The Katerra Team Rides Again: ONX Homes

Regular readers of Construction Physics know that I formerly worked for the construction startup Katerra, which raised several billion dollars in venture capital in the hopes of revolutionizing the construction industry, and then went bankrupt. In fact, it was my experiences at Katerra that inspired me to start this newsletter in the first place. Katerra’s collapse became a cautionary tale about overenthusiastic investment, too-rapid scaling, and the hubris of outsiders assuming they could improve industries they didn’t really understand.

But the company’s ignominious ending apparently hasn’t dulled the founders’ enthusiasm for solving the problems of the construction industry. The original Katerra upper management team, including Katerra’s founder Michael Marks, is back with a new construction startup, ONX Homes (pronounced ‘onyx’). Headquartered in Florida, the company has raised around $200 million in investment, and built over 500 single-family homes so far, with another 1,500 in development.

It’s interesting to peek under the hood of ONX Homes, especially in light of its Katerra connection. ONX is doubling down on some features of Katerra that seemed to work the first time, while trying to avoid some of Katerra’s missteps. The founders have clearly learned from the Katerra experience, but they’re also running a different type of business, which will come with its own set of challenges.

From Katerra to ONX

A brief background: Katerra was founded in 2015 by Michael Marks, the former CEO of contract electronics manufacturer Flextronics, which under his tenure became the largest contract electronics manufacturer in the world.1 Like so many companies before it, Katerra attempted to revolutionize the construction industry by applying lessons from manufacturing: rationalize and streamline supply chains, offer “productized” buildings based on standard designs instead of a series of one-offs, and use factory production to construct buildings efficiently. Katerra raised over $2 billion in venture capital from Softbank and other investors, hired thousands of people, and was building factories across the country and around the world.

But Katerra’s reach exceeded its grasp, and the company’s rapid scaling took place before it had found product-market fit. This resulted in a series of painful and expensive pivots, severe layoffs, replacing Marks with a new CEO, a 90% cut in valuation, and, finally, bankruptcy. (Those interested in a longer history of Katerra can read my previous post on the company here.) Now, Marks and much of the original Katerra team are back with a variation on the same basic idea.2

ONX Homes, founded in 2021, is a single-family home building company currently operating in South Florida. The company has chosen what might appear to be an unusual palette of building systems. Instead of using light-framed wood (which most US homes are built from) or concrete block (used in many Florida homes for better wind resistance), ONX builds its homes from precast concrete: that is, concrete pieces cast in a factory and then transported to the jobsite. Walls, stairs, floor slabs, and even foundations are made from precast produced in ONX’s own factories. ONX also uses precast concrete bathroom pods, which arrive from the factory with nearly all the fixtures, finishes and services already installed. Using this system, ONX boasts that it can build a new home in just 30 days.

Unlike most large homebuilders, ONX’s construction process is entirely vertically integrated. It designs the homes, supplies the materials for them, fabricates the components in its factories, and constructs them on-site. And, rather than working with developers, ONX is doing its own development and land acquisition, and selling its homes directly to consumers.

Though right now ONX is only operating in Florida, the company has larger ambitions. A Texas factory is coming online later this year, which ONX plans to follow with factories in California, Nevada, and Arizona. Ultimately ONX aims to serve not only the entire US, but the rest of the world.

The leadership of ONX is, as far as I can tell, all former Katerra leadership. Michael Marks is co-founder and Chairman. The CEO is Ash Bhardwaj, who led Katerra’s Middle East division. ONX President Trevor Schick, COO Ravi Bhat, Chief Design Officer Nejeeb Khan, and co-founder Nic Brathwaite are all also former Katerra top management.

Similarities to Katerra

The ONX team are downplaying their previous efforts at Katerra, but it’s impossible not to make the comparison: much of the Katerra playbook is being run again with ONX.

The most obvious similarity is a focus on factory-built construction. Though Katerra shifted its material palette over time based on the perceived economics (cycling through mass timber, light framed wood, and light gauge steel depending on the day), factory-based construction to reduce costs and increase speed and quality was always the core of its value proposition. And while Katerra’s US operations never really made use of precast concrete, there was a substantial operation in the Middle East that built precast single-family homes, just like ONX is using. ONX is also making use of other technology Katerra chose, such as Framecad CFS machines. Marks and the Katerra team came from a manufacturing background, and still clearly believe that manufacturing and factory-based automation can solve the problems in the construction industry.

However, with both ONX and Katerra, the level of factory construction and automation isn’t quite as high as their marketing suggests. Katerra never successfully deployed high-level of completion wall panels, and construction always required a significant amount of on-site work. Likewise, though ONX talks about factory construction, relatively little besides the bathroom pods gets installed in the factory. The walls are basic concrete sandwich panels with a layer of insulation in them, and much of the work — including services, drywall, and finishes — must be site-installed. Like Katerra, ONX styles itself as a “technology” company rather than a construction company, and goes to great efforts to put the tech company sheen on its operations (emphasizing its use of AI, talking about patents and IP, etc.).

ONX is also following Katerra in its level of vertical integration. Katerra aimed at integrating every part of the construction process: it would design and engineer buildings using Katerra-branded materials, manufacture them in Katerra factories, and build them on-site using Katerra labor and trades. Katerra aimed to be an integrated connection between commoditized material suppliers and developers, and to capture the majority of the value in the process.

ONX appears to be doing something similar. Not only is it doing its own design, manufacturing, and construction, but it appears to have a material supply arm of the company as well. The material and building product brand of Katerra was called Kova, and Kova-branded construction materials are now back in what seems to be part of the ONX effort.3 Kova’s offerings are very reminiscent of what Katerra’s Kova was selling, down to the custom-designed HVAC unit (which was a major Katerra initiative).

But ONX is going even further in its vertical integration than Katerra did. Not only is ONX doing material supply, design, manufacturing and construction, but it's also acting as the developer, acquiring land and selling to consumers. Clearly the team felt that trying to sell “products” to developers was a major drawback to the Katerra strategy.

ONX is also following a similar scaling plan to Katerra’s. ONX is in Florida now, but plans on scaling to Texas, California, Arizona and Nevada next. While Katerra never operated in Florida, its main US operations were in the latter 4 states. Katerra had factories in Texas, California and Arizona, and many of its early projects were in California, Arizona and Nevada.

Differences from Katerra

But while ONX Homes is clearly based on the Katerra playbook, there are some key differences in the two companies.

As we’ve noted, ONX is acting as the land developer, which Katerra never did. Instead of selling its products and services to developers, ONX will sell its homes directly to consumers. This means that despite the surface level similarities, ONX is fundamentally a different kind of business: B2C, instead of B2B.

And though both companies pursued a strategy of leveraging manufacturing and factory-based construction, ONX is focusing on precast concrete, whereas Katerra used a broader palette of building systems, most of which were based on wood. Besides the obvious cost and performance differences, one difference between precast and wood is the level of technical maturity. While both precast and wood framing can be factory-produced at a high level of automation, precast is much more mature, and much closer to a “solved problem.” Highly automated precast plants have been in use for decades and are common throughout the world, while automated light-frame and mass timber manufacturing are somewhat newer, less common, and less “figured out.” Despite ONX’s emphasis on technology and innovation, it’s actually chosen a more conservative building system. This reduces risk, but it also means I don’t expect to see many radical innovations on the building technology side.4

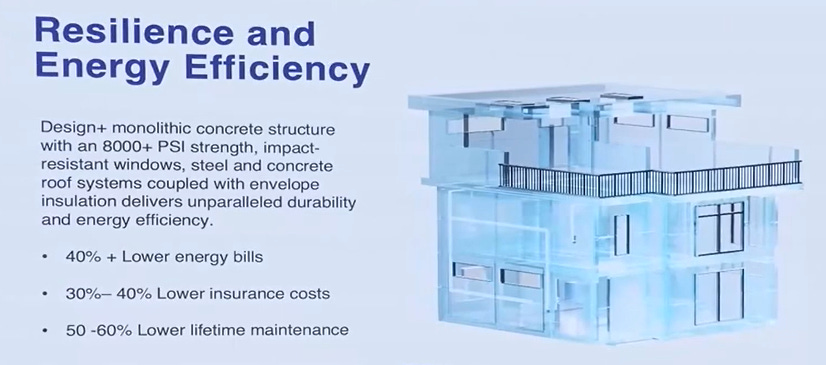

This brings us to another major difference. Katerra was overwhelmingly focused on using factory-built construction to drive cost savings. The company aimed to use economies of scale in manufacturing to produce buildings less expensively than anyone else (“Better, faster, cheaper” was the tagline while I was there). ONX, on the other hand, seems to realize that even with factory construction, it’s unlikely to be able to build homes for cheaper. Current ONX homes are priced in the neighborhood of $200 per square foot (including land).5 While not astronomical, that price certainly does not make ONX the low-cost producer. Indeed, ONX merely claims its homes are “cost competitive” with other homes. Instead, the ONX value proposition is based on greater building speed, more resilient construction, and lowered total cost of ownership. ONX aims to deliver homes that are built faster and are more resilient to wind, fire and other disasters. This resilience, in turn, will lower insurance and maintenance costs. And with a tightly sealed, highly insulated building envelope, and technology like its “AI”-driven HVAC system (whatever that means), energy costs will be reduced as well.

This seems like a reasonable choice for a Florida-based company, where cheap wood construction is already restricted in some jurisdictions, and rising insurance costs are only going to make building with wood more difficult. But it's not obvious how well this strategy will scale to other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Will ONX Homes be successful? The answer to that question is fundamentally also about Katerra and its failure. Was Katerra a basically correct idea that just required some tweaks and evolution? (It’s hard to pivot from mass timber apartments to precast concrete single-family homes if you’ve already built the factories for the former.) Or was the idea fundamentally flawed, with ONX simply being Act Two of a story about failing to understand the construction industry? While ONX has made many alterations to the Katerra strategy (B2C instead of B2B, incorporating land development, building precast single-family homes instead of wood multifamily apartments), at the end of the day they’re both vertically integrated, factory-built construction companies with a focus on material sales.

ONX’s choice of building systems seems unobjectionable (if somewhat unusual for the US), and its goals seem achievable in at least some markets. The major questions will be if the team can reach competitive production costs (their current sales prices don’t tell us much about their actual production costs), and if the value proposition is attractive broadly, or limited to a few geographical markets.

It’s clear that the ONX team has learned from the Katerra experience. Much of ONX seems to be based on redoing what the team felt went well at Katerra (precast homes, material sales) and avoiding what didn’t (trying to sell to developers). While Katerra scaled incredibly rapidly and tried to solve every construction problem simultaneously, ONX seems somewhat more focused; its product offering is narrower, its goals more restrained, and its technology more conservative.

I don’t know if that means they’ll be successful, but the team has bet $200 million so far that they were mostly right the first time.

Though it has now been surpassed by Foxconn and others.

Marks was replaced by Paal Kibsgaard, the former CEO of oil field services company Schlumberger. After Katerra went bankrupt, Kibsgaard and much of the team he brought in started their own Katerra-esque construction company, Symfoni.

From what I understand, Kova and ONX are technically separate companies, but in practice it seems like the same broader effort: job listings for Kova positions indicate that they’re within ONX headquarters and have responsibilities for “coordinating with other ONX verticals.”

If we look past the rhetoric, the main innovations ONX talks about on the building systems side are partnerships with Biomason, which is developing a bacteria-based low-carbon cement, and Hempitecture, which is developing hemp-based insulation. Biomason seems interesting, but right now its product is only being used for some roof tiles. A hemp-based insulated wall panel is interesting (it seems like it will require figuring out how to make hemp into solid, foam-like panels), but won’t yield any fundamental changes in construction costs or how a building goes together.

Though one wonders what their actual costs of production are. Katerra became infamous for pricing its buildings below what it cost to produce them.

If they're not immediately cost-competitive, they're going to have to do one of two things:

1. Get the end consumer to buy into (both metaphorically and literally) the benefits they (supposedly) offer on lifecycle costs.

2. Target the luxury market.

To realize point 1, they are going to *have* to find some way of financializing those cost savings into a form of NPV that can be offered to consumers up front. Running their own insurer and bundling 30 years of (lower-cost) insurance into the sale price so it can be amortized across the mortgage would be extremely risky if their assessments of repair costs and resilience don't pan out, but it's the only thing I can think of off the top of my head.

A similar mechanism could be used to bundle "home warranty" maintenance plans into the sale price at below their market cost. There are ways to financialize basically any long-term cost advantage into net present value, after all.

Point 2 seems quixotic to me, personally, but that's because I'm a cynic. Fashions change faster in the luxury market than down-market and people expect to undertake more frequent renovations for stylistic reasons. I can already envision exactly how much of a copper-plated b**** a "bathroom pod will be to renovate.

Luckily, the presentism the average buyer displays will work in their favor here; if it's fashionable enough today, few buyers will think "what happens when I want to gut the bathroom?" That can be further enhanced if they look to historic, high-value materials which have basically always been in style, like traditional waterproof plaster finishes for bathrooms or marble flooring in the kitchen.

Overall, I doubt they and their investors have sufficient faith in their long-term lifecycle cost savings to embrace the first strategy, and the second is psychologically more feasible. But looking at the floorplans they've built I'm skeptical that's what they're doing.

Precast is, as you noted, a largely mature field; the automation tools embraced in central Europe cost out at rough parity against more labor-intensive models used by US precasters, there's no huge learning curve/scale benefit remaining to find and recover, scale is seriously limited by geography due to shipping costs and challenges... a cynic might suspect Katerra's team understands this but the VC-funded salary is shouting louder than their business sense.

Wouldn't fast built manufactured homes be a better business in emerging markets where countries are urbanising at a rapid clip? You can gain greater economies of scale and often build out an entire neighbourhood in one shot. Or does the lower labour costs in developing countries make the strategy completely uneconomical.