Reading List 12/13/2025

Boom Supersonic’s gas turbine, the reliability of learning curves, a fake bridge collapse, using coal mines for geothermal energy, and more.

Welcome to the reading list, a weekly roundup of news and links related to buildings, infrastructure, and industrial technology. This week we look at Boom Supersonic’s gas turbine, the reliability of learning curves, a fake bridge collapse, using coal mines for geothermal energy, and more. Roughly 2/3rds of the reading list is paywalled, so for full access become a paid subscriber.

Boom announces a gas turbine

Supersonic jet startup Boom Supersonic, which we’ve previously talked about, announced this week that they’re going to be using their engine technology to build gas turbines to help power the AI boom. From Tom’s Hardware:

The Superpower turbine is purportedly “optimized for AI datacenters,” a claim boiled down to delivering its full 42 MW with 39% efficiency, at an operating temperature up to a toasty 110° F (43° C). Judging by a quick search, that’s significantly higher than contemporary designs, whose output drops at around 86° F (30° C), if not much sooner—and precisely when it’s most needed, when servers are working the hardest.

Boom says it’s taken an order for its new design from Crusoe AI for a substantial 1.21 GW of turbines. The company says it builds everything in Denver, Colorado, and that it intends to create a Superfactory for this new enterprise. Boom expects to deliver 200 MW worth of turbines by 2027, 1 GW in 2028, and up to a meaty 2 GW come 2029. Crusoe ordered 29 units, and the first of them ought to be delivered in 2027.

You can read a Twitter thread from Boom’s founder Blake Scholl on the turbine here.

I have a few thoughts on this. On the one hand, it’s not crazy to use a jet engine as the basis for a ground-based turbine power plant. These sorts of turbines, called aeroderivatives, already exist. It also doesn’t seem impossible that the sales from this could help fund their broader supersonic jet project: because demand for power is so high, there’s a huge backlog of orders at existing turbine manufacturers, which Boom could conceivably capitalize on. Lots of folks thus seem enthusiastic about this development.

However, it also seems like dividing focus like this might make it harder for Boom to achieve it’s ultimate goal of a supersonic airliner. There’s also the uncomfortable fact that Boom hasn’t actually built their jet engine yet: they originally planned to have the engine core (compressor, combustor, and turbine) completed by the end of this year, but that’s now been pushed to 2026. Boom has a very long history of missing delivery dates, so taking on a goal that seems like it would make it harder to meet their delivery dates seems less than ideal.

Overall, I think the ratio of hype to actual progress at Boom is still way too high.

Lars Doucet reviews “The Land Trap”

Mike Bird, a journalist at the Economist, has a new book out about land, “The Land Trap”, which “reveals how this ancient asset still exerts outsize influence over the modern world”. Lars Doucet, who wrote his own book about land, and who writes about land economics at his substack, Progress and Poverty, has a good review of it:

Mike Bird, writer for the Economist, has written an excellent book called The Land Trap, whose basic premise is that land is a big deal. If you’ve read my own book on that subject you’ll find many parallels in Bird’s, but his book has a second purpose. That purpose is to warn us of the titular Land Trap, which I expect will join other established terms like “Cost Disease,” “The Two-Income Trap”, and “The Resource Curse” in the economic lexicon.

The book can be summarized in five bullet points and one fun fact.

The five bullet points are:

Land is a big deal, and always has been

Land has only recently been financialized

Financializing land causes “The Land Trap”

It has short term benefits but devastating long term consequences

China serves as a perfect example of what not to do

The fun fact is this:

Fiat currency isn’t backed by nothing, as commonly supposed, but by land.

How reliable are learning curves?

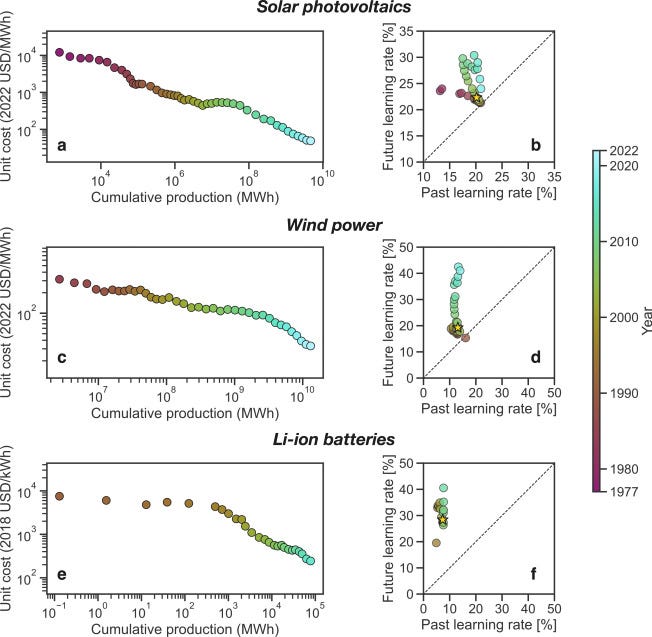

As I’ve noted both in this newsletter and in my book, learning curves — the observation that costs tend to fall by some constant percentage for every doubling of cumulative production — are an important vehicle by which things get cheaper over time. I’ve previously noted that in practice learning curves can be somewhat messy, and display a lot of variation (which gets somewhat concealed by the log-log plot used to display them). Now a new paper analyzes a bunch of historical learning curves, and finds that past learning curve performance is not predictive of future learning curve performance. From the abstract:

Climate and energy policy analysts and researchers often forecast the cost of low-carbon energy technologies using Wright’s model of technological innovation. The learning rate, i.e., the percentage cost reduction per doubling of cumulative production, is assumed constant in this model. Here, we analyze the relationship between cost and scale of production for 87 technologies in the Performance Curve Database spanning multiple sectors. We find that stepwise changes in learning rates provide a better fit for 58 of these technologies and produce forecasts with equal or significantly lower errors compared to constant learning rates for 36 and 30 technologies, respectively. While costs generally decrease with increasing production, past learning rates are not good predictors of future learning rates. We show that these results affect technological change projections in the short and long term, focusing on three key mitigation technologies: solar photovoltaics, wind power, and lithium-ion batteries. We suggest that investment in early-stage technologies nearing cost-competitiveness, combined with techno-economic analysis and decision-making under uncertainty methods, can help mitigate the impact of uncertainty in projections of future technology cost.

I’ve only skimmed this paper so far, but I plan on looking at it more closely for a future newsletter.

Fake bridge collapse

An underappreciated load-bearing aspect of modern civilization is that most people, most of the time, will act in pro-social ways. We most notice this in its absence, when this assumed pro-social behavior breaks down and things require (or are perceived to require) heavy oversight to prevent anti-social behavior, such as security screening at airports or when retail stores need to lock up their goods because of shoplifting concerns. But for most aspects of daily life, these sorts of interventions aren’t necessary.

One risk of AI is that it will dramatically reduce the cost of certain types of anti-social behavior, and empower the small fraction of folks who want to engage in it. One risk that lots of people are concerned about is using AI to create engineered pandemics, but it’s certainly not the only one.

In that vein, here’s a story about someone using AI to create a fake image of a bridge collapse, causing trains to get delayed:

Trains were halted after a suspected AI-generated picture that seemed to show major damage to a bridge appeared on social media following an earthquake.

The tremor, which struck on Wednesday night, was felt across Lancashire and the southern Lake District.

Network Rail said it was made aware of the image which appeared to show major damage to Carlisle Bridge in Lancaster at 00:30 GMT and stopped rail services across the bridge while safety inspections were carried out.

A BBC journalist ran the image through an AI chatbot which identified key spots that may have been manipulated.

Network Rail said the railway line was fully reopened at around 02:00 GMT and it has urged people to “think about the serious impact it could have” before creating or sharing hoax images.