The Surprisingly Long Life of the Vacuum Tube

The last several decades of technological progress have, in large part, been about finding more and more things we can do with semiconductors and the technology for producing them. Microchips have found their way into virtually every car, aircraft, appliance, and electronic device. Light-emitting diodes are steadily replacing older, less efficient methods of generating light (such as incandescent bulbs). Solar photovoltaic panels have become the most rapidly deployed energy source in history. Semiconductor lasers have enabled fiber-optic communication. Semiconductor-based charge-coupled devices (CCDs) and CMOS sensors are used for digital imaging. The list goes on.

But decades before the invention of the transistor, another enormous technological ecosystem was built around a device that manipulated the flow of electrons — the vacuum tube. In the first half of the 20th century, vacuum tube technology found its way into all manner of devices, from radios to TVs to the earliest computers. And like semiconductors today, vacuum tubes had applications far beyond electronic logic — the phenomenon they leveraged could be applied to everything from lighting and displays to video cameras and radars. And while the vacuum tube feels like an ancient technology that has long been superseded, much of the technological edifice still stands.

Origins of the vacuum tube

A vacuum tube is an evacuated tube (often, though not always, made of glass) containing electrodes, between which electrons flow. These tubes, along with various offshoots and technological cousins, were the product of two parallel strands of development.

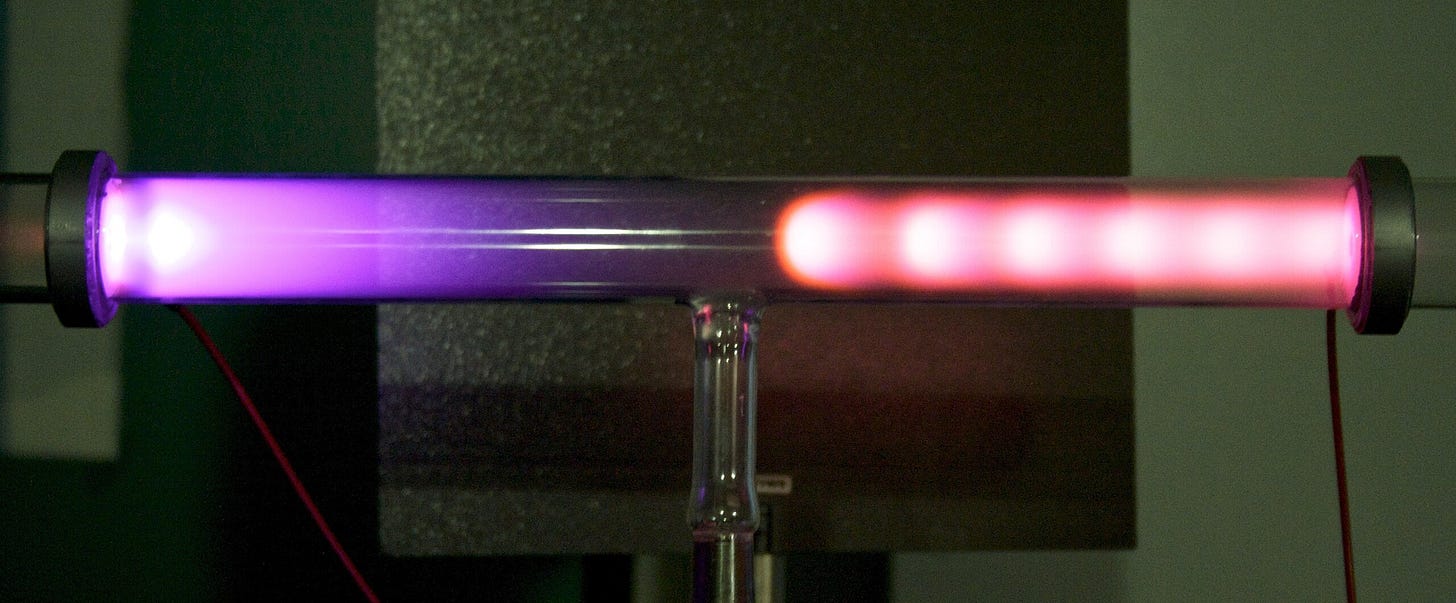

The first line of descent was via what are known as “gas discharge tubes” — tubes where electricity is discharged through a highly rarefied gas (gas at very low concentration and pressure). Not long after the German scientist Otto von Guericke invented the first vacuum pump in 1650, early scientists began using such pumps to study highly rarefied gasses. It was observed that running an electric current through rarefied gasses could make them glow colorfully, but for many years this was mostly regarded as an interesting curiosity.

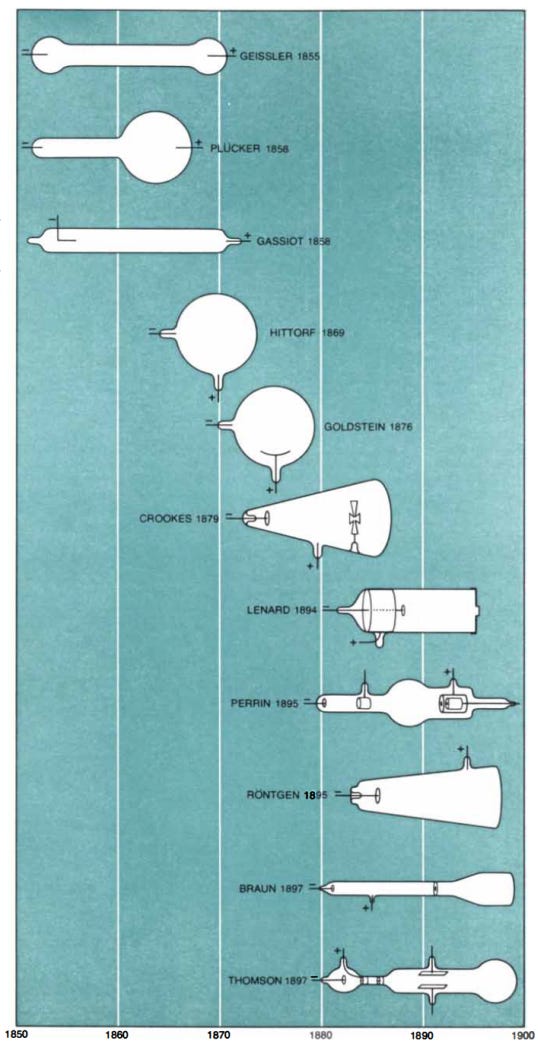

It wasn’t until the 1830s, with the experiments of the English chemist and physicist Michael Faraday, that the effects of electricity on rarefied gasses began to be studied more seriously. Faraday subjected a variety of rarefied gasses to electric current, observing their colorful glow, along with a curious “dark space” between the two electrodes. Faraday was a well-regarded scientist, and others took notice of his work: in 1855, Julius Plücker, a German scientist who “idolized Faraday”, endeavored to replicate Faraday’s experiments. To perform the experiments, Plücker obtained some highly evacuated glass tubes from the well-known instrument maker Heinrich Geissler. Geissler had built a vacuum pump capable of achieving a far lower vacuum than any pump previously, and Geissler’s tubes could function over a range of temperatures thanks to their platinum lead-in wires. (Platinum has nearly the same coefficient of thermal expansion as glass; several decades later, Edison would use the same strategy of platinum lead-in wires for this first incandescent light bulb.) These would later be known as “Geissler tubes”.

By using a series of well-crafted, highly evacuated glass tubes “of ever-escalating complexity”, Plücker followed Faraday’s footsteps in investigating the behavior of electrical discharge through highly rarefied gasses. During his experiments, Plücker observed what appeared to be some sort of emanation from the negative electrode (cathode). These emanations moved in a straight line, could be deflected by a magnetic field, and caused the wall of the tube near the positive electrode (anode) to glow green. Other scientists, including William Crookes and Plücker’s collaborator Johann Hittorf, investigated these emanations further, and they eventually came to be known as “cathode rays”. The tubes used to study cathode rays began to be referred to as “Hittorf tubes” or “Crookes tubes”, and proved to be an important scientific instrument for studying the nature of matter. In 1895, the German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen, using a Crookes tube to study cathode rays, stumbled upon X-rays, for which he would be awarded the first Nobel Prize in physics in 1901. In 1897, the British physicist J.J. Thomson discovered that cathode rays were actually streams of negatively charged particles — which were dubbed ‘electrons’ — for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1906.

The other line of development for vacuum tubes was via incandescent lights. In 1802, the British scientist Humphry Davy created an incandescent light by connecting a thin strip of platinum to a “battery of immense size”, and over the next several decades more than a dozen scientists and inventors tried their hand at creating an incandescent light by enclosing a filament in a glass bulb containing a vacuum or inert gas. But it wasn’t until 1879 that a practical incandescent bulb was invented, simultaneously by Thomas Edison in the US and Joseph Swan in the UK. Edison’s success was in large part due to achieving higher levels of vacuum than had previously been possible, obtained by way of a highly modified Sprengler mercury vacuum pump, first invented in 1865.

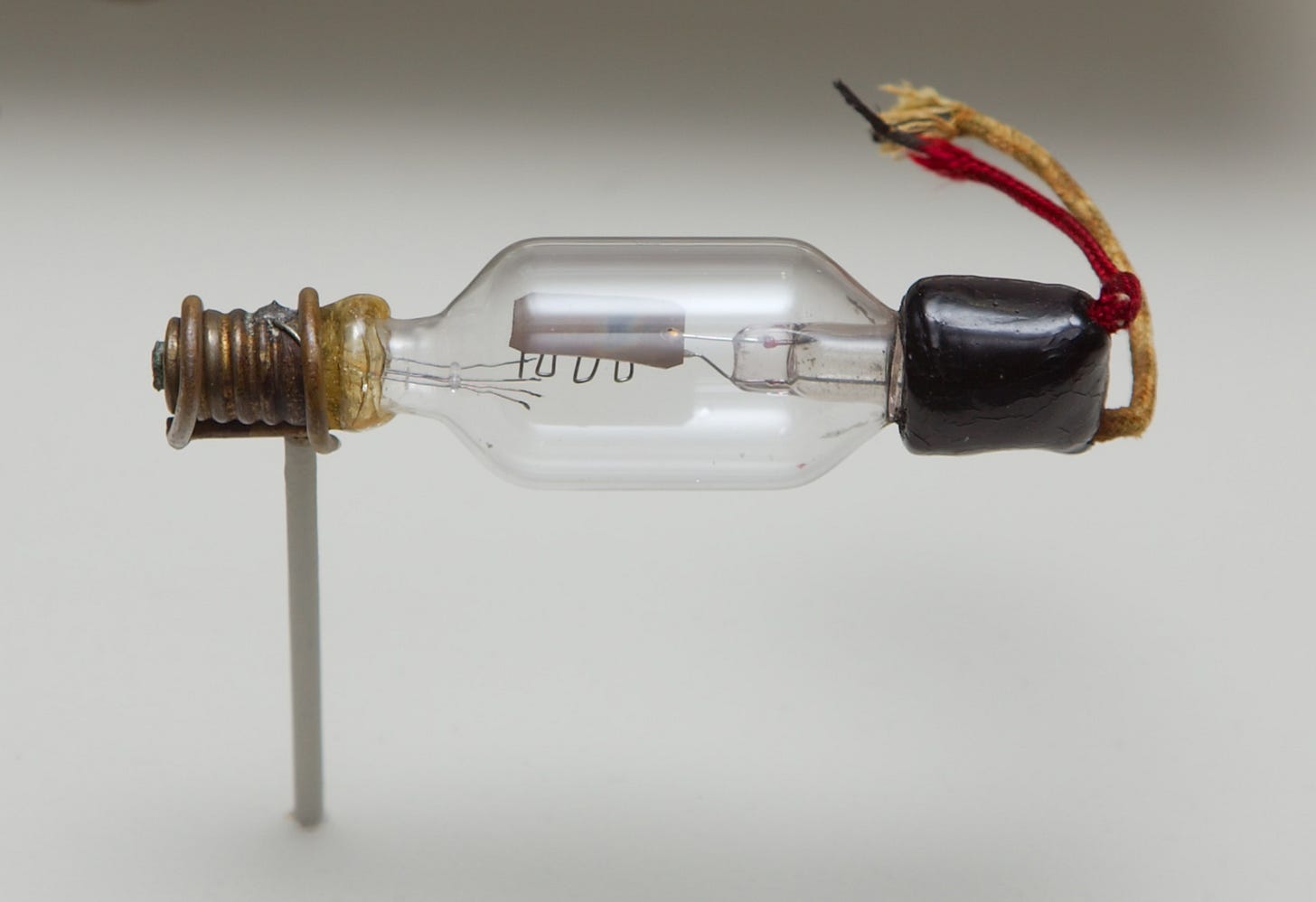

Early incandescent bulbs had the tendency to gradually blacken on the interior, reducing the light emitted and eventually rendering the bulb unusable. While studying this phenomenon in the hopes of eliminating it, Edison placed a small metal plate within the bulb of various lamps. It was eventually discovered that electric current was unexpectedly flowing from these metal plates, a phenomenon that Edison modestly dubbed “the Edison Effect”. (Today we know this current is due to thermionic emission, electrons being ejected from the hot light bulb filament.)

The rise of the vacuum tube

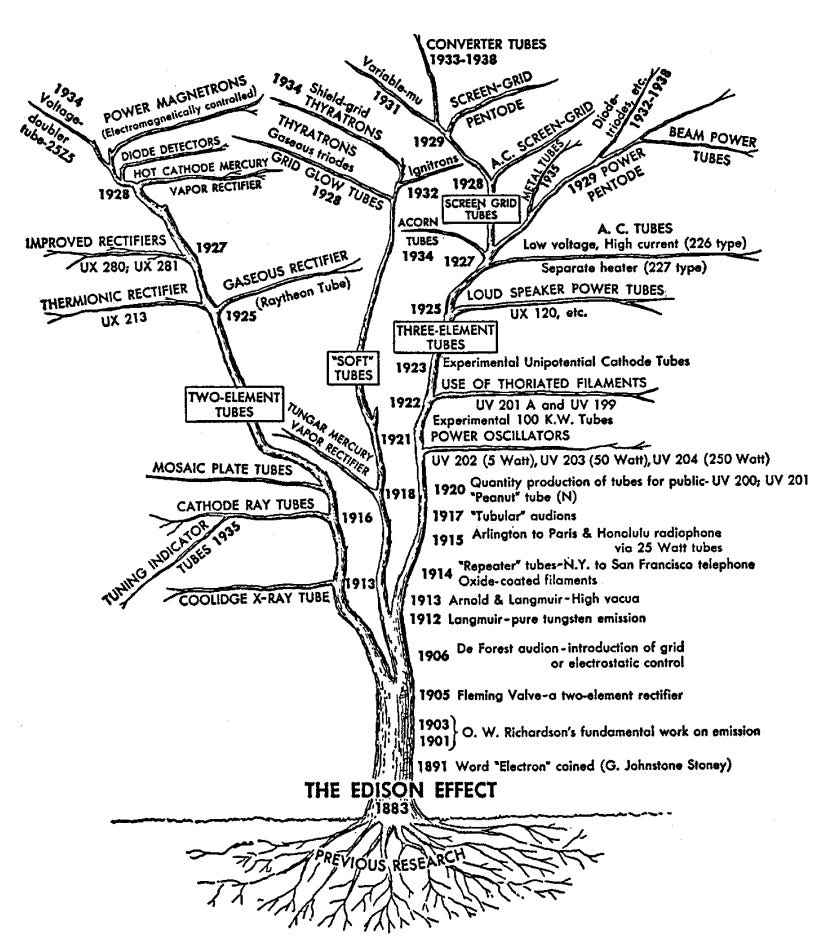

By the turn of the 20th century there were two types of devices — Crookes tubes and other similar gas-discharge tubes, and experimental Edison Effect lamps — in which electrons flowed between electrodes within a highly evacuated glass tube. Over the next several decades, these two devices would spawn a broad array of vacuum tube technology.

In the 1880s, British scientist and engineer John Fleming began studying the Edison Effect, and discovered that electric current could flow from the hot filament to the metal plate but not vice versa. In 1904, Fleming used this phenomena to build the Fleming Valve, a vacuum tube which acted as a rectifier converting alternating current into direct current in early radios. Not long after, American inventor Lee de Forest, in the course of trying to invent an improved radio signal detector, added a third element — a metallic grid — between the cathode and the anode in a Fleming valve.

De Forest eventually discovered that by changing the voltage in the metallic grid, the flow of electricity from the cathode to the anode could be controlled, allowing the device to act as an amplifier. De Forest had little idea how his device (which he dubbed “the Audion”) worked: he thought, incorrectly, that it relied on the flow of charged particles of gas within the tube. But when he offered the Audion to AT&T, the company’s scientists and engineers recognized its potential.

AT&T studied the Audion, working out a theory for how it behaved, and turned it into the more useful and reliable triode vacuum tube device. Triodes made the first transcontinental telephone lines (first demonstrated by AT&T in 1915) possible, and spawned a panoply of related vacuum tubes — four-element tetrodes, five-element pentodes, and so on. Radios, which were exploding in popularity in the early 20th century, were one of the largest use cases of these vacuum tubes, but they were also used in telephone equipment, televisions, and in the first digital computers. By the late 1920s, AT&T was using over 100,000 vacuum tubes in its telephone system. ENIAC, one of the first programmable general purpose digital computers, was powered by 18,000 vacuum tubes, mostly dual triodes — two triodes in one glass envelope.

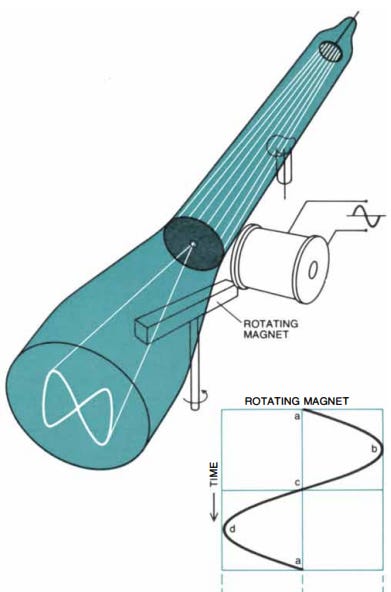

In 1896, the same year that the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi demonstrated his radio to British Post office officials, the German physicist Ferdinand Braun was looking for a way to measure the waveforms of alternating electrical current — current which changes its direction of flow through a circuit periodically. Some high-frequency alternating currents alternated back and forth thousands of times per second, so fast that any recording device that worked by moving a physical object back and forth couldn’t keep up. But Braun suspected that cathode rays could be used to make a measuring device for these high frequency currents. If the rays were made to pass through a narrow opening, the glowing spot on the tube would be reduced to a small point. And by using a magnetic field, the path of the beam could be deflected, moving the point of illumination and drawing the shape of the current’s waveform. Because a beam of cathode rays had virtually no intertia, it would be able to respond to changes in an electrical current (which would induce changes in the magnetic field) almost instantly. With the help of Franz Müller (an instrument maker who took over Geissler’s firm following Geissler’s death), Braun had several experimental tubes fabricated, and used them to study the behavior of high-frequency alternating currents, publishing his first paper in 1897. Braun called his device a cathode ray indicator tube.

Braun tubes (more commonly referred to as “cathode ray tubes”) became widely used to create electronic displays. Oscilloscopes — devices which show the voltage of a circuit graphically — are directly descended from Braun’s cathode ray indicator tubes, and in the 1920s cathode ray tubes became the basis for the first television. Inventor Vladimir Zworykin’s television system used a specialized cathode ray tube as a video camera to record an image, and another cathode ray tube to display it. (A parallel television inventor, Philo Farnsworth, used a cathode ray tube for the TV screen but a slightly different vacuum tube technology for the camera.) Both cathode ray-based video camera tubes and television screens would be the primary television technology for the next several decades, until they were succeeded by flat-panel displays and semiconductor-based cameras.

In the 1920s, cathode rays saw a number of other uses, including building the first electron microscopes. Cathode ray tubes were also used as an early form of computer storage (known as storage tubes or Williams tubes) until they were supplanted by superior memory technology (such as magnetic core memory).

The gas discharge tubes that spawned Braun’s cathode ray tube also found numerous other applications. In the 1860s, French engineer Alphonse Dumas and doctor Camille Benoit built the Ruhmkorff lamp, a gas discharge lamp using a Geissler tube connected to a battery-powered induction coil. In the 1890s American inventor Daniel Moore devised his own Geissler tube-based lighting system, known as the Moore Lamp. But it was the discovery of the noble gas neon in 1898 which truly made gas discharge lighting popular. Georges Claude, a French engineer and co-founder of the company Air Liquide, was producing large amounts of neon as a byproduct of air liquefaction, and in 1910 displayed a neon light based on a gas discharge tube filled with trace amounts of neon. Other popular lighting technologies — mercury vapor lamps, fluorescent lamps, sodium vapor lamps — were also gas discharge tubes containing different types of gas.

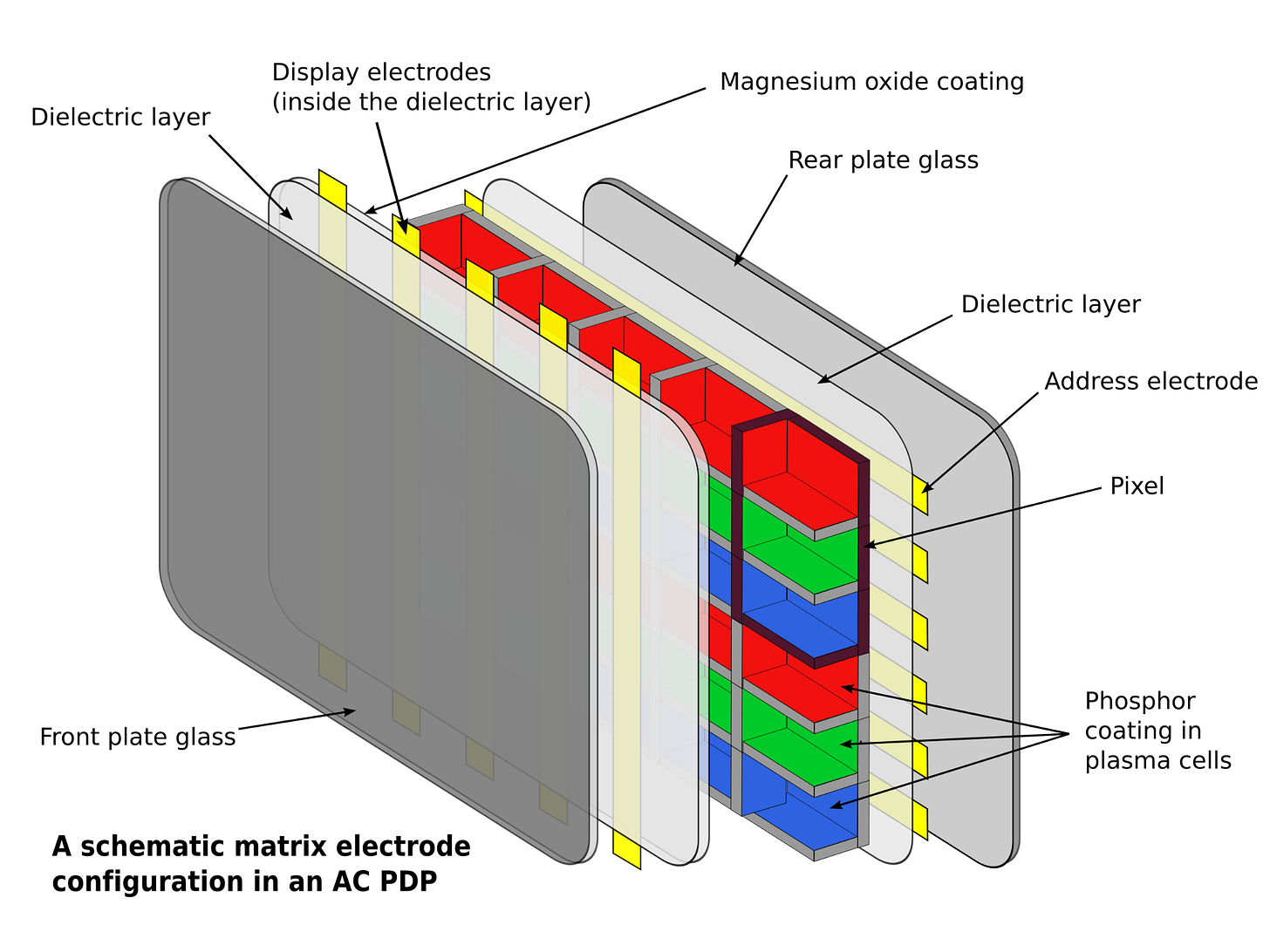

And the gas discharge tube had many applications beyond merely providing lighting. Thyratrons, invented in the 1920s, are gas-discharge tubes that work similarly to vacuum tubes but can handle much higher currents. The pixels on a plasma TV are made up of millions of tiny gas discharge tubes. Gas discharge tubes are used to build, among other things, carbon dioxide lasers, Geiger counters, and surge protectors.

Gas discharge lamps generate light (a type of electromagnetic radiation) by using electric current to excite gas molecules within the tube. But vacuum tubes could also be used to generate other sorts of electromagnetic radiation. As we’ve noted, Wilhelm Roentgen accidently discovered that a Crookes tube generated X-rays in the 1890s, and today, modern X-ray machines still use vacuum tubes to generate X-rays. In the 1920s, researchers at General Electric invented the magnetron, a vacuum tube originally conceived as an electronic switch, but which was later discovered could generate microwaves. An improved version of the magnetron developed by the British during WWII, the cavity magnetron, made aircraft-mounted microwave radar possible, becoming one of the most important inventions of the war. Following the war it was discovered that magnetron-emitted microwave radiation could be used to heat food, and magnetrons are still found in microwaves today. The Klystron, another powerful tube-based microwave emitter, was invented by the American engineers Russell and Sigurd Varian in the 1930s, and found a wide range of uses: Klystrons provide power for particle accelerators like Stanford’s SLAC, are the heart of radiation therapy machines for cancer treatment, and are used for things like food scanning and medical sterilization. Gyrotrons, vacuum tubes which can generate even higher-frequency radiation, are used to heat the plasma in fusion energy experiments.

Beyond their use in particle accelerators and fusion energy experiments, vacuum tube-based devices were powerful instruments for enabling scientific research. Four Nobel Prizes were the product of vacuum tube devices (five if you include Irving Langmuir’s research on incandescent light filaments, which netted him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932.) In addition to the ones we’ve already mentioned — Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays, J.J. Thompson’s discovery of the electron — Ernst Ruska won the 1986 prize for his work on the electron microscope, and Owen Richardson won the 1928 prize for his studies of thermionic emission. And the indirect impact of vacuum tubes on science was likely larger still. Vacuum tube devices powered numerous scientific instruments, and investigation into the behavior of vacuum tubes spawned a line of research that resulted in the discovery of electron diffraction, and Bell Labs’ first Nobel Prize.

Conclusion

In my book I describe technological progress as a series of overlapping S-curves. A technology comes along, improving slowly at first and then more rapidly, eventually reaching some performance ceiling after which it gets replaced by some successor technology which is on its own, higher-baseline S-curve. And while I think at a high level this is correct, it fails to capture the Cambrian explosion that can follow some new technology coming into the world. The vacuum tube wasn’t a single device, but an entire panoply of devices that used the same basic principle — electrons being emitted off of a cathode — in a variety of different ways. These devices all advanced along their own S-curves, improving at different rates and plateauing at different times. Many of them have since been supplanted by successor technologies (often based on semiconductors, another broad category of device with many specific implementations), but many of them — magnetrons in microwaves, gas discharge tubes in gas lasers, gyrotrons in fusion energy experiments — remain in use today.

Vacuum tubes have another specific modern use: in amplifiers, where their non-linear behavior at higher temperatures can create everything from a "warm" sound (with added harmonics) to the "distorted" sound associated with electric guitars. Musicians pay extra for vacuum-tube amplifiers. Even technologies that fall out of widespread use can still have artistic uses or even become luxury products.

Small correction:

> by changing the current in the metallic grid

Umm, no. The voltage of the grid, relative to the cathode, blocks the electrons (or not).

The small(ish) current from the cathode to the grid the does flow when the tube conducts is secondary.