How Common Is Accidental Invention?

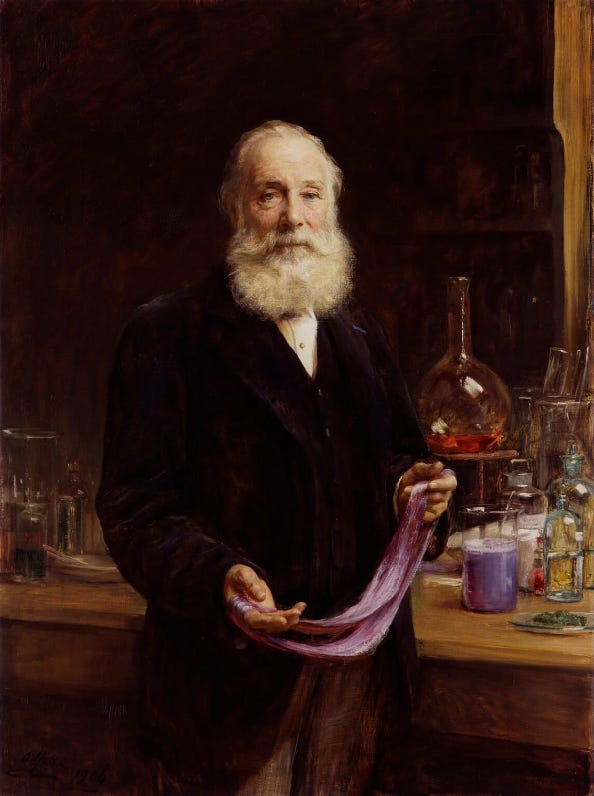

One of the most important inventions of the 19th century was mauve dye, the first synthetic aniline dye. First synthesized by William Perkin in 1856 out of coal tar, mauve led to the creation of an entire synthetic dye industry. Within a few years, many other aniline dyes, such as magenta, aniline blue, aniline yellow, and aniline black had been discovered, and large industrial operations had sprung up to manufacture them. The synthetic dye industry ultimately evolved into the industrial chemical industry in the late 19th century (using coal and coal-tar as its primary feedstock). Synthetic dye manufacturing was also the industry where the first industrial R&D labs appeared, formed to uncover new chemical knowledge in service of creating better and more efficient dyes and dyeing processes.

Beyond the industry that it spawned, mauve is notable for having been invented accidentally. Perkin stumbled upon mauve when trying to synthesize quinine, a treatment for malaria that was only obtainable from the bark of the cinchona tree. In one of his attempts, Perkin found that instead of the colorless quinine, he had created a reddish powder: further investigations of this unexpected creation resulted in a black residue that, when dissolved in alcohol, created a bright purple solution.

There are numerous other examples of accidental inventions. Famously, the process for vulcanizing rubber was discovered in 1839 by Charles Goodyear, after years of fruitless searching for a way to make rubber more durable, when he accidentally spilled a mixture of rubber, sulfur, and white lead on a hot stove. Gore-Tex was invented when a frustrated Robert Gore yanked heated rods of PTFE (teflon), inadvertently creating a material with millions of tiny pores. Titanium medical implants were the result of Robert Branemark’s accidental discovery that titanium would bond with bone when implanting titanium-bodied cameras into rabbits. Duco quick-drying automotive paint, champagne, penicillin — the list goes on.

Because I’m interested in the nature of technological progress, I wanted to get a sense of how common accidental invention is. So I turned once again to Wikipedia’s Timeline of Historic Inventions, which I previously used to estimate the rate of multiple invention. For each invention from 1800 to 1970 (190 inventions total), I looked to see if it could be characterized as “accidental.”

By “accidental,” I mean roughly, “the primary or major mechanism by which an invention works is created or discovered unintentionally.” The invention does not need to emerge fully formed, only the basic thing that makes it work. So Alexander Fleming’s chance discovery of penicillin would count as an accidental invention, even though turning Fleming’s observations into a working drug would take years of deliberate effort.

A deliberate search for something to solve a specific problem would not count as accidental, even if there was an element of chance in its ultimate discovery. So Edison testing hundreds of different filament materials for his incandescent light bulb until a suitable one was found would not count as accidental. By contrast, a deliberate search that resulted in something other than what was being searched for would count as accidental. For instance, I count Harry Brearley’s discovery of stainless steel, which he stumbled upon when he was searching for erosion-resistant steels to use in gun barrels, as accidental.

I also didn’t count someone accidentally or serendipitously getting the idea for an invention (the concept of “accidental” breaks down a bit when you’re talking about the origins of ideas, since we often don’t know why a particular idea pops into our heads). So Robert Gair seeing an accidentally cut paper bag, giving him the idea for a pre-cut cardboard box, would not count as accidental.

A challenge with determining whether an invention is accidental is that it requires having some idea of the inventor’s mental state, which may not have been recorded, or which may have been exaggerated by historical retellings. For instance, the invention of the safety pin by Walter Hunt is sometimes described as accidental, but pinning down (ha!) what was going through Hunt’s mind when inventing is very difficult. All we really seem to know is that it was invented in the span of three hours to pay off a debt to his draftsman, JR Chapin: Hunt agreed to sell the rights to any ideas he came up with based on twisting an old piece of wire. This could have been accidental, the product of randomly twisting the wire and ending up with a pin, but it need not have been. (I did not include the safety pin as an accidental invention.)

Accidental inventions

Altogether, of the 190 “major” inventions Wikipedia lists between 1800 and 1970, I counted 14 (just over 7%) that could be described as accidental.

This is a short enough list that we can enumerate each one. In addition to the four we’ve already mentioned (vulcanized rubber, mauve, stainless steel, and penicillin), the inventions are listed below:

The stethoscope was invented in 1816 when French physician Rene Laennec wanted to listen to the heartbeat of an overweight female patient, but was reluctant to put his ear on her chest. Remembering that sound could be heard through a solid object, Laennec rolled up a sheet of paper, placing one end against her chest and the other in his ear. Laennec was “surprised and elated to be able to hear the beating of her heart with far greater clearness than I ever had with direct application of my ear,” and realized that “this might become an indispensable method for studying, not only the beating of the heart, but all movements able of producing sound in the chest cavity.”

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) was first synthesized unintentionally by French chemist Henri Regnault in 1838 when a container containing vinyl chloride gas was exposed to sunlight, turning some of it into PVC. Regnault didn’t do anything with the material, and a patent for producing PVC wasn’t filed until 1913.

The critical breakthrough for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone came accidentally in 1875 when Bell was working on the harmonic telegraph (which would send multiple messages over a single wire by using different audio frequencies). From “Telephone”:

As usual, the thing would not work right; when Watson pressed the keys that set his transmitting reeds to vibrating at their carefully tuned pitches, one of the corresponding receiving reeds stubbornly did not respond. At Bell’s instruction, Watson began plucking the recalcitrant transmitting reed with his fingers. Suddenly he heard a shout from the other room, and then Bell burst in on him, demanding excitedly, “What did you do then? Don’t change anything!” Faintly, but distinctly, Bell had heard the sound of the reed, plugged at a moment when a too-tightly-adjusted contact screw had accidentally made the supposedly intermittent transmitter current into a steady current — and one modulated into a sound carrier by the air waves caused by Watson’s plucking.

X-rays were famously discovered accidentally by German physicist William Roentgen in 1895 when he was experimenting with cathode ray tubes1:

…Suddenly, about a yard from the tube, he saw a weak light that shimmered on a little bench he knew was located nearby. It was as though a ray of light or a faint spark from the induction coil had been reflected by a mirror. Not believing this possible, he passed another series of discharges through the tube, and again the same fluores- cence appeared, this time looking like faint green clouds… Highly excited, Roentgen lit a match and to his great surprise discovered that the source of the mysterious light was the little barium platinocyanide screen lying on the bench. He repeated the experiment again and again, each time moving the little screen farther away from the tube and each time getting the same result. There seemed to be only one explanation for the phenomenon. Evidently something emanated from the Hittorf-Crookes tube that produced an effect upon the fluorescent screen at a much greater distance than he had ever observed in his cathode ray experiments…

Polyethylene was first created in 1898 by German chemist Hans von Pechmann, when he found a “white waxy substance when investigating the decomposition reaction of diazomethane.” Nothing was done with the substance, and actual use of polyethylene would have to wait for another accidental invention of it, by ICI chemists in 1933.

Safety glass was invented by French artist Eduard Benedictus, after he noticed that a glass bottle stayed together after it fell from a shelf and broke in 1903. The bottle had originally contained a substance known as colloidon, an alcohol/ether solution of cellulose nitrate. The liquid inside the bottle had evaporated, leaving behind a “celluloidic enamel” which held the shards of broken glass together. Six years later, Benedictus created “triplex” safety glass, which consisted of two sheets of glass attached to a plastic celluloid core.

Czochralski crystal pulling, which creates large single crystals of material by slowly pulling them out of a molten pool, was invented in 1916 after Polish chemist Jan Czochralski absent mindedly dipped his fountain pen into a crucible of molten tin instead of an inkwell. When he pulled it out, a long thread of tin followed, which when cooled was found to be a single crystal.

The mechanism behind the microwave oven was famously stumbled upon accidentally in 1945 by Perry Spencer at Raytheon when he noticed a candy bar in his pocket was melted by a microwave radar he was working on.

The mechanism behind the silicon solar PV cell, light striking a p-n junction in a piece of silicon and creating an electrical current, was first created accidentally at Bell Labs in 1940.

Bell Labs engineer Russell Ohl noticed a silicon rod with a crack in it produced strange electrical behavior, including a surprisingly strong flow of electricity when exposed to light. Taking samples of the silicon, Ohl and his staff found that there were slight chemical differences on each side of the crack. The silicon rods had been cut from silicon ingots that were made in a furnace, and the ingot Ohl’s rod had been cut from had been cooled very slowly when taken out of the furnace to try and prevent cracking. As the ingot cooled, chemical impurities in the silicon had migrated — lighter impurities migrated to the top, while heavier impurities remained at the bottom. These different impurities were causing the photovoltaic phenomenon at the crack which separated the two regions. By chance, Ohl had stumbled across a p-n junction, a fundamental building block of semiconductor technology and the heart of modern solar cells.

Kevlar was invented in 1965 at Du Pont when Stephanie Kwolek, tasked with synthesizing new types of flame resistant polyamide fibers, stumbled upon some fibers with novel properties:

Unexpectedly, she discovered that under certain conditions, large numbers of polyamide molecules line up in parallel to form cloudy liquid crystalline solutions. Most researchers would have rejected the solution because it was fluid and cloudy rather than viscous and clear. But Kwolek took a chance and spun the solution into fibers more strong and stiff than had ever been created. This breakthrough opened up the possibilities for a host of new products resistant to tears, bullets, extreme temperatures, and other conditions.

Patterns of accidental invention

The most notable pattern at work here is that the majority of these inventions — 8 out of 14 — are chemical inventions. Accidental inventions make up around 17% of the 47 inventions between 1800 and 1970 I previously classified as chemical.2 This isn’t that surprising to me. Chemical phenomena are both highly opaque (meaning we’ll often be surprised by them), and require comparatively little deliberate effort to create. You might create a new, valuable chemical or chemical process just by mixing other chemicals together, or by exposing the right set of chemicals to the right set of conditions. Rubber vulcanization was invented when a mixture of chemicals spilled onto a hot stove, and Duco paint was invented when a batch of nitrocellulose and sodium acetate was left idle for a few days following a power failure. By contrast, it seems much harder to create a new, valuable machine by accident, in part because we can predict the behavior of physical objects much more readily than we can predict the behavior of chemicals: you can’t have an accident if you already know what’s going to happen. And while electrical phenomena are also opaque to human senses and not naturally intuitively predictable, it’s my sense that creating interesting combinations of them tends to require a lot of deliberate effort to create and shape moving electrical charges. But chemical reactions often happen on their own, without much in the way of human intervention.

The other notable pattern is that most accidental inventions (11 of the 14) were the product of deliberate research, or of attempts to invent something else. Mauve was invented when Perkin tried to synthesize quinine, the telephone breakthrough came when Bell and Watson were trying to build a harmonic telegraph, and X-rays were discovered when Roentgen was doing experiments with cathode ray tubes. Only three inventions — the stethoscope, safety glass, and the microwave — were the product of accidents outside the context of deliberate science or technology research and development. This probably also shouldn’t be surprising: it suggests the conditions for creating an accidental invention aren’t likely to be created in everyday life, but instead when trying to create or discover something new.

If we look at the frequency of accidental invention, it doesn’t seem to have changed much over time. On average a new one comes along every decade or so:

Conclusion

Accidental invention is in some ways the opposite of multiple invention. In the latter, an idea is obvious enough that multiple people have it; in the former, an idea is non-obvious enough that in a sense nobody has it at all. But apparently multiple invention is much more common — the rate of multiple invention for this set of inventions was close to 40%, compared to less than 8% accidental inventions.3

The major exception to this is with chemical inventions, where the rate of accidental invention ( around 17%) is much closer to the rate of multiple invention (33% for successes or near-successes). Evidently the nature of chemical phenomena — which are comparatively difficult to predict, but comparatively easy to create and manipulate — both makes accidental invention more likely, and multiple invention somewhat less likely.

I think it’s debatable whether it makes sense to classify X-rays as an “invention” or not, but it’s on the Wikipedia list so I’ve included it here.

Originally this was 46 chemical inventions, as safety glass was categorized as a mechanical one. But the nature of the discovery led me to re-categorize it as chemical.

Though accidental and multiple invention are not mutually exclusive. The telephone, for instance, is on both lists: Bell’s breakthrough was accidental, but both he and Elisha Gray had the idea for the telephone.

I'm not sure I understand the "hot blast iron smelting" entry - it sounds like Neilson was trying specifically to do something very much like what he ended up doing, not something unrelated.

The moral of the story is that planning and structured R&D funding matters. If 90% of inventions over this time period were intentional (people looking for a solution to that specific problem), it matters a lot.