The Long, Sad History of American Attempts to Build High-Speed Rail, Part II

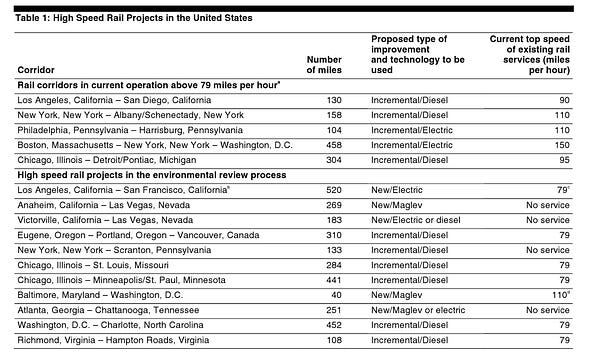

Last week, we looked at the early history of high-speed rail in the US. Though the US attempted to build its own high-speed rail routes soon after they debuted in Japan in 1964, these efforts were unsuccessful, outside of the popular-but-troubled Metroliner. By the end of the 1980s, high-speed passenger rail had been built or was under construction in countries around the world, with trains achieving speeds of up to 190 mph. In the US, by contrast, the Metroliner was achieving a maximum speed of just 120 mph, and other trains were limited to speeds of 80 mph.

Renewed federal efforts

Two major federal initiatives encouraged high-speed rail in the 1990s.

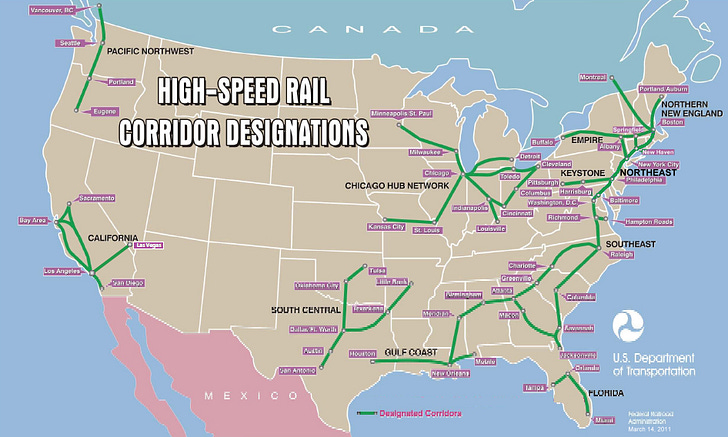

One was the creation of high-speed rail corridors. This began with the passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), which included a requirement to create at least five high-speed rail corridors, areas earmarked for high-speed rail development. The five initial corridors were designated in 1992, and since then several more have been added. However, the creation of corridors wasn’t paired with any specific plans to actually build high-speed rail routes, or any money for building them.

The other major federal initiative of the 1990s was funding the development of magnetic levitation (maglev) trains. Unlike conventional high-speed rail, which uses steel wheels on steel rails, maglev technology uses electromagnets to levitate the trains and propel them forward. Because it eliminates the friction between train and the track, maglev trains were expected to be much faster, and have much lower maintenance costs, than conventional steel-wheeled trains.

Maglev technology was first developed in the US in the 1960s, and maglev research programs were funded by the Federal Railroad Administration in the early 1970s. These efforts were abandoned in 1975, but research continued in Germany and Japan.1 In Germany, the first full-scale maglev systems were built in 1971, and by 1985 its Transrapid system was achieving speeds of 220 mph in tests.2 Japan’s first experimental maglev system was built in 1977, and in 1979 a maglev test vehicle had achieved speeds of over 320 mph.3

In the late 1980s, American interest in maglev was rekindled. The Maglev Technology Advisory Committee was formed to advise congress on maglev technology, and congress requests that the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) assess the feasibility of maglev trains. In 1990, the US established the National Maglev Initiative (NMI) to further study the possibility of maglev technology, and the ISTEA allocated $725 million to fund the development and construction of a maglev prototype (though it’s unclear if this money was ever actually spent). Many of the proposed high-speed rail systems in the US in the 1990s and 2000s were maglev trains.

More state attempts

As Congress turned its attention to high-speed rail, states continued to make their own attempts.

One such attempt came in 1989, when Texas passed the Texas High-Speed Rail Act, which created the Texas High-Speed Rail Authority (THSRA) to solicit proposals to build high-speed rail routes in the state. It ultimately received two bids, one from a company that aimed to bring France’s TGV system to the US (Texas TGV) and one that would use German’s InterCity Express (ICE) trains (Texas FasTrac). In 1991, the Texas TGV plan was selected, for a system that would connect Dallas, Houston and San Antonio.

The trajectory of Texas TGV in many ways paralleled the earlier attempt to build high-speed rail in California, as both projects struggled to navigate local opposition and burdensome environmental review processes. Though Texas TGV would receive no public funding, it required new regulations from the Federal Railroad Administration (a “major” federal action), and therefore needed to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act by completing an environmental impact statement. In the process of creating the statement, 39 public meetings were held (one for each county the project would run through). Those meetings became a vehicle for grassroots opposition:

“Opponents of the project used these scoping meetings…as opportunities to spread their own message.” Almost 50 percent of the speakers at scoping meetings were from outside the county in which the scoping meeting was held…A resident of Zorn, Texas, testified at one hearing that, in his community, “there is not one person for it. We don’t understand it, we don’t want it.” But this response was relatively calm compared to “the Lockhart meeting [where] feelings were so impassioned that threats of violence were made and the executive director of THSRA told me he was glad the police were present.” A group calling itself DERAIL (Demanding Ethics, Responsibility, and Accountability in Legislation) began lobbying against the Texas TGV project, publishing a pamphlet entitled A Ticket to Nowhere that attacked the Texas TGV as a $6.8 billion boondoggle.4

In addition to resident protests, Texas TGV also faced opposition from Southwest Airlines, a Texas-based airline. Worried about potential loss of revenue should a high-speed rail system be built, Southwest filed three lawsuits against the Texas TGV project, worked to prevent federal subsidies for the project, and threatened to withdraw service from San Antonio if the city provided any assistance for the project.

As with the Californian attempt at high-speed rail, the project was ultimately unable to secure private investment (probably in part due to the significant grassroots and legal opposition, and lack of federal support). In 1994, Texas TGV failed to raise $170 million to fund the project, the THSRA revoked its franchise, and the THSRA was abolished the following year.

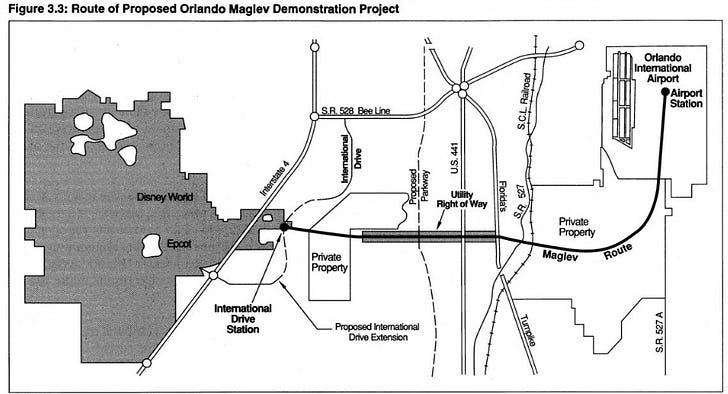

While Texas TGV struggled, a series of attempts to build high-speed rail were taking place in Florida. In 1988, Florida passed the Magnetic Levitation Demonstration Act, and in 1991, the governor approved the construction of a demonstration maglev route, based on German Transrapid technology, between Orlando Airport and Disney World. But by 2000 this project would be on hold.5

Florida also saw several attempts to build more conventional high-speed rail. In 1992, Florida’s Legislature amended its 1984 High-Speed Rail Act, and indicated it was willing to spend $70 million per year for up to 40 years to fund high-speed rail development. By 1995, the state had received five proposals to construct high-speed rail systems connecting Miami, Orlando, and Tampa, ultimately selecting the Florida Overland Express (FOX) project to proceed. FOX faced many of the same hurdles as previous high-speed rail projects, such as grassroots opposition and ridership figures that were criticized as overly optimistic, and it was killed by newly-elected governor Jeb Bush in 1999 in one of his first acts in office. Bush portrayed the project as “the kind of big government boondoggle that he had been elected to prevent.”6 Bush would continue to oppose Florida high-speed rail in 2000, even after voters passed a constitutional amendment to set up high-speed rail service between the state's five largest metros. Bush and the state legislature refused to release the funds for the project, and it was killed in 2004 when the constitutional amendment was repealed by popular vote.

There were also further attempts in California. In 1988, the California Nevada Super Speed Train Commission was formed to build a Maglev line between Las Vegas and Orange County, California using German Transrapid technology. The project managed to gain the support of “the region’s Congressional representatives…as well as the cities, counties, and regional planning organizations.” It’s not 100% clear what happened with this project: It continued on until the 2000s, beginning the environmental review process in 2004, but apparently that process was never completed (possibly due to lack of funding). By 2012 the project was dead. At the same time, a high-speed rail route between San Francisco and Los Angeles began to move forward. In 1996 the California High-Speed Rail Authority was created, and it prepared a ballot measure that would fund the project.

In addition to the California-Nevada maglev, another project between Las Vegas and Southern California began in 2005, the DesertXpress. This project was dependent on a federal loan which never materialized due to “Buy American” provisions, but the project has since been reconstituted as Brightline West, and is planned to begin operating in 2027.

There were also a series of projects in the Northeast in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 1990, Maglev Inc was formed to build an experimental maglev line in Pennsylvania between Pittsburgh Airport, downtown Pittsburgh, and Greensburg, with the ultimate goal of manufacturing and exporting maglev trains around the world. Like the California-Nevada maglev line, this project limped along for years, completing its environmental review process in 2010 only to fold in 2012 after failing to secure funding.

The Pennsylvania maglev demonstration project was funded by the Maglev Deployment Program, a Federal Railroad Association program created by the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) in 19987. The Maglev Deployment Program authorized $950 million (which has never been allocated) for the construction of a demonstration maglev project, funded preliminary studies for seven projects, and ultimately selected two for further development. One was the Pittsburgh Airport project, and the other was a project to connect Baltimore and Washington with a maglev route. This project, today called Northeast Maglev, is still in development, with a tentative plan to complete its environmental impact statement by 2024 and operate by 2030.

The one bright spot for US high-speed rail in the 90s and early 2000s was also in the northeast. In the early 90s, Amtrak began to explore more advanced train technology, testing high-speed Swedish X2000 tilting trains and German ICE trains. With tilting trains, higher speeds could be achieved without needing to construct special routes with shallow curves. In 2000 Amtrak began to run the Acela Express between Boston and Washington DC, using high-performance tilting trains that could achieve speeds of 150 mph. The Acela cut the time from Boston to New York from 5 hours to around 3.5 hours, and in 2002 Amtrak started a 2 hour 28 minute Acela service from New York to Washington, finally beating the time that the Metroliner had achieved in 1969.

Apart from the Acela, by the late 2000s America seemed no closer to achieving high-speed rail routes than it had in the 1980s. But in the wake of the financial crisis, high-speed rail development got another federal boost in the form of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act, which (among other things) authorized funding for the development of high-speed rail along designated corridors, and ARRA, which provided up to $8 billion (later expanded to $13 billion) for high-speed rail investment.8

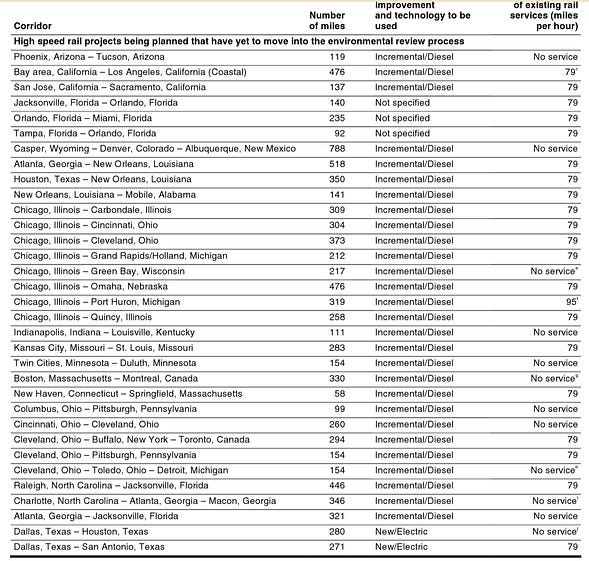

This funding triggered another round of proposed high-speed rail projects (more than 278 applications were received), many of which are still in development in some form or another. The projects which received the largest share of federal funding were California’s route between Los Angeles and San Francisco (which had finally begun after voters approved a $10 billion bond issue in 2008) and a Florida route between Tampa and Orlando. The rest of the funding was spread “thinly across thirty-one states and the US capital,”9 and many of the funded projects were incremental upgrades for diesel-powered routes, rather than true high-speed rail.

California’s High-Speed rail is of course under construction today, though the project has proceeded slowly. Florida’s Orlando-Tampa line was canceled in a similar manner to the previous line, when incoming governor Rick Scott announced he would reject any federal funds for the project shortly after taking office, citing it as “far too costly for taxpayers.”10 Florida would finally get its “high-speed rail” (using the term loosely) with the Brightline, which began work in 2012 and started service in 2018.

Other true high-speed rail projects that still exist in some form are a proposed Atlanta-Chattanooga route and the Texas Central Railway (TCR), which would connect Houston and Dallas using Japanese Shinkansen technology. The TCR is still limping along, but has faced rising projected costs and numerous lawsuits, and the board of directors and the CEO all resigned last year. The Atlanta-Chattanooga line has completed its environmental impact statement but doesn’t seem to have made any progress.

Conclusion

An enormous number of US high-speed rail routes have been proposed. And this only lists the ones that have made it far enough to have concrete plans and secure some amount of funding, and were in some sense “real.” Innumerable others never made it beyond the conceptual study phase. Putting aside for the moment the question of whether we should be building high-speed rail, why have these projects consistently failed?

One issue that comes up repeatedly is difficulty in acquiring funding. There’s no dedicated source of federal funding for projects, which makes them vulnerable to changes in federal or state budgets. Voters are often reluctant to fund the projects directly with ballot measures or bond issues, and private investors have likewise often been unwilling to back projects. Funding issues are exacerbated by the fact that, even in best-case scenarios, high-speed rail lines are very expensive to build, and frequently exceed their initial cost estimates.

Funding is a perennial issue because it's very difficult for a high-speed rail line to pay for itself. Around the world, only two high-speed rail lines (Paris-Lyon and Tokyo-Osaka) earn enough money from fares to pay back their infrastructure costs and operating costs, and many can’t even cover their operating costs without government assistance.

Even aside from funding, high-speed rail projects are very difficult to plan and build. Like any large-scale, horizontal infrastructure project, they’re often opposed by residents and local governments, which can use the politics of delay to slow down the project. Public opposition also makes it difficult to assemble land parcels necessary for the project. Land acquisition problems have plagued both California’s high-speed rail and the Texas Central Railway (Brightline notably avoided this issue by using existing transportation corridors). The political calculus of getting project approval often means that route layout is compromised, adding expenses to the project (something that is seen in other high-speed rail routes around the world, such as Germany).

And the US in general has been a difficult environment for passenger rail. In The Second Age of Rail, Hughes notes that one of the chief difficulties of building high-speed rail in the US is a “deep hostility to inter-city passenger trains at all political levels,” and citizens who have “little or no concept of inter-city rail travel.” The supporting infrastructure (such as local commuter trains) seldom exists in the US, and car travel is much cheaper in the US than in many other countries, making high-speed rail comparatively less competitive. Existing transportation interests, such as airlines and freight rail (which generally own existing tracks) will often oppose it or “regard it as a nuisance.”

None of these difficulties seem to be easing over time, and the struggles of California’s high-speed rail seems like a massive cautionary tale for future projects. It’s hard to see the situation of American high-speed rail’s prospects improving.

Despite decades of tests, Transrapid was never commercially deployed in Germany (though it was used for the only commercial maglev deployment in China). The developers continued to promote it, but its fortunes turned when a test vehicle collided with another train in 2006, killing 23 people and injuring 10 more. The test system was dismantled in 2013.

Like the German Transrapid, Japanese maglev has been in development for many decades but hasn’t yet seen commercial deployment.

Perl 2002

It would later be revived by a different company, and ultimately canceled in 2015.

Perl 2002

The TEA-21 also resulted in the creation of several more high-speed rail corridors.

Though apparently this included anything above 90 mph.

Hughes 2015

Hughes 2015

Thank you for providing these in-depth articles. History is instructive as it reminds us that the "good ideas" of today may not be original and we ought to consider and learn why the same "good ideas" did not work in previous generations.

An underappreciated aspect of transportation solutions is the competition between roads and rail and air and water is constantly changing as technology provides new options and consumer preferences adapt. The "National Road" is commemorated in Ellicott City Maryland. One of the information boards talks about the competition between the railroad and the road. In the 19th century, innovations with railroad gave the upper hand to the trains.

"Noisy, dirty, and at first, unreliable, the railroad soon gained the upper hand. By 1840, a stage coach trip to Cumberland on the National Pike cost $9 and took twenty hours. The same trip on the B & O cost $7 and took ten. John H. B. Latrobe summed it up best when he wrote, “That solitary horseman who comes down [the National Road] at a trot that dislocates half the bones in his body, and sends his saddle bags with grievous flapping is one of the few who still prefers its glow and dust to the shade and velocity of travel on the iron avenue to the west.” While it was so important for the first decades of the 1800s, the National Road was doomed." https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=720

Today, the Patapsco Valley tracks carry coal on train cars from Appalachia to the port in Baltimore, but there is no passenger rail service. Instead, many thousands of cars each day drive the "National Road" and its derivative freeways to travel between homes and towns west of Baltimore to the city and back.

>Around the world, only two high-speed rail lines (Paris-Lyon and Tokyo-Osaka) earn enough money from fares to pay back their infrastructure costs and operating costs, and many can’t even cover their operating costs without government assistance.

Do you have a source for this? If I remember correctly, the EU does not allow subsidies to long-distance rail and member states have gotten into trouble for violating this in the past.