How Washington DC Got Its Metro

(Quick note: I’m working on a few projects about tunneling and tunnel boring machines. If you have experience with this sort of construction and would be willing to chat about it, send me an email at briancpotter@gmail.com)

There have been two main periods of subway (or “metro”) building in the US. The first was during the late 19th century and early 20th century, when Boston, New York, and Philadelphia all built subway systems1. But as Americans increasingly adopted the car during the early 20th century, enthusiasm for subways waned, and most cities (such as Los Angeles) opted to accommodate cars by expanding their road systems, rather than build mass transit systems.

The second period of subway building began in the 1960s. The downsides of the car and the infrastructure it required were becoming apparent, and some cities turned to subways to address the problems of traffic congestion. Metros built in this period include Atlanta’s MARTA in 1979, San Francisco’s BART, and Los Angeles’ Metro Rail2.

Of this second wave of metro building projects, the largest and most ambitious was Washington DC’s. When the initial system was finally completed in 2001, it extended for more than 100 miles, making it the largest post-war metro system. Today, the Washington metro is the second largest in the US after New York in terms of both length and weekly ridership.

How DC ended up with such an ambitious metro project is the subject of The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro by Zachary Schrag, which is adapted from Schrag’s PhD dissertation. The book details what it takes to build a rapid transit system in the US in a post-car world, and the challenges of building a massive infrastructure project in a country which has made that increasingly difficult.

The growth of DC

Despite being founded in 1791 and being the capital of the US, Washington DC grew slowly compared to many other American cities. By 1900, the DC metro area had a population of just 570,000, compared to 3.4 million in New York City and 1.7 million in Chicago. While the populations of New York and Chicago doubled over the following three decades, the Washington DC metro population increased by just 30%.

It wasn’t until World War II that DC began to grow substantially. The military bureaucracy began to expand, and in 1941 the government began construction on the Pentagon, the largest office building in the world, to house it. 4000 people were moving to the city each month, a rate which nearly doubled after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. As more people arrived, government offices “spilled into skating rinks, where the ice was melted and the floors covered with sawhorses and plywood desks…Secretaries could be seen sitting in front of bathroom sinks, their typewriters perched on boards laid across the basins, their steno pads propped on the toilet seats.” The Cold War, and the additional government bureaucracy it brought, meant that DC’s growth continued after the war. Between 1930-1960, the population of the DC metro area nearly tripled, from 860,000 to 2.3 million.

More people meant more cars, and more cars meant more traffic. By the 1950s, DC newspapers lamented that “motorists today spend from one to three hours of their off-job time in cars.” A survey by the National Capital Planning Commision projected that by 1980, there would be three times as much traffic on DC’s roads. To plan for Washington’s future transportation needs, the planning commission undertook the Mass Transportation Survey (MTS). Washington had a streetcar system at the time, but its declining ridership and poor finances made clear that such systems were on the way out. Most other cities were addressing their traffic problems by building more highways, but many people, including chairman of the planning commission Harland Bartholomew, were skeptical that highways alone could solve the city’s transit troubles. Prior to his appointment to the planning commission, Bartholomew had stated that “the automobile has disrupted and virtually exploded the city fully, as much as would an atomic bomb could its force be spent gradually,” and he firmly believed that rail still had a role to play in urban mass transit.

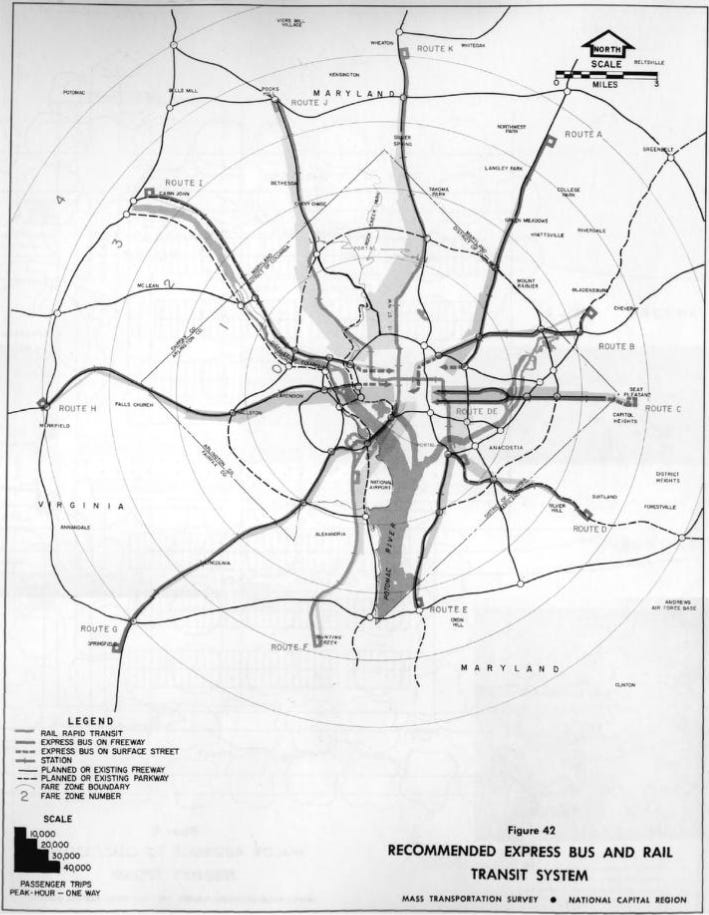

In 1959, the planning commission released the results of its study. It proposed a largely highway-based system, due in part to the 1956 Highway Act, which provided federal funding for highway construction and thus made them much cheaper for states to build, and in part because the planners lacked the time and funding for more detailed modeling of non-highway based systems. The plan did include two lines of rapid rail, totaling about 33 miles, but mass transit would mostly be provided by a series of new bus routes that would run on the new highways.

But public sentiment was beginning to turn against carving large freeways through urban areas, and the MTS plan drew an unexpected amount of criticism and debate. Anti-highway activists and citizen groups opposed the highways that would be built through existing neighborhoods, and one group of residents formed the “Committee to Oppose the Cross-Park Freeway” and showed up at hearings to protest. A DC district commissioner argued that “subways would be preferable” to cutting through the city with freeways.

From NCTA to WMATA

In response to the debate, Congress created the National Capital Transportation Agency (NCTA) in 1960 to further study the transit issue. That same year, John F. Kennedy was elected president, and many of his appointees to the NCTA were pro-mass transit and anti-freeway. Most notably, administrator of the agency C. Darwin Stolzenbach was strongly in favor of mass transit, and had argued against MTS freeway construction in 1958 as president of the Montgomery County Planning Association.

Under Stolzenbach, the NCTA reworked the MTS plan, and released its updated report in 1962. Unlike the MTS plan, NCTA’s plan heavily focused on rail transit. 89 miles of rail transit lines would connect 65 stations across the region, projected to cost $793 million (almost all of which would be paid back by fares). The number of highways, by contrast, was greatly reduced, and limited to places where their construction would have minimal impact on existing neighborhoods. Because the plan removed so many highways, and because most of the rail transit was planned to be above ground, avoiding excavation, the NCTA plan was projected to be cheaper than the MTS plan.

Once again, debate ensued. Critics argued that more highways would be better, given the amount of federal funding available for them, and that highways could move people more cheaply than rapid rail transit. Stolzenbach was accused of a “blind bias against highways.” Others argued in favor of building both transit and freeways, as cities like Atlanta were doing, giving “something for everybody.”

Most local officials largely stayed loyal to [the MTS] plan of something for everybody. Representative Broyhill of Virginia disputed the NCTA’s power to cancel highways, while representatives Carlton Sickles and Charles Mathias of Maryland and former D.C. commissioner McLaughlin argued that the region’s growth justified building transit and highways. Anne Wilkins, of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, emphasized that her county could not wait for rapid transit and wanted immediate construction of all of the highways and bridges in the 1959 plan…

But the NCTA plan was supported by Kennedy, who sent a letter to the DC government directing it to “assume the NCTA transit system would be built,” and reexamine the highway program. To rescue the rail plan from another round of studies, it was reworked into a smaller “bobtail” system, consisting of just 23 miles of rapid transit concentrated in the DC area. The previous plan, by contrast, had been envisioned as a much larger regional system. But when it went to Congress for a vote in 1963, the plan was overwhelmingly rejected, 276 to 78.

The fortunes of rail transit took a positive turn in 1964 when Congress passed the Urban Mass Transportation Act, allowing the use of federal highway funds for mass transit projects. In 1965, NCTA released a revised report of their recommendations, proposing essentially the pared-down bobtail system: 25 (up from 23) miles of rapid rail transit for the DC area, at a proposed cost of $431 million, of which fares would fund 65%. The plan passed Congress and was signed into law in September of 1965.

As the NCTA’s transit plans were being debated, regional governments debated who should be responsible for managing transit in the region. After several years of discussion and debate, a new agency was created in the style of New York’s Port Authority. The agency would be overseen by a board of six members, two each from Maryland, Virginia, and the city of DC. As part of the strategy for getting it approved, the new agency did not have the power to levy taxes. In fact, the compact that created it omitted any discussion of where transit funding would come from. This lack of a dedicated source of funding continues to haunt Metro today. But the compact’s strategy worked, and the proposal was passed in 1967, replacing the NCTA with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, or WMATA.

With the formation of a new interstate authority, NCTA’s transit plan was reworked once again to appeal to its new stakeholders:

Whereas the NCTA’s thrifty proposals had been largely designed to please Congress, the WMATA map would only become a transit system if it pleased enough voters in each suburban jurisdiction for them to pass necessary bond referenda. Such a map had to be, in the words of NCTA veteran Tom Deen, “big, bold, glamorous, fast, extensive, and, above all, [had to appear] to serve as much of the affected area as possible from the day the system first opens.” Given these requirements, Deen observed, “it’s easier to sell a billion dollar project than a hundred million dollar project.”

Because the system would have to be financed by bonds paid back through fare revenue, planners looked for ways to get the highest possible traffic volume with the lowest possible cost. The system would be built through high-traffic areas and make extensive use of existing railroad rights of way, which allowed for at-grade or elevated construction in lieu of expensive tunneling.

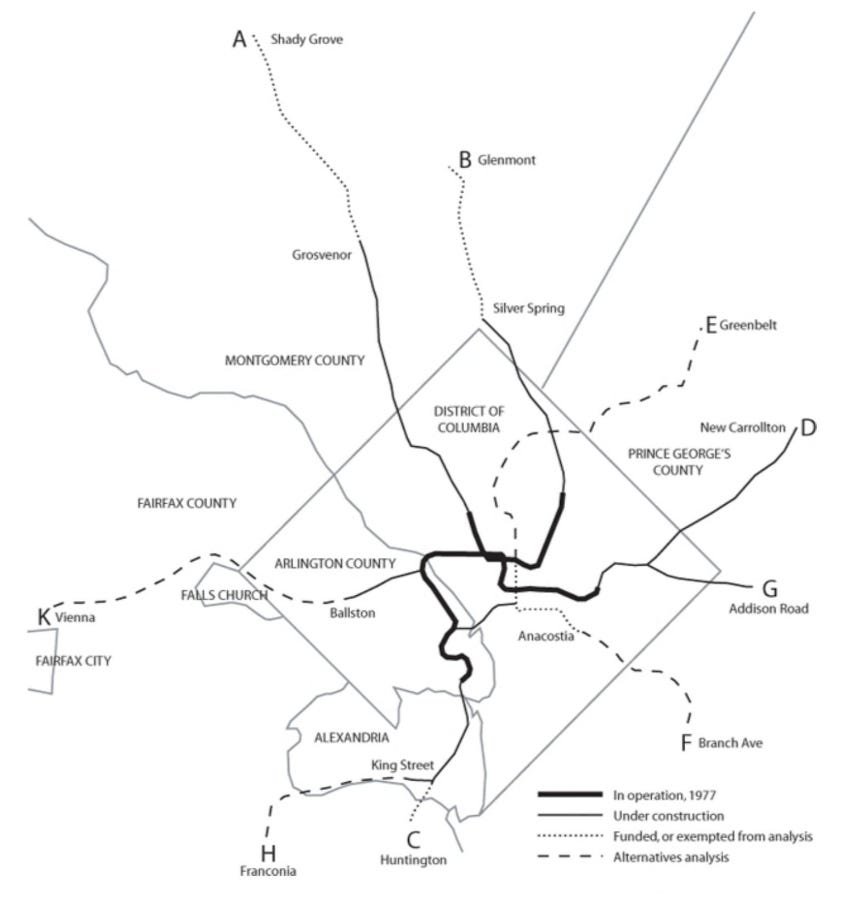

The 1967 WMATA transit plan, known as the Proposed Regional System (PRS), was the most ambitious plan yet, and included 95.6 miles of rail transit (later extended to 98 miles), compared to just 25 miles in the NCTA revised plan of 1965. When released officially in 1968, the system was projected to cost $1.8 billion in 1968 dollars, or $2.5 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars when completed in 1980, with the federal government contributing nearly half, $1.1 billion (the rest of the funds would come from a mix of local government contributions and fare revenue).

Natcher delays

Construction of the Metro would be delayed by Congressman William Natcher, who chaired the House Subcommittee on Appropriations for DC. Natcher was obsessed with procedure and protocol; he had memorized Robert’s Rules of Order in law school, and eventually claimed the Guinness world record for most consecutive roll-call and quorum votes cast (18,401). Natcher came to oppose Washington’s Metro because it represented a break in procedure:

Because the highways through the District had been mapped as part of the Interstate system, [Natcher] wanted to see them built. If those plans had been drawn up in error, that was of no more consequence than if he had misspelled his own name; what mattered was that once a decision was made, it was confirmed, and by the spring of 1966, Natcher wanted the highway program confirmed. In April he vented his disgust with what he called the “little pressure groups” opposing freeways.

To fight back against the anti-freeway groups, Natcher decided to withhold DC’s share of Metro funding. Since without DC’s share it would be impossible to get federal funds or to sell bonds, this had the effect of blocking all construction. WMATA was able to make some progress by getting Natcher to release funds for architecture and engineering, and it appeared the dispute had ended when Natcher finally released funds for construction in 1969, after the contracts for the highways were successfully awarded. But when freeway opponents scored a victory in 1970, Natcher responded by removing funding again in the 1971 budget. It was not until 1972 that Natcher finally capitulated and released the funds, a delay which added millions to the cost of the project.

Construction

The Washington Metro broke ground on December 9, 1969. While as much building as possible was done on existing rights of way, around half of the system would need to be built underground (US tunnels p185). Most tunnels were planned as “cut and cover” construction, which involves digging a large trench, building the tunnel structure within it, and then covering the trench up again. Cut and cover was at the time the cheapest way of building a subway, and had been used by most subways in the US, going back to New York in 1900. In places where cut and cover construction wouldn’t work, WMATA used other tunnel construction techniques, such as tunnel boring machines and “drill and blast” to excavate tunnels through soil and rock.

The downside of cut and cover was (and is) that it was incredibly disruptive, tearing up the street for years as construction took place. Knowing that the project could easily get bogged down in bureaucratic delays and debates from WMATA’s board, the manager of WMATA, Jackson Graham (a former brigadier general of the Corps of Engineers) adopted a cynical, realist strategy of project management:

…we want to get as much under construction as we possibly can, so it would cost more to cover it up than it would to finish it. Always we wanted to give the board…an unacceptable alternative, so that we would take them down the road we wanted to go. If we hadn’t done that, everything would have bogged down into bureaucratic debate, and quibbling, and so forth that goes on all the time.

Underground construction inevitably comes with its share of surprises, and the Washington Metro was no different. The builders tunneled through utility lines that weren’t where they’re projected to be, rock that was harder than expected, and buried coal bins that had been simply paved over when buildings switched to gas heat. Builders discovered that Washington’s old streetcar tracks, instead of being removed as required, had simply been paved over.

But people proved to be a bigger obstacle than difficult ground conditions. Other government agencies that had jurisdiction over areas of Metro construction often demanded plan changes. The Architect of the Capitol, George Stewart, wouldn’t allow a station to be built under the Capitol, requiring it to be moved a few blocks away. The University of Maryland rejected a proposed station on campus, forcing “a complicated redesign that later caused commotion in College Park.” WMATA had to coordinate its plans with those of the highway department, “weav[ing] their stations and tunnels around projected highway tunnels as well as existing utilities, sewers, and other underground hazards.”

The most difficult government agency proved to be the National Park Service. WMATA had originally planned many station entrances in the city’s downtown parks, like Farragut Square, McPherson Square, and the National Mall. But the NPS strongly objected to construction in the parks, and negotiations delayed construction by months. “In several cases,” notes Schrag, “WMATA had to promise not only to tidy up any mess but to leave parklands even better than they were prior to construction.” Approval for a station in Rock Creek Park, for instance, required WMATA to build the Park Police a new stable as “reparations” for the temporary disruption.

In other cases, getting Park Service approval required expensive redesigns that made the system less convenient. Schrag notes that a “planned bridge over Rock Creek became a tunnel underneath,” adding cost and forcing two stations to be built deeper, leaving them with “agonizingly slow, albeit majestic, escalators.” A planned station at Farragut Square that would have required moving the statue of David Farragut was rejected, resulting in two separate stations – Farragut North and Farragut West – just a few hundred feet apart.

Citizen frustrations were also a major source of difficulty. WMATA had promised that cut and cover would only disrupt traffic for 2-3 weeks until decking was in place to cover the excavation, but “funding delays, strikes, unmapped utilities and all the other problems with construction tended to stretch the disruption into months and years,” and turned streets into “dusty, muddy, noisy, crowded work sites.” WMATA was sued by a variety of citizen groups, including merchants whose buildings were to be demolished to make room for a new station, which resulted in the court ordering WMATA to hold public hearings for any decision that would affect private property. The system had not originally been designed to be wheelchair accessible, but a 1972 lawsuit mandated wheelchair accessibility, which required “hack[ing] elevator shafts through vaults of reinforced concrete” that had not been designed to accommodate them, and added an estimated $65 million to the cost of the project. Another lawsuit in 1973 resulted in WMATA agreeing to follow the requirements of the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This meant preparing separate environmental impact reports for each segment of the metro, which doubled the duration of the design phase and added an estimated $120 million to the cost of the system. And a citizens' lawsuit opposing a tunnel under Yuma Street won a series of injunctions that held up construction for 2 years, and was only resolved after WMATA “installed vastly more acoustical insulation than its engineers thought necessary, and minimized the disruption by digging vent shafts from the bottom up. When it needed to condemn a house to dig a shaft for emergency access, it paid the owner handsomely, then hid the top of the shaft with rows of azaleas, to be trimmed in perpetuity.”

Beyond lawsuits, citizen’s opposition forced other changes. A proposed station at Oklahoma Avenue was removed when residents protested the 1000-space parking lot that would be built in the neighborhood. At other stations, parking lot sizes were massively scaled back, resulting in parking lots a tenth the size of projected demand. Navigating interest group demands proved as difficult as tunneling through rock:

The peak years of Metro construction – 1973 to 1976 – highlighted the difficulties, and expense, of macro engineering in a crowded city. Every park, every historic structure, every sidewalk could become an obstacle. In one case, engineers had to shift the route to spare a single, historic oak tree. Amid fights over individual segments, broader debates highlighted the tensions inherent in any public transit authority.

Costs creep up

As obstacles continued to present themselves, the cost of the Metro continued to creep up. By 1970, the projected cost had reached $3 billion. By 1978, it had reached $6.8 billion. When WMATA’s initial system plan was finally completed in 2001, it cost $10 billion in nominal dollars, and closer to $20 billion if all expenditures were adjusted to 2001 dollars. It was called by some “the biggest boondoggle in the history of all mankind.”

Cost increases came from a variety of sources, though much was simple inflation. Between 1969 and 1975 alone, the cost of steel increased by 112%, the cost of asphalt increased by 242%, and the cost of labor increased almost 100% depending on the trade. Inflation not only drove up direct costs, but it also disrupted labor negotiations (which sometimes resulted in strikes), and made sales of revenue bonds more difficult. And as project delays mounted, inflation both increased costs and pushed back when revenues could start to be generated.

Unanticipated construction difficulties and accommodating various interest groups also drove up the cost “a few million dollars at a time”:

Burying the line near the stadium to meet neighbors’ demands added $18 million. Diving under a road, at the insistence of the Virginia Department of Highways, cost $8.5 million…The changes may have benefited the region as a whole, but they destroyed the engineers’ projections. As Jim Caywood of De Leuw, Cather [an engineering consulting firm on the project] put it, “there’s no way in this world that you can build a mammoth public works project such as Metro within a reasonable budget with all the outside influences. They won’t let you do it.”

Problems were exacerbated in 1973 when WMATA took over DC’s ailing bus system (renaming it “Metrobus”), which could only be saved from a death spiral of “declining ridership, decreasing fares, and widespread deterioration of service” by WMATA “pumping money into the system.” But WMATA was prevented from raising bus fares by court order, and by 1974 fares covered only half of the bus systems operating expenses, further straining Metro’s finances. In need of more funding, WMATA received another $875 million in 1976 from “federal highway transfer funds” – money taken from interstate highways that hadn’t been built in the face of public opposition.

But this extra funding wasn’t enough. By 1974, with 47 miles under construction, it was clear that Metro revenues would be insufficient to even pay operating expenses, much less capital costs. When the Metro first opened in 1976 with one line and five stations, it calculated that it was losing $75,000 dollars a day, or $27 million a year (a later analysis in 1978 suggested that by 1990, annual deficits would be nearly $200 million a year). And the calculated cost to finish it, $5.5 billion, was far more than the federal government was willing to pay.

But Metro proved hard to kill. The financing bust inspired another round of studies, but these tended to find that paring down the system based on what was already under construction was surprisingly difficult. The individual lines were “like colored wires on a B-movie time bomb: clip one and the whole thing explodes”:

Deleting any route would provoke the affected jurisdiction to demand tens of millions of dollars back from the Authority, with interest. It was easier for WMATA to keep borrowing, especially since each cut would only save a small percentage of the system cost.

Though the Metro was “besieged” with studies, no study could “offer a serious alternative to heavy rail as a mode of transit.” And the areas of service most tempting to cut were the same areas where freeways had been canceled in response to public protests. Removing those areas of the Metro would have a proportionately small impact on overall cost, and bringing back freeways would be both “politically unthinkable,” and even more expensive than finishing Metro.

Metro also proved to be popular. Polls showed citizens favored completing the 100-mile system, and by 1978 enough of the system was complete that commuters began to abandon their cars in favor of the metro. In 1979, when the second energy crisis drove gas prices up, transit ridership surged:

In 1979, Metro advocates in Congress were able to pass the Stark-Harris Bill, awarding an additional $1.7 billion in federal dollars, and having the federal government assume 2/3rds of WMATA’s bond debt. In 1990, WMATA would receive another $1.3 billion of federal dollars to complete what was now a 103 mile system.

Completion of the system

By 1985, the Metro was “largely complete,” though the Green Line would not open until 1991 and would not be complete until 2001. In 1988, the Metro won best public transit system in the US and Canada from the American Public Transit Association, and carried more people than any other US transit system except New Yorks. By 1994, it carried half a million people per day. Today, Metro operates 6 lines and 98 stations.

It was hoped that DC’s ambitious metro might be a blueprint for similar systems in other cities. But this didn’t come to pass: the DC metro remains by far the most ambitious post-war transit system in the US. Since it was built, the Metro has struggled. Ridership was below projected levels even before the pandemic, which reduced it even further. It has struggled with reliability and safety issues, and was nearly taken over by the Federal Transit Authority in 2016 after several passengers died in a derailment. Today, Metro has a huge budget shortfall thanks to post-pandemic ridership declines, and potentially risks the same sort of transit death spiral that it rescued the bus system from in the 1970s.

The Great Society Subway is available at Amazon and John Hopkins University Press

A subway system also began construction in Cincinnati, but work stopped in 1927 when the project ran out of funds, and it was never completed.

Two cities in North America built subways between these periods: Cleveland and Toronto.

Very interesting piece, thanks for writing. I grew up in the D.C. area and was always impressed by how a nation's capital could boast such a farkakte subway system.

Great piece! In the Construction section you have the reference "(US tunnels p185)". Could you add a link or more details to what that reference is referring to? I'm interested in learning more.