The Long, Sad History of American Attempts to Build High-Speed Rail, Part I

California has received its fair share of criticism for the trajectory of its high-speed rail project. When voters first approved the $10 billion dollar bond issue for the project in 2008, it was projected to be completed by 2020 at a cost of $33 billion. Instead, its costs have ballooned to $128 billion, and the initial segment (which won’t connect Los Angeles and San Francisco), won’t be done until between 2030 and 2033.

But California’s project is just one of a long string of attempts at building high-speed rail in the US. Ever since Japan deployed its first bullet trains in 1964, the US has angled for high-speed trains of its own. But these projects have almost universally failed. In The Second Age of Rail, author Murray Hughes notes that “so many proposals for high-speed railways in the USA have been dreamt up and shot down that it is almost unsporting to list them.” If you go by the International Union of Railways definition of high-speed rail, trains with speed exceeding 250 kmph/155 mph, the US doesn’t have a single high-speed rail line.1

Why have attempts to build US high-speed rail so consistently struggled? What can we learn from the failures? Let’s take a look.

Birth of high-speed rail and first US attempts

High-speed rail first appeared in Japan, with the construction of the Shinkansen (“new main line”) between Tokyo and Osaka in 1964. Built on a wider gauge than Japan’s existing narrow-gauge railways, and without road crossings, sharp curves, or steep gradients, the Shinkansen could achieve speeds of 210 kmph when it debuted, and was soon upgraded to hit 220 kmph. The Shinkansen reduced the travel time between Tokyo and Osaka by more than 50%, from 6 hours 50 minutes to 3 hours 10 minutes.2

Following Japan’s achievement, the US quickly tried to build high-speed trains of its own. These efforts were spearheaded by Claiborne Pell, a Rhode Island Senator known for his “unusual beliefs and behaviors'' (such as wearing a tweed jacket while jogging). An early urbanist, Pell believed that high-speed trains were necessary to build the city of the future, and he drafted the 1965 High-Speed Ground Transportation Act and pushed it through Congress. The act authorized $90 million ($877 million in 2023 dollars) to create an Office of High-Speed Ground Transportation, which would “plan, organize, fund, and evaluate high-speed demonstration projects.”3 A year after its creation, the office (under the newly-created Department of Transportation) signed a contract with the Pennsylvania Railroad to create a high-speed passenger rail route between New York and Washington DC. By using trains capable of going 160 mph, the planners hoped to reduce the travel time to less than 2 hours.4 This route would be followed by high-speed routes from New York to Boston and Philadelphia to Pittsburg. This service would be known as Metroliner.

The Metroliner represented “an attempt by the Americans to build their own bullet trains without incurring bullet train costs”5 (the Shinkansen had cost 380 billion yen, or nearly $12 billion in 2023 dollars). Unlike the Shinkansen, the Metroliner required no new infrastructure construction, running on the same track as existing passenger service (though the rails themselves were upgraded). This allowed development to take place comparatively quickly, in just four years. Perl describes this as the only speed record the Metroliner achieved). But speeding up the project by avoiding infrastructure construction came at a price. Running over track designed for both passenger and freight required frequent, expensive track repairs, and the route was simply “not suitable for sustained high-speed running without major surgery.”6 Because of the track’s unsuitability even after upgrades, Metroliner never achieved its design speeds of 160mph, instead topping out at 120 mph/190 kmph, slower than the Shinkansen. The rapid development period also meant that the cars were extremely buggy, and at any given time 50% of the Metroliner cars would be out of service for maintenance. The ride was known for being extremely rough.

Despite the difficulties, Metroliner service proved popular, making a “modest profit”7 shortly after it debuted, though the Philadelphia-Pittsburgh route never materialized. Metroliner service would continue until 2006, when it was replaced by the Acela.

Shortly after the Metroliner route from New York to Washington was introduced, another high-speed demonstration project, TurboTrains, began to service the New York to Boston route. These trains, designed by the United Aircraft Company, were gas turbine-powered (unlike the Shinkansen and Metroliner, which were electric). Though the trains had achieved speeds of 270 kmph/170 mph in testing (which remains the record for gas turbine-powered rail vehicles), in-service track limitations capped their top speed at 100 mph, and their average speed along the route was only 67 mph. The TurboTrain proved to have even more bugs and ride issues than Metroliner, and TurboTrain service was discontinued in 1976.

Another interesting attempt at high-speed rail in the US during this era was the M497 Black Beetle, an experimental project by the New York Central, mounted two jet engines, intended for use on the B-36 bomber, to a normal diesel railcar. Though it achieved a speed of 295 kmph in testing (still the record for fastest train speed in the US), and was constructed “relatively cheaply,” it was not considered viable commercially.

Despite the success of the Metroliner, it failed to usher in an American era of high-speed rail, and Metroliner service itself quickly deteriorated. Non-stop service between New York and Washington, which achieved a running time of 2.5 hours, was discontinued after 6 months, and in 1971 the Metroliner’s top speed was reduced to 100 mph, where it would remain until the 1980s.

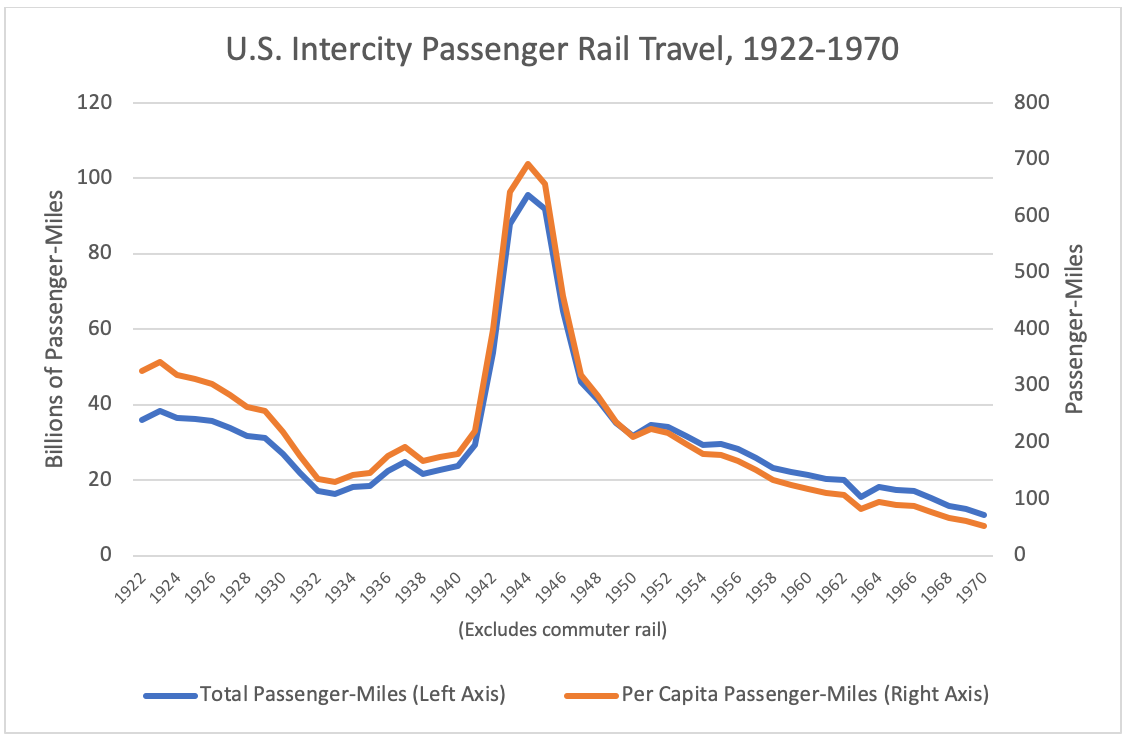

The Metroliner’s difficulties were largely due to the struggles of its parent corporation, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and of US passenger rail more generally. Since the introduction of the automobile, passenger rail traffic had been steadily declining (except for a temporary spike during WWII due to gasoline rationing). Construction of the interstate highway system and the introduction of commercial jet aircraft made things worse. From 1950-1970, passenger rail travel (as measured by passenger miles) declined by roughly 2/3rds.

In an attempt to deal with their financial issues, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central merged (along with the smaller New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad) in 1968 to form Penn Central. But the merger failed to address the companies’ financial problems, and the combined company declared bankruptcy just two years later. It was the largest bankruptcy in US history (eventually eclipsed by the Enron bankruptcy in 2001).

In response to the bankruptcy, the Nixon administration created National Railroad Passenger Corporation, aka Amtrak, to continue passenger rail service. A “quasi-public corporation," Amtrak would operate the passenger rail portions of Penn Central and other bankrupt railroads. The freight portions of Penn Central, along with several other bankrupt freight railroads, were reorganized into Conrail. Any company operating intercity passenger rail could “buy in” to Amtrak, divest its operations, and relieve itself of obligations to provide passenger rail service. Ultimately, 20 out of the 26 rail companies operating intercity passenger rail would do so.

Perhaps predictably, Amtrak immediately struggled financially. The company spent its initial $40 million budget in just a few months, forcing it to request another $170 million from Congress to keep trains running until 1973. Track maintenance had been neglected during Penn’s bankruptcy process, and Amtrak’s shaky financial footing (operating losses went from $158 million in 1973 to $570 million in 1977) resulted in its infrastructure continuing to deteriorate. By 1979, Amtrak’s rail cars were “relics," with more than 75% of them averaging 28 years old, and the on-time arrival rate of its trains was just 57%. With it a struggle to simply keep its services operational, Amtrak building a high-speed rail service wasn’t in the cards. In fact, its one high-speed rail service, the Metroliner, got worse: “schedules were lengthened as tracks deteriorated.”8

In an attempt to deal with Amtrak’s issues, in 1976 Congress passed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act, which authorized $1.75 billion in funding for Amtrak to improve service in the Northeast corridor (known as the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project, or NECIP). The act required, among other things, for Amtrak to offer 2 hour 40 minute service between New York and Washington, and 3 hour 40 minute service between New York and Boston within 5 years, and to begin developing even faster service. But due to poor planning and project management on Amtrak’s part, costs ballooned and the project fell behind schedule. By 1979, a GAO report concluded, “The project will not be completed until the end of 1983 (1984 in the Boston area) and the shorter travel times will not be achieved within the $1.75 billion authorized.” By 1985, the NECIP was still only 95% complete, and it had failed to achieve its speed goals for the Metroliner. Increasingly, it was looking like Amtrak would not be the company to bring high-speed rail to the US.9

In response to Amtrak’s failures at the federal level, smaller, state-level high-speed rail efforts began to appear. One early attempt came from Ohio, which had been planning its own high-speed rail project as far back as 1972. That year, Ohio Senator Robert Taft called for “a network of high-speed trains to be built and operated apart from the federal government,”10 which resulted in a study of high-speed rail done by the Ohio General Assembly staff. In 1975, Ohio state legislator Arthur Wilkowski, who had become “disenchanted with Amtrak," campaigned for a series of high-speed rail routes across the state, declaring “we will build this system in the ashes of Amtrak.”11 By 1980, the Ohio Rail Transportation Authority was planning a “150 mile per hour electrified, state of the art high-speed railroad.” At the time, Ohio’s economy was suffering from the loss of manufacturing jobs, and lawmakers hoped that a high-speed rail program could stimulate its economy and that “Ohio [could] become the center for high-speed rail passenger technology in the United States”:

As interest grows in other states for similar service (as it undoubtedly will) Ohio companies could sell the expertise, equipment, and technology they developed. Ohio already possesses an outstanding industrial base with the necessary infrastructure and skills to meet the requirements of the high-speed rail technology. Whether it be steel, vehicle construction, or sophisticated electronic controls, it is, or can be, made in Ohio.12

Ohio’s plans faltered, however, when a 1982 ballot measure that would create a 1 cent sales tax to fund the $8 billion projected system cost failed to pass. The measure was defeated by such a wide margin (roughly 75% of voters voted against it) that not only did it kill Ohio high-speed rail, but it made other states reluctant to try to develop publicly financed high-speed rail systems.

Another state-level attempt at high-speed rail came in California. In 1980, a group of Amtrak executives “left the corporation to pursue rail renewal efforts that seemed beyond Amtrak’s grasp,”13 and formed a sort of Amtrak spinoff, the American High Speed Rail Corporation (AHSRC). Funded by Japanese rail companies (and a loan from Amtrak), the AHSRC planned to use Japanese bullet train technology to build a high-speed rail route between Los Angeles and San Diego. The projected $2.9 billion cost would be funded by a combination of bonds issued by the State of California and private investment. The project was endorsed by the governor, and legislation authorizing the bonds was quickly passed. The California treasurer joked that “if the train is half as fast as the legislation passed for it, it would be a huge success.”14

But the project generated opposition just as quickly. As the proposed ridership figures came under scrutiny, critics claimed they were inflated to the point of being “virtually fraudulent,”15 an accusation exacerbated by the AHSRC’s refusal to release the full version of the ridership study. The AHSRC’s behavior fueled worries that the project would ultimately require more government funding to fill in the gaps. The AHSRC also attempted to get around complying with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), but it soon became clear that this would result in an unacceptable political backlash, forcing the project to complete an expensive environmental impact assessment. Ironically, trying to get around CEQA may have resulted in the worst of both worlds, as the project was both opposed by environmental groups and had to comply with burdensome environmental regulations. The AHSRC proved to be insensitive to resident complaints, taking an “adversarial stance against its critics”16 and dismissing them as selfish NIMBYs. A writer for Passenger Train Journal noted that “AHSRC from the outset essentially told Southern Californias what it was going to do for them, rather than asking what people wanted.” The project was killed in 1984 when AHSRC failed to raise $50 million from investors, who were unwilling to pay for the required environmental impact assessment.

Given the California and Ohio failures, high-speed rail faced a troubling “policy inheritance.”17 Both cases implied that while public funding for high-speed rail projects would be difficult to obtain, projects would still be required to meet the environmental and planning standards of government projects.

While the AHSRC attempted to build high-speed rail in California, a similar attempt was struggling in Florida. In 1980, the Florida governor established a committee to study high-speed rail for Florida, and in 1984 the state legislature passed the Florida High Speed Rail Transportation Commission Act, which created a commission to evaluate private proposals to create state high-speed rail. Two applications were received in 1988 from the Florida High Speed Rail Corporation and the Florida TGV Company to build high-speed rail routes from Miami to Orlando and Tampa, but “after 2 years of review it became apparent that further pursuit of a franchise under the conditions established was futile.”18 Both companies had hoped to fund the project by taking advantage of increased land value that would result from the route's construction, but local governments opposed increased development along rail routes. Florida TGV withdrew its application after it became clear that the government would not provide any public funding for the project, and Florida High Speed Rail Corporation withdrew it’s after the governor rejected it as too costly.

Though the US was one of the first countries to attempt high-speed rail following Japan’s debut, by the end of the 1980s it was rapidly falling behind. Though the Metroliner was achieving speeds of 120 mph, this was far less than the Shinkansen’s 170 mph, and Japan was quickly being joined by other countries. In France, the TGV, first built in 1981, was achieving speeds of 186 mph by 1990, and Germany, Italy, and Spain were building or had built their own high-speed rails systems.

But rather than giving up, America would tackle a host of new attempts to build high-speed rail in the 1990s.

This series will conclude next week with Part II.

Sources

Itzkoff (1985) - Off the Track: The Decline of the Inner-city Passenger Train in the United States

Hughes (1988) - Rail 300: The World High Speed Train Race

Hughes (2015) - The Second Age of Rail: A History of High-Speed Trains

Perl (2002) - New Departures: Rethinking Rail Passenger Policy in the Twenty-First Century

Albalate and Bel (2014) - The Economics and Politics of High-Speed Rail

Vranich (1991) - Supertrains: Solutions to America’s Transportation Gridlock

Vranich (1997) - Derailed: What Went Wrong and What to do About America’s Passenger Trains

GAO (2009) - High Speed Passenger Rail: Future Development Will Depend on Addressing Financial and Other Challenges and Establishing a Clear Federal Role

This definition is somewhat complicated. The IUR apparently relaxes this definition in some cases, considering speeds of 200/220 kmph on upgraded lines to constitute high-speed rail. The US confusingly also uses a different, more expansive definition of high-speed rail. HSR-Express is “top speeds of 150 mph on grade-separated, dedicated rights of way.” HSR-Regional is “top speeds of 125–150 mph, grade-separated, with some dedicated and some shared track.” Under the US definitions, both the Acela and the recently constructed Brightline would qualify as high-speed rail. If and when the Acela gets upgraded to achieve 160 mph maximum speeds, it would meet the IUR definition of high-speed rail.

Notably, this would not meet the modern definition of high-speed rail.

Perl 2002

There’s some conflicting information here. Rail 300 (p34) says 2 hours, while New Departures (p141) says 3 hours.

Hughes 1988

Hughes 1988

Perl 2002

Vranich 1997

The next administration became increasingly hostile to Amtrak. A 1981 bill that would dedicate $2 billion to Amtrak to build high-speed rail in 20 corridors failed to pass, and Reagan “declared war on Amtrak’s subsidies” (Perl p151).

Vranich 1991

Vranich 1991

Perl 2002

Perl 2002

Perl 2002

Perl 2002

Perl 2002, Vranich 1997

Perl 2002

Perl 2002

High-speed rail is a niche product that is not viable in most countries. For the product to work there must be ample distance between stations - what is the point of accelerating a train to 200mph if it needs to stop in 15 minutes at another station? However, the further stations are separated, the more inconvenient it is to access the train. And how does one access the train? If one has a car then it very quickly becomes more convenient to drive to ones destination than to drive to a rail station to take a train to another rail station and then figure out how to get to where one actually needs to go. And once destinations are more than several hundred miles apart flying becomes the competitive option.

In the US not only is driving more convenient but taking the bus or shuttles between cities is more convenient than taking a train. One of the bizarre biases for trains is that buses and shuttles are discredited by the professional class. Along the I-95 corridor between DC and Boston this is especially odd since the train is no faster than the bus and taking the bus can be far less expensive!

At a certain level it is understandable how Americans romanticize trains and discredit highways. What is inexplicable is the ignoring of air travel as a good solution for fast, convenient, medium distance travel. Seems one reason we don't have "flying cars" is the experts and policymakers are too busy trying to make fast trains work where they will never be useful.

The last time I took a train was in 1974, from SF to Portland, OR. It took 22 hours. I can drive it in 11 hours. The biggest problem trains have competing with air travel is construction and maintenance costs. Trains require track for every inch of the route; aircraft need a couple of miles of runway at each end of the flight, and in between they move on air, with is free and self-repairing after each plane's passage. That said, the US could have built high-speed rail networks spanning the entire continent for the $6 trillion we blew over the last two decades on Middle East wars, and the 5,000 service personnel who died there would still be alive if they had been construction workers instead. I guess the Military-Industrial Complex lobby is more persuasive than the high-speed rail lobby.