How the UK Lost Its Shipbuilding Industry

From roughly the end of the US Civil War until the late 1950s, the United Kingdom was one of the biggest shipbuilders in the world. By the 1890s, UK shipbuilders were delivering 80% of worldwide shipping tonnage, and though the country only briefly maintained this market-dominating level of output— on the eve of World War I, its share of the market had fallen to 60% — it nonetheless remained one of the world’s largest shipbuilders for the next several decades.

Following the end of WWII, UK shipbuilding appeared ascendant. The shipbuilding industries of most other countries had been devastated by the war (or were, like Japan, prevented from building new ships), and in the immediate years after the war the UK built more ship tonnage than the rest of the world combined.

But this success was short-lived. The UK ultimately proved unable to respond to competitors who entered the market with new, large shipyards which employed novel methods of shipbuilding developed by the US during WWII. The UK fell from producing 57% of world tonnage in 1947 to just 17% a decade later. By the 1970s their output was below 5% of world total, and by the 1990s it was less than 1%. In 2023, the UK produced no commercial ships at all.

Ultimately, UK shipbuilding was undone by the very thing that had made it successful: it developed a production system that heavily leveraged skilled labor, and minimized the need for expensive infrastructure or management overheads. For a time, this system had allowed UK shipbuilders to produce ships more cheaply and efficiently than almost anywhere else. But as the nature of the shipping market, and of ships themselves, changed, the UK proved unable to change its industry in response, and it steadily lost ground to international competitors.

The rise of UK shipbuilding

For much of recent history, the Netherlands boasted the largest and most successful shipbuilding industry. Between 1500 and 1670, Dutch shipping had grown by a factor of 10, and by the end of the 17th century the Dutch merchant fleet, made up of mostly Dutch-made ships, was larger than the commercial fleets of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and what is now Germany combined. Dutch shipbuilding was “technologically the most advanced in Europe,” and Dutch shipbuilders could build ships 40-50% cheaper than English ones.

Over the course of the 18th century, however, the Dutch advantage was gradually eroded by “a failure to keep pace with advances in European sailing ship design and an inherent conservatism within the industry.” But while it briefly looked like the UK would come to dominate shipbuilding in the early 19th century, the mantle instead passed to the United States. By the middle of the 19th century, thanks in part to the easy availability of ship-quality lumber, the US could build wooden ships for 20 to 25% less than in the UK, and “the very existence of the British industry was under threat”.

But as wooden sailing ships gave way to iron and steel steamships over the course of the 19th century, the UK reclaimed its advantage. By the 1850s, the UK was building iron ships more cheaply than wood ships, and while it took decades for iron, steel and steam to displace wood and sail — sail remained a better option than steam for very long voyages until the 1880s — Britain’s access to cheap coal, cheap iron (and later cheap steel), and cheap skilled labor (compared to the US) allowed it to dominate the transformed shipbuilding industry. By 1900, UK shipbuilding productivity was substantially higher than in the US, and even further ahead of other countries. The UK had become the “shipyard of the world” on the back of its inexpensive production.

Structure of UK shipbuilding

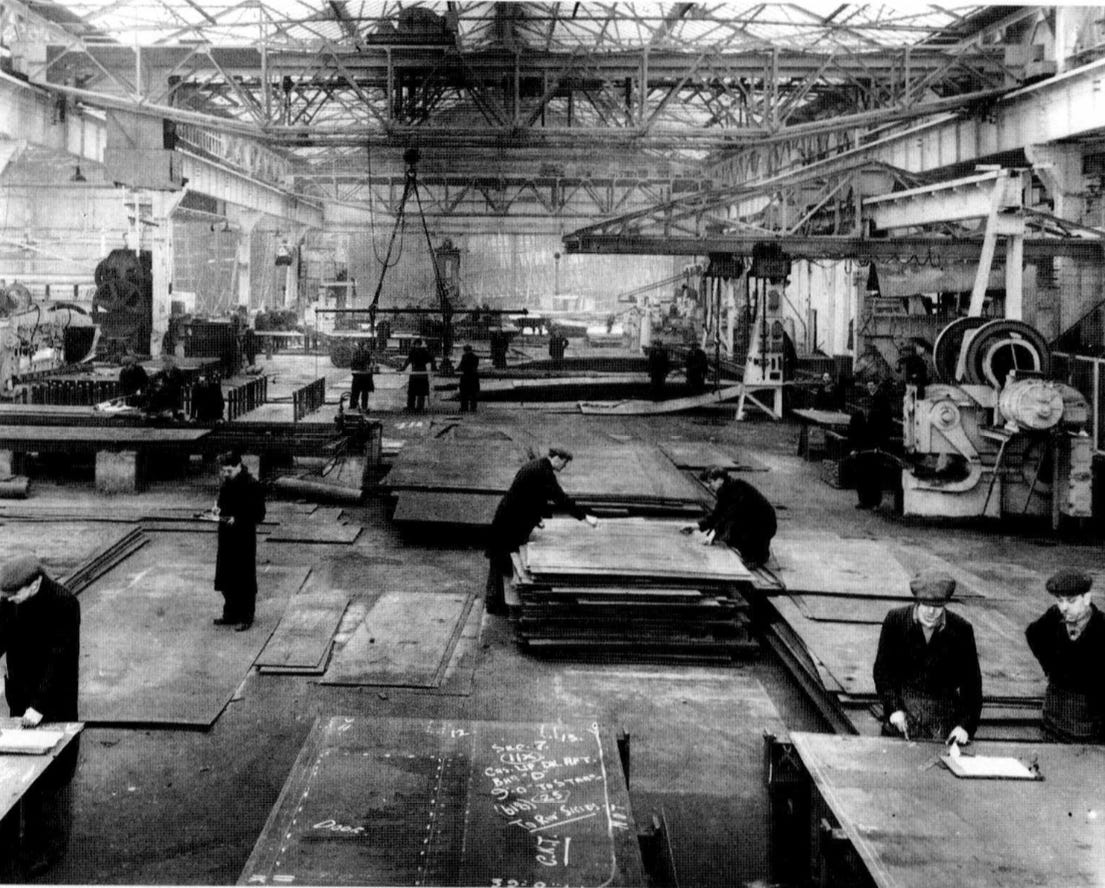

The structure of the UK’s shipbuilding industry reflected the conditions it operated under. Building iron and steel ships obviously required machinery and infrastructure — machine tools, cranes, slipways (sloped areas of ground the ship would slide down upon completion) — but wherever possible, British yards still eschewed expensive machinery or infrastructure in favor of skilled labor. British yards in the late 19th and early 20th century have been described as “under-equipped in relation to those of her competitors”: for instance, while the most advanced foreign yards had large, mechanically operated cranes that could be moved from berth to berth, most British yards “retained their fixed cranes, manually operated derricks, and push-carts on rails”. Because of the notoriously cyclical shipbuilding industry, which often had “seven fat years followed by seven lean years”, using labor-intensive production methods let shipbuilders easily scale up and down their operations depending on demand: workers could be hired when they were needed, and quickly fired when weren’t. A capital intensive production operation, by contrast, couldn’t easily reduce its overheads during a downturn: one extremely large, modern, and expensive British shipyard at Dalmuir was forced to close in 1929 due to difficulty servicing its overheads when demand for new ships fell.

British shipbuilders’ production operations were in large part oriented to meet the needs of British shipowners, who made up the majority of their customers. Shipyards (and their owners) developed close relationships with shipowners, who would purchase from the same yards repeatedly; as a result, shipyards did little in the way of marketing their services. Ships in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were “expensive, custom-made commodities built in close consultation with the owner”. Frequent changes during the building process by the owner were common, and standardization was limited to non-existent. With limited ability to take advantage of economies of scale, shipyards were small and numerous, and while yards tended to specialize in certain types of ships, labor-intensive production methods made it comparatively easy for yards to adapt to producing different types of ships depending on the market.

In addition to minimizing infrastructure overheads, British shipyards had low management overheads; much of the work was performed by skilled labor organized into “squads,” groups of tradesmen which could organize work without needing much in the way of specific instructions. As a result, British shipyards employed comparatively few supervisors, and did little in the way of production planning.

Because shipyard workers had little in the way of job security, the British shipbuilding industry became strongly unionized. Iron shipbuilding was done by a group of 15 different unions — riveters, boilermakers, plumbers, and so on — and there were very strict rules about which unions were allowed to do which tasks. This arrangement had its advantages — unions oversaw much of the training and apprenticeship of new workers, and allowed the work to be done with comparatively little management overhead. But it also had drawbacks: the union’s (rational) lack of trust in the shipbuilders, who they correctly viewed as considering their workers disposable, resulted in fierce opposition to changes in the nature of ship production, and made introducing method improvements fraught.

Cracks begin to appear

The first cracks in British shipbuilding hegemony began to appear after World War I. Immediately following the war, the world saw a huge increase in demand for ships: in 1919, worldwide ship production was 7.1 million gross tons, up more than double the pre-war peak of 3.3 million tons in 1913. Initially much of this output was American (thanks to the continuation of the wartime shipbuilding program past the end of the war), but as this program ended the UK was once again dominant: by 1924 the UK was producing 60% of the world’s ship tonnage.

But the competitive landscape of the shipbuilding industry was changing. Worldwide shipyard capacity after the war was roughly double what it had been before it. Other countries were eager to give support to their local shipbuilding industries, and foreign shipyards were catching up to British levels of productivity.

Ships and the methods for producing them were also changing. New shipyard layouts and new production techniques such as welding were being experimented with, and new types of ships such as diesel-powered ships and tankers — kinds of ships British shipowners and shipbuilders seemed less interested in building — were increasingly in demand. When the booming shipbuilding market entered a downturn in the 1920s — worldwide ship output dropped from over 7 million gross tons in 1919 to 2.2 million in 1924 — the competitive pressure on British shipbuilders began to mount. In 1925 the British shipbuilding community was shocked when Furness Withy, a British shipping company, ordered several ships from Germany, citing lower costs and faster delivery times. The news was surprising enough that a British shipbuilding trade association called an emergency conference on the problem of foreign competition:

The employers reviewed the history of foreign competition and conceded that whilst before the war foreign competition had presented a threat, ‘the margin of difference then was sufficiently limited’ to prevent a successful challenge to our premier position and certainly such a catastrophe as an important British order going abroad’. The margin of difference, however, now favoured continental builders and there was every prospect of more British orders going abroad and fewer foreign orders coming to the UK.

What’s more, the postwar boom in shipbuilding had created a huge glut in ships and shipbuilding capacity. In the early 1920s British shipbuilding had a third more capacity than it did before the war, only to be faced with demand less than half of what it was in 1914. By 1933, worldwide seaborne trade was down 6% from 1913, but the tonnage of merchant ship capacity was up by 49%, greatly reducing demand for new ships.

British shipbuilding was further hamstrung by the Washington Naval Treaty, which was signed in 1922 and then extended by the London Naval Treaty in 1930. The treaty, signed by the UK, the US, France, Italy and Japan, attempted to prevent a naval arms race by limiting naval vessel construction for each signatory. What had been a robust British program of naval expansion was suddenly halted. Following the treaty, British naval shipbuilding fell by over 90%.

The lack of shipbuilding, increased pressure from foreign competition, and the global decline in new ship orders wreaked havoc on the British shipbuilding industry in the 1920s and 30s, to the benefit of its competitors. The UK’s fraction of worldwide ship tonnage produced declined from 60% in 1924 to 50% by the end of the 1920s, to less than 40% by the mid-1930s. Over the same period, Germany, Sweden, and Japan’s combined share rose from 12% to 36%. Numerous British shipbuilding firms ceased operations, and shipbuilding unemployment rose from 5.5% in 1920 to over 40% in 1929. In the first 9 months of 1930, only one in five of British shipbuilders received any orders at all.

To help address the problem of excess shipyard capacity, British shipbuilders banded together to form the National Shipbuilders Security (NSS) company, which was funded to “assist the shipbuilding industry by the purchase of redundant and/or obsolete shipyards and dismantling and disposal of their contents.”. By 1938, over 216 ship berths had been demolished. The NSS also made efforts to try to improve productivity and improve the competitive position of British shipyards compared to foreign yards, though it’s not clear if this had much impact: by 1938, foreign orderbooks appeared far fuller than British ones, and the industry was palpably worried about the threat of foreign competition. It wasn’t until the Royal Navy began a period of rearmament in the late 1930s in anticipation of war that fortunes began to improve for the UK shipbuilders.

Post WWII

Following the end of WWII, fortunes initially looked bright for the British shipbuilding industry. German and European shipbuilding capacity had been devastated by the war, the US was dismantling its enormous wartime shipbuilding machine, and Japan was forced to cease ship production. In the immediate years following the war, the UK was once again producing more ship tonnage than the rest of the world combined.

But the issues of foreign competition that had increasingly threatened the UK’s dominance prior to WW2 had only retreated temporarily. What’s more, during the war, developments had taken place that would threaten the skilled labor-intensive production model that British shipbuilders relied on. To win the Battle of the Atlantic and overcome destruction to their fleet caused by German U-boats, the US had used welded, prefabricated construction to rapidly build enormous numbers of simple cargo ships: Liberty ships, Victory ships, and T-2 Tankers. In the 1950s, those methods of ship construction were brought to Japan, where they continued to be refined.

British shipbuilders could have taken advantage of these methods as well. They had seen firsthand the huge number of Liberty ships American shipyards were producing (the Liberty ship was, after all, originally a British design), and had made use of welded, prefabricated construction themselves to build vessels during wartime. But British shipbuilders perceived adopting these radically different production methods as risky. It would require enormous capital expenditure, and British shipbuilders had only survived the brutal 1930s thanks to their comparatively light overheads and labor-intensive methods. Dramatic changes to production methods would also require changes to the very strict demarcation system of its unionized labor force, which the unions, naturally distrustful of shipyard operators, were sure to resist. And while the US had successfully built thousands of ships very rapidly during the war, it had come at a cost: the US cargo ships, using modern methods, were more expensive to build than similar British ships. Though some British shipbuilders recognized the potential of welding and prefabrication, they weren’t clearly worth reorganizing the entire industry around.

And beyond their rational reluctance, British shipbuilders were simply not predisposed towards adopting radical innovations. Many of them (along with many British shipowners) were suspicious of welding, partly due to natural conservatism and partly due to several high-profile failures where welded ships cracked in two. (As late as 1954, British shipbuilders noted that “owners do not want a welded box, they expect plenty of riveting.”) British shipbuilders similarly proved somewhat reluctant to enter the world of tanker and diesel-powered ship construction, which were becoming an increasingly large fraction of ship construction. They also seemed to always have an excuse for not making large, new capital investments: when the yards were busy, such investments were disruptive and made it difficult to get on with the business of building ships, and when they weren’t, there was no funding available to do so. Shipbuilders were often small, family-run businesses, sometimes by descendants of the original founders, and they were generally happy to simply carry on business as they always had. And broader ownership did not foster innovation either, with firms distributing their profits as dividends rather than reinvesting them in the business, driving the stock prices of shipbuilders up more than any other manufacturing industry.

Moreover, British shipyards tended to be cramped, with little room for expansion, and British shipbuilders were fearful that any postwar boom in shipbuilding would (once again) be followed by a bust, requiring retrenchment and making investment in expanding facilities unwise. (One British shipbuilder predicted that “it will be a case of last in, first out, and that Britain’s policy of modernising her shipyards without any great expansion of their capacity will pay dividends in her future competition.”)

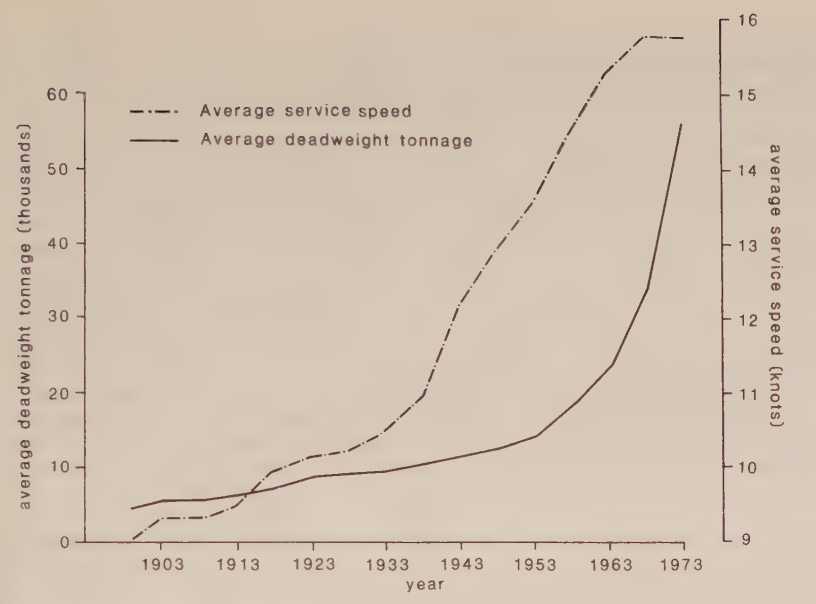

Thus, even as the world shipbuilding market boomed in the 1950s, UK shipbuilding output stayed roughly constant. Between 1947 and 1957, UK ship output rose by 18%, while worldwide output comparatively rose by over 300%. Countries like Germany, Sweden, and Japan picked up the slack. The UK lost its position as the world’s biggest shipbuilder by tonnage to Japan in 1956. By the end of the 1950s, Germany and Sweden had passed the UK in ship tonnage built for export and by the end of the 1960s they were outproducing the UK in overall ship tonnage. Between 1950 and 1975, one of the largest shipbuilding booms in history, the UK was the only major shipbuilding country to not increase its output at all.

As other countries expanded their output, adopted modern production methods, and built new, efficient shipyards, British shipbuilders found themselves increasingly uncompetitive. Their costs were higher than those of foreign shipbuilders, and their delivery times were longer. Shipbuilding had traditionally been done on a “cost plus” basis, where owners were charged some percentage above costs incurred when building the ship, but owners were increasingly requiring fixed price bidding. British shipbuilders, with their comparative lack of production planning and managerial control, struggled to adapt to the new reality. British shipowners, traditionally the primary customer of British shipyards, were increasingly buying their ships abroad, citing the UK’s high costs and long delivery times.

Attempts to remedy the situation

Investigations into potential problems in the shipbuilding industry started shortly into the post-war era. In 1948, following a British shipowner cancelling several orders with British yards due to “costs and delivery times,” the government stepped in to conduct analyses of the shipbuilding industry. One, produced by the Labour Party’s research arm, argued that “that new methods of construction, utilising welding and prefabrication, required a complete reconstruction of the yards, and that this could be best achieved via Government finance and assistance…It seems inevitable that a prosperous shipbuilding industry will require heavy expenditure and it is very doubtful whether the industry is willing and or able to undertake this.” The other, produced by the Shipbuilding Costs Committee (staffed largely by industry leaders), was a “’a very non-controversial report,’ which provided ‘no useful recommendations on which action could be taken.’” In light of the industry’s full postwar order books, the government opted not to take any action.

In the mid-1950s, the government examined the practices of British naval shipbuilding, and concluded that “there was a need for a wholesale modernisation of the shipyards in terms of layouts, plant and equipment particularly to increase the use of prefabrication.”

The return on capital employed and investment rates were criticised as poor and British costs were felt to be comparatively high in international terms. Restrictive practices were noted, but more worryingly there was a shortage of skilled labour in the industry, which was responsible for the British single-shift system, with consequently expensive overtime, compared with the double-shift system which was normal on the Continent and in Japan.

A 1957 report from the Working Party on the Transport of Oil From the Middle East similarly noted that the industry had been “sluggish in responding to the opportunities from expansion” and criticized its lack of investment (though it did note that some shipyards had begun some degree of modernization).

As the booming shipbuilding market turned at the end of the 1950s, these investigations grew more frequent and more worried. A 1959 Treasury report concluded the industry “is not competitive. It has not modernised its production methods and organisation so quickly or so thoroughly as its competitors. Its labour relations are poor, and its management, while improving, is not as good as it might be.” It was further “pessimistic over delivery dates and prices and concluded that the prospects of the industry becoming competitive could not be rated very high.”

This report was followed in 1960 by a Department of Scientific and Industrial Research report on the shipbuilding industry, which declared that the industry’s R&D efforts had been “woeful”:

…production control in the industry was primitive, the total effort devoted to research and development was insufficient, and almost no organised research had been applied to production and management problems with a view to improving the productivity of capital and labour and reducing costs.1

That same year, the head of the UK’s Shipbuilding Advisory Committee staged a high-profile resignation, stating that the excuses of the industry to avoid investigating its problems were “so frustrating that to continue serving the industry as chairman would be fruitless.” In response to the resignation, in 1961, the Advisory Committee released a report on the shipbuilding industry. However, other than arguing that credit facilities (lending to shipowners to make purchasing ships easier) should be expanded, the report gave few strong recommendations.

The Shipbuilding Advisory Committee report was followed by another government-commissioned report on why British shipowners were buying from foreign yards; the report concluded that the major reasons were “price; price and delivery date; price and credit facilities; guaranteed delivery dates; and the reluctance of British builders to install foreign-built engines.”

As the industry continued to struggle in the 1960s, the reports piled up even higher. A 1962 report on productivity commissioned by the British Ship Research Association noted “the underdeveloped nature of managerial hierarchies in the industry as a serious weakness and recommended a more systematic approach to production control”. A report by the British Ship Exports Association on the Norwegian market (traditionally one of Britain’s strongest ship export markets) noted that “Norwegian customers... have voiced a series of complaints, the principal of which. .. is that in addition to regarding us as unreliable over delivery, many are now saying that we cannot be trusted to honour contracts.” The author of the report noted that:

…every reported speech by a British shipbuilder in the Norwegian press usually comprised a list of excuses for poor performance, ranging from official and unofficial stoppages, shortages of labour, failings on the part of subcontractors, modernisation schemes not producing the anticipated results, to recently completed contracts having entailed substantial losses. The impression thus gained by the Norwegians, according to Holt, was of an industry where the shipbuilders had no control or responsibility over problems, and worse, had no ideas as to how to address the problems. (since 1918 147).

Accordingly, the UK’s share of Norwegian shipbuilding, its largest export market, fell from 48% in 1951 to 2.8% in 1965.

As reports documenting the UK’s shipbuilding troubles accumulated, things continued to look worse and worse for the shipbuilders. The market for ocean liners, once a major source of demand for British shipbuilders, was being threatened by the rise of commercial air travel. Transatlantic travel by air surpassed transatlantic ocean travel in 1957, and the ascendance of commercial jetliners further eroded the market. By 1969, passengers crossing the Atlantic by plane outnumbered maritime passengers 24 to 1. And the explosion of global trade in the 1950s and 60s was met not just with more ships, but with larger ships (such as Very Large Crude Carriers for transporting oil) which were cheaper to build and operate. The simple Liberty ship built in huge numbers by the US during the war was about 10,000 tons deadweight, but by the end of the 1950s Japan was building ships in excess of 100,000 tons deadweight.

Likewise, by the end of the 1960s Japanese shipyards were building drydocks with 400,000 tons capacity. By comparison, British shipyards, which had been built in an era of much smaller ships, had trouble accommodating these huge ships, in part due to lack of space for expansion. (Some space-constrained British yards attempted to get around their space constraints by building large ships in two halves, which were then stitched together in the water.) And as ships got larger, prefabricated construction methods got more advanced, utilizing massive gantry cranes to assemble ships out of huge pre-built blocks. Advances in prefabrication continued to drive down costs in the shipyards that implemented them. Between 1958 and 1964, the labor hours required to build a given amount of tonnage in a Japanese shipyard fell by 60%, and the amount of steel fell by 36%. Over the same period the UK’s share of global shipbuilding fell from 15% to 8%.

Throughout this period, major advances in ship technology were increasingly happened outside the UK. A history of UK shipbuilding noted that 13 of 15 major ship innovations introduced between 1800 and 1950 were first widely adopted in Britain. But of 14 major innovations introduced between 1950 and 1980, only three were first widely adopted in Britain.

Neither the government nor the British shipbuilding industry seemed willing to take bold steps to try to improve its fortunes. The Board of Trade stated in 1960 that there was little point to government intervention “until the prospects of the industry are very patently bad”. Despite the numerous government reports pointing out the various industry deficiencies, by 1963 the only government action that had been taken was the aforementioned expansion of credit facilities to shipowners. British shipbuilders remained convinced that a decline in the market was just around the corner and that the expensive shipyards of their competitors would become millstones. And despite the shipbuilding market shifting towards larger, more standardized ships sold at fixed prices, UK builders tried to stick with their tried-and-true strategy of ships tailor-built to the needs of British shipowners. But as British shipowners, who themselves made up an increasingly small fraction of global shipping (the UK’s share of global shipping tonnage fell from 45% in 1900 to 16% in 1960), increasingly took their business to foreign shipyards, British shipbuilders found that “the protective skin that tradition and convention gave to the home market has been split beyond repair”. By 1962, the bankruptcy of many UK shipbuilders had finally become “an alarming reality rather than an impending possibility”.

It wasn’t until after the 1964 elections, with a new Labour government, that more serious actions to rescue the shipbuilding industry began to be taken (possibly because the “vast majority of shipbuilding yards lay within Labour parliamentary seats”). In early 1965, a British group led by the Minister of Trade visited several Japanese shipyards, which were found to have lower costs, shorter delivery times, and higher productivity than British yards. Following this visit, the government instigated yet another investigation into the British shipbuilding industry. The resulting report (known as the Geddes report, after Reay Geddes, the head of the committee that produced it), enumerated a long list of problems of UK shipbuilders, including high costs (20% more than competitors on average), long delivery times, late deliveries, out of date infrastructure, poor labor relations, and poor management. Moreover, even at prices 20% higher than their competitors, British shipyards struggled to be profitable, with the report noting that “many of the orders now in hand will not be remunerative to cover costs”.

British shipyards’ traditional production methods, which demanded little in the way of management, meant that yards had few supervisors. The supervisors they did have had often worked their way up from the shop floor and had never received any business or management training. As a result, production planning and estimates of labor required were poor. While this may have been acceptable when vessels were custom-produced on a cost-plus basis, it made yards ill-equipped for a market where fixed-cost pricing was the norm. A history of British shipbuilding noted that “in an increasingly competitive industry British shipyards did not successfully perform the financial management tasks—marketing, budgeting and procurement--necessary to build vessels profitably.”

The Geddes report also noted that labor relations were abysmal, and strict adherence to labor demarcation rules (which themselves varied extensively from yard to yard) greatly hampered productivity. The labor demarcation problem was so severe that in some yards it literally took three different workers to change a lightbulb:

…a laborer (member of the Transport and General Workers Union) [to] carry the ladder to site, a rigger (member of the Amalgamated Society of Boilermakers, Shipwrights, Blacksmiths and Structural Workers Union) [to] erect it and place it in the proper position, and an electrician (member of the Electrical Trades Union) [to] actually remove the old bulb and screw in the new one. Production was often halted while waiting for a member of the appropriate union to arrive to perform the job reserved by agreement for them. (sunset 96)

The Geddes committee further argued that none of these issues could be fixed at the scale contemporary shipbuilders were operating at, and that a prerequisite for rescuing the industry was grouping existing shipbuilders together to give them the scale needed to be internationally competitive. The report recommended consolidation, and for a comparatively small amount of government financing (37.5 million pounds in grants and loans, and another 30 million in credit guarantees) to be awarded over the next four years to shipbuilders that consolidated and met a strict set of performance targets.

The post-Geddes industry

In 1967, the Shipbuilding Inquiry Act implementing the Geddes Report’s recommendations, was passed, and over the next several years, 27 major British shipbuilders were consolidated into 12 groups (though some of these “groups” were groups of just one). As shipyards consolidated, government financing began to flow: between 1967 and 1972 almost 160 million pounds (much more than had been recommended by the Geddes Report) were provided by the government to various shipbuilders, and the shipping board made recommendations for over a billion pounds worth of bank loan guarantees for British shipowners purchasing in British yards.

None of this helped stem the decline. By 1971, the government-backed British shipyards had achieved “no gains in competitiveness, no improvement in turnover, falling profitability and cash resources [that were] becoming rapidly inadequate.” Late deliveries continued to dog the shipbuilders: from 1967 to 1971 nearly 40% of British ships were 1 month late, and nearly 10% were six months late. With fixed-cost contracts, stiff penalties for late deliveries, and rapid inflation (over 20% from 1967 to 1971), late deliveries drastically eroded profitability, and much of the government funding actually went to writing off shipbuilders’ losses. Between 1967 and 1972 three major shipbuilders — Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (a post-Geddes amalgamation of several smaller builders), Cammell Laird, and Harland and Wolff (the company that built the Titanic, once the largest shipbuilder in the world) — were rescued from bankruptcy and became owned “wholly or in part by the British government”. In the early 1970s, the shipbuilding industry performed “even below the Geddes ‘worst case scenario”.

The industry’s failure to improve seems to be partly due to a lack of urgency on the shipbuilders part. A combination of factors (British pound devaluation, unexpectedly high enthusiasm for the credit offerings for British shipowners, the Suez canal closing) created enough demand for British ships in the late 1960s that the orderbooks swelled. While these orders were a small fraction of worldwide orders, the rise in demand was sufficient to dampen the urgency for reforming shipbuilding practices. In 1972, yet another report on the British shipbuilding industry (this one produced by Booz-Allen Hamilton), was released. It found that nearly every problem listed in the Geddes report had gotten worse:

This review of the U.K. shipbuilding industry is pessimistic about the general background situation, and critical of the industry in many areas. U.K. yards generally are under-capitalized and poorly managed; the industry has a poor reputation amongst its customers, particularly for delivery and labour relations; overseas competition has moved more rapidly to modernize and re-equip its facilities and is now better placed to face the forecast surplus of capacity which will exist for the remainder of the 1970’s

Even companies that had invested in the infrastructure they needed to compete in the modern shipbuilding world found themselves struggling. Harland and Wolff, for instance, had been “reconfigured in the 1960s to build tankers of up to 1 million deadweight tons”:

…it should have thrived during the 1967-73 large tanker boom. Instead, due to the typical British shipbuilding problems of high costs, low productivity, poor labor relations, and late delivery, it lost money even with a full order book.

The problem of money-losing contracts became so severe that some British shipbuilders found themselves paying owners to cancel contracts they were unable to build profitably.

With seemingly no way of returning the industry to commercial profitability, and already operating struggling shipbuilders directly, the government moved to full nationalization. In 1974, a Labour government was elected with promises to nationalize the industry, which eventually took place in 1977. The Aircraft and Shipbuilding Industries Act of 1977 created a new company, British Shipbuilders, encompassing 97% of Britain’s commercial shipbuilding capacity.2

But even nationalization did nothing to rescue the industry. After peaking in 1975, the worldwide shipbuilding market collapsed in the wake of the 1973 energy crisis. The shipbuilding industries in countries like Japan became desperate for new orders, and recent, subsidized entrants like South Korea, Taiwan and Brazil were hungry as well. In the face of such fierce competition, the new British Shipbuilders company wilted. Despite taking virtually any order that it could get, even at loss-making prices, the UK’s shipbuilding industry continued its inexorable decline. Between 1975 and 1985, the UK’s shipbuilding output declined by nearly 90%, and its share of the world market fell from 3.6% to less than 1%. British Shipbuilders began re-privatization in 1983 with the passage of the British Shipbuilders Act, and over the next several years most of those newly privatized yards would close. In 2024, the UK produced just 0.01% of the commercial ship tonnage built worldwide that year. In 2022 and 2023, the percentage was 0.

Conclusion

In his book on the decline of the British shipbuilding industry, Edward Lorenz argues that while British shipbuilders precipitated their own decline, their decisions were essentially rational, the product of the constraints that they were operating under at the time. A production system based heavily on leveraging skilled, union-trained labor, minimizing the need for expensive infrastructure or equipment and with a minimum of management overheads helped keep British costs low; the labor force could be scaled up and down depending on demand, and workers could easily move from yard to yard as the work required. This production system worked reasonably well for decades, and only truly began to unravel after WWII, when the shipbuilding market transformed technologically and transactionally, and began demanding much larger vessels, made from welded, block-construction, sold under fixed price contracts.

While British shipbuilders could have responded by enthusiastically embracing the new methods, they had learned from a lifetime of doing business in a wildly fluctuating market that investments in expensive new shipbuilding infrastructure or high-overhead production methods were risky. Their strategy of rapidly scaling their labor force depending on day-to-day needs had bred a deep distrust between management and labor, and created a strict demarcation system that was difficult to dislodge. Decades of urban development in port cities had made physical expansion of shipyards difficult. Uncertainty about whether transformation was truly needed, and the certainty of costly disruptions should they try, resulted in British shipbuilders sticking with their existing production methods as the rest of the world passed them by.

Moreover, globally the economic pressure to shift shipbuilding towards locations with lower labor costs was immense. Sweden modernized its operations far more effectively than the UK, and was one of the most efficient, capable shipbuilding countries in the world in the post-war era, but this didn’t stop the Swedish shipbuilding industry from being hollowed out in the face of competition from Asian producers. Similarly, Japan’s skill in shipbuilding hasn’t stopped it from losing ground to China in recent years.

There’s a telling bit in a book about the nationalized British Shipbuilders company called “Crossing the Bar”. At an international shipbuilders conference in London in 1983, a UK shipbuilder asked a Korean delegate why they were keeping their prices so low. The delegate responded that they weren’t worried about UK or European competition, or even Japanese competition: they were worried about China. Several decades on, Korea is now losing ground in the shipbuilding market to China too. So, it’s not clear if a much more vigorous British shipbuilding industry would have been all that much more successful in resisting its ultimate decline.

Nevertheless, the lack of motivation (rational or otherwise) of British shipbuilders to modernize their operations certainly did not help. Perhaps they would have ultimately lost out to low-cost Korean and Japanese builders anyway, but had they shared Japan’s “burning zeal” to make their industry competitive, they might have kept the wind in their sails longer.

The DSIR report was initially leaked to the media, and the final published version was stripped of much of its more trenchant criticism.

Harland and Wolff, despite then being owned by the British government, was left as an independent entity due to political concerns regarding Northern Ireland.

Your story describes strikingly well the downfall of Baldwin Locomotive Works. They, too, worked in an industry prone to the whiplash effect, and adapted with a capital-light system that relied on skilled labor in precarious employment. Their products had almost no standardization (and thus no interchangeability), compensated for via close relationships with local customers (Baldwin's biggest orders came from the PRR across town). And farly failures with experimental diesel prime movers meant they rejected the locomotives of the future until it was too late.

Thanks a lot - well prepared report with the interesting details