How a Government Think Tank Trained The First Generation of US Software Developers

The US government had a hand in creating much of the early computer industry. Many early computers, such as ENIAC and EDVAC, were developed with government funding for military purposes (ENIAC was used to calculate artillery firing tables). It was the government-granted monopoly of AT&T where the first transistor was invented, and for years after its invention the US military was the largest purchaser of transistors. It’s perhaps not surprising then, that the government also had a major role in training the first generation of software developers.

Software and SAGE

Following the end of WWII, the Soviet Union quickly emerged as a major potential threat to the US and western Europe. In 1946 Winston Churchill delivered a speech where he declared an “iron curtain” had descended across Europe, and advocated for Anglo-American cooperation to counter Soviet influence. By 1949, Germany had officially been partitioned into East and West Germany, and the Cold War was underway.

That same year, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb, creating the possibility of a devastating Soviet nuclear attack on the US by bombers flying over the north pole. Intercepting such an attack required detecting the bombers as early as possible, but the US’s existing air defense system, which relied on slow, manual processing of radar station data, couldn’t respond quickly enough. A committee organized by the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board, known as the Valley Committee, recommended upgrading the entire US air defense system with better interceptors, missiles and anti-aircraft guns, and extensive radar coverage. It also recommended a computer-based command-and-control system to rapidly process and coordinate air defense system data.

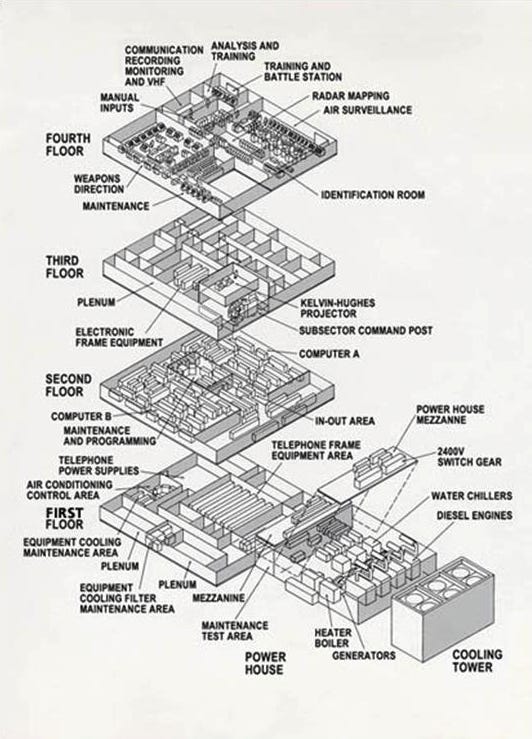

In 1950, MIT was contracted to create a prototype for the computer-based air defense system, using MIT’s in-development Whirlwind computer, the only computer in the world that could process incoming data in real-time. In 1954, the Air Force decided to proceed with the full-scale computerized defense system, known as the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, or SAGE. SAGE would use computerized data processing to coordinate many radar stations across the country, creating “a single unified image of the airspace over a wide area”.

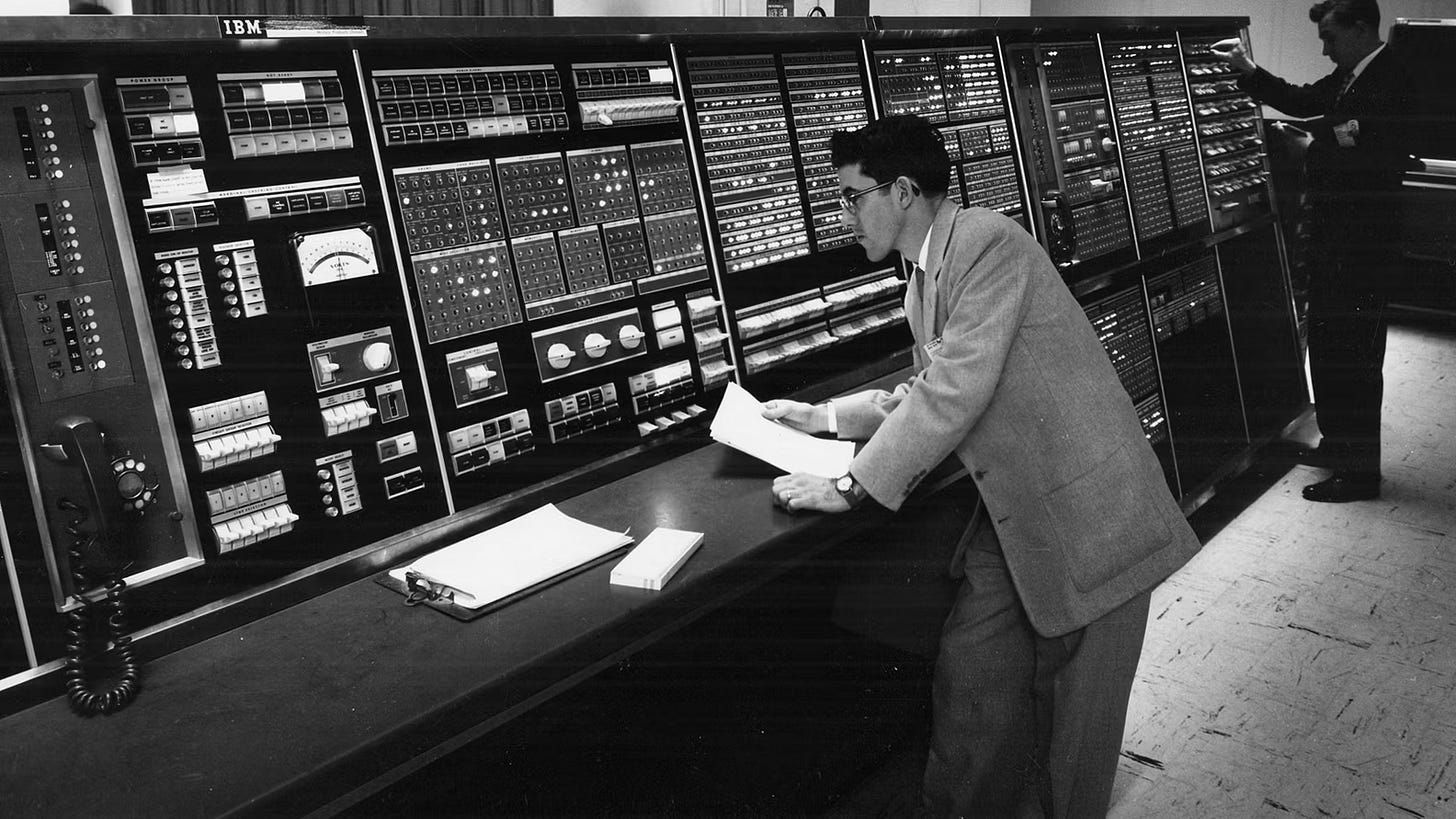

IBM was awarded the contract to build the computers for 24 SAGE sites around the country. Based on the Whirlwind, the enormous AN/FSQ-7 computers weighed 250 tons, consumed 3 megawatts of power, and contained 49,000 vacuum tubes. In terms of physical dimensions, the AN/FSQ-7 computers were, and are, the largest computers ever built.

IBM built the computers, but making SAGE work also required creating the software to run the system. IBM declined the offer to program the SAGE software, on the grounds that it “couldn’t imagine” how it could absorb the estimated 2000 programmers the job might require once the job was done. MIT and Bell Labs similarly declined.

The Air Force thus turned to the RAND corporation, a non-profit think tank created in 1948 to try and maintain the “vast amount of American scientific brainpower assembled to fight World War II.” At the time, RAND was engaged in a study of group performance of “man-machine” systems: it had created a replica of an air defense radar station to study how its operators behaved under stress, and how their performance could be improved. Making this system work required large amounts of computation to create the simulated radar data for enemy aircraft:

For a typical eight-radar exercise, each 100-minute period required 1,600 such computer-produced “‘displays,” as well as eighty time-phased teletype messages and numerous closely coordinated maps, lists, and scripts. Some eight hundred flights were specified for each exercise, resulting in 80,000 punch cards produced in 1,500 hours of manual and computer calculations. From the resulting track library, the actual inputs for each exercise, some 10,000 cards, were machine-produced in twenty-five hours. - The System Builders

RAND’s radar operator performance studies made it an obvious candidate for programming the SAGE system. Not only was RAND already working on the problem of processing radar station data, but to do so it had already hired a substantial fraction of the programming talent in the US. In 1955 RAND employed 25 programmers, at a time when there were only an estimated 1200 programmers in the entire country, only 200 of which were creating programs of substantial complexity. In 1955 RAND agreed to take on the task of programming for the SAGE system, and by the end of the year 75 people at RAND’s System Development Division were working on SAGE.

Programming SAGE was vastly more complicated than any software task that had preceded it. One SAGE programmer noted that when he was hired, “large programs were about 25 steps”, and that he was taken aback when one older programmer claimed to have written a 300-instruction program. But a single SAGE program might have as many as 800 instructions, and the entire SAGE system ended up having more than 1 million instructions. Initially RAND had estimated that programming SAGE might require 100 programmers, but it soon became obvious this was a gross underestimate. By 1956 RAND had hired so many programmers and other staff to work on SAGE that the staff of the System Development Division was greater than the rest of RAND combined, and the division was spun out as a separate entity, the System Development Corporation, or SDC. By 1959 SDC had 800 programmers working on SAGE, and it’s estimated that SDC employed half of the programming manpower in the US.

Because of how nascent computers, and computer programming, was, hiring the number of programmers SAGE required wasn’t straightforward. Part of the interview process was asking whether candidates knew what computer programming was, and one hired programmer noted that “most of us didn’t know what a programmer was until we came to work at SDC”. In the absence of experienced programmers, SDC recruiters looked for “good logical minds and a math or science background”, but it proved hard to predict who would end up being an adept programmer. Hired candidates were given four months of training (two on the IBM computers, and then another two on the SAGE system). Nearly 90% of those hired were between the ages of 22 and 29.

Over the next several years, SDC hired thousands of programmers and other staff to develop and then roll-out the SAGE software, making the company by far the largest software developer in the US. The first SAGE site came online in 1956, and by 1961 all SAGE sites were operational.

Experience on SAGE subsequently made its way into large civilian software projects. The design of SABRE, a computer airline reservation system developed by IBM in the late 1950s, was based on SAGE. Similarly, SAGE programmers quickly diffused into other companies. In 1958, the annual attrition rate at SDC was 20%, and only 50% of SDC staff stayed more than four years. By 1960 there were 3,500 SDC employees, and 4000 ex-SDC employees. By 1963 those numbers had climbed to 4300 and 6000.

Part of SDC’s high attrition rate was because of government pay limitations: as demand for programming talent grew, SDC staff found they could go to defense or electronics companies like Northrop or Litton and double their salaries.1 And part of it was because, as work on the SAGE system progressed, the programming work shifted from creating the system to deploying and maintaining it. This was less glamorous work which had little opportunity for advancement, and as a result many of the most ambitious employees went elsewhere. However, SDC considered part of its mission to be a “university” for programmers, and thus didn’t oppose its trainees leaving for more desirable jobs. As a result of this attrition, ex-SDC employees became the “ground floor” of the burgeoning field of what was then called electronic data processing. One SAGE veteran noted that by the 1970s “chances were reasonably high that on a large data-processing job…you would find at least one person who had worked with the SAGE system”.

There are many cases where government efforts are crucial in bringing some new technology into existence. The jet engine, the nuclear reactor, the process for producing metallic titanium. One consequence of this is that government funding not only helps create the physical technology itself, but the knowledge and expertise surrounding it. Bringing nuclear reactors into existence meant more than building the physical reactors, it meant training folks who would, by the end, have expertise in building them. With computers, government funding not only helped fund the creation of the first electronic computers, but it helped train the first generation of computer programmers.

SDC certainly had the major load for programming and ongoing training for SAGE. Search You-Tube for an interesting video that documents that work. However there was some initial programming of the operating system done by Lincoln Labs who took over the Whirlwind development and then turned that over to Mitre. There is a memoir on that by John Jacobs [The SAGE Air Defense System, a personal history, Mitre, 1986]. John was there when I joined Mitre in 19984 and was handing out the book.

In the middle 70's the City University of New York offered programming courses to interested faculty. I attended a session and discovered that Fortran wouldn't help me teach Freshman Composition, or develop a program that would. About an hour into the session a knowledgeable attendee pointed out that the sample program couldn't run. The instructor looked at it for a moment and said, offhandedly, 'Yeah, it's a fake." I didn't return for the afternoon session, but eventually an application was developed that I and my colleague could use to create a 1st draft revising application that proved helpful. Then, of course, came the information revolution which proved immensely useful but which depended on processing and communication powers that were non existent in the '70's.