What Progress Has Icon Made on 3D-Printed Homes?

We last looked at 3D-printed buildings about three years ago. At the time, the technology was still nascent. Although there was a lot of enthusiasm, many efforts were academic, with little commercial deployment, and practitioners were experimenting with a wide range of approaches.

Since then, one company has emerged as the largest player in the 3D-printed building market in the US: Icon. It’s raised more than $400 million in venture capital, built more than 100 homes with 3D-printed walls, and partnered with NASA and the military on various 3D-printed building projects.

Icon recently presented at SXSW on the progress it’s made, which provides a good opportunity to take a closer look at the company and its technology. Icon has made some genuinely impressive progress, and they’re pushing the technology in the right direction. But, like any startup, it’s also exaggerating its success. In particular, it’s not as close to competitive with “conventional” construction as the team implies. Icon has made a lot of progress, but it still has a long way to go.

Icon's Cost

Icon has high hopes for its 3D printing technology, and while it stresses the many advantages of 3D-printed walls — they’re stronger, better insulated, and easier to make curved — the company clearly realizes that widespread adoption means bringing down the cost until it is competitive with or cheaper than conventional construction.

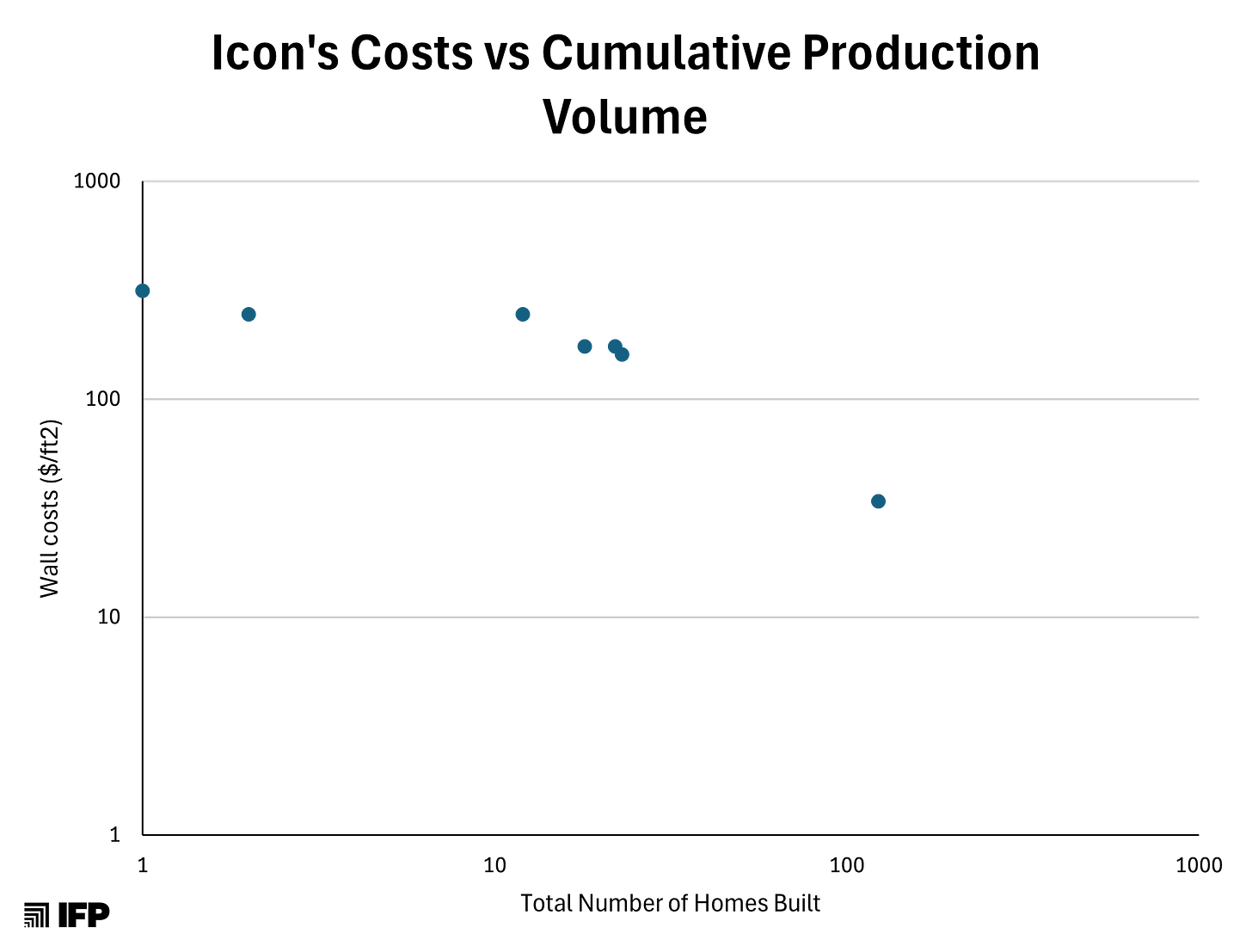

High costs have previously made me skeptical of 3D printing as a building technology. Some back-of-the-envelope calculations for Icon’s House Zero project suggested that the walls cost on the order of several hundred dollars per square foot to build, vastly more than conventional construction (Icon says its costs were $160 per square foot). However, on its project with Lennar in Texas, Icon claims it achieved a cost of $34 per square foot, a reduction of about 80% from House Zero.

This is an impressive reduction if we take that cost at face value (and I’d be very interested in learning more details). Icon appears to have come down the learning curve by building a lot more houses, improving its process and technology along the way. Including the costs of its other housing projects yields a cost reduction of 27% with every cumulative doubling, greater than the long-term rate of improvement in things like solar PV and wind turbines. Assuming its cost numbers are legitimate, and if it can maintain that rate (a giant if), Icon will achieve a cost of under $2 per square foot of wall by the 100,000th house.

However, Icon is also exaggerating its achievement. It claims that $34 per square foot beats conventional construction on cost. But this is not the case.

Icon’s claim is based on cost data from the same NAHB construction cost survey we looked at last week. By adding up the costs for the various systems that Icon’s walls replace — the vertical framing, the drywall, the exterior finish, and so on — Icon estimates that the walls on a 2,500 square foot home cost $115,000 on average. By then estimating the number of linear feet of wall in a home, they get an average cost of $35 per square foot of wall: higher than Icon’s costs. (See footnote for my attempts to reconstruct this calculation.)1 Thus, per the NAHB numbers, Icon is now cheaper than conventional construction for building walls.

There are a few things worth noting here. First, Icon’s costs are predicated on eliminating a lot of tasks that conventional construction requires: drywall, exterior finish, applying waterproofing, and so on. This is completely reasonable, but it does require leaving the 3D-printed structure exposed (though painted) in the final condition both on the interior and exterior. If you want a different finish, that’s doable, but it will add cost. It will be interesting to see how willing people are to accept this: people’s perceptions of exposed structure have historically been mixed. People like structural wood beams so much they’ll put in fake ones to achieve the look. Concrete blocks, on the other hand, look cheap and unfinished to most people.

Second, Icon is overestimating the cost of conventional construction. Icon implies that the NAHB cost survey is what the “average” home costs. But, as we noted last week, the NAHB cost survey is not the cost of an average home: it's based on a homebuilder survey that overweights boutique, luxury builders. The costs of a home per the NAHB survey, not including the lot, are about $100,000 greater than the average cost in the Census. NAHB’s costs of construction (including both hard costs and soft costs) work out to about $207 per square foot in 2022; per the Census, the actual national average in 2022 was $168 per square foot, and the median was $158 per square foot.

Icon is not comparing its costs to the average home, but to higher-end homes. This was not necessarily deliberate: I’ve also previously assumed that the NAHB survey data was a representative national average. But it means Icon is further from cost-competitiveness than an initial read of the numbers would suggest.

Furthermore, the NAHB cost categories that Icon uses include several things beyond the basic vertical framing that Icon is replacing. The framing line item, for instance, includes some costs for the roof as well. So even just going by the NAHB data, the costs per square foot of wall are lower than what Icon suggests.

We can get a better estimate of the costs to build a wall using conventional methods by using a construction estimating guide like RSMeans. Per RSMeans, the typical cost of a stucco exterior wall with 2x6s at 16” OC and R30 insulation is about $16 per square foot. Drywall will be another $1.60 per square foot, which gets us about $17.50 per square foot, or around half of what Icon suggests the average wall costs.

And this is for exterior walls. Construction of conventionally-framed interior partition walls will be even cheaper. RSMeans gives the cost of an interior 2x4 wall with drywall on each side as under $6 per square foot.

Even if we make fairly generous allowances for things like trim and baseboards (which these costs don’t include), we’re still far below Icon’s suggested average costs.

Icon doesn’t, as far as I know, break down the costs of its interior and exterior walls separately. But per photos, an exterior wall has one more wythe than interior walls, and will also require insulation and (possibly) more steel reinforcing. An exterior Icon wall might be roughly twice as expensive as an interior wall, depending how you spread the costs of things like printer setup and teardown time. It’s not clear if Icon’s $34 per square foot costs are for exterior walls (and interior walls are cheaper), or if that’s an average over all walls. If it's the latter, this suggests a cost of roughly $22 for an interior wall and $45 for an exterior wall.

So, while Icon has brought down the costs of its walls substantially, they're still more expensive than typical construction. Rather than being cheaper than average, based on Icon’s stated cost numbers I estimate that Icon's walls are between 2 and 4 times as expensive as the average conventionally framed wall.

Icon’s Technology Advances

In the same presentation, Icon introduces its next generation of 3D printers. Unlike its current 3D printer, which uses a gantry system, the next printer, dubbed “Phoenix,” uses a boom-mounted print-head. Not only does this give far more flexibility in print-head movement, but it gives Icon the ability to print second-story walls, which its current printer can’t do. Phoenix also includes some sort of steel wire extruder that can automatically place reinforcement, which was previously placed by hand.

Phoenix seems like a major step in the right direction. A major drawback to a gantry printer is the setup and teardown costs. Based on images from Icon’s project with Lennar, setting up its current printers requires what looks like setting a temporary printer foundation and building a rail system for them to travel on, which is obviously expensive and time-consuming.

A boom-mounted printer, by contrast, should have much less involved setup and teardown time (since the body itself doesn’t move), and its greater reach should enable it to do more printing without moving. Ideally, the printer can simply be wheeled into place, start printing, and then wheeled out when it's done.

A challenge for this sort of printer configuration is keeping the print head, which is at the end of a long, cantilevering boom, accurately placed. Simply making the boom rigid enough that the print head doesn’t move appreciably would be incredibly expensive. To address this, Icon has mounted compensating actuators and computer vision systems to the print head, which automatically correct its position. This technology is similar to what makes the Shaper Origin (a handheld CNC cutting tool that automatically compensates for arm movements) work, and is something I suggested might be a good idea several years ago, so I’m pleased to see it here. With Phoenix, Icon claims they’ll be able to achieve costs of $25 per square foot, another substantial reduction.

But once again, Icon is slightly exaggerating its achievements. Icon claims it will be able to use this printer to build not only the walls of a house, but the roof and foundations as well. These both seem technically possible, but I foresee limitations and challenges.

Icon’s plan for achieving 3D-printed roofs seems to require steeply sloping roofs. A 3D printer constructs things by placing a series of layers one on top of another, and there’s only so far you can shift the placement of a layer off the layer below while keeping the whole thing structurally stable. It’s possible to 3D-print roofs, but that will constrain the home layouts and shapes that are possible (for instance, wide open spaces without interior supports will likely require very tall roofs). Icon’s own renderings of their future offerings show a mix of 3D-printed and conventionally built roofs.

It’s not clear how Icon plans to achieve 3D-printed foundations. One option would be to print the foundations like any other structure, as a series of thin layers. Another option would be to use the printer like a conventional concrete pump, and pour a more fluid, liquid mix in a fashion similar to conventional construction.

The second method seems more promising to me. Printing seems ill-suited for placing the large concrete volumes that foundations require, and using printing to create a slab-on-grade seems challenging. In either case, there will still be substantial costs associated with foundation construction (such as excavation and ground compaction) that this system won’t handle.

More generally, the fundamental question with 3D-printed buildings is how you address all the parts of construction that can’t be handled by on-site printing: windows, doors, electrical wiring, HVAC, etc. A truly automated construction process must find a way to address these tasks as well.

Icon clearly recognizes this: its SXSW presentation calls 3D printing merely the first step in Icon’s larger push towards complete construction automation. It’s not clear to me if this was always their plan or if it’s revisionist history, but we have seen this approach elsewhere. Diamond Age, for instance, uses a gantry-mounted 3D printer which gets switched out for different robotic tools to handle other portions of the construction process. Icon is clearly trying to push automation farther into more tasks, but its trajectory is unclear. Ultimately, installing doors, windows, and wiring will require substantial advances in robotics, and while it’s possible Icon is working on these sorts of capabilities (I can imagine Phoenix forming a motion-stabilized platform that can then mount different robotic tools to it), we’ve seen little from Icon so far along these lines.

One other thing I’m curious about is what Icon’s project backlog looks like. Since its project with Lennar (first announced in November of 2022), the only project it’s announced is a planned development at a “Bohemian Campground Hotel” near Marfa, Texas, called El Cosmico. The El Cosmico homes, which range from 1,500 to 2,400 square feet, start at $900,000, not exactly homes for the masses. Even this project was announced more than a year ago: Icon’s website only says that "new projects will be revealed soon."

Conclusion

Icon has made impressive progress with its 3D-printed homes. Its costs appear to be falling substantially, its learning rate appears high, and its technology continues to improve. Though Icon exaggerates how competitive with conventional construction it is, it’s still shifted my opinion, and I'm less skeptical of 3D printing as a construction technology than before.

But the company still has a lot of challenges in front of it. Contra Icon, the company’s 3D-printed walls are still more expensive than conventional construction, and I have yet to see an obvious path or initiative that will push its technology to handle the rest of the construction process (which Icon itself agrees is the ultimate goal). It's also a little eyebrow-raising that Icon hasn’t announced anything resembling a “market rate” project in almost 18 months, or any new residential projects in a year. But Icon has raised a lot of money and doesn’t seem to be spending it frivolously, so hopefully it’ll be able to push forward.

NAHB cost data is below, with the items Icon’s system replaces highlighted.

This comes to $118,401 for a 2,561 square foot home. If we scale this down to a 2,500 square foot home, we get $115,580, approximately the number Icon uses.

For the wall length, 2,500 square feet on a one story home is equivalent to a square 50 feet by 50 feet. If we simplify and assume the interior is equivalent to four full-length interior walls, we get 400 linear feet of wall. Assuming an 8-foot high wall gets us 3,200 square feet of wall, which yields just under $36 per square foot. This is slightly different from Icon’s number, but it's close, so I assume their calculation looked something like this.

I attended the SXSW ICON event and know a few folks over there and I think this is a fair characterization of their progress thusfar. I was surprised to learn that their printer (at least the gantry version) is capable of doing horizontal reinforcement. They seemed to gloss over this in the presentation but it seemed big to me. However, for vertical reinforcement they are still printing pockets for a laborer to slot the rebar into, and then filling the pocket.

On the construction costs side, I think they vastly understate the gains from specialization and streamlined processes that have come from the standardization of the conventional American house building process. Trades like electrical, plumbing, painting, HVAC, and framed fixtures like widows seem like they could get easily double in labor costs, considering most tradesmen and contractors will be unfamiliar with the new wall system and might struggle to work around it's constraints.

I was also a bit disappointed to see that their home designer Vitruvius can't match up floorplans to concept/tour photos, although it seemed to be something people were quite positive about despite this. I'm most excited for the design marketplace and their plan to offer commissions (no indication how significant this might be yet) to home designers for every house printed.

The CEO seemed to want to push people to live more remotely in these types of printed communities, which seemed a bit like a cope one might resort to so as to avoid acknowledging that none of this tech addresses land cost, which is the real root of the housing crisis.

Overall positive outlook, but deserves a few grains of salt.

I'm a 3d printing enthusiast with a background in home construction. Finally, a subject which I might have something somewhat intelligent to say!

It's pretty amazing what kind of overhang angles you can get with traditional FDM 3d printing, but it's dependent on a lot of variables that require tweaking to get just right. The traditional rule of thumb is 45 degrees, but there's techniques that can get you 90 degrees! (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjGeBYOPmHA just one example technique) I wouldn't be surprised if with the right setup that you could 3d print a 6/12 or possibly a 4/12 roof. It would likely have a pretty ugly underside at those low angles.