How China Became the World’s Biggest Shipbuilder

Since 2017, China has been the largest shipbuilder in the world. Of the 89 million deadweight tons of commercial ships built in 2024, 50.8 million of them (57%) were Chinese.1 China has a similarly large fraction (59%) of orders for new ships worldwide. Of the 20 largest shipyards in the world by the size of their order book, 14 of them are Chinese. According to the US Navy, China’s shipbuilding capacity is over 200 times that of the US. In 2023 China delivered 972 commercial ships; the US delivered 7.

China’s shipbuilding dominance didn’t happen overnight, but followed years of effort, investment, successes, and setbacks: China’s was left with little to no shipbuilding capabilities following the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, and it wasn’t until the mid 1970s that China began exporting ships. In 1982 China was ranked just 16th in ship exports. Even after China became one of the world’s major shipbuilders in the 1990s (ranking 3rd behind Japan and Korea), it was still only producing a single-digit percentage of total commercial shipping tonnage. China finally surpassed Japan and Korea in tonnage produced in 2009 and 2010, respectively.2

Despite a collapse in the worldwide shipbuilding market following the Global Financial Crisis, China has since continued to expand its dominance. While it’s produced all kinds of ships over its history, for the most part its ship exports have consisted mostly of relatively simple ships like tankers and bulk carriers.3 More specialized, complex ships like liquified natural gas (LNG) carriers and cruise ships historically remained the purview of producers like South Korea, Germany, and Italy. But as China’s shipbuilding capabilities have grown, it has encroached into these areas as well. China now has 34% of the world orderbook for LNG, including an enormous order for 18 LNG carriers from Qatar which was the largest shipbuilding order in history. China’s first domestically-produced cruise ship, the Adora Magic City, first sailed in 2024.

Shipbuilding after the birth of PRC

Prior to the formation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China was a minor player in the global shipbuilding industry.4 Between 1865 and 1949 China only built around 500,000 deadweight tons of steel ships (roughly the capacity of 46 Liberty Ships, or about a half a Liberty Ship per year). This is about 1% of the shipping tonnage the US produced during WWII, and about 20% of what a single large shipyard will produce in a year today. And following the end of the Chinese Civil War, what little shipbuilding capabilities China had were hollowed out: As the Nationalists evacuated to Taiwan, they stripped the largest shipyards of equipment, and “dynamited what remained.” In 1949 China’s largest shipyards lay in ruins, and it had fewer than 1000 shipbuilding machine tools and less than 10,000 trained shipyard workers.5

But a capable shipbuilding industry was valuable for China, both for naval purposes and for the transportation of goods. Most of China’s population was concentrated on the coasts (making coastal cargo trade important), and while road and rail networks were sparse (China had less than 5000 miles of usable rail network in 1949), large rivers allowed access to China’s interior by ship. Additionally, large oceangoing ships were in short supply following the end of the civil war, as were sailors to sail them. As the Nationalists evacuated for Taiwan, much of China’s oceangoing fleet went with them, and in 1950 China had just 77 large merchant ships (ships which carry passengers or cargo), many of which were so damaged they couldn’t move under their own power. Most Chinese waterborne trade was carried via hundreds of thousands of traditional Chinese “junks”: small, wooden, sail-powered vessels. Following the end of the war, China began to repair the damaged ships that had been left behind, buy ships abroad, and build its own ships.

China’s early post-war shipbuilding efforts were buoyed by assistance from the Soviet Union. In 1950, the two countries signed the “Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Aid,” and in 1953, they signed and a naval agreement in which the Soviets promised financial support and technical assistance for shipbuilding and shipyard redevelopment. Dalian Shipyard, originally built by the Russians in 1898, was also returned to China in 1955. The Soviets helped turn ship repair facilities into shipyards at cities like Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Tianjin. They also helped establish ship research and design groups (such as the Shanghai Institute of Shipbuilding, modeled after the Leningrad Institute for Shipbuilding).

Chinese shipbuilding progressed slowly in the 1950s and 1960s, and most efforts were focused on naval vessel construction. Following the war, China didn’t build its first steel cargo ship until 1955, and by 1960 it was only building around 10 mostly small cargo ships per year. What little progress there was stalled following the Sino-Soviet split in 1960, and the withdrawal of Soviet shipbuilding assistance and Soviet-built ship components. (The Soviets had apparently in large part been operating the Chinese shipyards.) China’s rate of ship construction fell from 10 ships in 1960 to just two ships in 1961, one ship in 1962, and zero ships in 1963; before picking back up to five ships per year. Most ships that were produced were “obsolete Soviet designs still on hand from previous years”. China’s leadership in the early 1960s seemed to have little interest in a strong shipbuilding industry. Liu Shaoqi, then Vice Chairman of the CCP, allegedly stated that “it’s better to buy ships than build ships” and that shipbuilding that was done should be limited to just the ships, not the engines.

Which isn’t to say that China made no efforts to improve its shipbuilding industry during this time. China consolidated shipbuilding efforts under the Sixth Ministry of Machine Building in 1963, and sent teams to Western and Eastern European shipyards to learn modern principles of shipbuilding shipyard design. But these efforts mostly focused on naval construction, and building merchant ships remained a challenge. The “Dongfeng” a 11,400 dwt cargo ship celebrated as being of Chinese design and built entirely with Chinese components, had to wait six years after its 1960 launching due to a lack of engines. Shipbuilding facilities appear to have been small and/or scarce. In one case, a 5,000 dwt ship was built on a beach due to the lack of a proper berth. And while Japan was building 100,000+ dwt ships using 300+ ton gantry cranes, Chinese yards often struggled to even build 20,000 dwt ships: In his 1991 study of the shipbuilding industry, Daniel Todd relays a story of a Shanghai shipyard that was forced to figure out how to assemble a 20,000 dwt cargo ship in facilities meant for just 3,000 dwt ships:

Fit for working on only at low tide, the ship’s rear ‘section was assembled upside down. There was no crane in Shanghai big enough to turn it right-side up. The workers sealed it, pushed it into the river, and there with the water taking most of the weight, used a borrowed crane to turn it over.’

Shipbuilding worsened following the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. The purging of managers and technical experts, along with Mao’s “Third Front” plan to relocate defense industries to China’s interior, hampered industrial development of all kinds, including shipbuilding — though oceangoing shipbuilding was less affected due to its need for deep water access. Shipyards became “paralyzed by political extremism,” and the Sixth Ministry which oversaw shipbuilding was split into rival factions, bringing shipbuilding to a halt at several yards until the navy intervened. The ships produced were of questionable quality, and a focus on metrics like total tonnage produced resulted in ships that were too large for most of China’s ports, and without proper cargo handling equipment. China continued to expand its merchant fleet during this period, but did so primarily by importing ships, instead of building them.

The shipbuilding industry remained enmeshed in political struggles in the 1970s: Factions battled over whether China’s merchant fleet should be expanded by buying ships (favored by the “rationalists”) or building them (favored by the “radicals”). Ship output rose and fell, depending on which faction was in power.6 This continued until Mao’s death in 1976, when the radical faction was purged and emphasis shifted from shipbuilding to buying yet again.

As China’s state-owned shipping companies had begun to favor foreign over domestic shipbuilders, China’s shipbuilding industry took tentative steps into the international market and building ships for export. China’s first export orders for small ships (less than 5000 dwt) were booked in 1975, and for larger ships in 1977. To improve its shipbuilding capabilities following the end of the Cultural Revolution as part of the broader “reform and opening up,” China solicited foreign assistance to help upgrade its shipyards, which were roughly at the level of development they had been when the Soviets left in the early 1960s. Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (then one of the world’s largest shipbuilders) was contracted to help modernize China’s largest shipyard at Jiangnan, and the UK’s British Shipbuilders and A&P Appledore were brought in to help upgrade shipyards at Dalian and Guangdong. Via these agreements the infrastructure and layout of the shipyards was upgraded, modern shipbuilding technology was brought in, and Chinese shipyard workers were given extensive training. In 1980 China also formed its first (but far from its last) shipbuilding joint venture via YK Pao’s Hong Kong-based Worldwide Shipping, then one of the largest shipping companies in the world. The new venture, named International United Shipping and Investment Company, would contract for ships to be built in Shanghai, using modern shipbuilding technology.

As it upgraded its shipyard facilities with foreign assistance, China also began to obtain licenses to manufacture foreign ship technology. Starting in the late 1970s, China began local production and assembly of foreign-designed ship components, such as marine diesel engines, electrical generators, deck cranes, and steering machinery. (Chinese producers often struggled to manufacture these components at the required level of quality, and much of this work was simply final assembly using foreign-produced parts.) The late 1970s and early 1980s was also when foreign certification societies, like Lloyd’s Register, began overseeing Chinese ship construction and certifying Chinese ships. Without these certifications, ships would have great difficulty getting insured, making ship owners very reluctant to buy them. By 1983, 90% of ships built in China for export were certified by Lloyd’s.

By the end of the 1970s, China had exported a handful of ships and was offering to export ships priced 5-15% cheaper than other producers. Despite the low quality and outdated technology of Chinese ships, Chinese shipyards had accumulated an orderbook for 900,000 deadweight tons for export by 1982 — mostly bulk carriers, oil tankers, and other similarly simple ships — more than the capacity of all existing Chinese shipyards. And while for most of its history most of China’s shipbuilding was for naval vessels, by 1981 more than 60% of shipbuilding was for civilian cargo ships.

Shipbuilding in post-reform China

By the early 1980s, China was finding some success in the ship export market, and had substantially developed its shipbuilding industry. A 1976 CIA study noted that ““the past decade has shown a dramatic increase in China’s shipbuilding capabilities”. But China’s shipbuilding industry was still far behind international leaders like Japan and Korea. China’s ship and shipyard technology was out of date, ship quality was low, and deliveries were often late. In an apparent holdover of Mao’s emphasis on self-reliance, individual shipyards still tried to produce as much as they could in-house, including shipbuilding equipment, which had created a highly fragmented industry with few economies of scale. And even with the empahsis on in-house production, low technical capabilities meant that most critical ship components had to be imported from abroad. Responsibility for shipbuilding was similarly fragmented among various ministries, agencies, and local governments. And while the industry had begun to produce ships for export, China placed little emphasis on tailoring production to meet market demands: shipyards simply sold the same sorts of ships that they were producing for domestic purposes.

But a period of great reform to China’s shipbuilding industry began in 1982. That year, in an effort to improve the industry’s performance, China consolidated nearly all shipbuilding efforts into a single state-owned enterprise, China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC). CSSC oversaw 26 shipyards, 66 factories, 33 R&D units, 3 universities and marine schools, and a workforce of roughly 300,000.

The original goal of CSSC was simply to more effectively carry out China’s existing shipbuilding policy: Build ships primarily for the domestic market while selling some similar ships for export. But a downturn in the global ship market in the early 1980s (coming on the heels of a much larger downturn from the industry’s 1970s peak) left shipbuilders around the world with huge amounts of excess capacity and desperate for new orders. From 1981 to 1982 the price for new ships declined by more than 40% on average. Ships were so cheap, and offered on such favorable terms, that it was cheaper for China’s primary shipping enterprise, China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), to import ships than buy them from CSSC. In spite of the efforts made to improve the industry, shipbuilding remained a low priority for China’s top leadership, and COSCO was under no pressure to purchase domestically-produced ships. In 1982 and 1983 more than 90% of COSCO’s ship orders went to foreign shipyards. At the same time, the weak shipbuilding market caused CSSC’s export orders to dry up: new orders fell from more than 300,000 dwt in 1981 to less than 100,000 in 1982.

Unable to rely on a captive domestic market, CSSC was forced to try and make its export offerings more competitive to keep its shipyards occupied (as a state corporation for a communist country, there was no risk that CSSC would go out of business, but apparently due to political considerations it couldn’t simply allow its shipyards to sit idle). However, the sorts of ships it had traditionally focused on building – relatively simple bulk carriers and tankers – were in low demand in the cutthroat shipbuilding market of the early 1980s. China’s shipyards thus began to hunt for orders for any type of ship at all, including more advanced ships that they had traditionally eschewed such refrigerated containerships, roll-on/roll-off (ro-ro) car carriers, and chemical carriers. In the mid 1980s China secured orders for two 69,000 dwt chemical carriers and a 125,000 dwt shuttle tanker7 from Norwegian shipowners, as well as two small containerships and two ro-ro ships from the Japanese.

While traditionally China’s shipyards had sought to maximize domestically-produced components and to minimize foreign involvement in ship production, CSSC found itself relaxing these requirements in its quest to fill its order books. The Norwegian ships were Norwegian-designed, used equipment and materials imported from Europe, and subcontracted some of the work to Norwegian companies. The containerships for Japan similarly were built with imported equipment and steel plate from Japan. One shipowner in the 1980s claimed that his Chinese-built ships were simply assembled in China using Japanese-produced parts.

In an effort to make its offerings more competitive and fill its empty shipyards, CSSC also undertook other improvements in its shipbuilding operations. At the time, ship construction times were long and unpredictable, due in part to bureaucratic delays in decision-making and material procurement. A mid-1980s shipbuilding study that compared lead times in a Chinese and Japanese shipyard found that the Chinese yard required up to six months more time to procure material. In one case, a refrigerated containership built for a German customer was delivered a year late because of difficulties obtaining the steel:

At first, steel was to be imported from Japan, until the relevant national foreign trade corporation, China National Metals and Minerals Import and Export Corporation, mysteriously refused Hudong’s request. Subsequent plans to obtain the steel domestically were nixed when the shipment, coming from the inland port of Wuhan, was physically stranded in river traffic and could not be transported in time. When CSSC tried again, this time successfully, to import from Japan, the effort was still stymied, in this instance by a requirement that imports of products similar to those made in China be transported by Chinese ships. Due to congestion at Tianjin – hardly the most logical port for receiving goods destined for a shipyard in Shanghai – the ship carrying the Japanese steel had to berth outside the port, further delaying delivery. When the steel finally arrived at the yard, 18 months had already elapsed in the 25-month delivery period stipulated in the contract.

But CSSC’s construction times improved, as individual shipyards gained more autonomy in their operations: Shipyards gradually gained the ability to negotiate individually with foreign shipowners, equipment manufacturers, consultants, and classification societies. They were given more leeway to use foreign-produced ship designs, to make their own equipment and material purchases, and exercise more managerial control over their operations. Steel plate, for instance, had previously only been distributed twice a year from the Ministry of Metallurgy, forcing yards to plan very far in advance and resulting in frequent steel shortages and delays. But by the mid-1980s, yards were being given more control over acquiring materials outside of set schedules. Contracts began to be used to manage responsibilities between different organizations within CSSC, and bonus systems were implemented to motivate workers. Slowly, CSSC started to become more of a coordinator of somewhat (but only somewhat) independent shipyard companies, rather than a single monolithic enterprise. As a result of these and other improvements, ship delivery times improved. CSSC’s large shipyard at Jiangnan halved its delivery times over the course of the 1980s, and by the end of the decade some Chinese yards were actually delivering ships early.

CSSC also worked to improve its capabilities in other ways. It continued to license foreign ship technology — by 1986 it had signed over 200 contracts for licensed manufacture, co-production, and other similar arrangements — while also improving its manufacturing capabilities so more components could be produced domestically rather than assembled from foreign-produced parts. It improved its financing offerings for ship buyers, offering credit terms more in line with those offered by foreign builders. It upgraded facilities at various shipyards, restructuring and consolidating their operations and installing more modern production machinery. While at the beginning of the '80s shipyards strived to be autarkic, vertically-integrated operations that could produce any type of ship, over the decade shipyards began to specialize: some yards focused on tankers, some on containerships, and so on. Yards experimented with new management practices and invested much more in management training.

China’s shipbuilding industry remained behind countries like Korea and Japan in the 1980s. Shipbuilding facilities were small compared to the largest foreign yards: China’s largest drydock (a flat, floodable basin on which ships are built) in 1985 could produce ships up to 100,000 dwt, while in Japan the largest drydocks could produce ships ten times that size. China wouldn’t complete a 250,000 dwt drydock, allowing it to build the very largest crude oil tankers, until the mid-1990s. Shipyard crane capacity was similarly limited, and while the block method of construction had been adopted by Chinese yards (it’s unclear exactly when, but at least by 1982), blocks were smaller and less fully outfitted compared to the most modern foreign yards, and were wastefully moved around yards far more often. China’s shipyard facilities in the 1980s were described by visitors as operating on the level of 1950s or 1960s US yards. In some cases unreliable electrical grids forced shipyards to supply power via their own generators. Shipyards were staffed with far too few engineers, and low labor productivity meant that yards employed a very large number of blue collar workers in comparison to their output.

And despite China’s efforts at technological transfer, the fraction of domestically-produced components in Chinese ships remained “disappointingly low”; even things like ship steel mostly had to be imported because Chinese steel wasn’t good enough. Designs and components were often unstandardized, and ships were frequently built based on the idiosyncrasies of whatever engineer happened to be working on the project. Ship quality had improved, but slowly, and many shipowners remained dubious. Delivery times and labor efficiency were still far behind what Korea and Japan were capable of. And while Chinese shipyards were offering prices well below international competitors, prices were set based on what would win the yard orders without regards to actual production costs, and CSSC lost huge amounts of money on many ships that were underbid. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Chinese shipyards began to factor profit and loss into their operations.

But while China’s shipbuilding industry was still behind the world leaders, CSSC’s shifting emphasis towards exports and transforming its operations to meet the needs of the market gradually bore fruit. By the late 1980s CSSC was producing half of its ships for export, up from 1/3rd in 1982. By 1991 China had exported ships to 30 different countries, and by 1992 it had become the third largest commercial shipbuilder in the world, up from 16th in 1982.

Shipbuilding in the 1990s

China’s shipbuilding industry continued to slowly improve in the 1990s. Shipbuilders became increasingly cost-conscious, as CSSC headquarters had begun to more closely monitor shipyard bids to shipowners and reject any that they believed couldn’t be achieved profitably. Departments within shipyards began to sign contracts with each other that included delivery time and cost targets, and workers could earn bonuses by meeting them. Chinese shipyards began to walk away from bids if the price buyers demanded was too low. By 1994 maritime publication Lloyd’s List reported that “indifference to price is a thing of the past in China”, and by the mid-1990s shipbuilding was one of China’s most competitive export industries. In 1996, 85% of new merchant ships in China were built for export.

During the 1990s China continued its efforts to acquire ship and shipbuilding technology by way of manufacturing licenses, joint ventures, and technology transfer agreements. China signed agreements with Japanese and European shipyards for the transfer of technologies like CAD/CAM software, metal cutting techniques, gearboxes, and diesel and gas turbine engines. By the early 2000s nearly every major marine engine manufacturer had established a manufacturing facility in China, and Chinese shipyards had widely adopted CAD/CAM ship design software (which had been rarely used in the early 1990s). Hundreds of Chinese shipyard workers were trained in Japanese shipyards, and Chinese yards gained continued exposure to foreign design practices by producing foreign-designed ships, inviting foreign consultants to lecture in China, and partnering with foreign ship design firms. This training, information exchange, and technology transfer all helped improve China’s shipyard operations. It enabled advancements like more efficient hull blocks, which minimized material use by intelligently locating joints, and it improved labor productivity by making greater use of pre-outfitting (installing systems on hull blocks before they’re attached to the ship).

Chinese shipyards also expanded their shipbuilding capacity in the 1990s. In 1995, the shipyard at Dalian completed a 250,000 dwt-capacity drydock, the first dock in the country capable of building Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs). Over the next 10 years, China built 8 more VLCC-capable drydocks, and had another four in the planning stages. China’s total shipbuilding capacity in 1982 was 800,000 dwt annually. By 1997 it had reached 2.5 million dwt, and investments were being made to increase that to 3.5 million dwt.

China also took its next tentative steps with shipyard joint ventures in the 1990s. In 1991, German shipping company Schierack Beteiligungs was so impressed with China’s delivery of two liquified petroleum gas (LPG) carriers that it established a joint shipyard with CSSC, Shanghai Edward Shipbuilding, to build more of them. And in 1994, the Yantai Raffles shipyard, a joint venture between two Chinese companies and Singapore’s Brian Chang Group, began operations.8 (Yantai Raffles is notable for being 100% foreign owned, a rare occurrence for Chinese joint ventures, and for setting records for the world’s largest revolving pedestal crane and the most weight ever lifted by a crane.)

China’s shipbuilding industry was badly shaken following the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the huge decline in new ship orders that followed. As a result, China took steps to try and further improve the industry’s operations and efficiency. CSSC slashed an estimated 1/3rd of its labor force, and to further encourage competition in 1999 the company was split into two: CSSC and China Shipbuilding Industrial Corporation, or CSIC. That same year, the government began to encourage shipyards to pursue joint ventures with foreign shipyards as a way to further acquire foreign ship and shipyard technology. Foreign operators were limited to 49% ownership (a requirement that was temporarily relaxed in 2001, then reinstated in 2006)9, and agreements included “mandatory provisions ensuring foreign technology transfer into Chinese shipyards”. One such joint venture was NACKS, a shipbuilding joint venture between China’s COSCO and Japan’s Kawasaki Heavy Industries, which became one of China’s largest shipyards. Between 1999 and 2008, NACKS constructed more than 7% of all ship tonnage built in China.

By the end of the 1990s, the status of China’s shipbuilding industry was not all that different from the end of the 1980s. It remained a distant third behind Korea and Japan in terms of output. At the end of 1999, China’s orderbook was less than 1/10th the size of Japan’s or Korea’s, and it had just 3% of total international orders. Of the 40 largest shipyards in the world by number of orders, China had just 2 (Dalian at #18 and Hudong at #22).

While China’s shipbuilding industry had made significant progress in improving its operations during the 1990s (as it had in the 1980s), China’s shipyards were still inferior to the best foreign yards in terms of efficiency, technological capabilities, and ship quality. Delivery times and quality had both improved, but they were still somewhat inconsistent, and Chinese yards were still “fairly well known” for delivering ships late and/or or poorly built: Foreign shipowners would send large numbers of advisors to Chinese yards to try and ensure the ships were built properly, but as late as 2006 Chinese yards were building ships that had to be scuttled after being rejected by the buyer for being unseaworthy. A substantial volume of ship steel (~15%) and ship components (~40%) still needed to be imported from abroad, and most ship engines were either imported or built in China from licensed foreign designs. Outside analyses of Chinese shipyards found that they often had trouble taking maximum advantage of the latest technology if they had it (and they often didn’t: In the 1990s, the majority of Chinese shipyards were estimated to have 1980s-level technology) and that Chinese yards still may not have known what their true costs of production were. Despite its efforts to build more advanced, complex ships China still had a reputation for being a cheap builder of the simplest ships, a status reflected in its orderbook. Chinese shipyards still had a sizable labor cost advantage compared to yards in Korea and Japan, but much of this advantage was offset by its low productivity. What’s more, productivity was improving very slowly as costs were rising, and there was concern that the industry was losing price and technological ground to foreign yards.

By the new millennium, China’s shipbuilding industry had progressed significantly, but it remained in a lower league than Japan and Korea, who continued to dominate world ship production.

Shipbuilding in the 21st century

In the year 2000, China’s Party Central Committee (the central governing body of China) and the State Council (roughly equivalent to the cabinet or executive branch) identified shipbuilding as a key industry for development. In 2002, Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji stated that China should become the world’s foremost shipbuilder, and the government set a target for the country to become the world’s biggest shipbuilder by 2015. The next year, China released its National Marine Economic Development Plan, which proposed building several large shipbuilding bases around the country. China’s 11th five-year economic plan, released at the end of 2005, identified shipbuilding as a strategic industry and announced goals for annual shipbuilding tonnage: 15 million dwt by 2010 and 22 million by 2015. By the time this plan was released, China’s shipbuilding output had already been steadily increasing, buoyed by an upswing in the international shipbuilding market (worldwide shipbuilding output rose more than 50% between 2000 and 2005): China’s shipbuilding output was nearly 10 million dwt in 2005, up from just 2.5 million dwt in 2000.

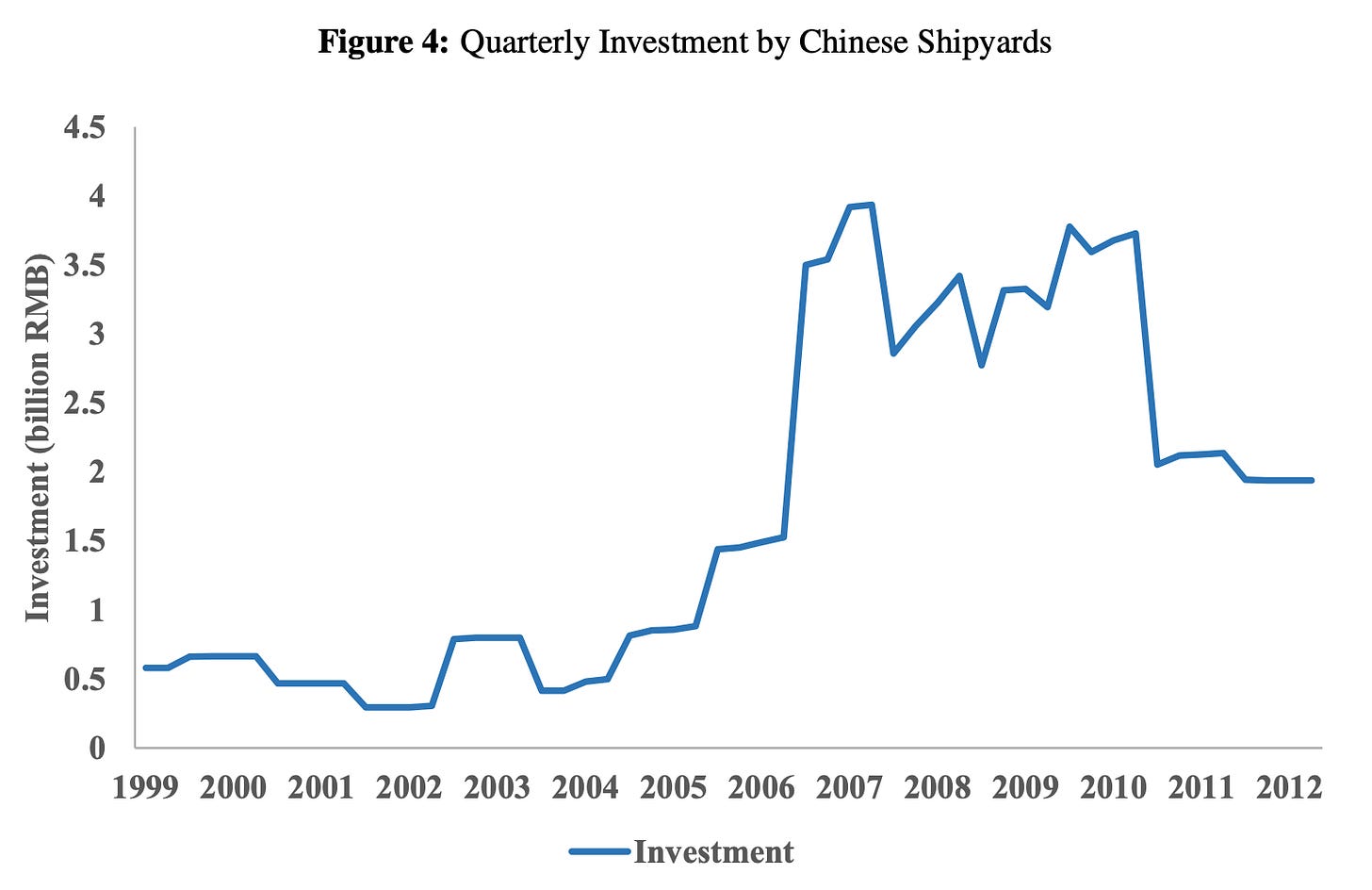

Following these new policy priorities, state investment poured into the shipbuilding sector. It’s estimated that the government spent $90 billion subsidizing the shipbuilding industry between 2006 and 2013, contributing an estimated 15-20% of the cost of each new ship. Between 2004 and 2007, annual investment in Chinese shipyards rose by a factor of seven. Dozens of new shipyards began construction, including huge sites at Changxing Island, Longxue Island, and Bohai. In some cases, entire shipyards were relocated to new facilities: Jiangnan shipyard, historically one of China’s largest shipyards, was moved to Changxing Island to clear room for the Shanghai Expo 2010. These new shipyards were largely “greenfield” sites with plenty of space and huge drydocks, including a 1,000,000 dwt capacity dock at Yantai. They were designed for efficient material flows and incorporated modern shipbuilding technology.

Much of this investment went into CSSC and CSIC-operated yards, but the industry also expanded outside of these two state-owned giants. Scores of smaller yards operating outside the auspices of CSSC and CSIC cropped up, many of them simple “beach” yards with little in the way of infrastructure or government oversight. And many large privately owned shipyards, operated by both foreign and local companies, were built as well. By 2012, only 8 of the 20 largest shipyards in China were operated by CSSC or CSIC.

Prior to these initiatives, China has already been capturing a greater share of the world shipbuilding market: By 2005, it had reached nearly 14% of new deliveries, and 16% of the global orderbook (up from 5% and 9% in 2000). But the huge amount of investment in the sector threw gasoline on the fire: China’s orderbook surpassed Japan’s in 2007. It surpassed Korea’s in 2009. China met its goal of producing 15m dwt by 2010 in 2007, and met its goal of producing 22m dwt by 2015 in 2009. In 2010, China produced more ships (whether by number of ships, deadweight tons, or gross tons) than any other country in the world, and in 2012 it produced roughly as much tonnage as the entire world had in 2002.

As China expanded its shipbuilding infrastructure and captured a larger share of the global market, it continued its efforts to acquire foreign shipbuilding technology through partnerships and joint ventures with Japanese, Korean, and European firms. In 2006, when reverting the rules for foreign investment to limit foreign ownership of shipyards to 49%, China also required that foreign partners set up technological transfer centers to transfer expertise to local partners. In 2009, an executive at CSSC published an article stating that Chinese shipbuilders should focus on “introducing, digesting, absorbing, and re-innovating” foreign technology. It apparently became common for Japanese and Korean engineers to offer consulting services to China and for Chinese shipyards to hire retired Korean engineers. It’s estimated that following the downturn of Korea’s shipbuilding industry in the late 2010s, roughly 2000 former shipyard workers left Korea for China:

China must have thought, ‘This is the moment.’ They recruited many engineers, and they must have been after things like the design drawings that they kept privately. Chinese shipbuilding companies tried to recruit Korean engineers by offering them ‘annual salary of 300 million won [~$216,000 USD], 2-3 year contracts’ as if it were a formula. They just sucked up the juice and sent them away when the 2-3 year contracts were up.

China’s desire to absorb their expertise did little to dissuade foreign firms from entering China, enticed by China’s large market and low costs of labor. Qingdao Hyundai Shipbuilding, a joint venture with Korea’s Hyundai, was founded in 2005, and STX Dalian, a venture of Korea’s STX group, began operations in 2006. Kawasaki’s joint shipbuilding venture NACKS founded another joint shipbuilding operation, DACOS, in 2007. In 2005 alone, China’s shipbuilding industry filed 104 proposals for foreign investments or joint ventures. Foreign joint ventures in China’s shipbuilding industry continue to be widely used today, and new ventures continue to pop up all the time.

Shipbuilding since the financial crisis

The huge expansion of China’s shipbuilding industry was derailed by the 2008 global financial crisis. Orders for new ships collapsed worldwide, and ship prices fell by roughly 50% (depending on the ship). Only after Covid has the shipbuilding industry shown signs of bouncing back: Orderbooks have risen 65% in the last 4 years, but orders and deliveries are still down from the pre-crisis peak.

China was hit especially hard by the industry slowdown. Much of its expansion in capacity had come by way of building numerous small, inefficient shipyards poorly equipped to weather a major decline in the global shipbuilding market. By 2010, China was only using 75% of its shipyard capacity, and by 2015, that had fallen to 50%. Many shipyards went bankrupt or ceased operations. Rongsheng Heavy Industries, previously the largest privately-owned shipbuilder in China, shuttered its operations in 201410. STX Dalian declared bankruptcy the same year. Across the country, shipyard facilities sat idle, and the formation of new shipyards declined precipitously.

As a result of its struggles, the Chinese government took steps to shore up the shipbuilding industry. It created a scrap and build policy to encourage shipowners to dispose of older ships in favor of new ships. It rolled out extremely attractive financing options, allowing shipowners to buy ships with as little as 2% down payment.11 And it encouraged shipyards to merge and consolidate in order to become stronger and more internationally competitive. Due to the ebb in merchant ship orders, this consolidation often took the form of combining shipyards that had civilian orders with shipyards that had military orders, so the financial strength of the latter could support the former. (One such consolidation was CSIC and CSSC, which began to re-merge in 2019 following years of discussion.) But only the largest and most productive shipyards (as well as shipyards that produced military vessels) were flagged as eligible for support, and between 2010 and 2019, the number of active shipyards in China declined by 70%. Despite this consolidation, even today China’s industry remains comparatively fragmented compared to Korea. While China has a large fraction of the world’s largest shipyards, and most of the world orderbook by capacity, the largest shipyards in the world by maximum output remain Korean.12

In relative terms, China’s shipbuilding industry managed to stay on top in spite of its struggles. China remained the world’s largest shipbuilder by output from 2010 to 2014, and while Korea regained the top spot in 2015 and 2016, China has held on to first place since 2017.13 Still, China’s shipbuilding industry faced perennial challenges throughout its expansion: While Chinese yards maintained a labor cost advantage compared to Japan and Korea, it was still less labor efficient in terms of output per man-hour (as well as in terms of output per square meter of shipyard) in the 2010s.14 Productivity improved slowly due to work being spread across a comparatively large number of shipyards, which hampered learning curve effects. China still had comparatively few engineering personnel in shipyards compared to Korea or Japan, and such personnel were mostly allocated to naval rather than commercial work. Shipyard turnover was high, and Chinese ships still took longer to build than Korean and Japanese ships. They were also still considered to have worse quality, being noisier, dirtier, and less fuel efficient than Japanese or Korean ships. The result was that Chinese ships sold at a discount compared to Korean and Japanese vessels, and they maintained much less of their value in the secondary market. Experts estimated that for many complex types of ships, China was still several years behind the world leaders.

China also continued to struggle to produce many of the sub-components and materials needed for shipbuilding. While China became apt at building marine engines (based on licensed designs), it still needed to import many components including electrical equipment, navigation equipment, cabin outfitting equipment, and specialty steels (including the steel used for the exterior hull). Estimates in the mid-2010s pegged China’s level of domestic production for components at 55-60%, compared to 80-90% in Korea and Japan. A 2013 CSIC report noted that while the company excelled at “‘building the empty shells,’ we basically use foreign products inside the ships, including the propulsion system, the communication system and the navigation system with high added value and high technical contents.” And while China had successfully built complex vessels like LNG carriers15 (which need to be built to strict tolerances to ensure the liquified gas stays insulated and cold), it purportedly struggled to build them, and China’s share of the LNG market was in the single digits as late as 2021. Well into the 2010s, China’s bread and butter remained simpler ships like tankers and bulk carriers.16

But as it has since its inception, China’s shipbuilding industry has continued to march forward. China’s overall share of the world orderbook rose from 40% in 2010 to 57% at the end of 2024. It has now captured 30% of the LNG market, 45% of the LPG market, and 70% of the market for large container ships. In 2024, China secured 75% of new ship orders. It’s continued to partner with foreign firms across the shipbuilding value chain, and simultaneously increase its quality and productivity: one expert recently stated that “the quality gap has closed a lot over the last 15 years or so,” with the quality being “in many instances as good as you’d get elsewhere.” China still lags in some areas (like building cruise ships), but it seems motivated to catch up there as well.

Conclusion

If you survey the arc of the development of China’s shipbuilding industry, you’ll see a trend of continuous (if sometimes plodding) progress, with the occasional interruption and reversion. After most 10-year periods, you could look back on the previous decade and see substantial improvement in China’s shipbuilding capabilities: China went from having virtually no shipbuilding industry at all to producing its first vessels in the 1950s, entering the export market in the 1970s, becoming an increasingly successful player in the 1980s and 1990s, and becoming the world’s largest shipbuilder in the 2000s.

But you could similarly examine where China’s industry stood at most points in time and see an industry that was still behind many of its competitors. Until very recently China struggled to build ships that were as high quality or as complex as those from other countries. Even today, as the undisputed biggest shipbuilder in the world, it seems like China still lags in producing the most complex ships, in shipyard productivity, and in producing various marine components (most engines in Chinese ships, for instance, are still based on foreign designs) — though it wouldn’t surprise me if this gap continues to shrink.

What’s notable to me isn’t that China became a major shipbuilding country. Most low-labor cost countries that have tried have been able to carve out a share of the world market, at least for a time. Japan and Korea are the obvious examples, but countries like Brazil, Poland, Yugoslavia and Taiwan also had major shipbuilding industries that were developed following WWII.

Instead, what’s notable is how long it took China to become a major player. Compared to Korea, China’s shipbuilding industry seems to have advanced slowly. Like China, Korea had little shipbuilding capability following the end of WWII (in 1962 only 8% of South Korea’s shipping tonnage was steel ships), and Korea didn’t begin exporting ships until the 1970s. But in less than a decade, Korea’s Hyundai emerged from no previous shipbuilding experience to become the largest shipbuilder in the world. By 1984, Korea had captured 17% of the global ship orderbook, and by the end of the 1980s, Korea had the world’s largest orderbook. China, on the other hand, didn’t reach a similar share of world orders until 2005, and it didn’t have the world’s largest orderbook until 2010.

(Compared to Japan, which became the world’s largest shipbuilder less than a decade after it began building up its industry following WWII, China is slower still, but this is less of a fair comparison since Japan entered the post-war era as a much more capable shipbuilder.)

While Korea entered shipbuilding in the 1970s with a full-throated desire to become a major shipbuilder, as late as the early 1990s China was apparently “not thoroughly convinced of [shipbuilding’s] usefulness.” Progress accelerated when China’s government fully embraced shipbuilding in the late 2000s, though one wonders how successful this effort would have been without the previous three decades of export experience.

Since the end of WWII, we’ve seen a regular emergence of new major players in the shipbuilding market. These countries almost always capture market share by leveraging their low costs of production (especially labor) and are often able clamber up the worldwide rankings following a major industry disruption. Japan displaced the UK as the largest shipbuilder in the world following WWII and the invention of modern shipbuilding methods; Korea emerged as a major shipbuilder following the collapse of the shipbuilding market in the late 1970s, eventually muscling Japan out of the top spot. China in turn displaced Korea following the huge expansion, then contraction, of its shipbuilding industry in the 2000s and early 2010s. It remains to be seen if a similar pattern will befall China (perhaps by a country like Vietnam, whose orderbook quadrupled between 2020 and 2024), or if China will be more successful at maintaining a hold over the industry.

There are several measures of ship capacity.

Deadweight tons (dwt) is the total amount of weight a ship can carry.

Displacement tons is the weight of the ship itself.

Gross tons (GT) is a measure of internal ship volume.

Compensated gross tons (CGT) is similar to Gross Tons but with an adjustment to try and correct for the fact that some ships are more complex to build than other types. It's a measure of effort it takes to build a ship, and is used to compare the output of different shipyards (or different countries) that might be producing very different types of ships.

Korea retook the lead in 2015 and again in 2016 on compensated gross tonnage produced, but since 2017 China has remained in the #1 spot.

Relative complexity of different ship types:

China did manage to produce an all-welded cargo ship in 1947, prior to Japanese yards performing similar feats.

10,000 workers is less than what a single US WWII shipyard employed. Kaiser’s Swan Island Facility employed more than 30,000.

Even when focus shifted to building, China’s lack of shipbuilding capacity meant that most additions to China’s merchant fleet were still imports.

Shuttle tankers transport oil from offshore oil fields.

Chinese partner companies were China National Petroleum Company and Yantai City Mechanical Industrial Company.

Yantai Raffles, which was 100% foreign owned, was grandfathered in under the old rules.

In part because, despite its state of the art shipyard, it struggled to build actual ships.

Thanks to this program, between 2005 and 2015 European Banks’ share of ship financing fell from 70% to 30%. Over the same period Chinese banks rose from 2% to 18%.

Though some of these shipyards are adjacent to each other. Geographically, the largest shipbuilding facility in the world is likely Changxing Island.

Measured by CGT.

Though this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If you have very cheap labor, it may not make sense to displace that labor with comparatively more expensive labor-saving technology.

China delivered its first LNG carrier in 2007.

It’s important to note that this emphasis on tankers and bulkers is to some extent a reflection of global demand for ships. China’s 2015 orderbook is not all that different from the world orderbook of 2015, though China has a lower proportion of complex ships.

While I no longer have either the motivation nor the information access to do calculations, the general rule is that no one anywhere has consistently made money building ships since 1945, at least. I suspect that this holds true for China. (In my experience, albeit limited, Chinese firms are not strong at understanding their real cost structure.)

Interesting and detailed article. Thank you