Reading List for 06/07/2025

Risks to US battery storage, un-affordable affordable housing, a major Supreme Court NEPA ruling, making chip materials in space, and more.

Welcome to the reading list, a weekly roundup of news and links related to buildings, infrastructure, and industrial technology. This week we look at risks to US battery storage, un-affordable affordable housing, a major Supreme Court NEPA ruling, making chip materials in space, and more. Roughly 2/3rds of the reading list is paywalled, so for full access become a paid subscriber.

Battery storage risks

Looking at the trends in battery storage growth, and the number of battery projects in the interconnection queue, the future of the battery storage industry in the US seems like it would be bright. But apparently things are shakier than I realized. Battery storage integrator (sort of like a general contractor for battery storage) Powin, one of the largest storage integrators in the world, announced that its laying off 250 employees and suspending operators, apparently due to a combination of tariffs, potential tax credit repeal, and other issues. Via Latitude Media:

Powin designs, commissions and services utility-scale battery projects, positioning itself as what CEO Jeff Waters calls “that one throat to choke” for utilities and power producers deploying storage assets.

According to rankings from S&P, Powin had the third most gigawatt-hours of batteries installed in the U.S., in 2024, and the fourth most globally.

In January, Clean Energy Associates issued an analysis showing how the battery storage industry faced “multiple layers of policy risk,” ranging from tariffs, tax credit repeal, and Chinese content exclusions. Some large battery projects have been delayed as a result.

Developers are waiting to see the outcome of budget reconciliation later this year before moving forward with projects. Meanwhile, procurement has become increasingly complex as companies try to navigate overlapping tariff regimes and domestic content requirements.

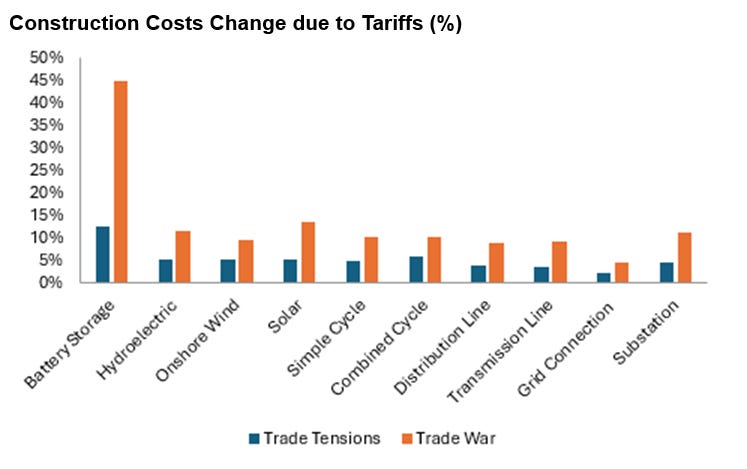

Related, Wood Mackenzie has a new report out suggesting that tariffs could drive the costs of battery storage up by 45%.

It’s not clear to me how representative the issues with Powin are of the industry more generally, but I’ll be keeping an eye on this.

Batteries in Pakistan

In other battery news, we’ve previously noted that Pakistan has one of the highest rates of solar PV installation in the entire world, in part due to an exceptionally unreliable power grid. Now it’s apparently starting to pair these with battery storage systems. From the Financial Times:

“Companies can now recover their investment in transitioning to predominantly renewable energy — using solar, wind and batteries — in less than two years.”

The battery storage systems are still too expensive to be adopted as widely as solar has been in Pakistan in the near future. But distributors say prices are falling rapidly and demand continues to grow.

Faaz Diwan, director at Karachi-based Diwan International, one of Pakistan’s largest solar and battery distributors, said the cost of the BYD batteries he sold had fallen by more than a third since last year to about Rs275,000 for a 5kWh unit that is enough to power a small house.

His company has been importing more than 500 batteries a month since March, three times more than last year, as wealthier households, gyms, mosques and businesses gobble up storage systems to save money on air-conditioning ahead of summer.

“Affordable” housing

“Affordable” housing in the US generally doesn’t mean housing that’s inexpensive to build and thus cheap: it means housing where the developer takes advantage of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (a HUD program), or other similar credits, by allocating a certain number of housing units to people with low incomes. Ironically, the overhead of this program means that in practice, “affordable” housing can be incredibly expensive to build. This article from the Washington Post describes an “affordable” housing project has development costs of $1.2 million per unit, compared to just $350,000 per unit in a building built next door by the same developer, and digs into the reasons why:

To make use of the credits, which lower a company’s tax liability dollar-for-dollar, developers typically partner with big companies, such as banks, that have tax liabilities big enough to benefit from them. While the credits are awarded in significant amounts — often tens of millions of dollars — developers typically have to augment them with various other funding sources. The resulting financing structures require small armies of lawyers and accountants to manage, driving up development costs.

While affordable housing developers and advocates privately acknowledge the program’s inefficiencies, they are reluctant to offer public criticism because, without it, tens of thousands of new affordable housing units per year would not be built.

Other cost drivers include wage requirements for construction workers that come with federal funding. There are also city requirements to hire local workers and bring on local small businesses. And the competition for public funds tends to produce smaller developments, so that the money can be spread around to numerous projects, which prevents developers from benefiting from economies of scale.

US housing affordability by county

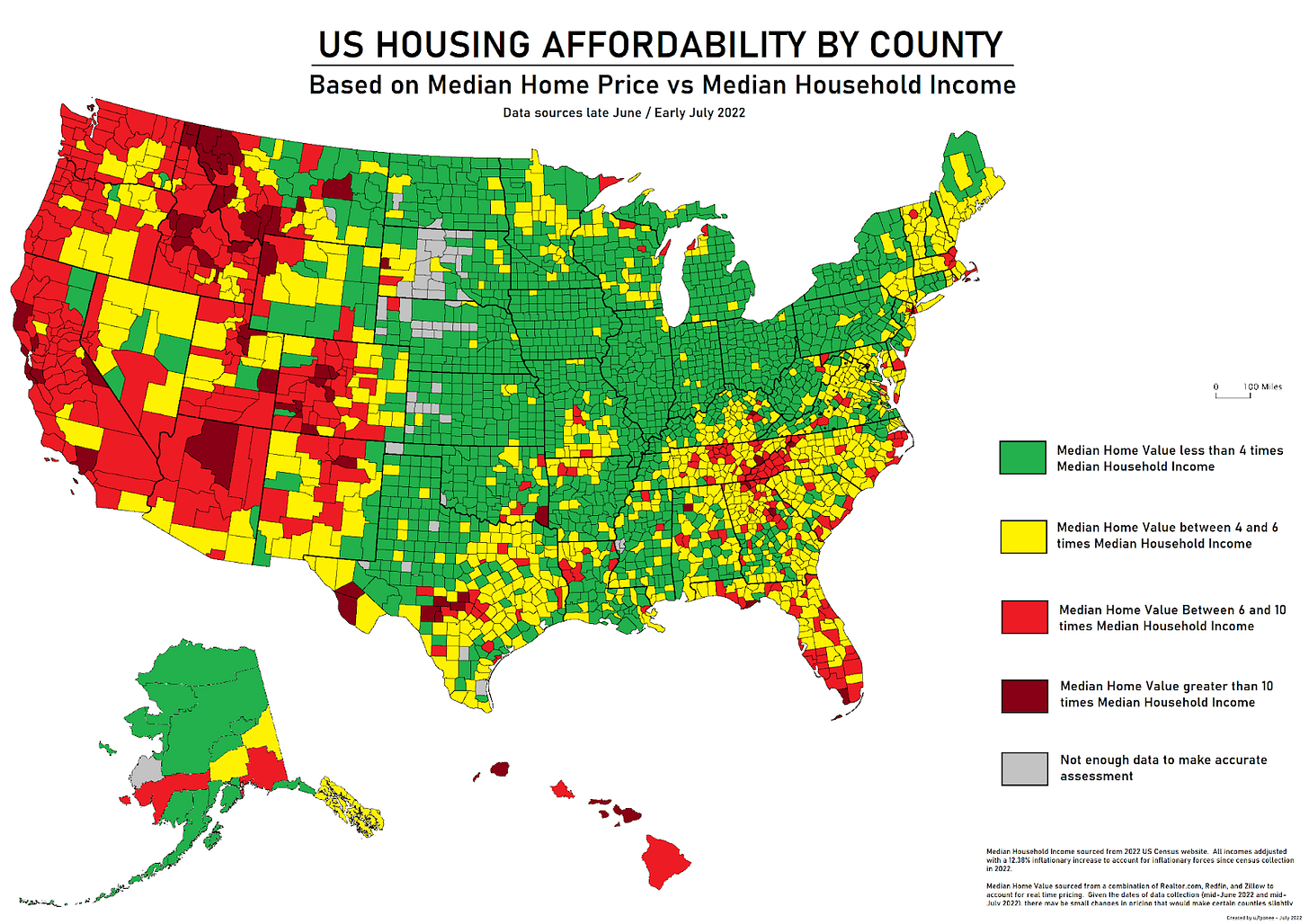

Also on the subject of housing affordability, several years ago a redditor made this interesting map of US housing affordability by county, showing which counties have higher and lower ratios between median home price and median household income.

Maps like this often end up being just population maps in disguise, but this map has another effect superimposed on top of it. In counties with low population but a lot of scenic beauty, median income is probably low but median housing costs are probably high due to the presence of expensive vacation homes. This probably explains the big red blob on the border of Tennessee and North Carolina (home to the Blue Ridge Mountains), and the expensive coastal counties in Florida.

The other very obvious pattern here is how nearly every county west of the Rockies is extremely unafordable. I’m not sure how much of this is due to the above “scenic beauty vs low population” effect, and how much of it is high home prices broadly due to insufficient homebuilding. I can buy home shortages driving up prices in California, but is this really the case in Idaho, Utah, and Arizona?