Inside the Interconnection Queue

Electric power in the US is provided by the electrical grid, a huge network of power plants, transmission lines, and transformers that moves electric power from where it's generated to where it's consumed. Before connecting a new power plant (or a very large consumer of electric power, like a semiconductor fab) to the grid, operators must evaluate whether the existing system has enough capacity to handle the change and determine what upgrades might help handle the increased load — new transmission lines, transformers, switchgears, etc. While these studies are being completed, a project must wait in the interconnection queue, a list of all projects waiting to be evaluated. Once the studies are complete, the plant exits the queue and begins construction. The interconnection queue is thus a huge list of essentially every electricity generation plant the (continental) US plans on building in the near future.1

As of this writing, there are over 11,000 projects in the interconnection queue, with a combined generation and storage capacity of around 1,900 gigawatts. This is close to twice as much generation capacity as currently exists in the US (which was 1,189 gigawatts at the end of 2023).2 Because the queue and wait time have gotten so long, the interconnection queue is a major bottleneck in getting new electrical infrastructure built, and there have been efforts to streamline and improve the interconnection process.

As a list of all planned electricity generation projects, the interconnection queue can provide a granular look at how our energy infrastructure is evolving over time, showing the kinds of projects being planned and where they’re being built. I wanted to look more deeply at the interconnection queue data, and I was able to do this thanks to the help of the folks at Interconnection.fyi, which tracks projects added to the interconnection queue on an ongoing basis, going all the way back to 1996(!).

Data from Interconnection.fyi shows exactly where and what type of projects have been planned and built since 1996. We can see that planned electrical infrastructure is overwhelmingly solar, wind, and batteries — these three project categories make up roughly 90% of planned generation and storage capacity and represent hundreds of billions of dollars of investment.

This wasn’t particularly surprising to me. What was surprising to me was how widespread this development is: Nearly half the counties in the continental US are planning some type of solar project, and solar makes up 40% or more of planned generation capacity in 36 US states.

Interconnection queue

Let’s start by looking at the current state of the interconnection queue. Right now there are around 11,300 projects in the interconnection queue. 10,590 of these (more than 93%) are power generation projects, with a total generation capacity of roughly 1,900 gigawatts. (“Generation” in this context means roughly “supplying power to the grid”, and includes energy storage projects like batteries.) Load projects (consumers of very large amounts of electric power) and transmission projects make up most of the balance.3

These projects are spread all across the US, but most projects — and most planned new generation capacity — are being planned in a small number of states. Texas, California, New York, Arizona, Illinois (?), Oregon (??), and Indiana (???) together are responsible for more than 50% of proposed new generation capacity.

There are a few surprises here. I was surprised to see so much planned generation in Oregon and the Midwest, and so little in high-growth Southeastern states: A single county in Oregon (Crooks County) has more generation capacity planned than more than half of US states. Indiana has a population of just under 7 million, but it has more generation capacity planned than Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina, which have a combined population of around 45 million.

There’s a similar concentration of proposed capacity by county, but it doesn’t change the overall picture much. Of the 3,244 counties in the US, more than half have an electrical generation project of at least 50 megawatts planned, but just 200 counties are responsible for 50% of planned generation capacity.

Most of these projects have been added to the queue recently. Here’s the queue broken down by how long the projects have been waiting in it:

Of the ~11,300 projects in the interconnection queue, 6,500 of them were added in the last 3 years. Over the last several years there’s been a huge jump in projects added to the interconnection queue. Between 2007 and 2015, roughly 1,000 projects a year were added to the queue, but between 2021 and 2023 that number exceeded 3,000.

Unsurprisingly, as the queue has gotten longer, wait times have increased. Prior to 2010, projects spent less than 3 years in the queue on average. Current wait times are longer than 5 years. A project currently in the interconnection queue has been there for 4.8 years on average. (However, it’s not clear if the increase in queue times is due to delays in the interconnection process, or because projects are taking longer to get approved for other reasons.)

We can observe this same trend at work if we look at regional trends. Here are the average queue wait times broken down by electricity market:

California’s CAISO is performing the worst, though the Midwest’s SPP is right up there with it, and average wait times in virtually every region have gotten worse over time. Unfortunately, this doesn’t include trends for projects in Texas’s ERCOT or New York’s NYISO market regions. (NYISO completed projects don’t include completion dates, and ERCOT completed projects don’t include the date they were added to the queue.)

Most folks are surprised to hear that we have more generation capacity planned to be built than currently exists, but most of these projects won’t ever be built. Between 1999 and 2018, 72% of the projects added to the queue were later withdrawn, a fraction that has stayed roughly constant over time (though with a lot of year-to-year variation). More recent years (post-2018) have lower withdrawal rates, though this is almost certainly because more recently added projects haven’t been around as long and just haven’t been cancelled yet.

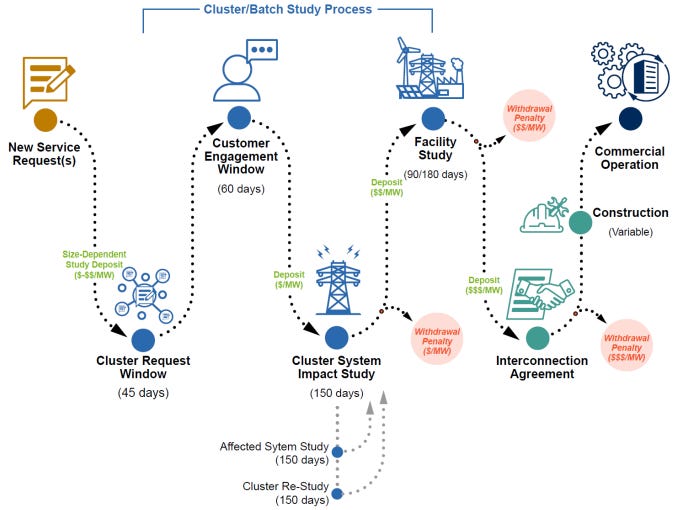

The fact that withdrawal rates are relatively constant over time suggests that more recent trends, like increasing queue length and project wait times, aren’t major drivers of project withdrawals (though it’s hard to be sure given how recent the huge increase in queue length is). Instead, high withdrawal rates seem like they have more to do with low costs of entry (so many early stage, speculative projects get added to the queue) and the high and uncertain costs of grid upgrades that must be borne by the project. Historically the grid impact of projects was evaluated one project at a time, and so a project might get unlucky and be forced to pay for grid upgrades which subsequent projects could essentially free ride on. This caused some projects to drop out if they got a bad roll of the upgrade dice. (This has hopefully been addressed by a recent FERC rule change that requires projects to be evaluated in groups and to spread the cost of grid upgrades over multiple projects.)

What sort of projects are in the queue? They’re overwhelmingly renewable energy projects — solar, wind, batteries, or some combination of the three make up around 90% of planned capacity in the interconnection queue. Natural gas plants make up another 7%, and everything else, including nuclear, oil, coal, hydrogen, and pumped hydro, make up just 3%.

Because different energy projects have different capacity factors (fraction of time they’re producing power), “capacity” doesn’t necessarily correspond to “expected output”. The typical capacity factor of utility solar PV in the US is around 25%, while for a gas plant its around 56%. So comparing purely by capacity somewhat underestimates the effective magnitude of gas plant construction and overestimates the magnitude of renewables. But even adjusting for this, renewables remain dominant.

This is a relatively recent trend. Early in the 21st century gas plants were the largest individual share of planned capacity. But by the late 2000s gas began to be eclipsed by wind power, and by the late 2010s solar projects became dominant.

We don’t see terribly much variation in withdrawal rates by project type. Between 1999 and 2018 solar, wind, gas, and batteries all have similar withdrawal rates. Battery + solar projects actually have substantially lower withdrawal rates than other types of projects:

Most planned projects are on the smaller side. Of the 11,000+ projects in the interconnection queue, roughly 8,000 of them will have a generation capacity of 200 megawatts or less, and the average capacity of a generation project in the queue is around 180 megawatts. But there’s significant variation by project type. Wind, gas, and offshore wind projects tend to be larger, while solar and battery projects tend to be smaller.

If we look at a geographic spread of queued projects by project type, we see that solar projects are very broadly distributed. 36 states have 40% of their planned capacity or more as some flavor of solar. It’s not just sunny states that are building solar projects — it’s everywhere.

Wind projects are more concentrated, but still fairly broadly distributed. 18 states have wind projects as 20% or more of their planned generation capacity.

By comparison, gas projects are sparser. Not only is their planned capacity less than that of solar, wind, and batteries, but they’re not nearly as widely distributed. Only seven states have gas plants as more than 20% of their planned generation capacity. (If we adjust for gas’s higher capacity factor, this is perhaps closer to 13 states.) And while over 1,500 counties are planning on some type of solar project, only around 200 counties are planning a gas project.

Conclusion

We’re witnessing the early stages of a historic buildout of energy infrastructure, with thousands of gigawatts worth of generation projects currently in the pipeline. Assuming these projects withdraw from the queue at historic rates, currently planned projects alone can expect to increase the US’s electricity generation capacity by around 50%.

Some back of the envelope numbers suggest that the current interconnection queue represents around two trillion dollars’ worth of energy investment.4 Even if you only count projects that will likely ultimately get built, that’s still on the order of $600 billion. These projects are overwhelmingly solar, wind, and battery projects, and they’re spread all across the US, in virtually every state.

The interconnection queue shows both the good and the bad of the Trump administration’s energy policies. The huge influx of projects has driven up queue waiting times, and we desperately need to make approvals and permitting go faster to build the amount of infrastructure we need. The changes to the CEQ rules can potentially help here.

However, stalling permitting for solar and wind projects has the potential to do immense harm. These aren’t niche technologies being adopted by a handful of blue-leaning states; they’re the backbone of the energy infrastructure we’re building, represent hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars of investment, and are a major economic driver in virtually every state in the union. Many of the Trump administration’s early executive orders addressed the energy emergency currently facing the US, but slowing down or stopping wind and solar permitting could make such an emergency catastrophically worse.

Thanks again to the folks at Interconnection.fyi who provided the data for this analysis.

As far as I can tell, projects in Alaska, Hawaii, or US territories aren’t included in the interconnection queue, though some Canadian and Mexican projects are.

One complicating factor with this comparison is what while both values include energy storage, that 1,900 gigawatts includes far more energy storage than exists on the grid today, which is mostly small amounts of pumped hydro storage.

From what I can tell, most utilities aren’t actually tracking the connection of large load projects. Only the Bonneville Power Administration is reliably tracking them.

An excellent overview of the topic of electrical interconnection queues.

A few additional points:

1) There is a huge difference between Capacity (the unit used in this article) and the actual amount of electricity generated. This is particularly true for renewable sources. This means that you cannot really compare generators in the queue with existing generators, which have far higher capacity factors.

2) Batteries do not actually generate electricity, so their capacity is very different from electrical generators. Batteries merely store electricity.

3) I think the shift to renewables is a big part of the problem with the increased wait time. It is far easier to connect and make modifications to the existing grid when you are trying to add on a single-point dispatchable electrical generator that is close to urban areas, such as natural gas, coal, or nuclear, than a widely-spread, geographically distant, and intermittent electrical generators, such as wind and solar.

4) The fact that solar is widely spread across the nation shows that much of this production is chasing government subsidies and mandates. Solar should be concentrated in regions of high solar radiance, such as the Southwest, not widely scattered across the states with much lower solar radiance.

Glad our data was helpful in your analysis!