What Makes Housing So Expensive?

Buying a home is by far the largest purchase most of us will make, and paying the rent or mortgage will be our largest monthly expense. In the post-pandemic home-buying boom, the median sale price of a new home peaked at almost $500,000 dollars, just under seven times the median household annual income that year (though it has since fallen). Most new homebuyers will pay around 30% of their income on their mortgage, and the median renter in the bottom quintile of income spends 60% of their income on rent.

Because of the enormous costs of housing, it's worth understanding where, specifically, those costs come from, and what sort of interventions would be needed to reduce these costs. Discussions of housing policy often focus on issues of zoning, regulation, and other supply restrictions which manifest as increased land prices, but for most American housing, the largest cost comes from building the physical structure itself. However, in dense urban areas — the places where building new housing is arguably most important — this changes, and high land prices driven by regulatory restrictions become the dominant factor.

People concerned about building more housing are right to pay attention to zoning and land use rules: over 100 million Americans live in places where most of the cost of residential property comes from the land itself. But they should not neglect the physical costs of building homes, which are overall more important. Unfortunately, as we’ll see, reducing these physical costs is far from straightforward.

The costs of a single-family home

We’ll look at housing costs chiefly through the lens of single-family homes, for a few reasons. Most housing in the US consists of single-family homes, so the costs of building them largely map to US housing costs generally. There’s also a large amount of data available on single-family home construction that doesn’t exist (or is much less accessible) for other types of housing. And most multi-family apartment buildings in the US will be built using the same basic technology, light-framed wood, used to build single-family homes, so much of what we learn about single-family costs, particularly on the construction side, will apply to multi-family apartments as well.

We can start by looking at the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) construction cost survey. This survey is periodically sent out by the NAHB to several thousand home builders. It divides home building into several dozen separate activities (framing, plumbing fixtures, drywall, etc.) and asks home builders about their typical costs for each task. Note that while the survey is based on the average costs of thousands of different home builders, it does not represent the costs of an average home. Because every home builder gets equal weight in the survey, it overweighs the costs from boutique, luxury home builders (who might build just a few homes a year) and underweighs larger volume economy builders (who might build hundreds or thousands of homes a year). The “average” home cost given by the survey is almost $100,000 higher than the average home cost indicated by the Census. But while absolute costs won’t necessarily be representative, I expect the relative proportions devoted to each task to vary less between the low and high ends of the market (and we’ll do a bit of checking to be sure this is the case).

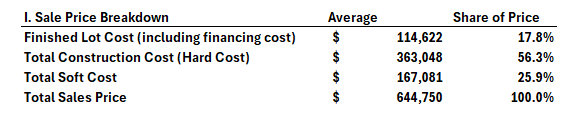

We can divide the costs of a new home into roughly three buckets: “hard costs” (physically constructing the home), “soft costs” (design, administration, marketing, and other non-physical construction costs), and the costs of land. Per the NAHB, on average hard costs are about 56% of the total costs, soft costs (including builder profits) are about 25%, and land costs are about 18%.

Let’s take a deeper look at each one of these items.

Hard costs

Hard costs are inherent to constructing the building itself: digging and pouring the foundations, building the framing, installing the HVAC system, and so on. Hard costs make up the majority of the costs of a new home, which is why I spend so much time thinking and writing about construction productivity. The NAHB survey breaks hard costs further down into the specific tasks they’re associated with, shown below:1

The above graph is color-coded: green is the structural framing, blue is exterior finishes (including doors and windows), orange is services (electrical, HVAC, etc.), red is interior finishes and appliances, dark gray is foundations and light gray is outdoor work and landscaping. And if we look at a similar breakdown of tasks given by the Craftsman Construction Estimator, we see a broadly similar division.2

A few things stand out here. One, outside of a few large line items (the framing and the foundations, which together are almost 30% of the cost), in general no single cost dominates. Construction consists of many separate tasks done by separate trades, each making up a relatively small fraction of the overall cost.3

This isn’t unique to construction: we could construct a similar cost breakdown for manufacturing a car. And neither is subcontracting the work out to many separate trades. Ford uses more than 1,400 Tier 1 suppliers to supply parts and components. What is different about construction is the level of coordination that takes place: whereas in a car everything is carefully designed to tightly integrate together, in housing construction the work can be done (and often is) with surprisingly little coordination between the various trades. Even something as seemingly basic as getting subcontractors together at the beginning of the design process to come up with a coordinated design is a very unusual practice in home construction. This style of work organization reduces upfront cost required, and allows homes to be built with an unusually inexpensive design process compared to other products, but it also means that innovation is risky, and new products tend to be evolutionary ones that don’t change the overall construction process.

But this doesn’t mean that innovation doesn’t take place. For each of these tasks there is constant industry effort to try and improve them. In some cases, those efforts are successful, as with PEX piping replacing copper piping. In other cases, industry hasn’t made great strides. Framing technology, for instance, has changed comparatively little, despite many attempts to develop alternative framing systems.

Something else that stands out is the relatively large fraction of tasks that have an aesthetic component. Interior and exterior finishes combined — trim, drywall, exterior finishes, and so on — make up more than a third of the hard costs of a new home. These costs can also be difficult to reduce, because people’s preferences about how various parts of the house look or feel can be surprisingly strong, and constrain the use of new systems. Luxury vinyl tile or synthetic stone bathroom panels are probably superior to hardwood floors and ceramic tile from the perspective of functionality, but people’s preferences for more “natural” materials are hard to displace. Similarly, the flimsiness and visible joints of inexpensive drywall substitutes like vinyl on gypsum makes it hard to replace drywall outside of the low end of the market.

We can further break down the hard costs of construction by separating tasks into the cost of materials and the cost of labor. NAHB doesn’t provide this data, but Craftsman’s National Construction Estimator does:

We see that hard costs are roughly 50/50 split between materials and labor (and we saw something similar when we looked at how the cost of individual construction tasks has changed over time). This is yet another thing that makes reducing construction costs difficult. A large fraction of hard costs are due to the cost of materials, and there’s no obvious path for making these cheaper. Bulk building materials are already mass-produced in factories, and are among the cheapest materials civilization is capable of producing. As we’ve noted previously, modern buildings are fairly materially efficient, and there’s no obvious path for using substantially fewer materials that doesn’t come with significant tradeoffs.

One final thing worth noting about hard costs is that they can vary significantly from place to place. The Turner International Construction Market Survey gives a wide range of costs for things such as electrical work or structural steel in various US cities. An electrician that costs $78 per hour to hire in Houston might cost almost $170 to hire in New York City. Similarly, construction estimating company RSMeans gives a “city cost index” to adjust costs for local conditions, which can shift “average” labor costs by plus or minus 50% or more.

So overall, the hard costs of construction — the costs associated with putting up the actual, physical building — are the largest and most important cost of a new home. But they’re also the hardest things to improve, and there’s no simple or obvious path for doing so.

Soft costs

Soft costs, as we’ve noted, include financing, permits, inspections, design work, and other administrative tasks not directly associated with building the physical home. According to the NAHB survey, soft costs make up the second largest portion of costs of a new home.

Looking at a line item breakdown once again shows the difficulty of reducing costs, and the lack of straightforward paths for improvement. For instance, a common complaint about construction (and one I’ve made elsewhere) is the amount of time it takes to build a building, and how construction seems to be getting slower over time. Because of this, people are often optimistic about technologies like prefabrication that allow for faster construction, and the potential money such rapid construction would save.

But per the NAHB survey, construction financing cost, one of the main avenues of potential savings from accelerated construction, is fairly low, just 1.9% of the total cost of a new home.4 Depending on the technology chosen, speeding up construction might have surprisingly little impact on this. Prefabrication, for instance, can reduce on-site construction time, but using prefabrication often requires the fabricator to begin work months beforehand. If you need to make a downpayment to the fabricator before they start work, you might not have reduced your financing costs at all, merely shifted when they take place.

Likewise, soft costs like design work, permits, and inspections are fairly small proportions of overall costs. (We also found fairly small costs associated with things like OSHA regulations.) Builders profit is somewhat high (above 10% of the costs of a new home according to the NAHB), but this is probably in part skewed by the sample, which overweights smaller, luxury builders. The National Construction Estimator (whose estimates are roughly in line with Census cost data, and thus probably a good average) suggests a much more modest 5% builders profit. Sales commission is also on the higher side, though this may be on the cusp of being reduced. While real estate startups like Zillow, Redfin and Trulia have not managed to dislodge realtors from the homebuying process, a recent court ruling is expected to greatly reduce realtor fees.

As with hard costs, so with soft costs: No one dominant item, and few obvious paths for cost reduction.

Land costs

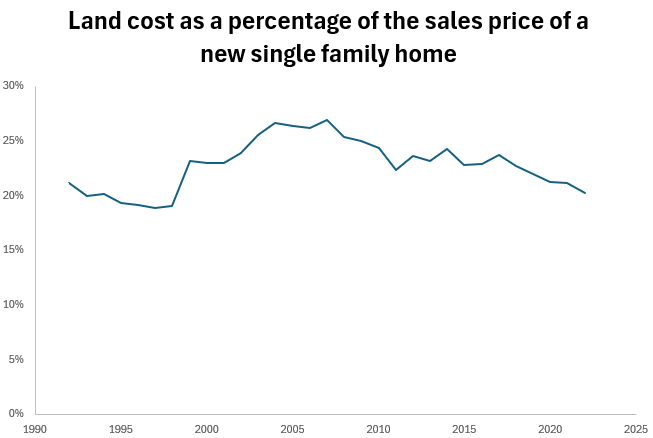

The third major cost of building a new house is the cost of the land itself. Given how prominent regulatory restrictions on housing are in online discourse (zoning, NIMBY vs YIMBY, and so on), I think many people would be surprised that land only makes up around 20% of the cost of a new home. But we can confirm this with Census data, which shows that over the last 30 years, the fraction of the price of a new single-family home that’s due to the cost of land has remained remarkably steady, generally hovering between 20 and 25% of the total cost. (“20% of your costs should be for the property itself” is also a common rule of thumb among homebuilders.) Partly this is due to selection effects: we’ll tend to see houses built where land is more easily built on, and in those places land will be cheaper. If it was harder to build on it, the land would be more expensive. Nevertheless, for most new housing built in the US, land is not the major cost determinant.

This, of course, is for new homes. For existing homes, we can expect the land to be a larger fraction of the total cost of a home, if for no other reason than because the value of the physical home itself will depreciate as it ages. What do we know about the land fractions of existing homes?

At a high level, we can estimate the fraction of housing cost associated with land by using the Federal Reserve’s household balance sheet report. Per the Fed, the total value of all real estate held by households is $44.8 trillion, while the replacement cost of the structures themselves (which will include both hard and soft costs) is $27.2 trillion. This gives $17.6 trillion dollars as the value of householder land, or almost 40% of the price of all homes nationally. Though this seems high, it actually seems to be roughly the average value for the past 30 years (though historically land fractions were much lower).

We can try to calculate this another way by using American Housing Survey data. Per the 2021 AHS, the average size of a US detached single family home was about 2,200 square feet, which at then-current median construction costs would cost $293,000 to replace. Using 1.1% annual depreciation (roughly the depreciation rate used by the BEA for single family homes), and a median home age of 40 years, this gets us a median replacement value of around $188,000 for US homes. Per the Census, the median homeowner during that period valued their home around $282,000. Taking into account that homeowners systematically overvalue their homes by around 7%, this gives a median home value of around $262,000.5 This means that for the median US home, 72% of the value is from the structure itself, leaving 28% for the land. This is less than the Federal Reserve estimate of an average 40% land fraction nationally, but still higher than the roughly 20% value from new construction. So while for new housing, land is about 20-25% of the cost of a home, for existing housing this is closer to 30-40%.

But this is a national average. Land fractions will be higher, often much higher, in dense urban areas. This site from AEI gives zip code level estimates for the fraction of home prices due to land for the 100 largest metro areas in the US. We can see that for many zip codes, over 70% of the value of the house is due to the cost of the land on which it sits.

We can get a better sense of how much this matters by combining this data with zip code-level population estimates from the Census. Using this, we get that over 125 million people live in a zip code where the land share of residential property is greater than 50%, and more than 16 million people live in a place where the land share is greater than 70%.

To understand what's driving the high cost of land, we can divide the price of land into two separate buckets. The first is the “hedonic” value of the land, the value people get from being able to enjoy the space itself. The second is the “permission slip” — the right to build a certain amount of housing that comes attached to the plot of land. As we’ve noted previously, empirically people do not particularly value having additional land all that much. It’s the “permission slip” that makes up the majority of the value of most residential land parcels:

…when Ed Glaeser calculated [the hedonic value of land] for 21 metro areas in early 2000 (by analyzing home price sales and estimating how much a larger lot added to the home’s value), he found that in 16 of them, the hedonic value was less than (inflation adjusted) $1.50 per square foot, or less than $12,000 dollars for the median lot size of ~8,000 square feet…By comparison, the median new home in 2020 sold for around $330,000.

A similar study of single family homes in Boston found that the hedonic value of land for the average lot was just $11,200, compared to an average house cost of $450,000.

The permission slip, by contrast, is often incredibly valuable, especially if the permitting body limits how many of them it gives out. For instance, in the previous study Glaeser calculated the hedonic value of land for single family homes in San Francisco at $4.10 per square foot (the highest out of any metro examined), or about $10,000 for the average lot size at that time. The ‘zoning tax’ portion, by contrast (the portion of the cost due to various building and supply restrictions), was priced at around $220,000 - in other words, over 95% of the land’s value (and over half the price of the house), was due from being allowed to build on it.

Similarly, multifamily developers have told me that they will generally value land in terms of how many housing units they’re allowed to build on it. Increase the number of housing units you’re allowed to build (say, by getting it rezoned), and you greatly increase the value of the land. This is a lever developers have to work with when putting together a development deal - they might decide to take a risk and buy a cheaper piece of land that’s zoned for a relatively small number of units, in the hopes of getting permission to build more on it than is currently allowed.6

So while the price of a lot is not a particularly large fraction of the cost of new housing, it's a much larger proportion of the cost of existing housing. And in dense metro areas (the places that need housing the most), it can be even higher, exceeding 70% of the cost of a home. This high cost of land, in turn, isn’t because people value having lots of space for their kids to play on — it's because of regulatory and zoning restrictions that limit how much housing can be built on a given parcel or in a given place.

Conclusion

The cost of housing comes from a variety of sources. In most cases, for both new construction and existing housing, the largest line item is the cost of constructing the home itself. For new construction this is on average 80% of the cost of a home (including hard and soft costs), while for existing construction it's still in the neighborhood of 60-70%.

It’s only in dense urban areas that the cost of land begins to dominate the cost of new housing, driven by regulatory and zoning restrictions that limit how much housing can be built in a given area. Another way of looking at it is that in the areas that we need housing the most, zoning and regulatory factors are responsible for the lion’s share of housing costs.

Note that these are the costs paid by the home builder: subcontractors who do this work will have their own set of “soft costs” for their own overheads, administrations, profit, and so on.

Though NAHB doesn’t divide it up, “foundations” is really several distinct tasks, such as grading, excavation, and pouring concrete, which will be divided between several different contractors.

The other major source of savings for increased conditions is on “general and administrative expenses” (the costs associated with having an active jobsite at all).

This 7% adjustment comes from an Ed Glaeser paper that I’m unable to locate at the moment. can be found here (thanks Seo Sanghyeon).

Because of the way that costs are calculated, the value of land will include the effects of any supply restrictions on housing. Land costs are often assessed as a sort of residual, by taking the price of a house and subtracting the (depreciation-adjusted) cost of replacing the structure. So any sort of supply distortions that limit how many homes you can build will show up as increased land prices.

Interesting piece, thanks.

One thing that I think people sometimes have trouble with intuitively is that a "permission slip" system renders every other input meaningless when it comes to housing supply (assuming demand outstrips supply). The permission slip is the binding constraint, and nothing else matters. If you made it so that buildings were constructed with a wave of a magic wand, with no input cost, housing supply would still be a function of the number of permission slips issued each year, and the value of this technological advance would be fully captured by the people that own undeveloped/underdeveloped land + permission slips.

In practice, the other players in the game don't let the landowners capture all of the spoils from the permission slip system -- the union extracts a certain wage, the government imposes taxes (including stuff like inclusionary zoning, which functions as a tax), the consultants and lawyers impose rules so that they get a cut.

When people then do a bottom-up analysis of the cost of a home, it looks like all of the costs are really high and therefore the problem is multi-faceted, but the costs themselves are a function of the permission slip system. For example, the value of "land" (as you note, really land + permission slip) is by definition a residual calculation, the difference between the cost of building and the value of the finished asset. If you lower the cost of the other inputs, the cost of "land" will go up to fill the difference. But in real life, the other inputs are almost certainly also distorted by the process above.

We don't really encounter quota systems in the wild very much, so we never have the chance to develop very good intuitions around them. We are used to lower costs leading to lower prices to the consumer, but we don't usually consciously think about the transmission mechanism (competing firms lower prices to maintain share so that the consumer eventually captures all the benefits). The quota system disables the usual transmission mechanism.

I think this is also why people intuitively reject the idea that solving something as complex as the housing crisis is something as simple as zoning reform. But, the quota system is the bottleneck, and the *only* way to improve a system is to fix the bottleneck. That is, by definition, what a bottleneck is! It's like saying you can't fix a complicated supercomputer by simply plugging it in.

Sorry for spamming but I think there’s also a very fundamental flaw in the way that we consider land prices in this: the entire sample is biased to the point of uselessness by the selection effects of where *new* *single-family* housing is built.

If (even quite dense) SFH were being built in quantity deep within major metros that figure would be wildly different. But in addition to making in-fill development within cities very difficult, we’ve also made development of green space within existing suburbs very difficult.

So the entire sample is deeply skewed towards exurban land development, which elides the depths of the problem: not just what it costs to get houses built, but the impact on where and to what extent they *don't* get built.