because of this sprawl, LA residents were highly dependent on the streetcar for transportation. In 1911, residents averaged twice as many streetcar rides as residents of other large US cities.

This reliance made LA residents sensitive to the quality of streetcar service. In what Bottles describes as a “love-hate relationship," LA residents had numerous complaints about the electric rail companies they depended on:

Critics of the traction companies accused railway officials of bribing City Council members, disregarding the public’s safety, ignoring the community’s needs, abusing their franchise privileges, and profiting at the public’s expense…Indeed, the PE [Pacific Electric] hauled freight across lines granted solely for passenger trains, refused to pave the roadway in between their rails as required by their franchises, and even laid down tracks on streets before obtaining the city’s permission.

The largest number of complaints targeted crowded car conditions. Especially in morning and evening rush hour, cars were frequently full, to the point that passengers were forced to stand crowded together or even hang off the side, conditions which one newspaper described as “little short of disgraceful."

Streetcar movement was also often slow, and cars would get congested along LA’s narrow roads, particularly during rush hours. Because both local streetcars and interurban trains shared the same tracks, streetcar movement was often blocked, and there would be “long lines of streetcars backed up on downtown streets." An expert investigation of LA’s traction companies found that “fully 40,000 riders on both systems are delayed from five to forty minutes during the rush hours each day, and as many more are inconvenienced during the non-rush hours due to the fundamental defects of the transportation arrangements along Main Street.”

Many problems with the electric railways ultimately stemmed from the owners’ use of them for real estate speculation. Instead of building “efficient, rational transportation systems," traction companies would often buy large tracts of land on the outskirts of the city, and then build rail lines to connect them to the central business district, making the land more valuable. The resulting real estate development was so lucrative that one railroad magnate, Henry Huntington, was able to “make millions of dollars in real estate investments despite the substantial losses of his interurban and streetcar empire." LA’s electric railways thus developed as a series of lines radiating from the central business district, forcing passengers to navigate through the city center to get anywhere else in the city. When asked to build crosstown lines, the rail companies countered that “only those lines entering the city could attract enough riders to make them self-sufficient."

But even when focusing their attention on high-ridership lines, the electric rail companies themselves consistently performed poorly financially. In their book on electric interurban railways, George Hilton and John Duf note that “those who had faith in them paid dearly…no industry of its size has had a worse financial record." Local streetcar companies did not fare much better, in LA or anywhere else:

Electric railway construction was very expensive, even more costly than that of steam railroads…By 1910 the overall debt figures for most companies ran at about 50 percent of their total assets. As a result, Los Angeles’ railways, like traction companies throughout the United States, found it increasingly difficult to attract investment capital…The high debt ratio also made the railway companies unprofitable because of high interest charges. Between 1912 and 1940 the PE…averaged annual losses of more than $1.5 million, while turning a profit only three times. The LARY fared a bit better, but it never showed the rates of return expected of it.

“Mass transit by the second decade of the twentieth century," Bottles argues, was “simply not profitable."

Because of their poor financial performance, electric rail companies were unable to finance expansion of their systems. Between 1913 and 1925, the LA Railway Company (the city’s main streetcar operator) built only 24 miles of track, a period during which the city doubled in population. This made it nearly impossible for the electric rail companies to improve their service.

The turn to the automobile

As the electric rail companies were struggling, another mode of transportation was becoming more and more attractive: the car. In 1905, there were just 77,000 passenger cars in the US. Ten years later, in part due to the enormous success of the Model T, that had risen to 2.3 million.

A popular early use of the car for public transit was the jitney. Car owners would pick up passengers (often waiting at streetcar stops) and drive them to their destination for the same price as a streetcar ride (5 cents). Car owners would often simply put their destination in their windshields, and pick up anyone along the way who was headed in the same direction. Because jitney travel was much faster than streetcars, and wasn’t limited to the fixed streetcar routes, jitneys often had better service than streetcars.

Jitney travel first appeared in Los Angeles in 1914, and by November of that year was being used for thousands of trips per day. The jitney quickly spread to other cities. By early 1915, an estimated 62,000 jitneys operated around the country in cities such as San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, and Birmingham. As jitney travel became more popular, electric rail companies found that they were losing significant ridership:

The Seattle Electric Company estimated it was losing $2,450 per day in revenue to the jitneys, and the Puget Sound Traction Light and Power company in the same city anticipated 20,736,000 fewer fares in 1915 than in 1914. The Houston Post expected the Houston Electric Company to suffer a reduction in gross of $250,000 in 1915. California lines as a whole were losing revenue at the rate of $2,500,00 per year, and companies in the Pacific Northwest cities at the rate of $1,500,000 per year. - Eckert and Hilton

What’s more, since streetcars generally charged a flat fare regardless of travel distance, jitneys specifically targeted the short-distance riders whose fares subsidized the trips of longer-distance passengers, imperiling the already weak economics of the streetcars.

In response, LA’s streetcar operators lobbied the city government, arguing that unlike the streetcars, the jitneys did not have to pay taxes or licensing fees (denying the government tax revenue), adhere to specific routes or timetables, or maintain the roads. They also noted that the rise of jitney transport also “produced an increase in accidents in virtually every city."

The city government largely agreed with the streetcar operators, and passed legislation that required jitneys to “carry insurance, follow regular routes and timetables, and stay out of the congested downtown area." The added costs of these requirements effectively ended jitney transit in Los Angeles. Similar developments took place in other US cities, with municipalities adding restrictions on jitney transit to protect the streetcar companies.

But this didn’t stop the increasing adoption of cars. As cars got cheaper and higher-quality (the cost of a Model T fell from $950 in 1910 to $290 in 1925), and as Americans got richer (between 1913 and 1928 US GDP per capita increased 24%), car adoption exploded. By 1925 the number of cars in the US had risen to nearly 20 million.

Los Angeles was especially quick to adopt the car. By 1920 Los Angeles had the highest per-capita rate of car ownership in the US, four times more automobiles per capita than the US average, and eight times more than the much-denser Chicago. In 1920, 9 times as many people entered downtown LA via streetcar as via automobile. By 1924, that had nearly equaled.

Increasing adoption of cars was made possible by state and nationwide efforts to improve the quality of roads. As late as 1896, there were fewer than 100 miles of improved roads in California, most of which were unpaved. The “Good Roads” movement, which had been begun by bicyclists in the late 19th century, was taken up by car manufacturers and owners, and by 1919 government spending (federal, state, and county) on road construction had reached $375 million a year. As is typical, Los Angeles was early to this trend: by 1915 all of the main roads in Los Angeles had been paved.

The rapid adoption of the car, along with LA’s continued population growth, created enormous traffic congestion problems in the city. As early as 1918 the congestion caused by cars was recognized as a major problem in the downtown area. Large numbers of cars clogged the city streets, and different types of traffic on the same roads interfered with each other: cars blocked the passage of streetcars, and vice-versa. Like most cities, LA’s streets had never been designed to handle large volumes of car traffic, and LA in particular had a much smaller percentage of its area devoted to streets than other cities.

An effort to reduce congestion by limiting parking in the downtown area to off-peak hours had limited effect. Citizens argued that the traffic threatened “the prosperity of the city itself," and that the “onward march of Los Angeles towards its place of destiny will be made immeasurably slower unless a solution is found for the traffic problem." Other cities around the country faced similar problems of congestion, but LA’s congestion problems were “exceeded by no other city."

Historically, street improvement took place in Los Angeles when property owners adjacent to the streets petitioned the city council. Property owners would also typically pay for the improvements themselves. But this piecemeal approach couldn’t address the systemic congestion problems in the city. Los Angeles’ Traffic Commission (a voluntary advisory body formed in 1921) hired a group of consultants to create a plan for citywide street improvement. Their proposed Major Traffic Street Plan ultimately recommended 200 separate projects for “widening, opening, and extending of several hundred miles of streets in the city and the county." The plan was projected to cost $25 to $50 million ($450 to $900 million in 2023 dollars), and it received overwhelming support from the citizens of Los Angeles. Both the Major Street Plan and a $5 million bond issue to raise money for it passed with overwhelming margins when placed on the ballot. A year and a half later, a property tax to raise additional money for the plan also passed, “in an election where all other bond issues on the ballet went down to defeat." Property owners throughout the city submitted signed petitions for improvements to begin on their streets, and it was supported by civic groups, business leaders, and “every major city newspaper”:

The Traffic Commission…managed to bring together many of the most powerful interest groups within the region, including the downtown businessmen, the city’s homeowners, traction company officials, and supporters of mass transit. All of these groups believed that the street construction program would benefit them by easing congestion. They also realized that the automobile now played a major role in the region’s transportation system.

To facilitate the improvements, the city government passed laws that made it easier to condemn property, allowed the city and county governments to pool funds, and let the city “overrule majority protests” which prevented “intransigent homeowners” from stopping improvements. The city also hired a consultant to rewrite the city’s traffic code. Other cities around the country, facing automobile congestion problems in their own downtowns, would adopt similar traffic improvement plans.

However, the plan authors cautioned that “it was improbable…that the city could increase the capacity of the streets beyond the ability of the public to purchase automobiles," and that, “even if a city doubled the width of its streets, traffic would eventually rise to its previous level of intensity." As city streets were widened and rationalized, traffic conditions improved temporarily, but by 1930, “the Traffic Commission once again despaired that ‘traffic conditions, particularly in the downtown area, are becoming chaotic…[and] business interests and the general public are complaining bitterly in many instances.’" Street improvements had made it possible for more people to drive in LA, and had facilitated its continued population growth, but they hadn’t ultimately solved the congestion problem.

The struggle of mass transit

As LA’s streets improved, people increasingly opted to travel by car rather than by streetcars or interurban trains. By 1930, ridership on both the local LARY and the interurban PE had fallen to less than half their peaks.

Nevertheless, streetcars and interurbans continued to carry millions of people in LA, and it was widely assumed that they would continue to play a critical role in LA’s transportation infrastructure. Following the success of their Major Street plan, the Traffic Commission and the city council commissioned another consultant report for improving the city’s mass transit infrastructure. The report found that Los Angeles was a challenging city for mass transit: unlike other cities, LA’s population was widely dispersed in single family homes, and the resulting low density made a mass transit system challenging:

…rapid-transit lines could not operate self-sufficiently in the absence of high population densities. Even cities such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia found it necessary to subsidize their systems. It was doubtful that Los Angeles, with its low population density, could do otherwise.

Furthermore, even though city streets were being improved, they were still being shared by many different classes of vehicle, with “integration of streetcars, interurban trains, automobiles, and trucks result[ing] in frequent delays and extensive congestion."

The consultant’s report ultimately recommended segregating different kinds of transit, removing streetcars from roads and replacing them with elevated trains or subways, and extending rail lines to areas where they didn’t currently reach. Altogether, the improvements were estimated to cost $130 million ($2.3 billion in 2023 dollars).

But while there had been widespread agreement about the necessity of improving LA’s streets, there was no such agreement on how to implement mass transit improvements. Elevated trains were cheaper, and favored by some local business groups, but they were heavily opposed by others (such as the “Taxpayers’ Anti-Elevated League”) who believed that elevated trains “would halve property values within one half-mile of the tracks and mar the beauty of the city." One reporter wrote that “an elevated is a many-legged and roaring steel serpent and should be shunned by all cities for the machination of the devil it is."

Subways didn’t have such problems, but they were two to four times as expensive to build. Critics noted that “New York City…had spent about $1 billion on its underground system. Yet it continually lost money and required substantial public subsidies to operate." Because of the traction companies’ financial struggles, it was impossible for them to finance the construction of an underground system themselves, and residents widely opposed either subsidizing their operations or being forced to pay for the improvements themselves.

More broadly, a mass-transit system tended to favor a centralized city structure, with lines radiating from a central downtown area. Historically, businesses had clustered together to reduce transport and coordination costs, and workers had lived either in close proximity or along rail lines connected to them. However, with modern technology, such centralization was less and less necessary. With the car, it became possible to quickly travel between any two points, rather than along a fixed track. The truck greatly reduced the cost of moving goods between factories, and electric power made it possible to cheaply move power long distances, and incentivized factories to adopt low-rise, large footprint structures to rationalize the flow of material through them, making suburban locations more attractive.

As technology was making a decentralized, spread-out city more feasible, many felt that such a city would be more desirable. The Los Angeles City Club argued that “Los Angeles should reject the centralized city structure of eastern cities in favor of a ‘harmoniously developed community of local centers and garden cities’." The famous city planner Clarence Dykstra likewise argued that LA should “develop into a region of small-self-contained suburban centers…In such a structure, city life would not only be tolerable, but delightful.”

Ultimately, the coalitions that had come together to make LA’s street improvements possible did not exist for mass transit. Disagreement over the form it would take and who would pay for it assured that “the city would not build a rapid-transit system during the next forty years." Without being able to improve their systems, the traction companies continued to struggle, and by 1938 80% of transportation in LA was provided by private cars.

Decentralization and the freeway

Thanks to the car, as well as “white flight” to the suburbs, LA would continue to spread out. By 1940, Los Angeles had one fourth to one seventh the population density as cities such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Over 50% of its residents lived in single family homes, compared to just 15.9% in Chicago.

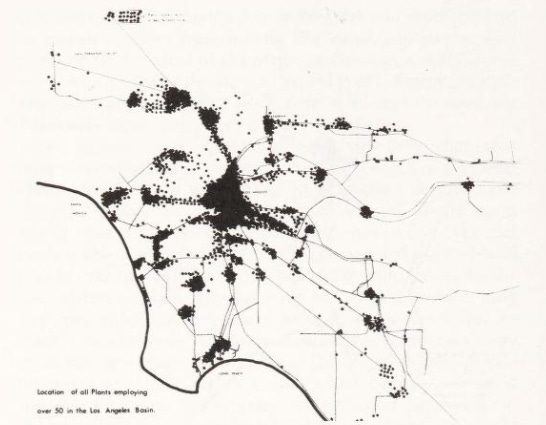

This ultimately resulted in a shift in city traffic patterns. For many years, LA and other US cities had remained centralized even as car adoption had increased, with traffic flowing towards a central business district. But as parking and congestion continued to be a problem, development increasingly took place outside the city center. Between 1930 and 1937, traffic in LA’s central business district only increased 7%, compared to over 50% in the suburbs. Department stores, which had historically occupied the downtown area, began to build branch stores closer to the suburbs. Between 1929 and 1956, the fraction of department store sales in LA’s central business district declined from 75% to 23%. And whereas in 1924 industrial plants were tightly clustered in the city center, by 1960 they were increasingly found in small clusters outside the city.

Because LA grew so late, and adopted the car so early, this pattern of development appeared there first. But ultimately most other US cities followed a similar path of decentralization. In the 1920s, 60% of new homes in the US were single family homes, and between 1938 and the beginning of WWII, this rose to 81%. Between 1948 and 1963, employment in the 25 largest US cities grew fastest outside the central city. Bottles notes that “most other urban areas in the US eventually imitated [LA] at least in part, no matter how much they may wish to deny it."

Initially, urban planners embraced the decentralization brought on by the car:

The automobile, they believed, could once and for all change the spatial organization of the metropolis. No longer would urban dwellers have to suffer from the crowded and unhealthful conditions of the walking city. Streetcars had given Americans a glimpse of the suburban ideal. Now it appeared that the automobile could fulfill the promise of residential dispersion. Furthermore, by opening subdivisions well removed from the city center, the automobile could lower population densities at the core and thus ease the burden on the urban infrastructure. The automobile seemed therefore to offer a solution to many of the problems facing city planning commissions at the time.

However, by the 1930s, city planners had realized that “something had gone wrong." Traffic congestion continued to be a problem, both in the city center and, increasingly, in suburban areas outside the city center. Land values in the central business district declined, and housing conditions deteriorated as middle-class residents left for the suburbs.

In response, planners proposed another road expansion program. But rather than enlarging existing city streets, this time they proposed a system of expressways, roads where traffic would flow continuously, unencumbered by intersections, stoplights, or cars entering and leaving at any point. Such a system would be expensive, but it would cost half as much as expanding a rail network ($2 million a mile vs $4 million a mile). And whereas a rail system always faced the specter of who would pay for it, the expressways could be financed via gasoline taxes. The fact that streetcar companies were increasingly converting their cars to diesel buses also suggested the expressway system had merit.

Construction of southern California’s expressway system was interrupted by WWII, but resumed after the war, and by 1958 southern California had completed 20% of its original plan. But as with street expansion, this ultimately didn’t solve the problems of congestion. By the 1960s, the “freeways were jammed with cars at rush hour as Angelenos had become almost totally dependent on their automobiles for transportation."

Conclusion

Bottles ends on a pessimistic note about the future of mass transit in the US. Faced with expensive rail and mass transit systems, Americans repeatedly opted for transit systems that embraced the car:

No one imposed the automobile on the public. Americans embraced the automobile willingly, for they saw it as a liberating and democratic technology. In addition, they pressured their representatives to facilitate what they believed was an important and vital method of transportation. As one might expect, the city officials eventually carried out the public’s wishes.

Bottles goes on to argue that “the same issues that prevented subway and elevated construction in the past remain with us today," and that financial difficulties have plagued the cities that have tried to adopt mass-transit systems (including LA’s). American urban residents have “long shown their disdain for public transit systems," and “it will take astronomical gasoline prices, horrendous traffic congestion, or government fiat to force most people out of their automobiles."

The book was written in 1987, but it’s not clear much has changed since then. LA, and the US, remains utterly reliant on cars. Cars per capita have continued to increase, and mass transit ridership has increased somewhat overall, but declined in per capita terms. When it does occur, mass transit construction is routinely over budget by massive amounts. The LA subway, which was finally built in the 1980s, has consistently had less ridership than expected while incurring large cost overruns.

Los Angeles and the Automobile is available on Amazon and at University of California Press.

To be fair, Jacobs goes on to say that while these failings are often blamed on the car, many of them were likely to occur to some degree even in the absence of cars.

Really good piece, thanks.

It's probably worth at least noting the urban legend/conspiracy theory about "GM bought the street car lines in LA which were how everyone got around, so they could get rid of those and force everyone to buy cars". You're far from the first person to lay out the facts which debunk it but, I literally still hear it repeated as known fact to this day. Including on social media of course.

The late urban geographer, Larry Ford, is another excellent source. I especially recommend his book Cities and Buildings: Skyscrapers, Skid Rows, and Suburbs.

One additional element that Ford adds to the story involves downtown real-estate economics during the Great Depression. Many property owners found themselves saddled with obsolete, empty buildings in the 1930s. One response was to tear down the buildings and operate the cleared lots as surface off-street parking. This was a low-risk way to generate at least enough revenue to pay property-tax bills, while waiting for a potential future opportunity to redevelop. For so many downtowns across the country, that redevelopment opportunity was slow to arrive—and many of these Depression-cleared lots remain vacant a full century later. Clearing old buildings became part of a vicious cycle, making crowded downtowns only marginally more automobile friendly while destroying the very feature—collections of high-rise real estate in dense, pedestrian-oriented clusters—that offered the historic CBD a distinctive advantage over new developments in automobile-oriented suburbs.

The Housing Act of 1949 tried to arrest this decentralization, by mobilizing federal money to fund local urban redevelopment agencies, but this largely resulted in the gentrification, or "renewal", of old "blighted" neighborhoods such as LA's Bunker Hill, further destroying downtown's historic character and displacing communities of residents and small businesses. Not until the end of cheap oil in the 1970s and the birth of a culture of "new urbanism" in the 1980s did old downtowns begin to recapture some of their lost glory from the pre-automobile era. Today, this downtown renaissance is threatened by the work-from-home habits developed during the Covid era and by new transportation technologies (e-bikes, scooters, uber/lyft, driverless cars) that divert ridership and threaten the financial viability of mass transit. We see this in LA, but the even greater California symbol of downtown's hollowing out during the 2020s is in San Francisco. Cities are remarkably resilient human creations, but it currently is hard to see how downtown SF's commercial real estate and transit (especially fare-dependent BART) can pull out of their current death spiral without massive public subsidy.